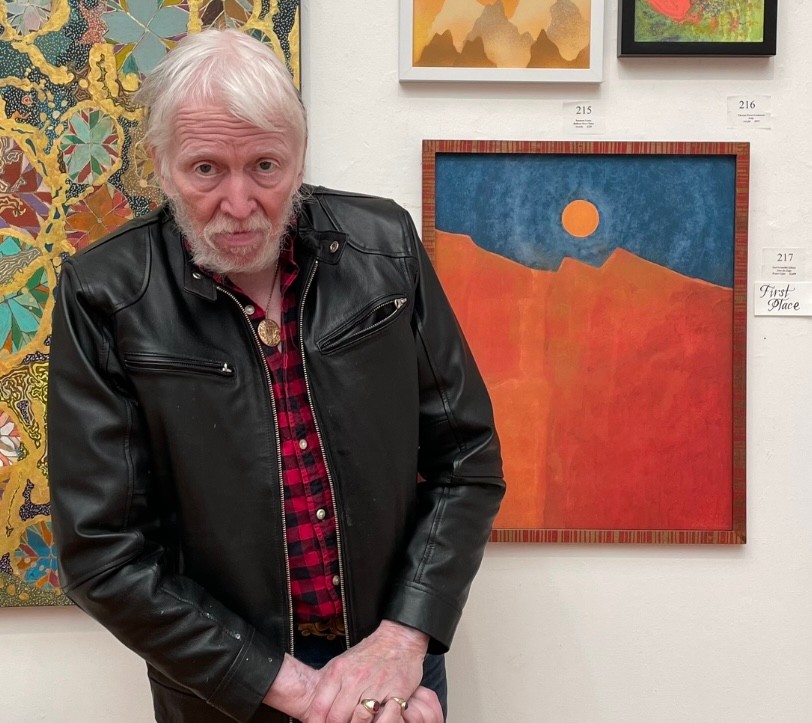

We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Earl Grenville Killeen. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Earl Grenville below.

Hi Earl Grenville, thanks for joining us today. What’s the kindest thing anyone has ever done for you?

In 1978, at the Art Students’ League, I entered the class of Will Barnet, with not much to my name but some art supplies. The one and only time Barnet spoke to me in class was to say: “It’s a pleasure to watch you paint.” Other than that, from time to time we chit-chatted, developing a social relationship. Soon Barnet was giving me introductions to the top NYC galleries, a passport that enabled me to get past the front door with its bodyguard to keep out students with their portfolios. He was also key to seeing I received an artist grant that provided much-needed funding. He nominated me, as well, into an invitational national year-long US touring exhibit. These select efforts on my behalf were more than much-appreciated compliments – Barnet’s seal of approval proved to be a life-support system, helping me to keep myself afloat, both materially and spiritually, along my creative journey. There is a saying in the art world: “You are not an artist until an artist says so.” Will Barnet’s kindness affirmed for me the privilege of being called an artist.

Earl Grenville, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

Art is what got me through a stress-filled childhood and a dislocated youth (though without any formal art training or instruction). From an early age, my most treasured possessions were the books of artworks that I pored over, figuring out – by a process I call dissecting and digesting – how colors, textures, values, and composition work, and learning how to put my understandings into practice by continually working at it and making mistakes. There’s a whole chapter about making mistakes in the book I wrote, decades later, on Acrylic Painting Techniques (North Light Publishing, 1995) – how mistakes are great teachers of what doesn’t work, of patience and perseverance and anger management (like, how many times can you throw a work-in-progress across the studio before thinking: maybe there’s a better way) –but also how mistakes can reveal themselves to be new techniques.

For example, my exasperation with frisket’s penchant for picking up and randomly depositing bits and speckles of not-quite-dry-enough paint gave way to a realization that my painting was left with a surface texture that I could not purposely create with a brush. Now I invite the frisket to do its thing. Using a small power sander in a last-ditch attempt to salvage a botched watercolor by removing overworked layers of paint, I discovered – and have come to rely on — the sander’s facility to amalgamate and burnish colors, as well as to reveal glimpses of under-layers. Another experiment in texturing involves spreading beach sand over a painting’s surface, spraying it with water, and scraping it off with a palette knife when dry. The results of these techniques share an element of potential surprise. It’s nice that making art, even after seventy, is still an adventure.

