We were lucky to catch up with William Hartston recently and have shared our conversation below.

William, appreciate you joining us today. Are you happy as a creative professional? Do you sometimes wonder what it would be like to work for someone else?

I’m very happy in a creative role, thank you. My first job after leaving university was for a group of industrial psychologists, using my mathematical insights to interpret and create personality tests. One seminar we ran was going disastrously when some left the course before lunch on the first day. Walking with my colleagues, I said: “This must be terrible for you people who have to earn your living doing this sort of thing.” And that was probably the last time I thought about having a normal, regular job.

I have told both my sons that the secret of life is to do exactly what you want to and hope somebody pays you for it,” and that is basically what I have done ever since.

William, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I think the most important and influential thing determining my career is that I never decided what I wanted to be when I grew up – and I still haven’t. In my school and university days, I played far too much chess at which I twice won the British championship, but I always knew that I would never be good enough to earn my living at it. So I wrote several chess books and appeared in a number of very successful TV chess programmes. When I started work as an industrial psychologist, I had to fill in a personality test and my employers told me that it showed I was very creative. I had never thought of myself in that way, but it meant that they treated my ideas with respect and, to my great surprise, several of them turned out to be very good.

I became chess correspondent of various newspapers including The Independent shortly after it was founded, and it was there that I heard a very bright news editor, when reading a funny piece I had written about the curious players in one tournament saying: “Hey, this man’s wasted on chess”. As a result, I became a sort of unofficial eccentricity correspondent of the paper, and all my writings were tongue-in-cheek and usually humorous.

Several publishers then began to notice me and ask me if I’d be interested in writing something for them, and writing became my vocation.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

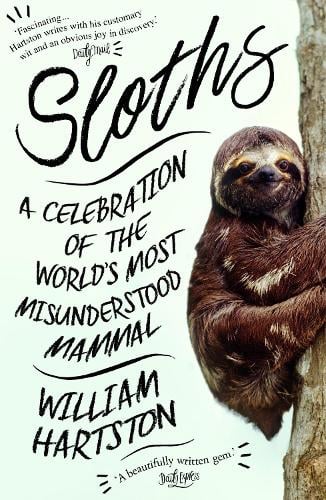

Doing exactly what I want. I have always said that a writer should write books he or she wants to read. My own best example of that occurred when my sons alerted me to internet videos from the Sloth orphanage in Costa Rica. Watching them, I fell in love immediately with baby sloths and wanted to learn more about the animals but as far as I could see there was not a good book about them. So I wrote Sloths, which is by far the most interesting project I have ever taken on.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

Apart from the feelings of independence and control it gives me, I think the best comes when I pursue an idea and it turns out to be even better that I hope. I’ve been writing the Beachcomber column of surreal humour in the Daily Express for 27 years, and sometimes I follow an idea, not knowing how it will turn out until a few lines from the end when I have no idea how to finish it. Then something occurs to me which, when I read it, strikes me as perfect and makes me laugh. When that happens, it is most rewarding.