We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Tenola Plaxico a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Tenola , thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Have you been able to earn a full-time living from your creative work? If so, can you walk us through your journey and how you made it happen? Was it like that from day one? If not, what were some of the major steps and milestones and do you think you could have sped up the process somehow knowing what you know now?

I believe that many artists pathway to being a full-time creative is marked by the same sort of circuitous journey. After getting a degree in literature, and working in at at least five or six different industries, I returned to photography -a hobby I developed while in college- and latched onto it in hopes of making it a sustainable form of income. It was never my “invention” to be a professional photographer. That wasn’t even something I could conceptualize when I was imagining/designing the framework of what I would do long-term. But, working in a job that you despise is the greatest catalyst for moving you forward towards your passion. I’ve worked in sales. Law enforcement. Publication. Education. Non-profits. Each of these jobs invariably contributed to the vast and intricate tapestry of my journey. They taught me the things that I would not tolerate. They taught me the things that I should look for in viable and valuable business relationships. They taught me how to establish the parameters of healthy boundaries. They taught me how to assess my own value.

So, even though I resented a lot of those jobs, they still prepared me for the swirling array of challenges, hurdles, and wonders that are entrepreneurship. As much as I would love to say that having the support of my parents, and a studio, and better equipment, and an extensive arsenal of different tools could’ve catapulted my career into the stratosphere a lot sooner, I also think they would’ve hindered me. Starting off in photography knowing that the only way I could make this work was by being absolutely excellent was the impetus to do truly peerless portraiture. There was no backup plan, necessarily. And, my first camera was really more of an amateurs trifle than a proper professional tool. But, that camera got me commercial jobs all over the world. Learning how to use the bare minimum to get exceptional photos turned out to be a blessing in disguise.

Tenola , before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

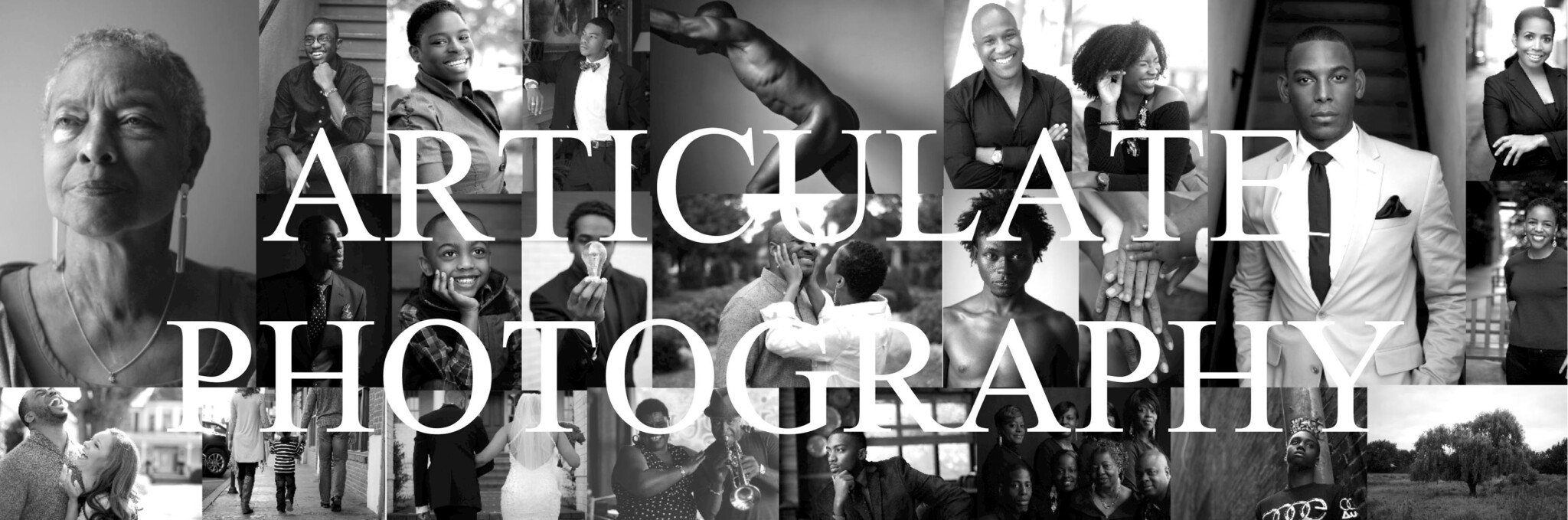

I am a lifestyle photographer based in the Greater Memphis area, specializing in a professional headshots, weddings, branding, and marketing, food, cars, children, events, real estate, abstract, etc.

