We recently connected with Mehdi Dandi and have shared our conversation below.

Mehdi, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Are you happier as a creative? Do you sometimes think about what it would be like to just have a regular job? Can you talk to us about how you think through these emotions?

I am definitely happier as an artist. For me, being an artist is not just a job, it’s a way of living. It shapes how you think, how you respond to problems, and how you move through life. Making art is not separate from life; it’s part of how I understand the world and myself.

Of course, I think everyone occasionally wonders what life would look like if they had chosen a different path. I’ve had that thought too. But whenever I imagine myself in another profession, I don’t picture something ordinary, I imagine being deeply specialized, just as an artist becomes a specialist over time through experience and dedication.

The last time this thought came to me was when I was thinking about specialization itself. I imagined how interesting it might have been if my life had revolved around flying, maybe as a skydiver or an athlete whose work is closely connected to the body. There’s something beautiful about those lives too, about knowing your body and pushing its limits.

Still, I believe that joy in any profession comes from mastery and commitment. What makes art different for me is the freedom it offers. Being an artist means living with a sense of endless freedom and creativity, and I honestly can’t imagine a life richer than that. I do think about other paths sometimes, usually in moments when things don’t work out or progress feels slow, but I’ve learned that consistency and persistence are the real answers in those moments.

Mehdi, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

One of my earliest memories connected to art goes back to when I was about five or six years old. At a relative’s house, I saw a painting by Salvador Dalí, the one with the melting clocks, The Persistence of Memory. I remember asking what it was, and being told simply, “It’s a painting.” I asked why the clock looked like that, and the answer was: “Because the painter wanted it that way.”

That moment felt like a miracle to me. It was as if a door opened to another world. I realized, very early on, that an artist could imagine things differently and give new meaning to reality. That idea stayed with me.

I didn’t grow up surrounded by artists, and I didn’t really know what being an artist meant, but images always felt powerful to me. My family encouraged me to draw, and for a long time, drawing and painting were my way of understanding the world. Even though I studied mathematics formally, I eventually made a clear decision to move toward art. I began pursuing it seriously and academically in my youth, and the deeper I went, the more committed and in love, I became with it.

For many years, I focused almost entirely on painting, drawing, and occasionally sculpture. Over time, photography entered my life more seriously. My father worked with photography and video and even repaired cameras, and I was fascinated by the magic of the image, the flash, the frozen moment, the way an image is captured, printed, and then remains. That process felt almost alchemical to me.

