We caught up with the brilliant and insightful William Luvaas a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

William, appreciate you joining us today. Can you open up about a risk you’ve taken – what it was like taking that risk, why you took the risk and how it turned out?

For me, as for many novelists, my first big risk was the most significant. Did I dare risk attempting to write a novel? What if I failed? It was like stepping out of a plane hoping your chute opens. I knew I had a good story to tell based on a year I spent living in a crude shelter I built into a giant stump in the Mendocino Coast redwoods, but could I pull it off? Perhaps thirty of us lived on state forest land in teepees, wickiups and tree houses. We saw ourselves not as homeless but as neo-natives: hippies, draft dodgers, nature worshipers, nudists and revolutionaries. It was “Hair” goes “Into The Wild.” Crazy Edward shouted out lines of a play he was writing from his tree house, Red Steve and his stoner crew played bongo drums under the full moon, Jan lived with her kids in a big yellow step van that was a psychedelic dispensary. But our high wasn’t hallucinogens so much as communing with the big trees amidst peace-loving fellow nature lovers. Cin, my future wife (a painter and film maker), moved to the woods with me the very night we met. It was the Sixties, after all, that time of peace, love and revolution. Life was a bit spartan in our tiny shelter, but it was like living in a dream.

In the end, woods dwellers were evicted by lumber company goons. In the novel I began writing some years later, a group of them burned down the sawmill in Fort Bragg in revenge for clear cutting and destroying their paradise.

Writing The Uranian Circus was tough going. There were good days, but at times confidence failed me and I couldn’t write a word. There was so much to learn: how to write compelling characters and dialogue, a gripping narrative, and crisp, evocative imagery so scenes opened up like dioramas on the page. I read Dostoevsky, Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor and James Joyce and tried their techniques. I wrote from multiple points of view, including the POV of an eagle, tried to capture the essence of an LSD trip in a psychedelic word salad, and had swamis emerge from the Pacific ocean on Big River Beach. If you are going to risk failure you might as well go all in. Twelve-hundred manuscript pages in the end.

I sent the finished book to a New York agent. Incredibly, he wanted to represent it. I felt like I was living in a movie titled “I Did It.” Then reality kicked in. The agent liked my book, but said I needed to cut it by two-thirds. I tried, but had no idea how to do that, so my big novel ended up in a cardboard box in the closet.

Was it a risk worth taking since it failed? Definitely. My learner’s novel taught me that I was resolute, ambitious and willing to risk failure. Also, that I needed to learn how to revise.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

