We were lucky to catch up with Tony Brinkley recently and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Tony thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. How did you learn to do what you do? Knowing what you know now, what could you have done to speed up your learning process? What skills do you think were most essential? What obstacles stood in the way of learning more?

I learned (am still learning) to do by doing. When I was a teacher, I said to classes: 1.) Don’t worry about what I want. 2.) Discover what you want. 3.) Now don’t worry about what you want. Discover what the work wants. Your work will teach you how to do it. Your work is your best teacher.

I try to practice that myself. Goddard said of cinema: what you don’t see is incredible. The craft teaches you to see what you don’t see.

In Shakespeare you will notice that the deepest insights about human nature come from the craft of acting.

Tony, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I lie the experience of changing my mind, the experience of change in thoughts of things and things of thoughts. John Cage said that he was less interested in self-express than in self-alteration. I also have that interest.

When I used to teach literature (Romantic Studies, Holocaust Studies, Soviet Studies, all kinds of studies), I did best when I discovered what I was teaching while I was teaching it. I liked improvisation – never quite knowing what would happen next – like experimental jazz.

While teaching at the University of Maine, I also was an active player in Maine politics. At the University, I coordinated the creation of the Wabanaki Center and academic program. I did what was necessary to prevent the University from eliminating programs for Maine’s Franco-American communities (Franco–Americans are the largest demographic group in Maine). I initiated a program that made technical education an aspect of the liberal arts. In areas of concern and through political alliances, I could sometimes dictate policies for the University – one of the reasons I was retired. I successfully worked through arbitration with the University and as a result have had a prosperous retirement. I tried not to underestimate the systemic mendacity, arrogance, and stupidity that characterizes university life and was able to win when I needed to. In my last years as a college professor, while I was volunteering in the Maine State Prison, I was surprised to find a spiritual environment far more powerful than anything I found at the University of Maine. In many ways I have been blessed.

