Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Yulia Spiridonova. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Hi Yulia, thanks for joining us today. We’d love to hear about when you first realized that you wanted to pursue a creative path professionally.

I grew up during the Perestroika era in post-Soviet Russia, in a small town called Kolomna, about two hours from Moscow, in a family of engineers and intellectuals. My grandfather’s Zenit—a Russian point-and-shoot camera—was a constant presence. I began photographing at the age of nine, and taking pictures during vacations and summer camps quickly became my greatest excitement. I remember arguing with my mom about why I needed more than three rolls of 35mm film—what, after all, was I so eager to photograph?

Looking back, those early images were mostly ordinary: family portraits, landscapes, school trips, self-portraits. But the medium captivated me. There was something about photography’s capacity to hold memory—imperfectly and unpredictably—that felt magical. A frame might come out entirely different from what I imagined, or a roll of film might be ruined in processing, and that thrill of chance stayed with me. By the time I began my undergraduate studies, I was deeply committed, experimenting with cameras and formats, and dreaming of photography as a profession.

One pivotal moment came when I attended the opening of Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s exhibition at the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow (MAMM). His staged photographs—and the debates they sparked around photographic authenticity, artifice, and memory—had a profound impact on my thinking. It was the first time I fully understood that photography could be something constructed, not just captured; that it could reflect internal states as much as it documented external reality.

The following year, I had the opportunity to audit classes at the Yale School of Art, studying medium- and large-format film photography with Lisa Kereszi and John Lehr. I also attended graduate critiques, immersing myself in a rigorous artistic community that fundamentally shaped my understanding of contemporary photographic practice.

Yulia, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

My decade-long work as a senior photo editor and art director at one of Russia’s leading media companies—reviewing thousands of images daily—sharpened my critical eye and exposed me to the complexity of photographic meaning. That experience deepened my interest in questions of authorship, copyright, and re-appropriation, and how visual material can be used to construct or destabilize narratives. This led me to embrace collage as a core method in my artistic practice—a way of fragmenting, layering, and reassembling images to open up new interpretive space.

