We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Tim Weed. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Tim below.

Hi Tim, thanks for joining us today. Let’s jump right into how you came up with the idea?

I was working as a traveling lecturer for National Geographic Expeditions on small-ship cruise through Tierra del Fuego: Ushuaia, Argentina, to Puntarenas, Chile, via Cape Horn, the Beagle Channel, and the Straits of Magellan. There were some interesting fellow-passengers aboard: in particular an astrophysicist who was the director of Hawaii’s Mauna Loa observatory and a young paleo-climatologist from Princeton. Needless to say, we had some fun conversations in the ship’s panoramic dining cabin!

At the time, I was casting around for a new fiction project. I’d published a novel and a collection of short stories. I wanted to write another novel, and I was looking for subject matter that was bigger: topics like geological time, the climate crisis, the biodiversity crisis, and the potentially clouded future of the human species itself. My interest was partly aesthetic—I thought it would be an interesting challenge to take on these big questions in the context of a novel—and partly for the sake of my own sanity. As I’m sure is the case for many of us these days, I’d been brooding and worrying about the future.

So I knew more or less what I wanted the novel to be about, but I hadn’t really figured out how to write it. Then suddenly, in the middle of a casual dinner-table conversation—with the vast unpopulated wilderness landscape of Tierra del Fuego to sliding by outside the ship’s picture windows—an idea came to me, and I asked the astrophysicist about the plausibility of one-way time travel into the deep future. He took on the thought exercise with gusto, and in a series of complex equations involving general relativity and quantum physics scribbled on napkins, was able to demonstrate (to his satisfaction at least) a mechanism for one-way time-travel 10,000 years into the future that was theoretically possible using technology easily imaginable or currently in development for interstellar travel.

I had permission to run. It would take a lot of research, a lot of imaginative work, numerous full drafts, but the novel that would eventually become THE AFTERLIFE PROJECT was on its way.

Tim, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I’ve been seriously studying and writing fiction for nearly 30 years. After about a decade of writing and trying, I finished a story collection and got an agent for it. That agent was unable to sell it, and eventually we parted ways. I wrote a lot of stories, and several multiple-draft novels that ultimately failed. After almost giving up I finally sold my first novel unagented, to a wonderful small publisher. I was very happy with that novel, WILL POOLE’S ISLAND, and the way it was published and the reception it got, but it didn’t sell more than a couple of thousand copies. Not enough to make a living on, certainly—far from it. But it helped me to establish the beginnings of a small readership.

After that I managed to sell that original story collection, A FIELD GUIDE TO MURDER & FLY FISHING, to a different small press. Again I was happy with the way it came out into the world, and this one did slightly better than the first novel did, thanks to some lucky breaks and the hard work of my publisher and myself. Both the novel and the collection continue to sell in dribs and drabs, but with a small press there are built-in limits. You can get it into a few bookstores, and reach many readers online, but with a small press it’s never going to be in airports. Still, I was happy with both the first novel and the story collection and still am. And I think that’s really important. You want to be proud of what you’re putting out there, which is why you really don’t want to send a book out until you’ve taken it as far as you can. And then if you’re lucky, you get connected with a good editor who sees what you’re trying to do and can help you make it even better. Because once you publish a book, it’s out in the world forever.