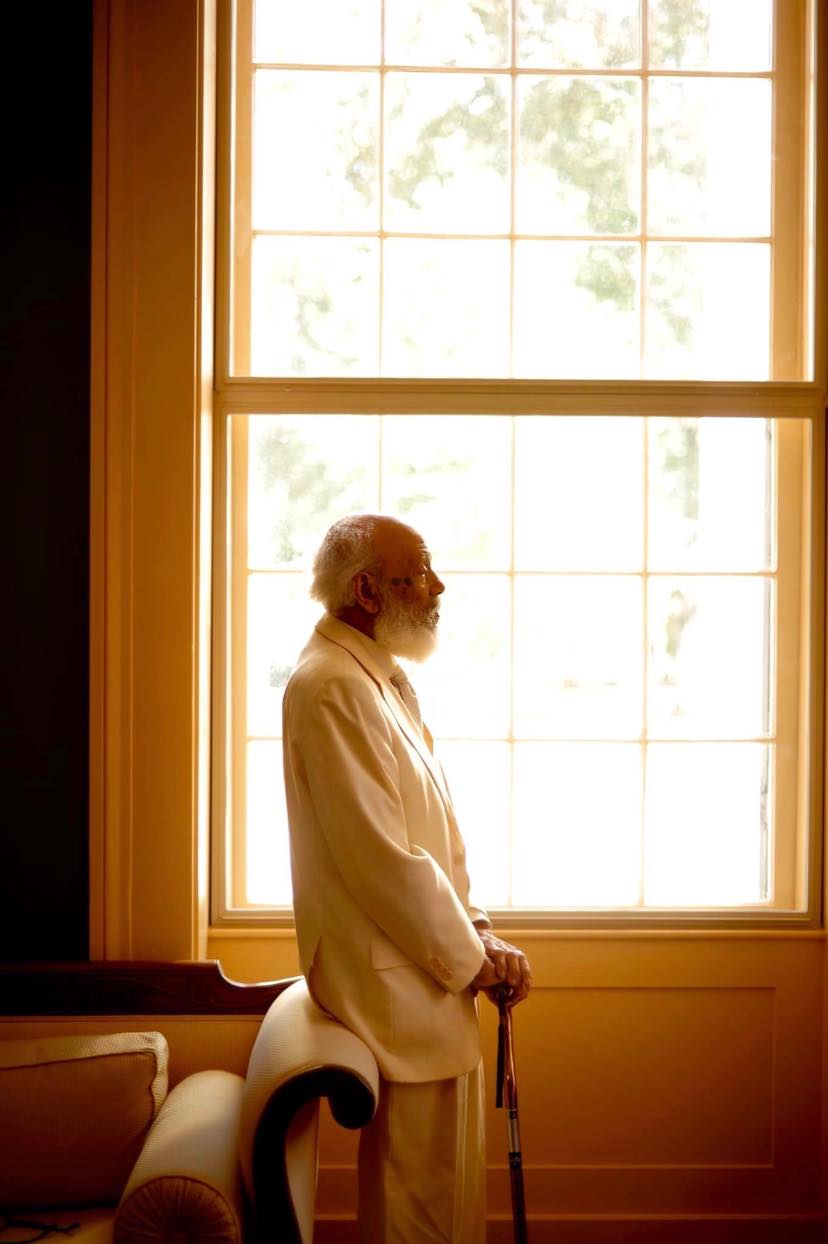

I began this journey 16 years ago as a junior in college merely picking up the camera as a hobby. That small inkling of curiosity has blossomed into a lucrative creative career that yields $25,000-$30,000 a month working just a few hours a week. Although my artistic expression spans many different visual genres, the formula is essentially the same. Natural light. Genuine connections with people. A fundamental understanding of how to amplify the subject in a compelling, enduring, and timeless way.