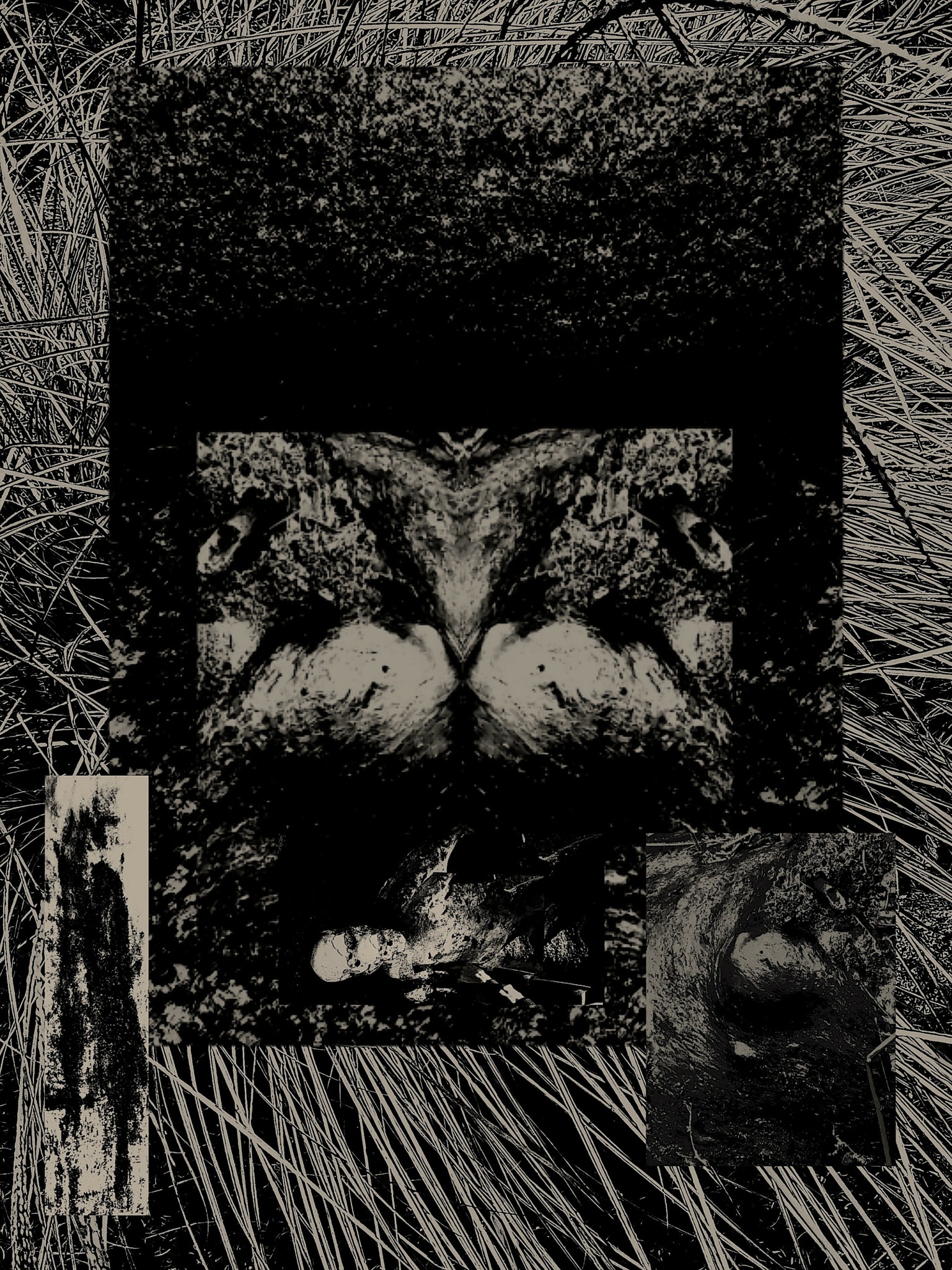

I write poems and make icons which I think of a poems without words. Here is an introduction I’ve written for one project: ICONS OF WAR (perhaps this is the best way I can tell you about my work);

So I am still and I am silent, because if I

open my mouth, I may never stop screaming.

— Franz Kafka

When bewildered Russian soldiers invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the appearances of things and of the life in things changed. News from a distant war infected the everyday, and we could see what we hadn’t seen before. Of course, this could have happened earlier – there was never any shortage of catalytic atrocities (they were – they are – everywhere to name) – but we had had the vigilance to screen them out (however acknowledged) at the borders of vision in order to maintain – more or less – an emotional oblivion. And then the war came. And the look of things altered if we looked into their life. For the most part there was nothing you could say, but the change could be everywhere to see.

I was already aware of this phenomenon from Wordsworthian poetry where memories from childhood become icons of imagination and intimations of mortality and immortality. A similar phenomenon occurs in Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah where voices of memories turn the landscapes Lanzmann films into icons of the Holocaust. When you hear rifle fire while walking in the woods, it can become an icon of war and its recurring traumas. The head of a burned match turns into a human face, a pile of burned matches into an image of desolation. Landscapes become battlefields. Souls appear in photographs of ashes. Things turn into imprisoned souls.

In 1940 Walter Benjamin wrote that “the tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of emergency’ in which we are living is not the exception but the rule. . . The current amazement that the things we are experiencing are ‘still’ possible in the twentieth century is not philosophical. The amazement is not the beginning of knowledge – unless it is the knowledge that the view of history which gives rise to it is untenable.” Still in the winter of 2022 the shock was (and the shock continues to be) palpable.

Confronted by European fascism and writing about The Iliad, Simone Weil thought that a product of war’s violence was reified life as an artifact of force:

To define force — it is that x that turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing. Exercised to the limit, it turns man into a thing in the most literal sense: it makes a corpse out of him. Somebody was here, and the next minute there is nobody here at all.

This spectacle for the living undead induces terror, “the force that does not kill, i.e., that does not kill just yet”:

From its first property (the ability to turn a human being into a thing by the simple method of killing him) flows another [force], quite prodigious too in its own way, the ability to turn a human being into a thing while he is still alive. He is alive; he has a soul; and yet — he is a thing. An extraordinary entity this — a thing that has a soul. And as for the soul, what an extra-ordinary house it finds itself in! Who can say what it costs it, moment by moment, to accommodate itself to this residence, how much writhing and bending, folding and pleating are required of it? It was not made to live inside a thing; if it does so, under pressure of necessity, there is not a single element of its nature to which violence is not done.

And Putin’s War: it is only one of many catastrophes, many unnoticed – and then you notice. The desolations of Sudan, Gaza and October 7 devastate the commonplace. This world is not this world. As Aleksei Navalny said not long before his murder: “You start to realize the degree of horror.”

