We caught up with the brilliant and insightful X. Ho Yen a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

X., thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Can you tell us about a time that your work has been misunderstood? Why do you think it happened and did any interesting insights emerge from the experience?

This question is phrased from the standpoint of a single occurrence, but I’d like to talk about something recurring. It’s important. Hollywood has trained everyone to think “science fiction” means derivative trash that’s about juvenile stories of alien invasions, men with guns/violence porn, time travel, space opera and other such material that’s driven by technological or scientific contrivances amenable to flashy visual effects but without cultural challenge.

I have known people who say, “I don’t like science fiction” and then go on to watch “Firefly” and love it. Then they say, “but that’s not science fiction”.

“Firefly” takes place hundreds of years in the future in another star system. The core setting is on a spaceship.

The conviction to declare “Firefly” as not science fiction reveals just how deeply the Hollywood idea of science fiction has become embedded in our culture.

Something else that reveals this: Amazon’s subcategories of science fiction. For starters, it comes bundled under the top-level category “Science Fiction & Fantasy”. Much has been written on the fundamental difference between science fiction and fantasy, but the same history that led to the Hollywoodization of science fiction has also led to them being bundled together. Star Wars had a lot to do with that. Star Wars is fantasy that happens to have a futuristic setting.

Your choices under the SF&F combined category are: Speculative Fiction, Space, Hard Science Fiction, Fantasy, Space Opera, Aliens, Space Fleet, Alien Invasion, First Contact, Epic, Colonization, Sword & Sorcery, Witches & Wizards, Magical Realism, Cyberpunk, and Outer Space.

There are no categories like “Literary”, “Subversive”, “Thought-provoking”, or even “Near Future”, categories which imply a more direct applicability to our current world and struggles. You might think “Speculative Fiction” would carry that implication, but it’s the opposite. Speculative Fiction is the catch-all for all fiction that specifically focuses on *departures* from our reality, and it includes things like superhero stories. Superhero stories often have brilliant, important storylines, but sometimes they’re just about gods fighting gods. And not everyone needs or likes that level of departure from reality.

You might think that “hard science fiction” is a more “pure” category for “real” science fiction. But the history of science fiction has resulted in “hard science fiction” being a catch-all for military science fiction, war stories with a futuristic setting. Men with guns in space. It wasn’t always like that, but the great popularity of the excellent novel “The Forever War” by Joe Haldeman propelled that category into existence. Derivative works focused on war, with less challenge.

I write realism-based science fiction that’s about topics important to our current world and struggles. Yes, I use writing devices, but the stories are not about those, they merely use those to set up the big questions and explorations of humanity.

Is my work misunderstood? Yep. Because I’m a white-looking male who writes realism-based sci fi, it’s all too often assumed that I write military sci fi or space opera. Is my work mischaracterized? By dint of the only categories available to me on the vendor sites, yes, my work de facto is mischaracterized. There are no appropriate categories. Many people don’t even believe that “literary science fiction” is possible!

Why is this important? Aside from being important to me, it’s important because the high-volume internet commercialization of books, using these provided categories, perpetuates the Hollywoodized idea about what science fiction really is. How is someone like me to reach my audience if the audience “doesn’t like science fiction” (using Hollywood and Amazon’s definitions) and can’t find “Literary” or even “Near Future” science fiction if they even knew that they wanted to find it? The point is, the situation we’re in does the *audience* a disservice. I’m just one person affected by this on the supply side of the equation. But far more people will fail to find good science fiction because of these biases that are built into the system.

Why is that important? Because good science fiction changes lives for the better and changes the world for the better. You and I have been influenced and affected by good science fiction without even realizing it. Whole books are written on that topic, and I’ll merely gloss over it here. But go back and remember the early works that expanded minds like nothing else can. H.G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds” was only on the surface an alien invasion story — more importantly, it expanded the mind by bringing up the topic of the unseen world of microbes, which take down the Martians. Not us, not our military might. Microbes. Jules Verne’s “The Time Machine” was not time travel contrivance for some kind of dramatic battles across time. It expanded our minds beyond our own lifetimes, it examined how humanity could possibly evolve, and why, and revealed why it’s folly to think of us as some kind of evolutionary perfection. Isaac Asimov’s books about robots and psychohistory have had a profound effect on our world. I’ve written substacks on this topic, and many others have written similar things. To deny the world good science fiction in favor of merely flashy, pulpy science fiction that’s more easily categorized in synch with Hollywood is a tragedy.