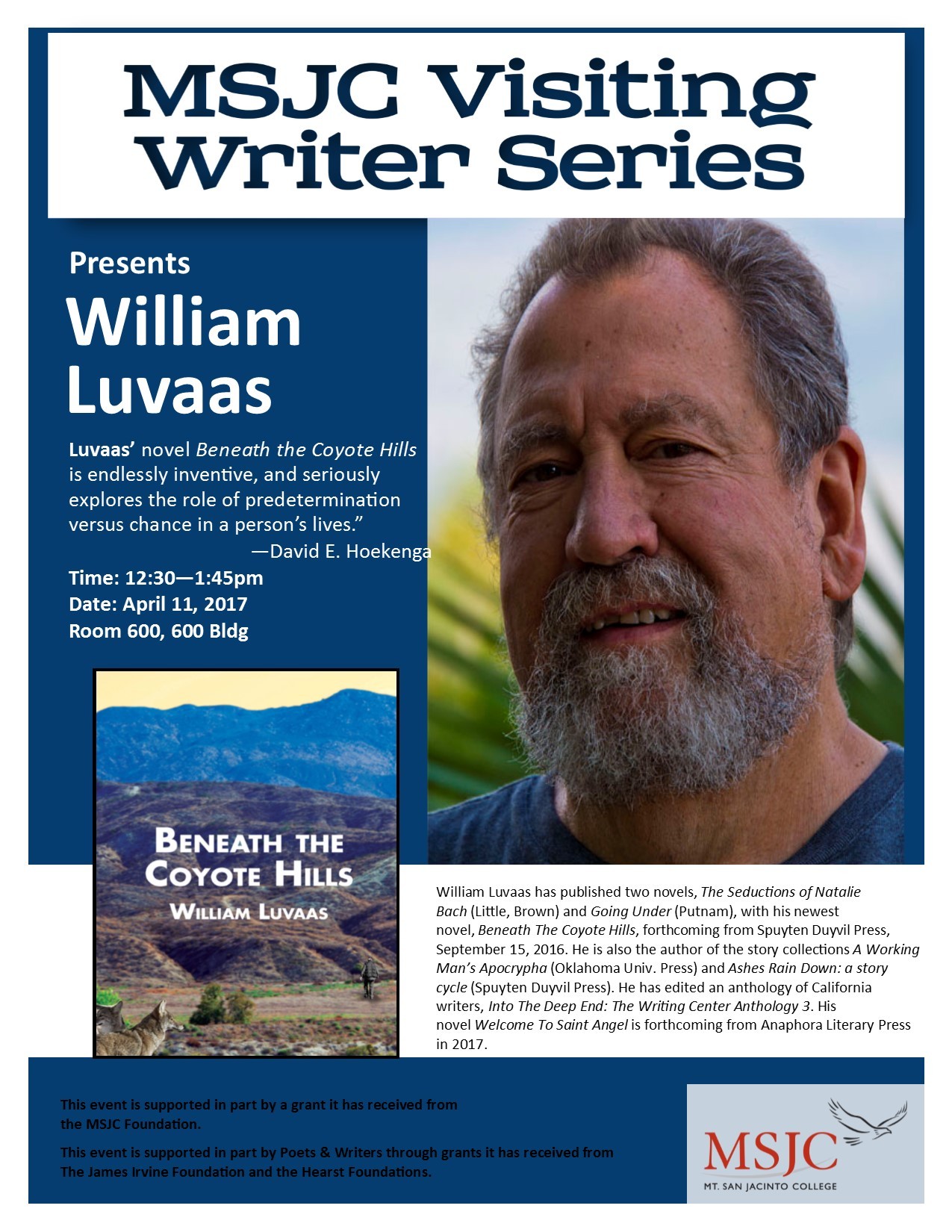

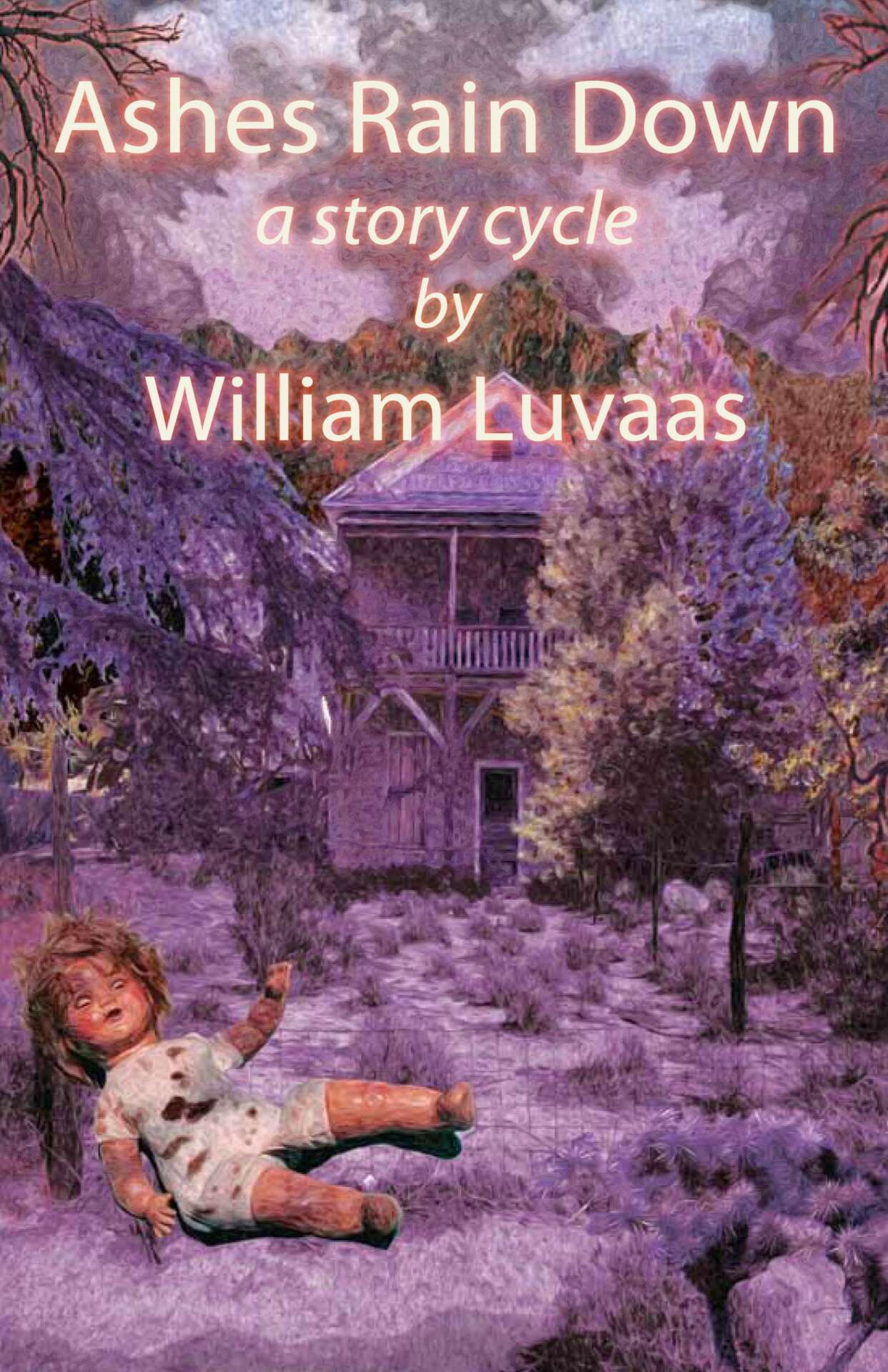

I was attracted to writing fiction because I love storytelling. Moreover, in my writing I can be fully myself, free from the constraints of the world. I have published four novels—The Seductions of Natalie Bach, Going Under, Beneath The Coyote Hills and Welcome To Saint Angel—and two story collections: A Working Man’s Apocrypha and Ashes Rain Down: A Story Cycle (The Huffington Post’s Book of the Year), which is set in a near future when climate change wreaks havoc in people’s lives. A new collection, The Three Devils & Other Stories, is forthcoming from Cornerstone Press. My honors include a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship and first place in Glimmer Train’s Open Fiction Award. My books have been nominated for the National Book Award, The National Book Critics Circle Award and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Over one hundred of my stories and creative nonfiction pieces have appeared in numerous publications

I have taught creative writing at San Diego State University, UCLA’s Writers’ Program and the University of California, Riverside. I’ve also worked as a VISTA Volunteer/community organizer in Alabama, a freelance journalist, and carpenter, and have lived in many places in the U.S. and in England, Spain and Israel. Writers, I believe, need a broad experience of life.

What may most characterize my work is that it’s hard to categorize. It doesn’t fit neatly into any style or genre and contains elements of both literary and commercial fiction. I write about people who face serious challenges and fight to overcome them, refusing to be bullied by fate or see themselves as victims. They are often outsiders living on the fringes of society. My short fiction typically contains elements of magic or grotesque realism: the fabric of reality is frayed at the edges.

I suppose my message to readers is: Don’t be defined by others, define yourself, never lose sight of your goals, never give in to despair, and never ever ever give up.

We’d love to hear a story of resilience from your journey.