Another happy-surprise part of this adventure, especially in recent years, has been the opportunity to be connected to so many creative and supportive people, whether in venues that I can attend physically, or in the virtual meeting places online. While nothing beats seeing the actual works, and artists and viewers, in a gallery setting, I’m very much enjoying my virtual walks through online exhibits and my daily scrolls through Instagram, viewing art and exchanging comments and encouragement. These encounters are a wonderful source of involvement and inspiration.

My involvement with art includes not only creating and exhibiting, but contributing to the arts community. After service in the Navy and a few years hanging out at the Art Students’ League of New York, since settling on the Connecticut Shoreline in 1981 I became active in the then-newly-formed Shoreline Arts Alliance. In that role, I initiated the Future Choices annual juried exhibition for regional high school students, now in its fifth decade, and for several years sponsored the Best in Show award. Given that artistic expression had been my lifeline since early childhood, I felt a commitment to be supportive of young people in their creative endeavors, while also taking on commercial art projects, designing publicity materials for the Alliance, and developing my skills in a range of mediums (oil, graphite, pen-and-ink, watercolor, acrylics), as well as remodeling a home for my family.

It was during this period of involvement that I was given the opportunity to author the Acrylic Painting book. This proved to be another undertaking enlivened by surprise and adventure, inasmuch as I had, at that time, no acquaintance with the still-pretty-new-on-the-scene medium. An editor at North Light approached me, based on several articles, featuring my work in watercolor, in The Artist’s Magazine. The book would feature the acrylic paintings of twenty selected artists, in addition to mine, and would provide authoritative information on materials, techniques, tips, pitfalls, and stylistic approaches. When the editor asked if I was up to the task, I said “Sure” – and then set about giving myself a crash course in all of the above, met the deadline, and – it’s a beautiful book.

In midlife, an injury and deep personal loss set me adrift. Two decades later, I was 67 and working at treading water when a cancer diagnosis (expected to be terminal) kick-started my motor and I reached for my brushes. (“Reaching for my brushes” turned out to be a metaphor for mortgaging myself in art supplies.) In taking the plunge into what became my Totemics series of 42 watercolor paintings, I was re-visiting material I had last worked on in 1995 – and (aha! moment!) this was unfinished business. Looking back now over the eleven series I’ve done since this re-immersion, I realize that each series mirrors one stage of an inner metamorphosis (my development, evidently, requires more transformational stages than a butterfly’s); and that getting this “stuff” out on paper may not only reflect my state of being at that point, but also help me move along to as-yet-unexplored terrain.

Being a working artist again motivated me to reconnect with the Shoreline Arts Alliance, and to establish a new award for Future Choices. The annual Founder’s Award gives $500 to the teacher whose student received the Best-in-Show award; the teacher then chooses another student to share the Founder’s prize with.

This past year has been very kind to me too in terms of awards and further connections to the arts community. I’m now an elected member of the Connecticut Watercolor Society, the Lyme Art Association, and the New Haven Paint & Clay Club. I received First Place in two Rhode Island Watercolor Society exhibits, as well as a Third Place and a First Place and a People’s Choice Award at the Lyme Art Association. All of this has my head spinning. But to keep it from swelling, my mindset as an artist is to try not to take myself too seriously. I feel like the pen, not the ink, a conduit open to influences and forces beyond myself. And I like my paintings to not take themselves too seriously either, but to leave room for ambiguity and for the viewer’s varied questions, interpretations, and responses. At the same time, I believe that, to be an artist, you have to be a visionary; to be a visionary, you have to ignore other people’s versions of vision.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

RESILIENCE:

No one is born a working artist. On my quest to becoming one, I found that if you’re looking for fortune and fame (or, at the least, recognition), you find a very long and difficult journey before you. From the time you deliberately take the plunge, there are many pitfalls of dry time, whether it’s financial dearth or artist’s block or – most daunting of all – the necessary biding of time to mature in your abilities of mind (to conceptualize, to study, and to persevere, adapt, and innovate) and of body (that is, your capability to utilize the methods and materials of your chosen medium).