So that’s my answer about being misunderstood and mischaracterized. I write science fiction, but it’s not what you think.

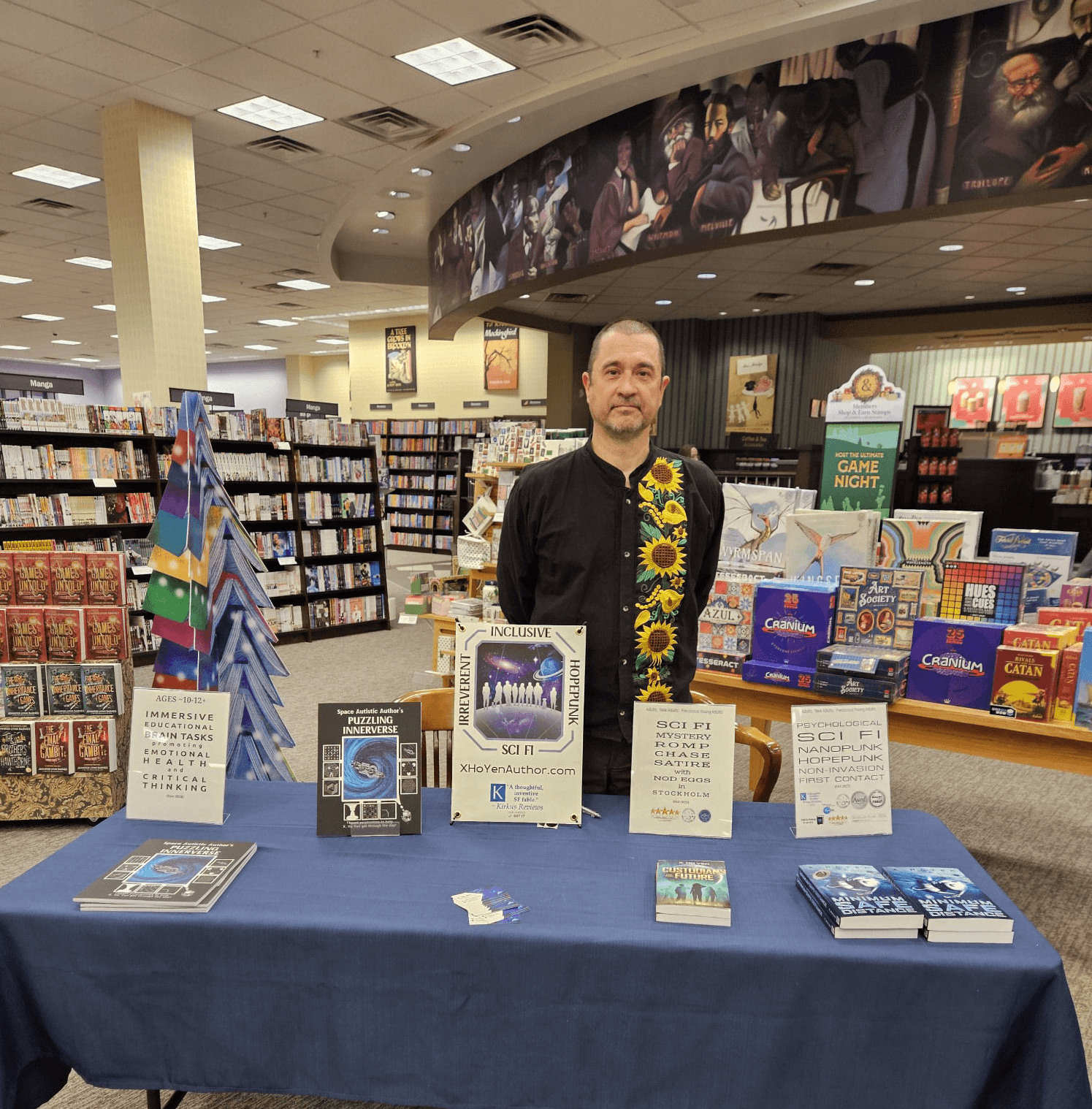

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

X. Ho Yen is the pen name of a Chinese-Cuban-East Prussian child of refugee immigrants. When his Cantonese grandfather immigrated (as a contract laborer) to Cuba, his Chinese name was interpreted as “Ho Yen” and spelled as “Hogen” (a ‘y’ sound is spelled with a ‘g’ in Spanish). This pen name is not cultural appropriation. It’s roots. The effects of unrecognized autism (late 1900s) and a broken family dominated X.’s life for 42 years. With rare help and sheer luck, including a mutually supportive marriage, he survived. He broke a lifelong Complex PTSD in 2007 and somehow managed to get an education and a career, although very late, as usual.

Before his 3 decades in aerospace engineering, he was a sandwich maker, security guard, deliverer of flowers, preschool teacher, data processing grunt, taxi driver, and independent software author.

X. is a feminist. Women’s rights are human rights. It should come as no surprise that X. sees one race, the human race. Living in a tiny margin himself, X. is an ally of the marginalized.

He wants to continue the trend of humanizing and de-militarizing realism-based sci fi, and does not write stories with white, male, American main characters.

He is a big fan of Carl Sagan and Jacques-Yves Cousteau, great explorers and science communicators of the 20th century.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

This is related to the earlier topic on the Hollywoodization of genre fiction. Everyone’s creative in some ways, but here by “non-creatives” I assume we mean folks whose major activities in life aren’t centered around their creative activites.

