We recently connected with Warren Feld and have shared our conversation below.

Warren, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you talk to us about how you learned to do what you do?

I had been in health care, high position, very high salary, but hated health care. I reached a point in my late 30’s when money mattered less, and happiness mattered more. I wrote a re-organization plan for my agency and left myself out of the plan.

I decided that selling jewelry would be fun. I began slowly, not sure if this would work, or if I had to return to the dreaded health care industry. Began with flea markets and craft shows. Was doing OK, and felt confident enough to open a small store in an historic district in Nashville. Jewelry was the star seller. It wasn’t long before I tried to make jewelry myself in order to sell it.

I didn’t have a craft or art background. Didn’t exactly know what to do. This was 1989. There was no internet. Just a few message boards. There were no jewelry making or beading magazines. Nashville did not have a jewelry making culture. So everything was trial and error. My sole motivation was to make more money. It didn’t matter at the time whether the money came from making jewelry or selling something else.

In the next few years, everything I made broke. I had strung things on dental floss or leather. Something as simple as learning that the hole size of beads varies was a major epiphany. I’m amazed that I could have ever attached a clasp. Used a lot of hot glue. And that was eye-opening. Hot glue melts at body temperature. Glued-on stones to flat earring posts fell off. Stones glued to pendants rudely found their way to the ground.

I was so determined to get things right. So I began to take in repairs. Very smart move. I saw how other jewelry makers made construction choices and choices about materials. And, with repairs, it becomes obvious what the implications of those choices were. My shop was near the downtown convention center. I got to talk with folks, particularly from California and out west where there was an established jewelry making culture, about a lot of jewelry design things.

I began to formulate my own ideas about construction, design, choosing materials and techniques. And my reputation as a jewelry designer has grown and grown and grown. In fact, my jewelry will be on exhibit at a college art gallery next month.

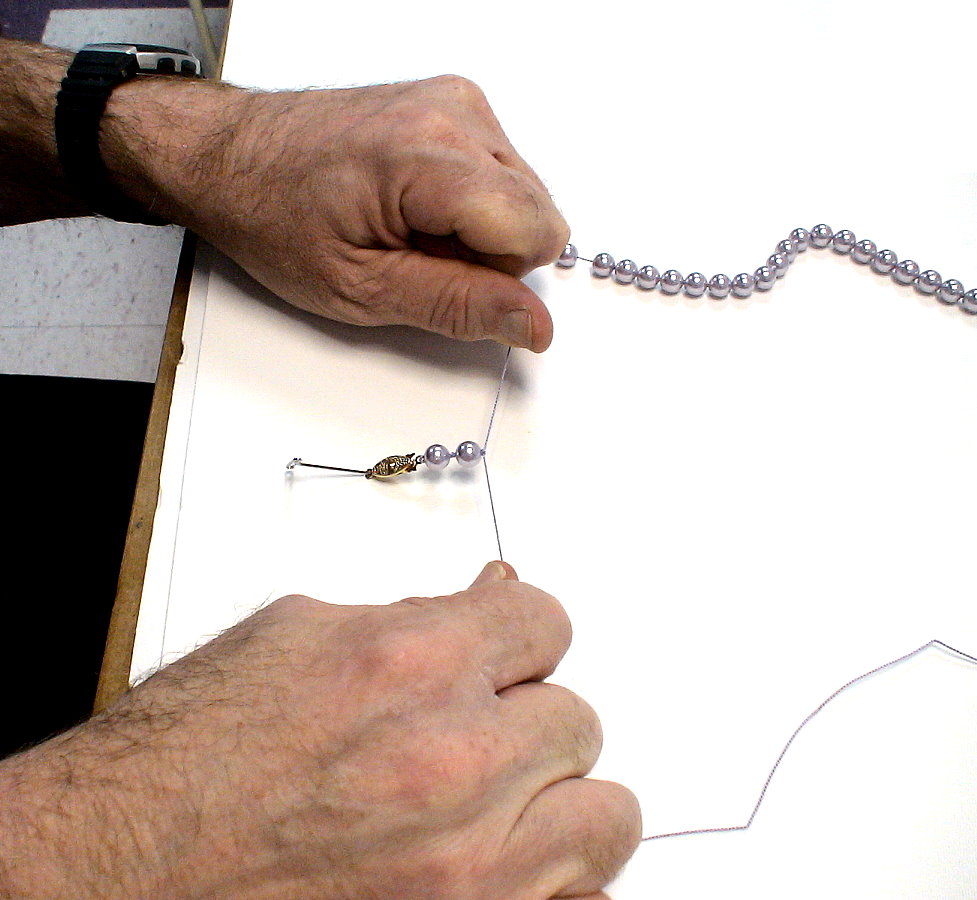

Around the year 2000, I also began to teach. Because I also had this shop where my customers had many varied interests, I taught a wide range of techniques, from silversmithing to wire working to bead stringing, pearl knotting and bead weaving to color and design theory. This turned out also to be crucial to my development as a designer. For one, I got to test out all my jewelry making techniques and design theories and see how many people tried to learn and apply them. For two, this encouraged me to delve more deeply into each technique and design idea than had I only concentrated on learning various sets of jewelry making steps.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

Everything I do begins with the conviction that jewelry can only be considered art as it is worn.

And that creates many challenging dilemmas for a designer like myself. Whether stringing beads, weaving beads, knotting between beads, manipulating wire, fabricating metals, it takes a certain comprehension and fluency in design. With movement, any construction choice takes equal stage with those related to visual appeal. Colors get enhanced, amplified or distorted. Compositions, on the one hand, which if static as in a hung painting, might feel satisfying and complete, on the other hand, when the object is not stationary, the jewelry designer has to resort to new ways of thinking through the arrangements of design elements. My works reflect overcoming these challenges.