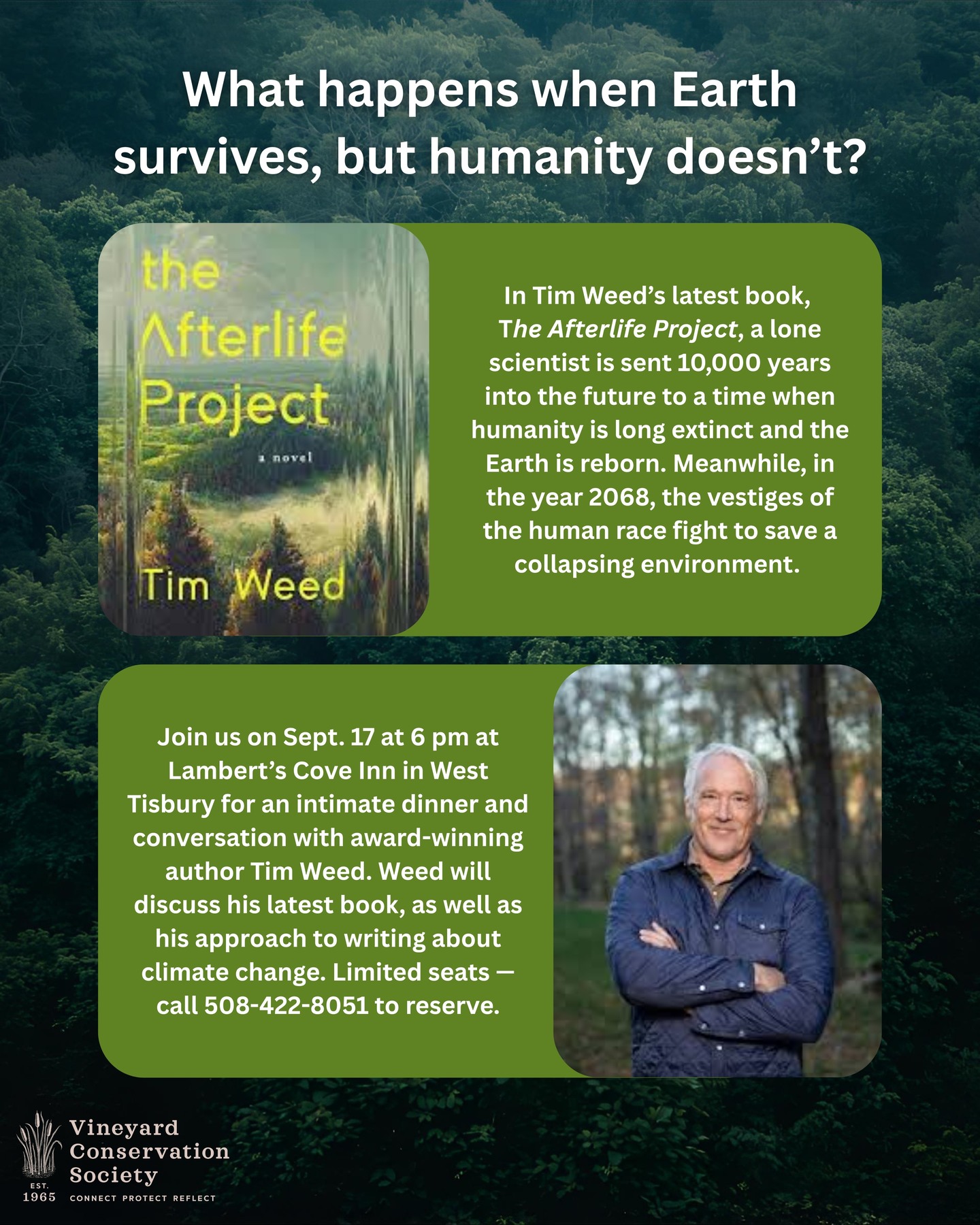

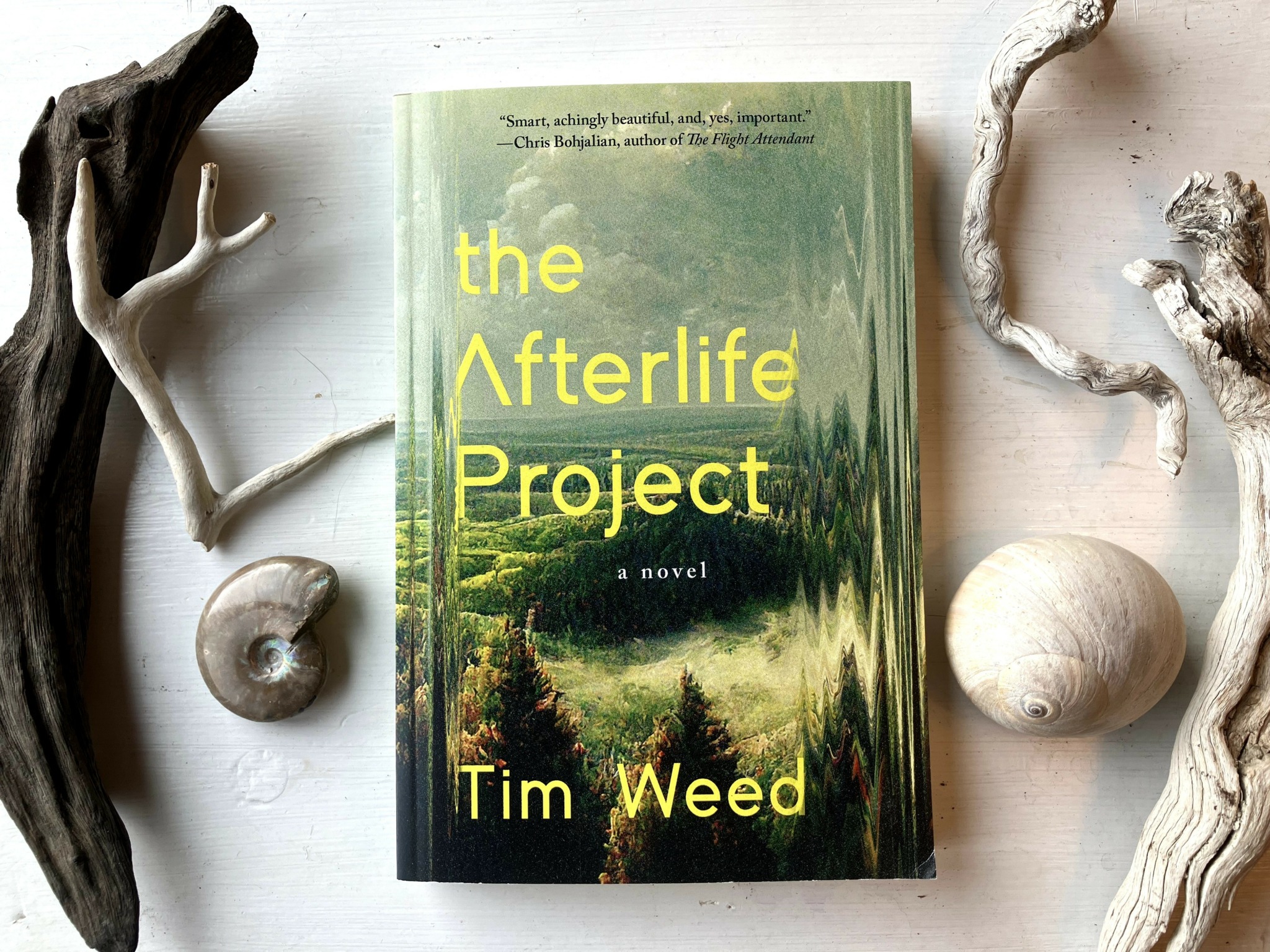

I’ve always enjoyed the process of writing fiction. It’s a challenge that I love to embrace—to create a story that comes alive on the page, that is entertaining and immersive, and that gets at some kind of deeper truth. In terms of the subjects of my fiction, in one sense I spent my early career looking backward. I went from autobiographical stories to historical novels; more recently I’ve started looking to the near and distant future. THE AFTERLIFE PROJECT, which came out in June ’25. is a work of speculative fiction that will appeal to readers of Emily St John Mandel, David Mitchell, Cormac McCarthy, and Richard Powers. Featuring a post-apocalyptic sea voyage on a vintage sailing yacht, lovers separated by 10,000 years of time, and pervasive dangers both physical and psychological, and a future that is by turns terrifying and hopeful. It was a finalist for the Prism Prize for Climate Literature, a New Scientist Best New Science Fiction Book of the Month, and a Middlebury Magazine Editors’ Pick.

The publisher, Podium Entertainment, which has been absolutely great to work with. The book has seen quite a lot of success out in the world, and I’m very happy to be in this position after many years of struggle. My next novel, THE GATEPOST, comes out in May ’26.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

My goal is to write fiction that is exciting and immersive for readers, while at the same time taking them on a deeply felt emotional journey. Fiction, more than any other art form, enables a reader to experience the world from within a consciousness that’s not their own, imagining alternative lives and alternative futures—sometimes very dark ones—from the relative safety and comfort of one’s favorite reading chair. Putting oneself in the position of fictional characters as they confront tense and difficult challenges; and then processing those experiences and the emotions they evoke into wisdom or at least working theories about life, is a cathartic, healthy, and uniquely human practice.