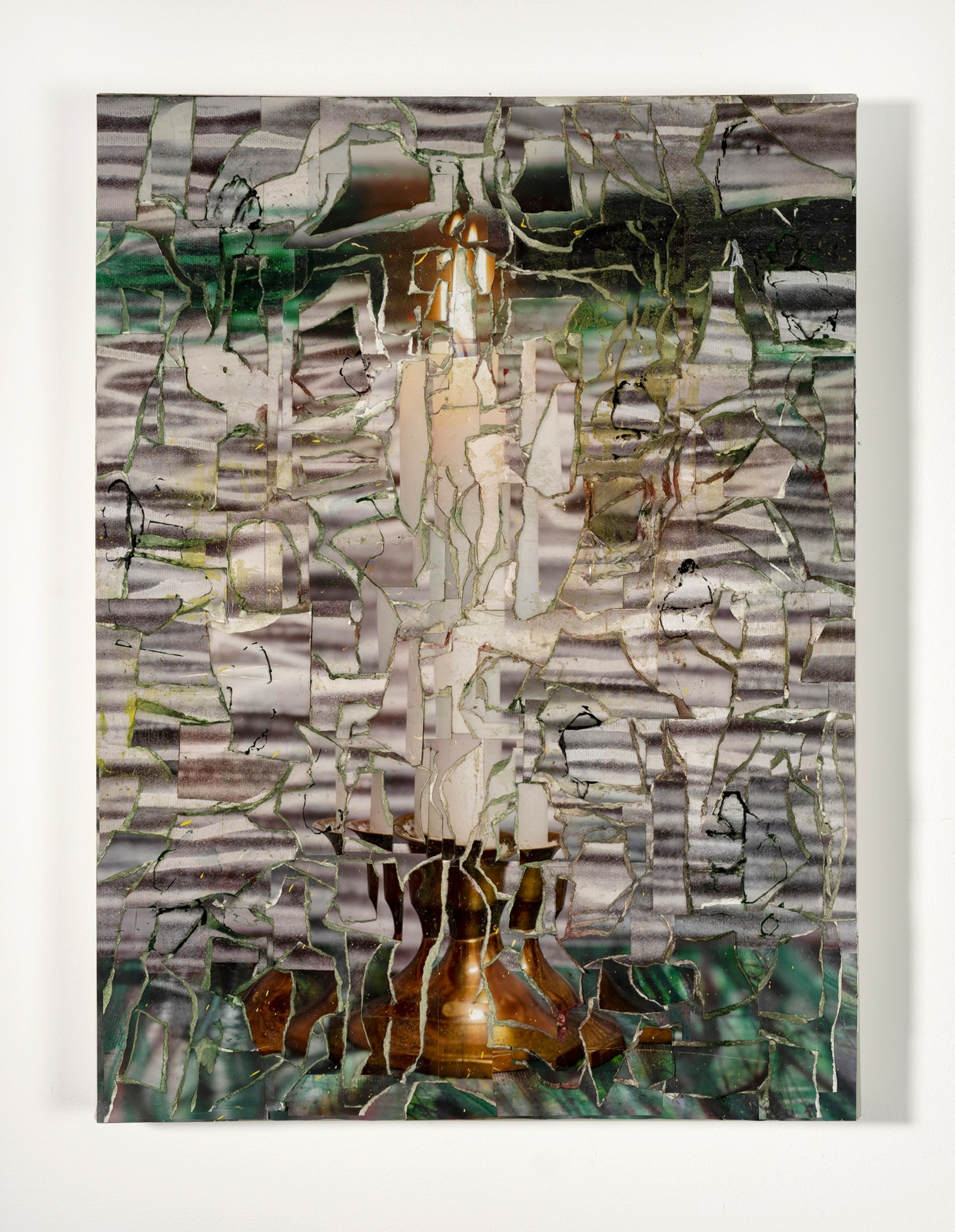

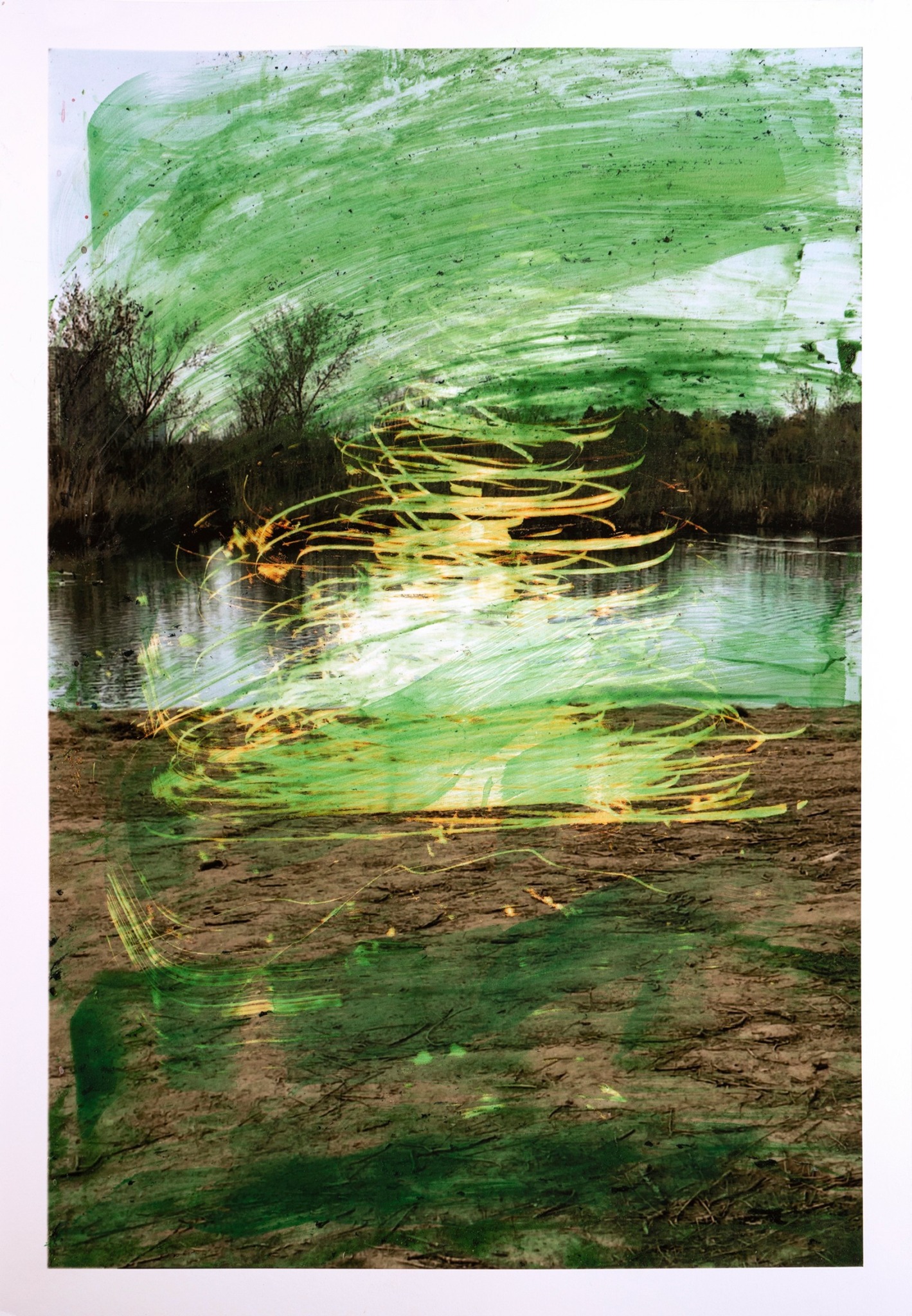

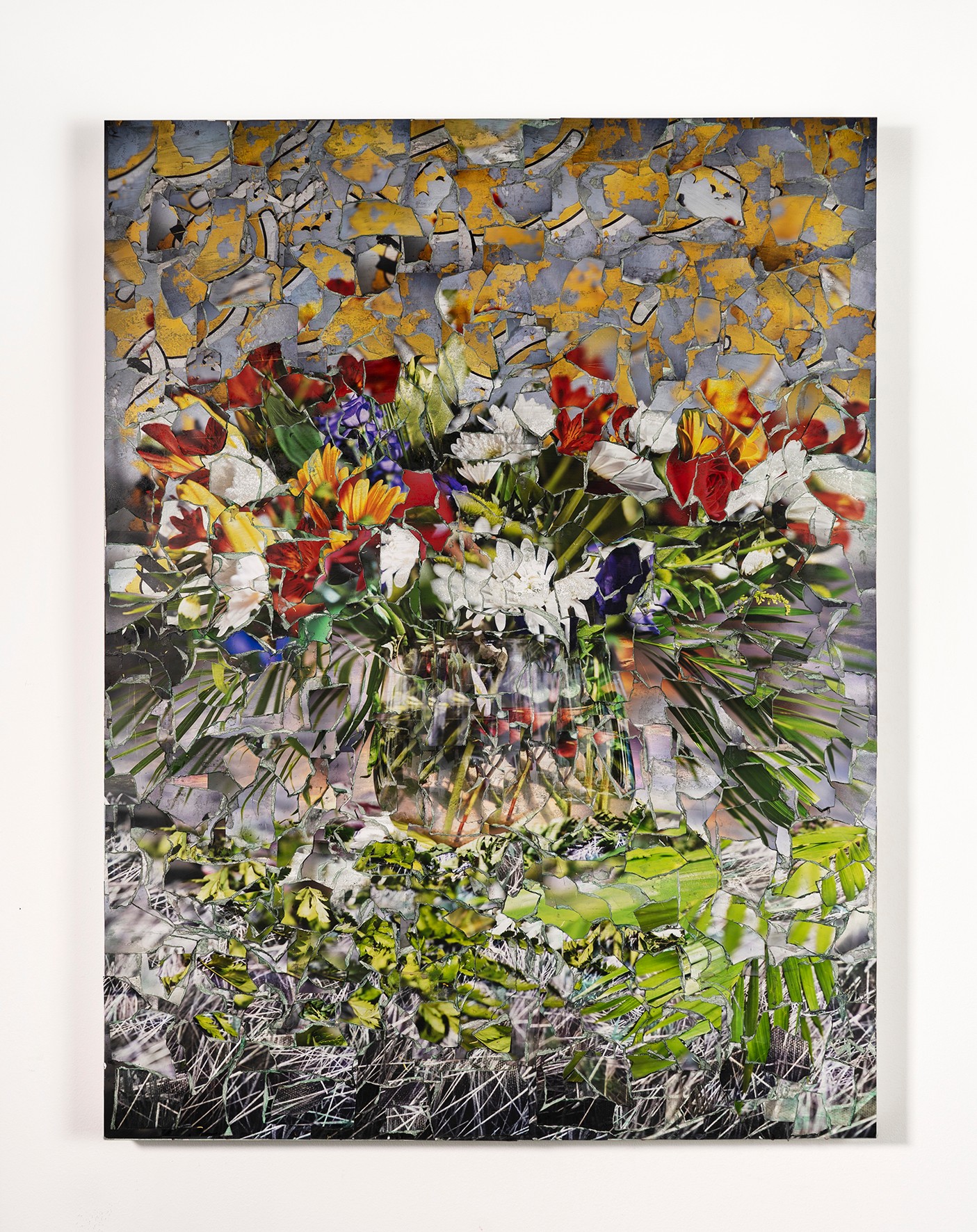

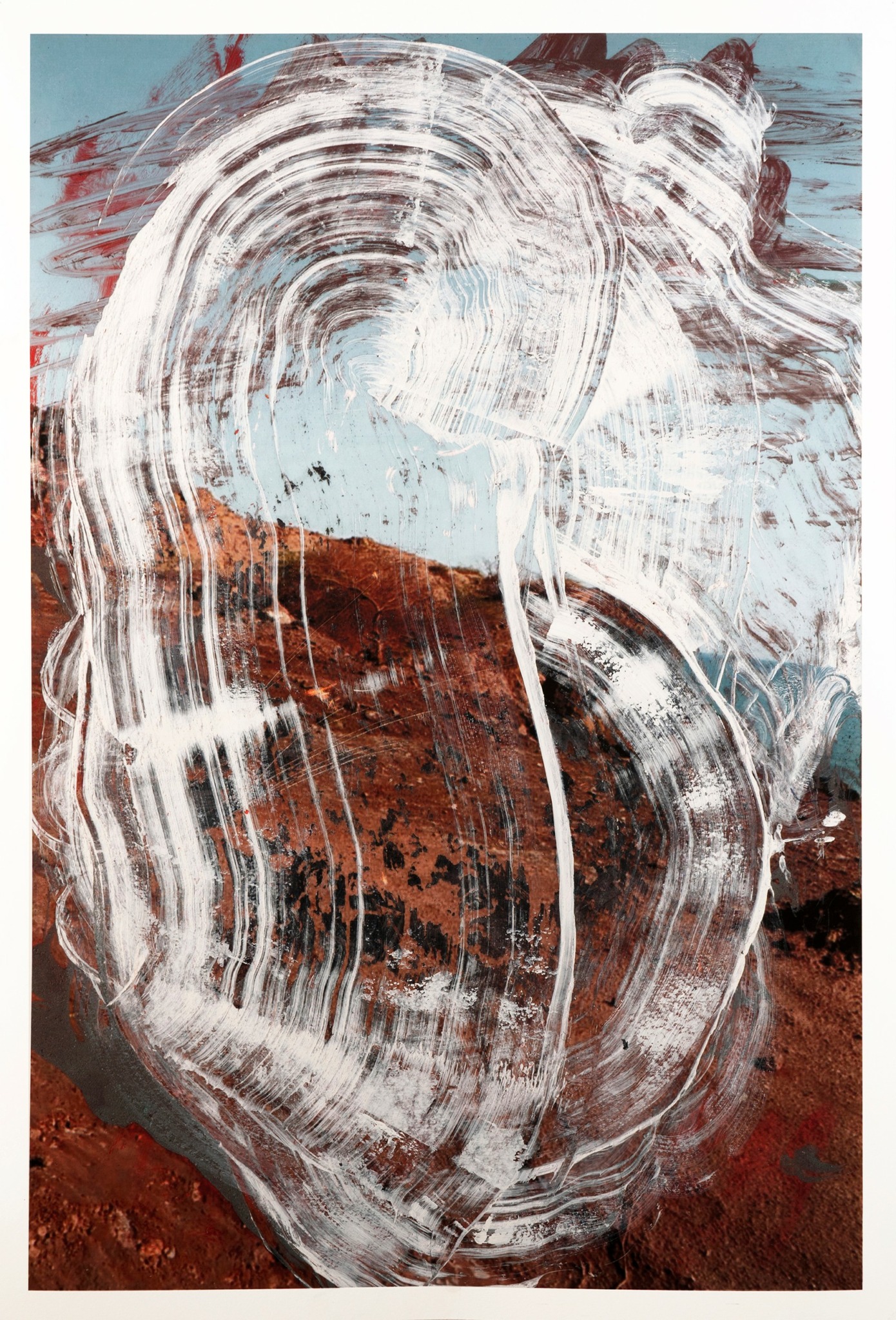

Today, my practice is lens-based, but I constantly question the image itself, its materiality, its limits, and its unexplored possibilities. I’m interested in what images can still become, and what they can reveal beyond what we already know. I try to create work that is deeply personal and unique, work that makes the invisible visible, things that are sensed, remembered, or imagined but not easily seen. In that sense, my relationship to images is close to poetry.

What I’m most proud of is developing a personal visual language over time, one that comes from years of experimentation, technique, and lived experience. Migration, in particular, gave my work a deeper meaning. In moments of displacement, art became a mental anchor for me; it kept my mind active, playful, and alive.