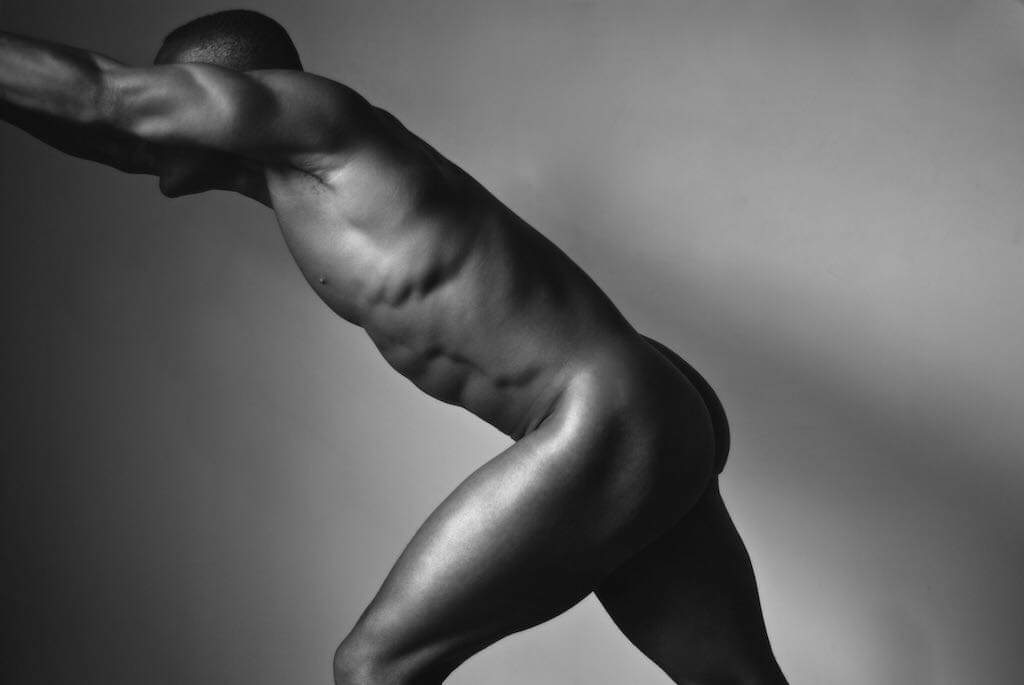

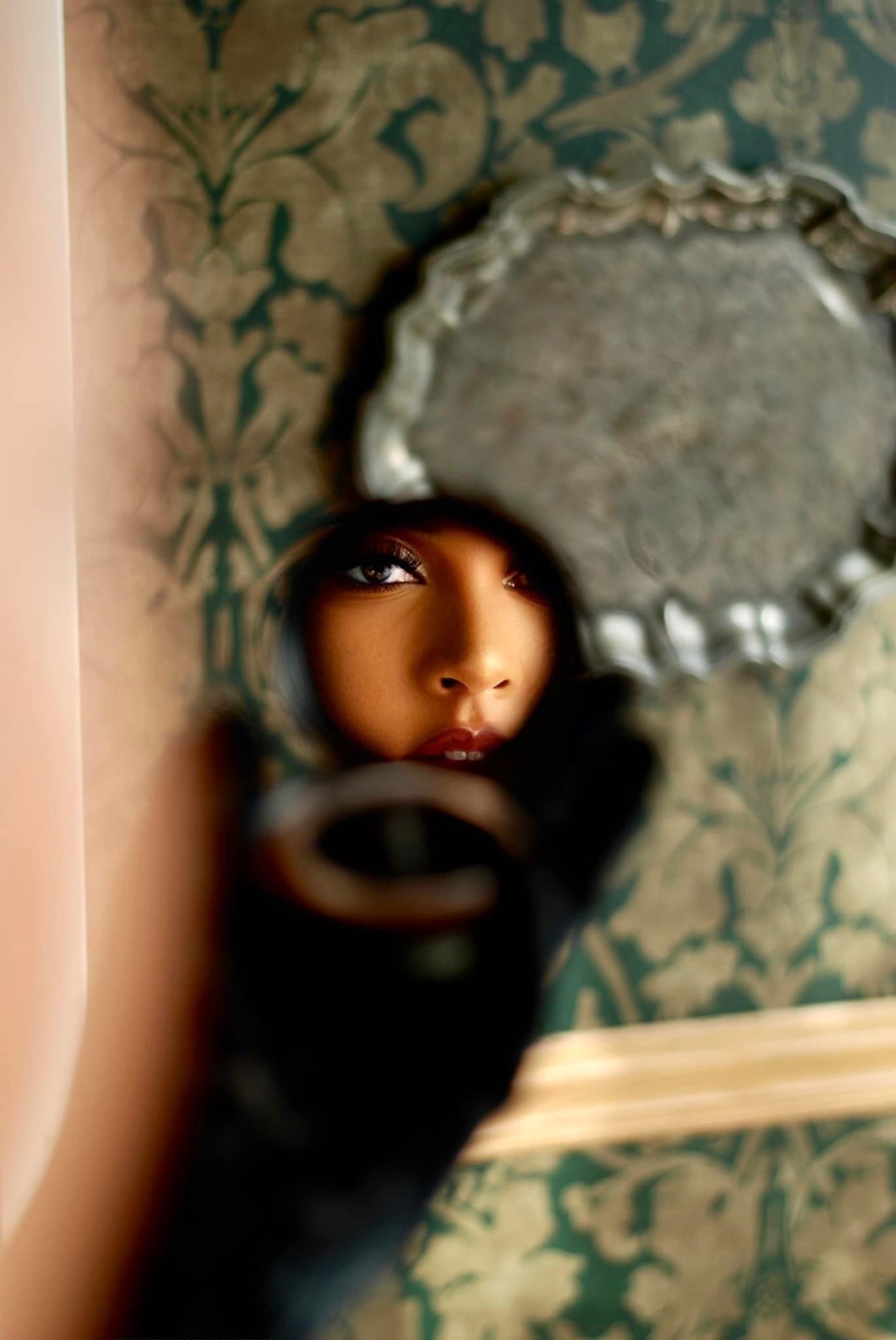

In my professional experience, a lot of photographers are principally concerned with equipment, and the meticulous minutiae around whatever software/platform is currently en vogue. I have set myself apart by deliberately not following trends, and instead investing myself entirely in the subtle art of understanding people, and light, and time. All of the best equipment in the world is wasted if the person or the thing that you are photographing is not honored. Exalted. Magnified.

A big reason that people are drawn to my specific brand of photography is that it highlights otherwise ordinary people/things/experiences in a truly compelling and magnetizing way. I try to tell all burgeoning photographers, and young artists in general: put yourself in your clients shoes. Imagine the nervousness, and the titillation, and the anxiety of being studied, and captured, and critiqued. Once you understand how painfully vulnerable is to have your picture taken, you can develop a language, a humor, and an insight for how to make people feel comfortable when they are in front of your camera. Without that essential degree of emotional intelligence, the exchange will look (and feel) bereft.

Are there any resources you wish you knew about earlier in your creative journey?

In the infancy of my creative career, I was not surrounded by the right kind of people. Creative people needs to be around creative people. But, they also need to be around business people. I am not only an artist, but also an enterprise. If I could go back 16 years, I would have been a lot more pragmatic, and cerebral about the ways in which I conduct business. Invoices. Pricing. Contracts. Per diem. Taxes. Photo archiving. Travel!