I think now that so many indie writers are out there cranking out Hollywoodized genre fiction in a quantity over quality way, it’s all too easy for readers and potential readers to see indie writers as “used car salesmen stereotypes”. I mean, a lot of writers are exactly like that. One scan will show just how many hypersexualized females are depicted on book covers, almost always *white* females by the way. I wrote a substack on representation in my writing in which I show what I perceive as a generic indie sci fi book cover these days. It has the aforementioned white, hypersexualized female straddling a flying rat in the midst of a space battle, shooting her own ray gun. That’s the sort of thing *I* kept seeing on the covers of newly announced genre books.

Such works just scream “used car salesman stereotype” to me — smooth-talking and titillating the prospective customer into an impulse buy, only to find that the car is underpowered, susceptible to rusting, and won’t last long.

I’m concerned that the audience believes that all writers, especially indie writers, are merely hawking impulse buys that will lead to buyer’s remorse. That the audience now approaches every new book in a guarded way, just as you would when approaching a salesman you think might try to dazzle you with smooth talk and distraction.

Not every indie writer is out there cranking out derivative trash. Or at least not cynically, seeing it as a side hustle. There are those cynical hustler types out there, cranking out many books a year (sometimes now using AI to accomplish that). We used to call low reliability, cheap cars “econoboxes”. I do believe there are many writers out there cranking out the book equivalents of econoboxes. Econoboxes get people around, but they’re not what you call evergreen.

I just want everyone to know that it’s not universal. Plenty of us are writing from the heart, and a number of us take the craft seriously and have learned to write well, at least as well as some of the books you’ll find on the NYT bestsellers list (which really just tracks virality, not quality — I recently read two books by indie authors not even writing in my genre, and I thought they were superior to a couple of NYT bestsellers I read). I think these points are probably more easily understood by creatives, which is why I bring this up in the context of communicating to non-creatives, many of whom are my potential audience.