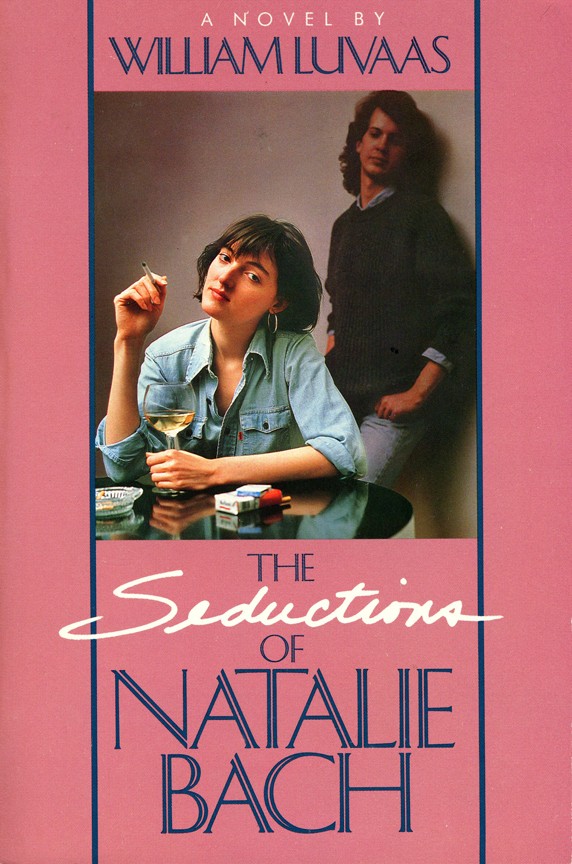

I sent my second novel, The Seductions of Natalie Bach, to dozens of agents, and got nothing but noes. They didn’t think publishers would be interested in the story of a headstrong young woman growing up in New York in the 1960s, trying to find herself in that fraught time when so many young people in America were questioning the status quo. I feared my book was faulted. After all, I’d grown up in Oregon not New York and I wasn’t Jewish. How could I write convincingly from a New York Jewish girl’s point of view? Still, I thought I’d written a good book. I’d done my research; I spent several years living in New York City and my wife was Jewish. After spending four years writing Seductions and two more seeking an agent, I’d be damned if I was going to give up on it. I began submitting my novel to the few major publishing houses that still read unagented manuscripts.

I’d nearly forgotten about my orphaned book when we drove west from our farmhouse in Upstate New York to a family reunion in Washington a few months later. Cin had to drive us home after I twisted my ankle playing volleyball. We arrived, weary and forlorn, to find a mailgram waiting for me:

“Dear Mr. Luvaas: We’ve been seduced by Natalie Bach….Please call me collect.

Congratulations on a fine book.

Sincerely, Mary Tondorf-Dick, Managing Editor, Little Brown and Co.”

After fifty-six rejections, my favorite publisher wanted to publish my novel. It seemed like a miracle. Seductions was one of only three books taken from the slush pile (unagented) by Little Brown in twenty years. Imagine my giddiness after all that rejection to see my book with its flashy pink cover in the windows of New York City bookstores and to sell out the first printing. Heady stuff. Never ever ever give up.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

While it’s gratifying to see your work in print and to get recognition, that’s not what I find most rewarding about a creative life. Acknowledgment is the conclusion of the creative process, closing the door on a work and helping you to feel the process is complete. But it can’t sustain you through the years it may take to complete a work. What’s most gratifying for me is the creative act itself. I can’t imagine building the discipline to be a writer if this weren’t the case. It still amazes me that after a good day at the desk I often feel let down, even vaguely depressed. Why? Is it because I’m spent after being on a roll? I suspect it’s because creativity is a kind of all-consuming conscious dream state, a high of intense concentration when it’s going well. The world around you disappears, supplanted by the world on the page. Few other experiences can equal it.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.williamluvaas.com

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/williamluvaasauthor/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/william-luvaas-3b9b07b7/

Image Credits

Lucinda Luvaas