I was so caught up in the allure of being a creative that I completely neglected the significance of being business-minded. A lot of people stole from me in the beginning of my professional career. They knew that I was naive when it came to understanding the metrics of business, and they exploited that ignorance. But, I’m not at all unique. Disenfranchising artists is a ubiquitous practice. It is just as imperative that we protect ourselves as it is that we perfect our craft. Hire an accountant. Befriend some attorneys. Develop a partnership with a local art gallery. Ask other artists what they are charging for their work. Ask your competitors what they are charging for their work. Ask the top person in your city, or in your ethos what they are charging for their work. Use that cohesive cachet of information to more adeptly discern how you should evaluate your own time, and expertise.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

This is such an excellent question, and I’m glad it was posed. The customer is not always right. As the artist, you are the gatekeeper. You are the path-forger. You are the architect. When someone comes to you to commission you for your time, and your talent, and your imagination, you have every right to refuse them. If they disrespect you; if they want to underpay you; if they want to second-guess the dimensions of your intelligence. The most important motto I have ever learned in business is this: when it’s right, it’s easy. The right client will not antagonize you. They will not try to destroy the fabric of your joy. They will not look for instances to demean or perturb you. They are only looking for you to perform at your optimal capacity while also characterizing the experience with laughter, harmony, and serious appreciation. For more than a decade, I took the most intolerable people, and I tried to make them wholesome, respectful, thoughtful subjects. But, I’m an artist – not a magician. The moment that you feel any resistance from a client, that is your intuition trying to lead you away from experiences that will result in anxiety, despair, and despondence.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: ArticulatePhotograph

- Facebook: Tenola Plaxico

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/tenola-plaxico-b6030081/