Many readers *want* hypersexualized white females riding flying rats and shooting their ray guns in space battles. I can’t deny that. But at the risk of sounding elitist, for those who want a deeper, potentially transformative experience, look for the book covers that don’t have a pretty female. Look for the back cover blurbs that don’t merely describe *events* but get at some mature emotional or psychological content. Visit author websites, which will tend to reveal what they focus on. Look for book awards that have a literary bent. (There are plenty that are quite happy to focus on pulp.) Don’t just rely on Amazon’s categories. And, I dare say, look at books that aren’t coming out once a year or faster. Consider standalone books rather than series. (Series tend to be more about creating a world and then living in it over and over again. That’s all well and good, but consider this — how many books do you really want or need set in Tolkien’s Middle Earth, just to keep living there?) Escapism has its purpose, but there’s now an infinite supply of streaming worlds you can escape into, if available. Books that aren’t just about escaping into another world can do what no tv marathon can do. I’ve seen one, maybe two examples of deeply transformative ‘movie’ experiences. But I’m routinely transformed by substantive books, ones that aren’t merely about escapism. If/when you want more than the flying rat thing, or if streaming is outside your budget, this is how you find it. And good science fiction, in particular, can be truly mind-expanding.

More to the substance of the question, for me writing is one of my only ways of reaching out. As an autistic, there are things about my in-person communication style that just don’t work for people, especially after I begin to feel comfortable with someone and relax some of my “social emulator” guard rails. But I can write stories that don’t have that problem.