And icons: Just as any object can embody the Buddha and center a space if regarded as such, just as every thought can become a koan if received as a koan, images become icons if they face you as icons. Pavel Florensky writes that an icon is an appearance of the energy for which it is the leading wave. As the wave floods in the mind, the appearance dissolves but its spirit becomes palpable. Of Pushkin’s poetry, Boris Pasternak writes that “light and air, the noise of life, things, essences burst from outside into the poem as into a room through an open window.” This is also the aesthetic of icons. Life enters the poem the way the icon visits the soul, and if this is true for the noise and life of things, it is also true for their desolations, ruins and devastations. In my eyes the poems without words that I could find in photographs of things became icons for terror and love that coexisted as incommensurates in my mind. Inevitably this coexistence for me and for everyone pre-existed 2022, but for some of us Putin’s War made it visible again and as if for the first time. Outcries became visible if not audible, silenced by acoustic shadows. Our shock testified against us.

When icons become poems without words, gazing complements reading. These icons began with moments of pareidolia, of seeing imaginary things that I could find in the photographs I was obsessively taking at the time. From this beginning other icons emerged (without knowing it, I was adopting an approach that Leonardo da Vinci recommends for painters: “Look attentively at old and smeared walls, or stones and veined marble of various colours; you may fancy that you see . . . heads of men, various animals, battles, rocky scenes, seas, clouds, woods . . . It is like listening to the sound of bells, in whose peeling you can find every name and word that you can imagine”). Starting with photographs of the things around me – in the house, in the yard, on the street, in the garden. I began to see what my phone could picture; as I looked at the phone’s tiny screen, as I edited the photography with the limited editing, rearrangements and montage for which the phone allowed, I found images I hadn’t seen before but (like the animals that surface from the face of clouds or the rock walls in paleolithic caves) were beginning to come to life. I began to see what my mind was ready (but unprepared) to witness: poems without words, icons that faced me. When I listened, their voices were shadows (sometimes like hungry ghosts or good dybbuks) that I could almost overhear.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

What is TELOS or final cause that shapes a creative journey? Since the journey is endless, the final cause is necessarily tentative, changing, metamorphic? About to be?

As an imperative, I think of a saying that may be Jewish: “a just person lives in a universe were justice exists.” Any triumph for justice may be a forlorn hope, but you can always assure that justice exists. All that is required is that your actions be just. The same might be said of goodness or love, generosity or kindness.

Osip Mandelshtam said that you write poems for a future, unknown reader who listens with the intensities of a lover to your love, terrors, fears. It’s final cause is this listening. It is important that the reader be unknown and in the future because then what they hear will surprise you – it is a way of surprising yourself.

The subject of the poetry I write and the icons I discover is almost always love and terror. They co-exist. Each have lives of their own.

Since I am 77, I suspect that what is driving me now is a gradual sense of dying (or what the BHAGAVAD GITA – at least in translation – calls “disembodiment.”). I have a sequence of poems that I am working on which is tentatively titles DEATH SENTENCES. An author’s note:

When you get older – as I have (77 years) – you find yourself (more or less gradually) becoming disembodied (physically and also mentally). The experience can feel addictive as realities become palpably more intensive and less extensive whether as an inner space that you contain or inside the outside in which you are only a very small part.

DEATH SENTENCES attempts to engage this experience (often celebrate it) in words but also without words – in icons (or poems without words). The icons are not illustrations. Perhaps they bring reading to a momentary standstill. I hope they can turn reading into gazing and gazing into another way of reading words and phrases.

Of Pushkin’s poetry, Boris Pasternak writes that “light and air, the noise of life, things, essences burst from outside into the poem as into a room through an open window.” This is also the aesthetic for icons. Life enters the poem the way the icon visits the mind. Pavel Florensky (a Russian priest murdered in the Gulag) said that an icon offers an appearance for energy (impulse, spirit) for which it is the leading wave. As the icon addresses us and as we receive its images, its appearance disappears but its energy remains palpable in the intensities we experience as inner life. The icon becomes the material cause for a changing mind. I hope that the words and icons in DEATH SENTENCES offer change in this way.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

I have had to learn that it is not helpful to think of myself as a teacher, scholar, politician, poet or artist. That’s what would make the work about me. That has always been a wall I could run up against. Teacher, scholar, politicians are roles I learned how to play – performances (at the most fundamental level – consciously or unconsciously – Shakespeare thought we were all of us actors). I like to think I write poetry and make art without being a poet or an artist.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://umaine.academia.edu/TonyBrinkley

- Other: [email protected]

Image Credits

All my own.