We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Chris Lascelle. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Chris below.

Chris, appreciate you joining us today. We’d love to hear about one of the craziest things you’ve experienced in your journey so far.

Let me set the stage: Millions of viewers were ready to tune into Barack Obama’s presidential address to the Canadian Parliament, a live broadcast that almost ended up being completely silent because of a single broken cable. I was the lead broadcast engineer, and it was my job to fix it.

One thing the average viewer doesn’t realize about live television is the amount of planning that takes place before the show. A typical daily newscast uses a timing formula that is years in the making, and the crew runs mostly from muscle memory. Broadcasting a hockey game is a carefully choreographed dance of hooking up cameras and equipment, connecting broadcast trucks to facilities, running through all of the pre-game setup, and making the show happen. Some events are less repetitive, for example: an award show of major sports championships. These can take well over a year to plan.

A major presidential visit is planned months in advance and watched by millions. Political broadcasts have additional complexities due to safety and security, information privacy, physical logistics, the number of organizations involved, even the age of the buildings where political stuff typically happens is a challenge. I was the lead engineer in charge of signal distribution from equipment installed in parliament, sending video and audio signals to some local networks, a national press team who was operating out of a broadcast truck, and some US organizations. The feed going to the world was being passed through a broadcast truck to all of the other major news outlets in the world to be broadcast live on BBC, Al Jazeera, CBC, CNN, etc. We had set up a fiber optic cable to carry all of the microphone audio. As a backup to this fiber optic cable, the team ran a copper cable carrying the same audio. After weeks of meetings explaining and confirming the plan, and at least a full day of testing the “primary and backup” feeds into the truck, we discovered the biggest communication failure of all: the broadcast truck team had no idea about our primary fiber-optic audio feed. It was running from our equipment, through a dark basement, and sitting unplugged at their end.

How we found out was a frantic call over the intercom: “we’ve lost audio.” A sentence that will suck the air out of your lungs for those in this business. Only by some mysterious force did this not happen during the actual show, but with minutes’ notice and the motorcade on its way from the airport, the pressure was definitely on. We called back to the truck over the intercom, yelling some technical jargon: “switch over to the backup feed, embedded audio pairs 1 and 2 on SDI on patch J22 running to you via the service panel in the press gallery.” A few long, heart-stopping seconds later the response came: “That’s our main audio feed, where is the backup?” My heart sank. “The main is the fiber going to your rattler, cross-patched in the basement.” “We don’t know about any fiber.” What the f#*k? This is when it set in that the biggest international news event of that day, possibly that week, was going to be silent if we weren’t able to fix a cable that mysteriously snakes its way through the 100-year-old stone walls of the gothic Canadian parliament buildings.

All of the meetings, planning, and communication in the world is no replacement for first-hand confirmation.

My team immediately started following cables around the floors, up staircases, into crawl spaces, and eventually found a weak point: a connection plate screwed into a wood-paneled wall in the press gallery. “Open it up” was said and we all fumbled for screwdrivers and removed the panel from the wall to reveal a broken connector. Most panel-mount coax connectors made after 2004 are crimped onto the cable with a compression tool. This one was older and soldered, and the solder joint was broken. There was no time to look for a vintage and obscure connector and tool. I decided that we needed to re-solder the connector as though we were still in the 90s. With those words, I sprinted away—scattering down stone-stepped staircases in search of a portable butane soldering iron, solder, wire cutters, and a box cutter knife to peel off the outer jacket of the wire. All of these items had to make it back upstairs, past the secret service metal detectors, to quickly complete the repair. This is where a decade of exploring the strange century-old gothic corridors in between levels that snake into back rooms and hidden offices may have saved my career.

I made it back up to the press gallery and handed the soldering iron to a seasoned technician—more than qualified for the job. He couldn’t stop his hands from shaking. He said he couldn’t do it. I looked down at my hands and they were still. I took the soldering iron and repaired the cable. The resulting unplanned gathering of technicians and onlookers got the attention of the Secret Service. When an agent came over to see what was happening, I told him, “if anyone touches that cable, the show is over.” He understood the severity of that statement and assigned a guard dedicated to this one connector, removed seating from the immediate area, and brought in stanchions to establish a perimeter. We heard from the broadcast truck that audio was back just as the president of the United States showed up at the front steps. I spent the next two hours staring at the audio meters of a TV monitor as though the rest of the world didn’t exist. When the show was over and everything went well, there was no flashy show of thanks, no celebration. Just a silent nod from a few who had been in the same trenches, a shared understanding that this is what live broadcasters do: we make it work, no matter what.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