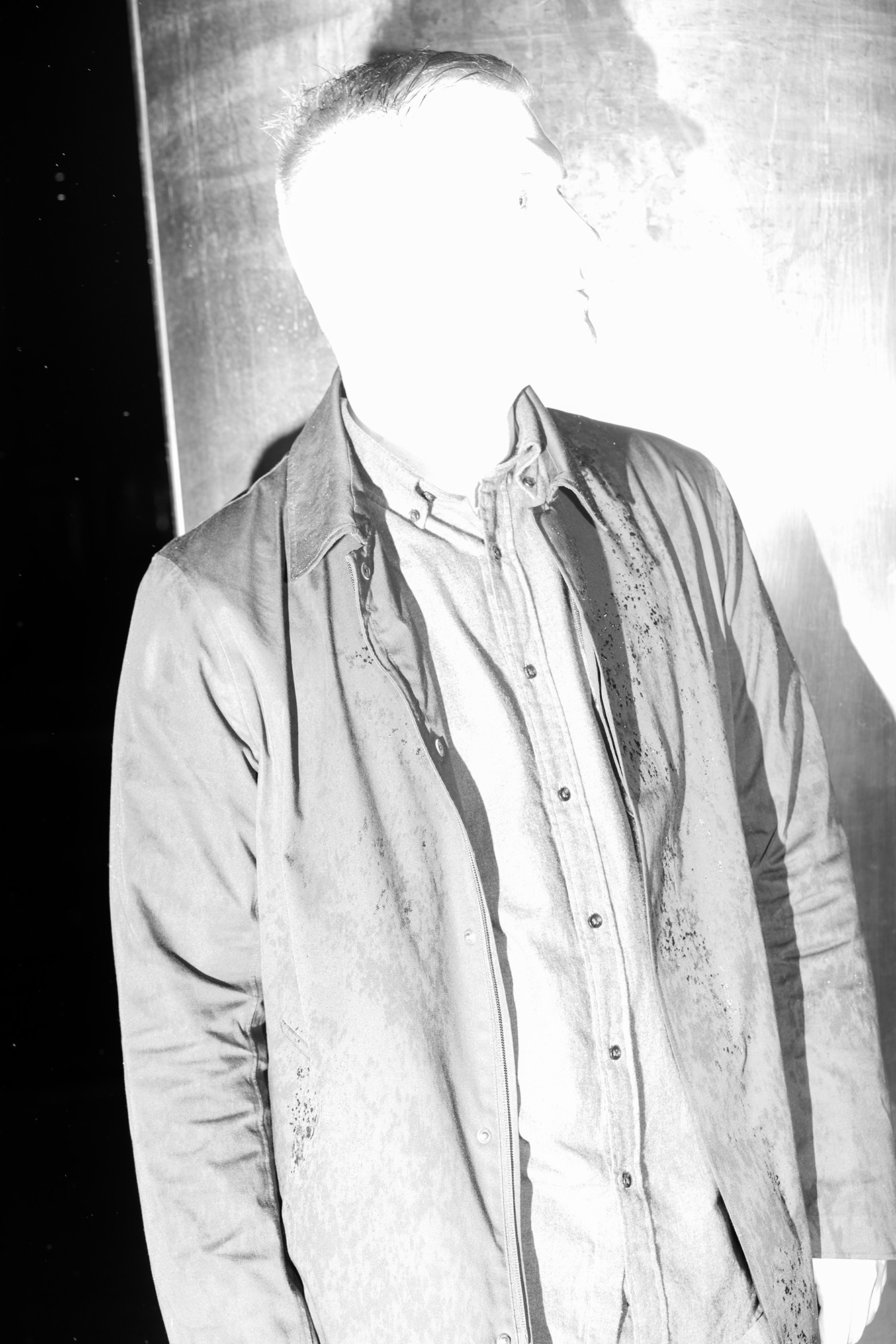

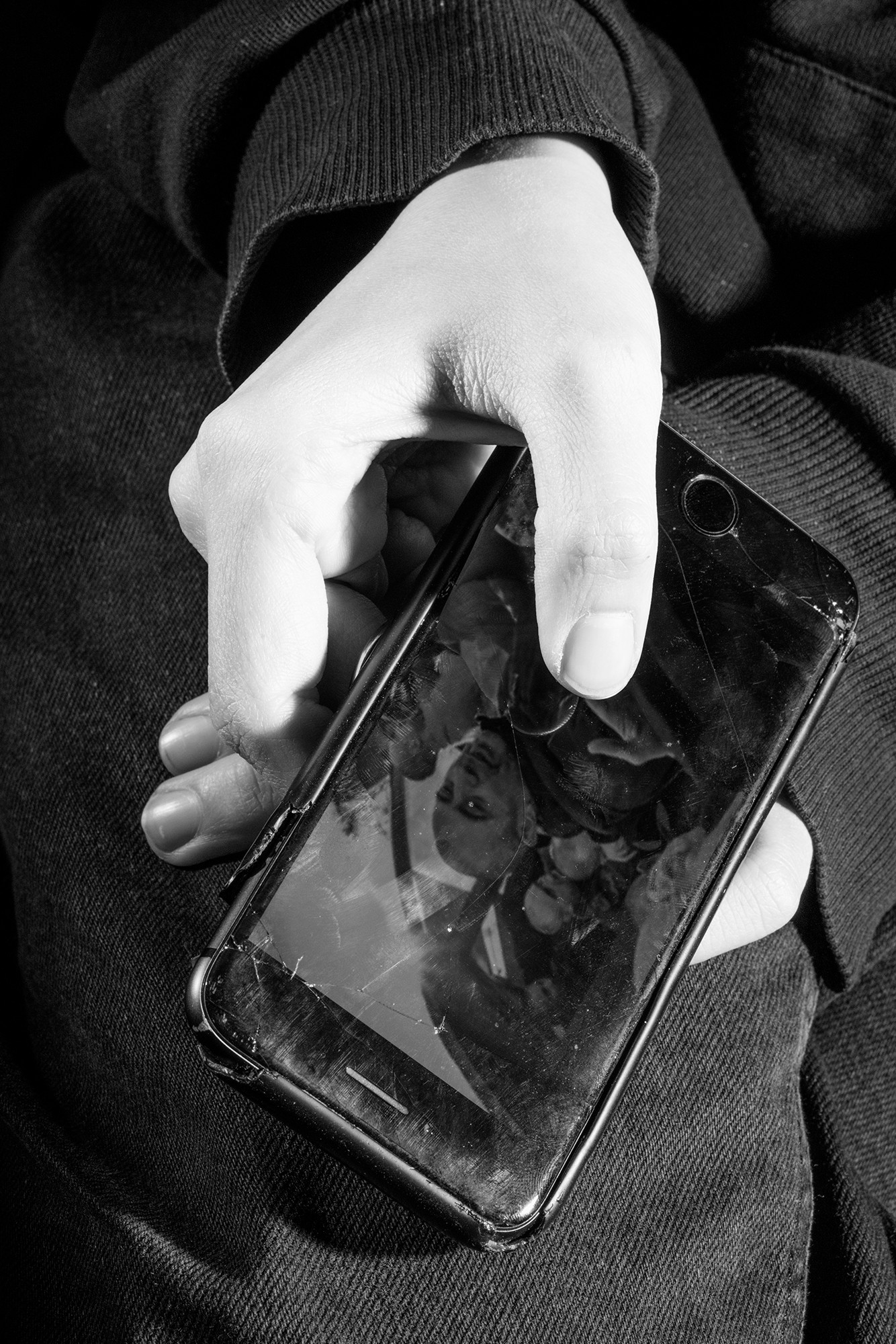

This trajectory continues in my most recent project, “Unseen Presence: Homeland Hues”, which follows members of the Russian-speaking diaspora in Boston—Russians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Armenians, Georgians—many of whom have left authoritarian or semi-authoritarian regimes. The project marks a return to the singular photographic image while exploring how contemporary portraiture might evolve in an age of total surveillance and algorithmic facial recognition. It’s an attempt to consider photography’s role not only in representation, but in resistance—against invisibility, against misidentification, and against systems of power that flatten lived experience.

Is there mission driving your creative journey?

What continues to compel my practice is the transformative force of contemporary art—its capacity to unsettle assumptions, reconfigure inherited constructs around identity, equity, and belonging, and to evoke a sense of solidarity. It is this generative, connective potential that keeps me tethered to making.

In my ongoing work with the Russian-speaking diaspora in Boston, what resonates most deeply is a quiet yet profound cohesion among Slavic communities. I photograph Russians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Armenians, and Georgians—many of whom have absconded from authoritarian or semi-authoritarian states in pursuit of a more livable life. Displaced by regimes that rendered daily existence untenable, they carry the psychic weight of exile and, at the same time, a lucid understanding that the culpability for conflict lies not with people but with power. Despite disparate national identities and lived experiences, they assemble around shared values—resilience, mutual recognition, and a persistent belief in human dignity.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

One experience that tested and revealed my resilience was the moment I had to leave Russia at the onset of the war in Ukraine. After more than a decade immersed in visual media—as a senior photo editor and art director—I found myself abruptly untethered from my professional infrastructure, my language, and my community. The frameworks I had worked within collapsed overnight under the weight of censorship, fear, and political erasure.

What followed wasn’t a grand reinvention, but a slow and deliberate reorientation. I turned to photography not as documentation but as a connective act. In Boston, where I resettled, I began meeting others who had also crossed borders, both literal and psychic. That constellation of voices and experiences became the foundation for Unseen Presence: Homeland Hues, a body of work that traces the fragmented but resilient existence of Russian-speaking immigrants and exiles.

Resilience, in this context, emerged not from endurance alone, but from the willingness to begin again with attention and humility—to build a practice not despite dislocation, but because of it.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://yuliaspiridonova.com/home

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/yuliadspiridonova/

- Linkedin: https://www.instagram.com/liver_lovers/

Image Credits

COURTESY OF THE ARTIST