In terms of THE AFTERLIFE PROJECT specifically, my hope is that it offers both a reminder that humanity needs to take action now in order to avoid the worst outcomes, and a kind of optimistic prediction about nature’s capacity for healing, at least in a deep future time-frame. If there’s one piece of wisdom I would like readers to take away from reading the novel, it’s that we’re not facing the end of the amazing, ever-evolving story of life on Earth. Far from it. Rather, we are—or should be—facing the end of the illusion that humans are not part of nature; that we haven’t from our very emergence as a species been embedded in the ebb and flow of this complex and beautiful 4.5 billion year-old planet.

This would be a timely and necessary paradigm shift. Because it’s still not too late to save ourselves.

Have you ever had to pivot?

[This story is taken from my essay, “Turning Out the Lights,” originally published in CRAFT magazine]

The blackout was a revelation. It happened at around eight PM, in Trinidad, Cuba, on one of those moonless tropical nights that fall so suddenly you barely notice the dusk. This was several years ago—before the loosening of travel regulations that occurred under President Obama—and the number of American tourists remained small. In common with many others who’ve dedicated their lives to the dream of producing enduring literature, I’ve had to make my living by other means. I was a Spanish major in college, and through a series of happy accidents I ended up developing a parallel career as an educational travel guide with specific expertise in Cuba. Before the resumption of diplomatic relations, organized cultural travel programs provided a highly sought after legal method for Americans to travel to the country, and my knowledge base was much in demand. At the time of the occurrence described in this essay, I was traveling to the country with cultural tourism groups at least half a dozen times a year.

Trinidad is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a remote city nestled into the base of the Sierra de Escambray mountain range, overlooking a notably depopulated part of the Caribbean. For much of the Spanish colonial period it was a wealthy sugar capital, but in the second half of the nineteenth century—with the end of slavery and the economic devastation that came with the wars for Cuban independence—the city entered a long period of desperate poverty and near-total isolation. This period only ended with the construction of the first highway linking it to Havana in the 1950s, and the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 ensured that Trinidad, along with the rest of the island, would remain closed off from the main currents of the late twentieth century world economy. As a result of all this, the city is a living time capsule. Horses clop along the cobbled pedestrian-only streets in the hilly upper reaches of town. Through the wood-grated windows of the high-ceilinged colonial houses one can still see the original nineteenth-century furniture. In a few of the interior courtyards horse-drawn buggies remain parked, as if waiting for their owners to come back and rig them up.

Cuba is not a brightly lit country to begin with. The electrical system is antiquated, and although blackouts are less common now than they were during the deep economic depression that followed the collapse of the Soviet Bloc in the 1990s, they do still occur. Trinidad is far removed from any other source of ambient light, so even without a blackout, on a moonless night, the stars emerge in a brilliant textural canopy.

When the electricity cut out I was “off the clock,” eating dinner on my own in one of the dozen small restaurants near the Plaza Mayor. There was a moment of cave-like blackness accompanied by silence. Then the quiet conversations around me resumed, and a few candles flickered to life in the surrounding establishments. Before long the center of town was dotted with spheres of trembling amber light. A horseman trotted by, the iron-shod hoof-beats ringing clearly across the square as if to complete the illusion of having traveled backwards in time.

Finishing dinner, I wandered out to sit on the coral-stone steps of the cathedral. A pleasant breeze blew up from the sea. The steps still radiated the warmth of the tropical sun.

And the revelation?

Well, before I can describe it, I have to explain something about my state of mind. Making a living as an international travel guide may sound like a sweet gig, but like any other repetitive job, it can get old. You’re always “on,” for one thing, which is a daunting prospect for an introverted writer: Imagine hosting a nine-day cocktail party. Then there’s the boredom of following the same crowded itineraries, meeting with the same interesting locals, and participating in the same festive activities year in and year out. In my personal life I treasure the opportunity to be active, but most high-end cultural programs are surprisingly sedentary, featuring long air-conditioned bus rides, a great deal of passive spectating, and twice daily, multi-course group meals in five-star restaurants. So even though my “day job” was bringing me to some of the most interesting and picturesque places in the world, I was only half-experiencing them. I was preoccupied with logistics, small talk, and the draining, insincere gregariousness the host role demands. My off hours were spent walking in numb distraction, dining alone at a familiar bar, or hiding behind potted plants in a hotel lobby checking my email. I’d become jaded.