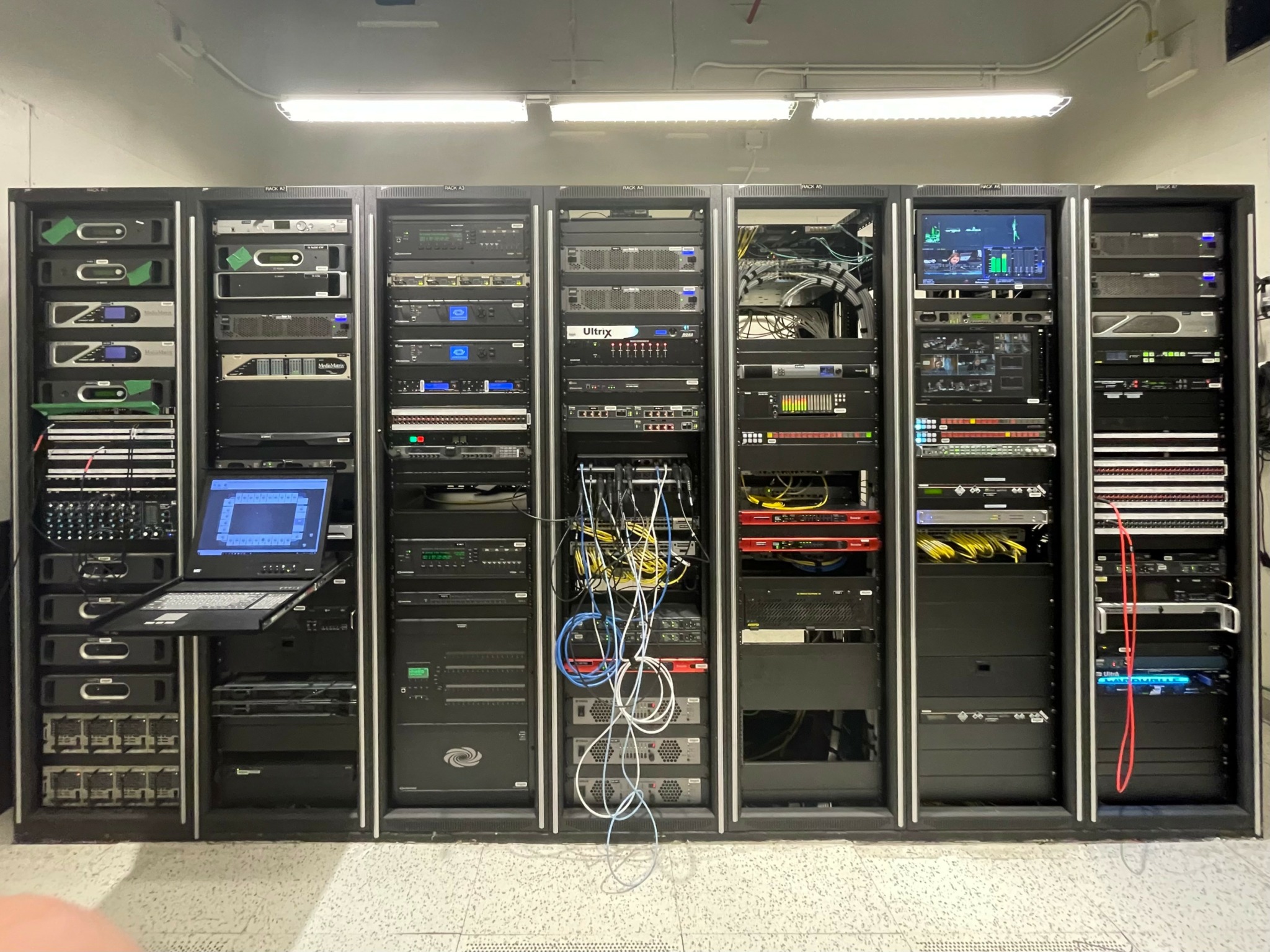

I work in the field of AV design and broadcast engineering, but I often think of my work as making functional art using wires and equipment. The list of things I can design includes: livestream systems, auditoriums, theaters, conference rooms, video installations, and more. What I really do is provide the service of translating a client’s concept for a human experience into a technology based delivery system that will create that experience. The technology is a bridge between the idea and the outcome, and my role is to understand how the technology works so that the client can focus on the idea.

My life includes decades of painting and making visual art, and a lot of my paintings explored the push and pull of negative space and how to guide the eye of the viewer. There are so many parallels between making balanced and cohesive art and designing elegant and reliable systems, that this technical field of system engineering very much feels like art, and that is how I approach it.

Some of the projects that I’ve worked on include systems in: Shibuya stream (Tokyo), St. Johns Terminal (NYC), King’s Cross (London), Anulfpost (Munich), 65 King (Toronto), Parliament of Canada (Ottawa)

What do you think helped you build your reputation within your market?

While a lot of my success feels like good luck, my reputation is really built on an obsession with controlling the things that are within my power. I’m very passionate about my field and I’ve made some good decisions, but in AV design, audio engineering, and livestreams, a career can hinge on successful outcomes when so many variables are outside of your control.

The best you can do is plan for every foreseeable failure, know that there are unknown unknowns, test early, test deeply, and hope to eventually have enough success saved up that it shields your reputation against the occasional scrape and bruise.

This “big picture” perspective is what helps me make critical decisions. It often means asking for things that other stakeholders didn’t expect, like an extra week for testing or a backup generator. It means I’m often the one saying, “No, we can’t do that over WiFi,” or “No, an action camera from a department store won’t work for that shot.” My reputation isn’t just about making things work; it’s about relentlessly preparing for failure so that when a piece of bad luck hits, my clients are shielded from it.

How do you keep your team’s morale high?

I’ve found that the best path to high morale is about creating an environment where a team can find personal fulfillment. This happens when they are given the autonomy to tackle challenges that are just out of their reach, fully commit, and ultimately get to own the results and be recognized for them. This sense of challenge and ownership is key.

A Good Manager is a Shield

Essentially, a good manager doesn’t manage work; they manage the environment. They protect their team from things that block their work, like bureaucracy, pointless meetings, and political noise. This frees up the staff to focus on the work they were hired to do, without constantly worrying about distractions.

The Team is the Most Important Factor

A manager’s most critical responsibility is to protect the team’s culture. This can even mean quickly addressing or removing individuals who consistently bring down morale with a bad attitude, poor work ethic, or nagging complaints. A healthy, positive team dynamic will keep morale high and work output strong.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.kilammedia.ca/145-productions

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/chris-lascelle

- Other: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm17113825/