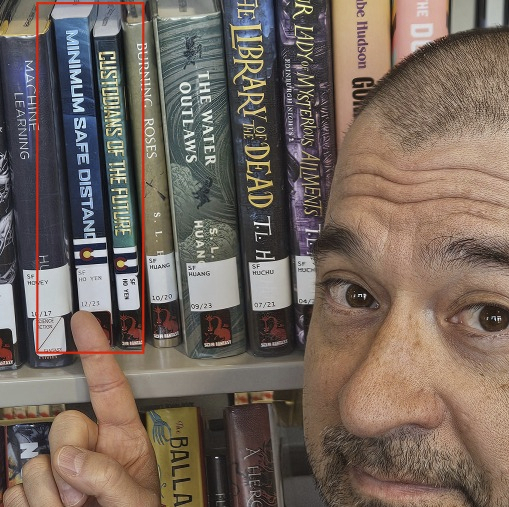

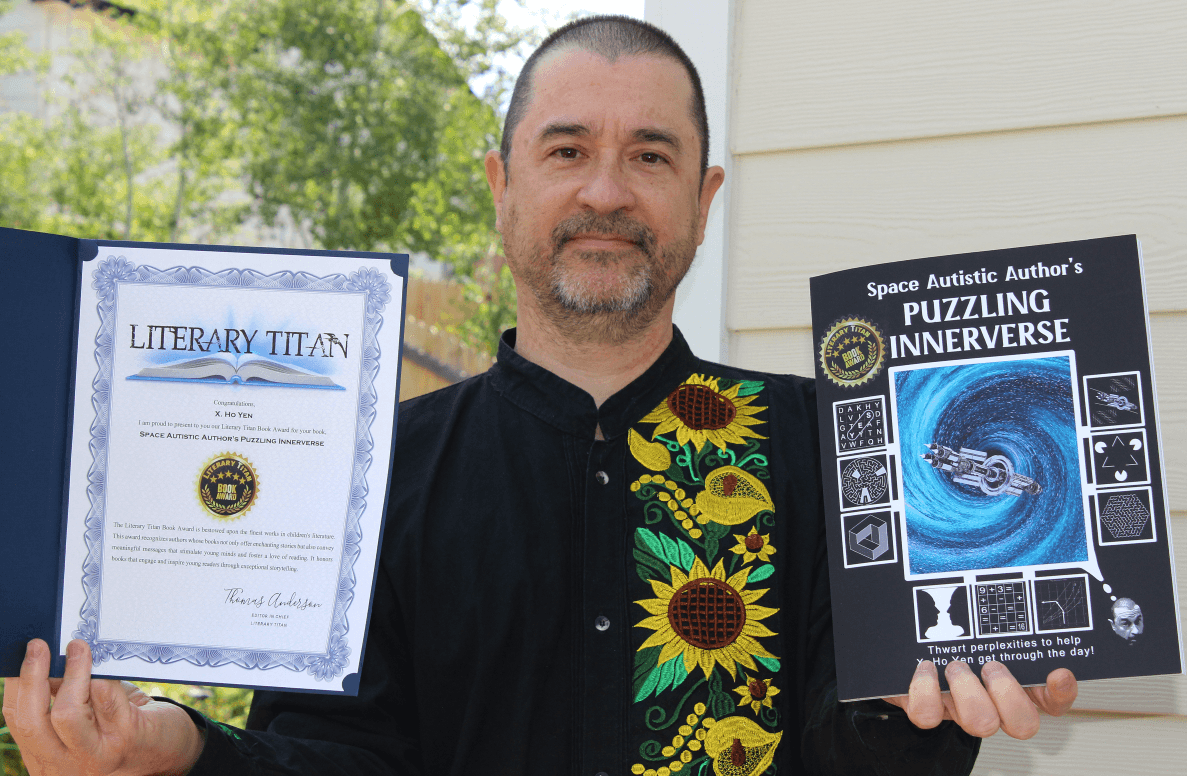

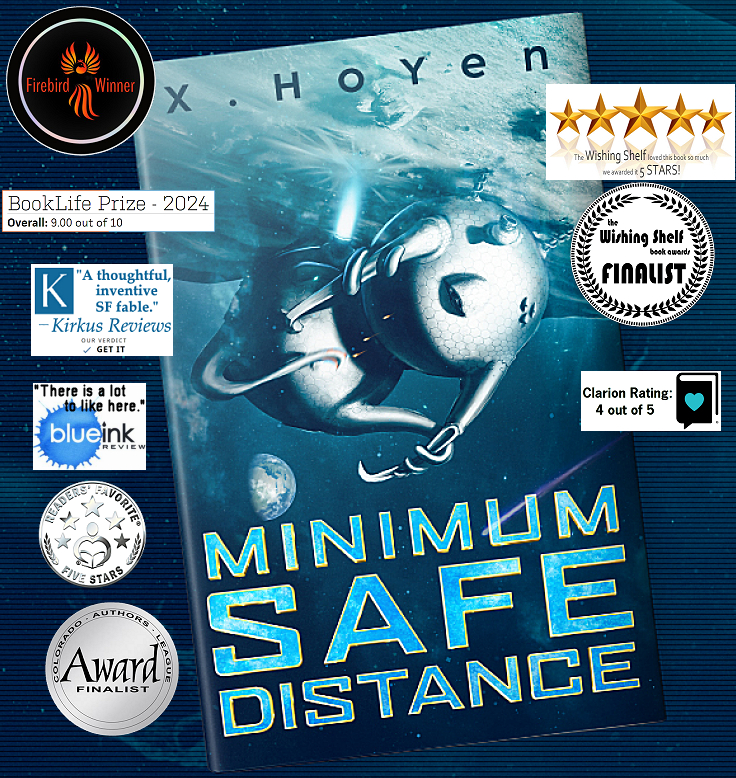

Way back in 2005, right as I was breaking my lifelong Complex PTSD, an idea bubbled up out of my right brain, and my right brain insisted on developing it. I bounced it off a friend, and he said, “Do *not* give up on this idea.” It took me until 2012 to actually start properly writing the manuscript. My friend’s insistence repeatedly got me past self-editing hurdle after self-editing hurdle, confidence hurdle after confidence hurdle. It took another five years to complete the manuscript, and more years to get it read, professionally edited, and polished for release. All those years were also spent learning the craft, of course, especially that last phase working with the professional editor. Interestingly, with a desire to prove that I could write a novel with a completely different flow and tone, my next one took less than half a year to complete. But I can’t help but note that that one is also far fluffier than the first. It’s still literary science fiction, though, not flying rat ray gun material. Both now have legitimate literary awards, the first one in the literary fiction category. My WIP is taking some time, too. I want it to be an improvement, and I won’t rush it.