At its core, my work is about exploration, finding paths that haven’t been walked yet, both in art and in life. I see my practice as an ongoing attempt to add a small, honest piece to the larger history of images, and that pursuit continues to shape both how I work and how I live.

Are there any books, videos or other content that you feel have meaningfully impacted your thinking?

Yes, definitely. One of the things that has had the biggest impact on my way of thinking, both creatively and entrepreneurially, is reading and watching biographies. It’s something I do regularly, almost daily. Learning about other people’s lives, especially how they navigated uncertainty, failure, and growth, has been incredibly grounding for me.

Because I’m an artist, I naturally gravitate toward biographies of artists and filmmakers, but I’m also interested in people from other fields, writers, thinkers, or individuals who have built something meaningful in their own way. Seeing how different paths unfold has helped me understand that there is no single formula for success or fulfillment.

Two works that deeply influenced me are Alejandro Jodorowsky’s autobiographical films The Dance of Reality and Endless Poetry. Both films are incredibly inspiring, not just as films, but as reflections on creativity, persistence, and living with imagination and courage. They had a strong impact on how I think about creative life as something deeply intertwined with personal experience.

Another important book for me is Letters to a Young Artist. It reminded me that doubt, uncertainty, and struggle are not obstacles to a creative path, but often essential parts of it.

Overall, I believe that in any field, reading biographies and life stories can be extremely helpful. You begin to see how similar the challenges, disappointments, successes, and even moments of luck are across different disciplines. That realization has shaped my approach to work, management, and long-term thinking more than any traditional business book.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

I believe one of the most important things society can do is to reduce the distance between artists and the public. When that gap becomes smaller, many other forms of support naturally follow, trust, visibility, financial support, access to space, and a sense of security.

This starts with making art and artists more accessible and understandable, and by allowing artists working at deeper, more experimental levels to reach people directly. When only commercial or easily consumable art reaches the public, a large part of artistic practice remains invisible. But when more complex, thoughtful, and challenging art is given space to be seen and experienced, it has the power to shift how people think, not just about art, but about culture and life itself.

Reducing the distance between non-commercial artistic practices and the public can have a profound impact. It encourages dialogue, raises cultural awareness, and strengthens creativity across society. A thriving creative ecosystem grows when artists are not isolated, but actively connected to the communities around them.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.mehdidandi.com

- Instagram: mehdi.dandi

Image Credits

All images © Mehdi Dandi