I opened a small shop in 1989-90 in Nashville, Tennessee where I sold all kinds of things — jewelry, beads and findings, collectibles, clothing, cards. It quickly became apparent that jewelry and the parts to make jewelry were the star, and the shop gradually evolved in that direction.

At one point, I thought I could make up some jewelry and sell it, thus, make more profit. I made beautiful, sexy, fashionable things — and, for the first 3 years, everything I made broke. This frustrated me. I was determined to figure out why and do better. Towards this end, I started taking in repairs. This gave me insight into the variety of design choices to be made, and the implications of those choices, especially since there had to be a reason why a piece of jewelry broke. This also gave me a chance to talk with the customer and get some idea of the history of the piece, and the situation in which it broke.

In 1999, I organized a group of jewelry makers and instructors to create an education plan for a jewelry design school. The task was to see if we could come up with any kind of standard education, a pathway through classes, and something relevant to all types of jewelry makers from bead stringers to metal workers. The group interviewed instructors and craft organizations all over the world. They came up with a model that grouped skills into sets, where they would be taught as a set so that the students can see the interactions among them. Lots of key stuff here, but to highlight, every technique has as part of its procedures some steps which are there to maintain shape, and other steps which are there to assist in movement, drape and flow. People don’t learn steps that way. They learn to follow a set of steps, 1, 2, 3… etc without learning the design implications for each step. That was our concern and focus.

For example, you see a lot of women wearing necklaces which have turned around on their necks. This is not natural to jewelry. This is a design problem. It shows that the choices made to create and attach the clasp were insufficient to the task. And it’s very easily solved, usually by adding a couple more jump rings on either side of the clasp. No matter if the woman is sitting or doing jumping jacks, the necklace will never turn around the neck if designed properly. Easy to demonstrate and very easy to teach.

We wanted to train design professionals, not crafters. Implementation was a little rough an awkward at first. Most students wanted to take a class, make something, and wear it. They didn’t necessarily want to learn both theory and application, nor have to take 2 classes in order to make a piece. Teachers didn’t want to do the work we required of them — written instructions, sequencing of 4 classes, physical samples. Teachers could earn the same money working at other shops and organizations without have to do any of these things. But as our reputation for insight and excellence grew, the students came and I was able to find teachers who bought into our program.

Over time, I developed a lot of theories about design. The educational program I created gave me multiple chances to test the ideas out, come up with new ideas, modify ideas, tweak things. I wrote 5 books summarizing my ideas. I’m very proud of these.

As part of our educational program, I created 3 international contests. These contests were set up to be design competitions, not beauty pageants. The biggest one, which we ran 10 times over 15 years, was The International Ugly Necklace Contest. It turns out, because we are prewired with a fear and anxiety response, that we’re pre-biased towards making beautiful things, and it becomes very difficult to fight our inclinations in order to make something ugly. The better designer can get there. Related themes were the focus on our other two contests where the better designer had more control over managing the structure of a piece and its visual appeal — typically requiring tradeoffs in design choices. These contests were: All Dolled Up: Beaded Art Dolls, and The Illustrative Beader: Beaded Tapestry Competition.

My pieces have appeared in books. One piece — Canyon Sunrise — was a finalist in a Swarovski competition and resides in their museum in Innsbuck, Austria. This coming September through October, the Pryor Gallery at Columbia State will hold an exhibit of my jewelry.

Do you think there is something that non-creatives might struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can shed some light?

Non-creatives don’t realize the amount of effort and knowledge that it takes to create a piece. There’s an assumption that anyone can do it. Related to this is that the world is not sure whether jewelry should be considered an art form or merely a craft. Many art galleries will not carry jewelry because they see it as a craft.

So I spend a lot of time educating people. I don’t get snotty or snooty about what I say. I try to tap into their sense of empathy and lead them through the design process as if they were making the choices themselves. I get a lot of wide eye openings and ah-ha moments.

This isn’t that difficult. For example, I can point out places in the jewelry where my choices were targeted at maintaining the shape, and other places where my choices were targeted at making the piece more comfortable to wear as the person moves. Or with pearl knotted piece, I can easily show how the way I string pearls and makes knots enhances the piece architecturally and reduces the chances the string will break. Or to prevent necklaces from turning around on the neck, it takes about 3 minutes to fix and show them what I did.

Is there mission driving your creative journey?

I am mission-driven. My mission is to bring a professional model of study and implementation to jewelry design.

The step-by-step craft model is insufficient. In fact, for a lot of what a crafter would do, a computer and machine can do the same things faster and better, and sometimes with more creativity.

The visual appeal goal of the art model is insufficient. Jewelry is something much more than an object to be solely judged based on beauty and laying in a stationary position on an easel.

The world needs a more professional design model to underly how jewelry making is taught and how jewelry making is implemented in the real world. Jewelry is not a painting hanging on a wall or a sculpture fixed on a pedestal. It moves. It instigates conversations. It represents or signals something personal about the wearer. It has to function as the person moves through different light and shadow, different contexts, interacting with different people. Jewelry is more an intent than an object. It conveys meaning in context, and which can change as the context changes. Designers need to anticipate all this and more, and then incorporate these understandings when making choices about materials, techniques, compositions, constructions and manipulations.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.warrenfeldjewelry.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/warrenfeld/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/warren.feld

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/warren-feld-jewelrydesigner/

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@oddsshop

- Other: Medium https://medium.com/@warren-29626

Patreon https://www.patreon.com/warrenfeldjewelry

Blog blog.landofodds.com

Image Credits

all images taken by myself Warren Feld