Hopefully this addresses the question by giving a little insight into my journey, and how I’m not the side-hustle, used car salesman stereotype kind of indie genre writer. And I’m not alone in that. Look at Stephanie A. Gillis’ latest book, “The Humane Society for Creatures and Cryptids”. Or Caitrín Casey’s book “Green Grow the Rushes” (which is becoming a series). Or Kevin Bowersox’s “Tales of the Incorrigible” trilogy. Nobody knows us, but popularity is not a measure of quality.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

This remains on the same topic, because it’s just terribly important. Thanks for the opportunity to frame it this way. Market forces will continue to create a self-fulfilling loop of lowest-common-denominator fiction via the limited categories that vendors want to use (they want a short list), in the same way that Hollywood has done so. It’s self-fulfilling because it continues Hollywood’s trend of training audiences in what to expect and what to want. Remember the “I don’t like science fiction” / “but that’s not science fiction” conundrum. (Movies and tv have the same motivation to keep the categories list brief. I point out that Hollywood utterly failed “Firefly” by playing it out of order and moving it around on the schedule, back before the streaming days. The executives did not know good material any more than Amazon’s advertising algorithm knows good material.)

There’s no fighting that head-on. It’s a force of nature. It’s a given.

So in my view, a society that is concerned about literary quality needs to create active countermeasures to that categorization loop. I applaud curated lists, but those lists have the same problem. At millions of books published every year, more now self-published than trad-published, list curators can’t possibly promote even a tiny fraction of the tiny fraction of that material that’s not merely for escapism even if they wanted to.

What ‘society’ needs are the same kinds of bots and algorithms that Amazon uses, except focused on substance rather than self-fulfilling hits. Vendors just want to light fires. Anything that already has a spark, they’ll promote on the theory that the spark can be blown upon and turned into a fire. Sales, baby! But that algorithm, even though it works for them most of the time, says absolutely nothing about content or quality.

It’s my understanding that external tools are allowed to access the Amazon database. I know there are tools out there for finding categories and aggregating data by sales and category, in service of hustlers who want to write books in niches so they can be big fish in small ponds. (Every new author is bombarded by ads and instructive articles telling them to do just that!)

If so, or in any case *however* it might be achieved, a society interested in creating an active countermeasure (to the self-perpetuating lowest common denominator of sales effect established by internet vendors) should scour book descriptions and posted legitimate lauds, visit author web sites, find other info there, and apply their preferred quality measures, then present entire databases of books organized by entirely different categories, or with different available filters. There are so many ways books can be categorized so as to present more valuable information than the categories used by vendors.

One way to understand what I’m proposing is to look at the question that many authors hate to hear: “What’s your book about?” Very often, the person asking that question really is only interested in the superficial *plot* of the book. Is it about a space hero flying his space opera spaceship in battle against the evil empire? Is it about a “chosen one” who rises from a peasant life to save the realm from the evil wizards? Vendor categories are intended to answer that “what’s it about” plot question, more than anything else. Books don’t have to be categorized by plot topic, and it does the audience a disservice to train them to think they must and to only provide plot topic category filtering options.

Note that this applies to all fiction, not just genre fiction. The vast majority of readers are fine with rapid-output variations on the same stories, maybe with new characters, maybe in a new setting. The big names on grocery store bookshelves have proven this. Patterson and so on. Fine. But even those readers sometimes want something more. How can they find it? With non-plot-centric databases, with databases that allow filtering on information about the author, etc. I see people standing at the bookshelf at the local bookstore, cell phone in hand, doing online searching, maybe for reviews. Reviews are a very skewed way to evaluate a book, entirely dependent on the subjectivity of a few reviewers. (Review systems can be intentionally abused, too.) Rottentomatoes is successful at helping cinema audiences by aggregating reviews, and separating professional reviews from audience reviews. It’s telling how often there is a big disparity between the audience aggregate score and the critics’ aggregate score. I’ve found the rottentomatoes approach extremely reliable in predicting my own enjoyment of a work. The StoryGraph is another such attempt, and I like it. But it just doesn’t have the ad-power that Amazon has pushing Goodreads, and StoryGraph ultimately has the same reliance on few reviewers — statistics of small numbers. A society interested in LCD countermeasures needs to actively cross-promote sites like The StoryGraph. Similarly creative approaches to book categorizations would help readers find what they want, and help good writers find audiences, to the benefit of society as a whole, IMO, and to writers like me! :)

Contact Info:

- Website: https://XHoYenAuthor.com

- Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/@XHoYenAuthor

- Other: https://XHoYenAuthor.substack.com

![]()