The endeavors of this odyssey can span decades, with you yearning all the while to actually be where you now imagine yourself – to be there, to have made it — no longer struggling to make a square peg fit into a round hole. Then, just when you think you’re in the home stretch comes the disheartening tag – the rejections from the umpires, the judges, the gallerists. It is imperative to put that negative energy into a positive perspective. You may question the source or validity of the criticism – or, better yet, examine the parameters of your abilities. Is more time to hone your talent needed? No matter the barrier, if you aren’t making it to your self-defined level ten yet, it’s important to reflect on the forward movement that you have accomplished — say, level 4 to level 5.

Part of resilience is perceiving that all next levels are to be achieved by the work you have not yet accomplished, and that those shortcomings are steps in a process toward a goal. Resilience can also entail re-envisioning the goals themselves. In the course of my seven-and-a-half decades of creative efforts and of life, I’ve managed to come to a happier re-imagining of myself. This brings my re-formed goals and me into more harmonious alignment.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

LESSONS:

Forty-something years ago, I was advised that having a respected place in the art world was contingent on representation in a prestigious gallery.

Following my dream of being an accomplished artist, I went through the doors of many noted galleries and print houses in New York, where I was unapologetically slapped in the face with one ironclad reality: If you are accepted into a given gallery’s stable, you will be considered a potential cash cow, no more or less than a hanging side of beef. Your payback will be fame and fortune — for an unpredictable period of time.

There was one such gallery in SoHo that I could only dream of showing in — until I came to see it as a potential nightmare. I was acquainted with two young artists who had links with this particular gallery. One of them had had a two-year blitz in sales before he ran out of favor with the buying public. His work had nicely profited the gallery but, as all sponges are treated after being wrung out, the artist was shown the door and, subsequently, the gutter where no one picks up “dirty seconds.” He was now a 21-year-old has-been, seated to my right in my favorite gin mill, drinking up his savings in a most remorseful manner.

The second young man and I were peering one night into the window of my dream gallery at his display of work on the back wall. I questioned him regarding my perception that all the paintings looked identical. He answered, “They are. I just move my signature around.” And, I noticed, they were all titled the same, but for the addition of a number — 1 through 70. I had seen this operation done in this gallery before. The signature on each piece was quite visible, even at this great distance, though not readable. I remarked that the display had all the qualities of the banner for “The Fantasticks.” He agreed, saying with noticeable regret, “I’ll know I’m a real artist when I don’t have to sign my work like that anymore.”

Now I found it was my turn at bat. I was still under the spell of the gallery’s cachet, and arranged to see the gallerist. I was told on the spot that my work was acceptable, providing I renounce my current medium of watercolor in favor of oil, and paint larger-than-life. My subjects and style were just fine, as long as I was willing to throw myself on the sword of the gallery’s dictates. I wasn’t.

I fared no better with two international print houses. One said, “This image (a barn) is great. Just bring me 70 print editions of barns.” (I guess the expectation was that money was already no object for me, or that I would gladly plunge myself into debt.)

Next, before approaching a gallery with a formidable-looking bodyguard, coupled with what appeared to be bullet proof glass, I decided to do some research. Word was that this gallerist never paid any of his artists. I consulted with my friend Will Barnet, a well-established artist who had given me the introduction to this gallery. Was it true that the artists there weren’t paid? ”Yes,” Barnet said, “but he’ll make you internationally famous, then you’ll make your money.” I didn’t sign up.

That was almost fifty years ago and I’m fine with the ending of my story. Young as I was then, I followed my own heart and mind, and I’ll admit it’s taken me some time to put to rest any misgivings or second-guessing. I might have saved myself a lot of time and frustration if I had given more thought to examining and questioning the destination on my map of dreams. The decades since then have led me to appreciate that the route, the steps in the journey, are the essence of the search. And I can confirm, to the youth I was, that being comfortable with yourself, rather than rich and famous by means of someone else’s will, is a far more gratifying place to arrive at.

Contact Info:

- Website: earlgrenvillekilleenart.com

- Instagram: egkwatercolorist

1 Comment

Anon from Conn

A very real pleasure to reconnect with Earl in this way. A pleasure not only to find him doing well but to revisit his art. I have paintings of his in three rooms in my house.