This gets us back to the blackout—and the revelation I had while sitting on the steps of the cathedral in Trinidad. After my eyes had adjusted to the darkness, I was suddenly overcome by a sharp awareness of my relationship to the physical landscape. Not just the abstract knowledge of where I was geographically. Not the conjured image of a point on a map, nor even a self-conscious awareness that I was sitting in a socio-politically unusual location: a remote, historic World Heritage Site in a poor region on the south-central coast of the western hemisphere’s only communist country. This was different. Suddenly, I had a visceral sense of my exact location in the three-dimensional topography: sitting at the head of the cobbled plaza at the center of a centuries-old town, at the base of the towering karst mountain range that formed a jagged ink-black wall in the night sky at my back, on a sort of elevated shelf overlooking a tropical sea that glittered faintly in the distance beneath the overspreading stars.

The intensity of this shift in perspective took me by surprise. All at once I’d recovered a sense of connection that I hadn’t even realized was missing. It was a big, reassuring, exhilaratingly physical feeling of communion with the land and the sea and the universe of stars.

When the electricity came back on, the three-dimensional majesty of the nighttime topography evaporated, leaving me with a sense of emptiness and loss. We’re used to blaming our technological gadgetry for keeping us at arm’s length from what we call “real life,” but for me, the blackout was a reminder that the problem goes deeper than the latest generation of smartphones. Electricity itself—that clever sine qua non of advanced industrialized society—is a force that imprisons us, because it prevents us from seeing out into the darkness. The live current we’ve tamed and channeled may provide a reassuring background buzz, but it keeps us from experiencing the sublime truth of the material universe and our precise location within it.

#

Absent fortuitous blackouts, depending on the kind of person you are, receiving this kind of visceral reminder of the true nature of existence may require either drugs or a deep-seated commitment to silent meditation. Wilderness camping might do it for you, as it often has for me, especially for multiple nights in a row. Even for a brief time, immersing yourself in one of out planet’s sublime landscapes is also a good bet. I’ve had moments of heightened awareness blossom back into my consciousness on hikes in the red rock deserts of the American southwest, on skis in snow-blanketed Rocky Mountain conifer meadows, and sitting at the rail of a small ship cruising through the Beagle Channel as the jaw-dropping peaks and hanging glaciers paraded magisterially by. If you haven’t been fortunate enough to experience one of these jolts recently, it’s possible that you may have become jaded. As with any rigorous pursuit, unused muscles can atrophy. Sometimes you have to exert your willpower to rekindle the connection.

And this is where writing comes in. I once heard the poet David Baker say that literature can be divided into two categories: the ironic and the ecstatic. Ecstasy is transcendent, mystical, implying a state of trance, vision, or dream. Irony, on the other end of the continuum, is social, worldly, rooted in the intellect. In blackout terms, irony is electricity, and ecstasy the unmediated tropical night.

Irony is essential in literature as an antidote to sentimentality, but in my view the most immersive writing is to be found on the ecstatic end of the continuum. When we write, we want the reader to forget all about those black marks on the page and tumble headlong into the narrative as one would fall into a trance. Good descriptive writing is what triggers this loss of conscious control, this benign fugue state; it’s what puts the vivid in John Gardner’s “vivid, continuous dream,” and it’s my belief that in order to produce good descriptive writing a writer must, at least intermittently, have access to something analogous to my blackout revelation. She must be able to turn off the electrical currents of irony and intellect and connect to the surrounding world in a way that is intuitive, instinctive, and ecstatic.

#

These days, if I happen to be talking to a group of aspiring writers, I may be tempted to give them some version of the following advice. Close your laptop. Turn off your smartphone. If you’re lucky enough to find yourself in a blackout, don’t forget to look up and notice your surroundings. And if there’s no blackout, just turn out the lights.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://timweed.net/welcome/the-afterlife-project-a-novel/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/timweedwriter/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/timweedauthor/

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCRgNB3oqNVaKCxI9HB4ugbw

Image Credits

the headshot is from The Brattleboro Reformer