We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Tai Schiavo. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Tai below.

Tai, appreciate you joining us today. Can you tell us about a time that your work has been misunderstood? Why do you think it happened and did any interesting insights emerge from the experience?

All the time, actually. I’ve found that producers and directors tend to label composers as doing a single style after hearing one of their scores, which has led to a lot of funny conversations.

The first time I ever spoke with director Sean Michael Burt, he had heard my score for Dinner Time and was looking for a similar, yet different sound for his upcoming film, Dreamer. He went and listened to my other scores to hear more of my style, but after hearing the rest of my music, when trying to describe my style, he said, “I guess you just write good music” (‘good’ was definitely generous for the music he was referring to back then).

A director who hears my score for Terroir would probably label me as an orchestral composer who scores comedy films, while a producer who hears my score for Dreamer would probably label me as a hardstyle/techno EDM composer who scores psychological thrillers, and I was working on both films at the same time.

I think when you look at a composer doing one specific style, you’re looking at how well they can do their own thing, but when you look at a composer doing various contrasting styles, you’re looking at how well they’ll be able to do your thing. Meaning they’re sourcing inspiration from the film itself as opposed to what they’ve done in the past, which leads to a less generic, more tailored score – and film, ultimately.

I think Ludwig Göransson is a great example of this, with his work ranging from The Mandalorian to Oppenheimer to Black Panther to Creed. He does a ton of wildly different stuff.

I will go ahead and say that there is one style I don’t write in, and that’s documentary sounding music. If I score a documentary, it won’t sound like one.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

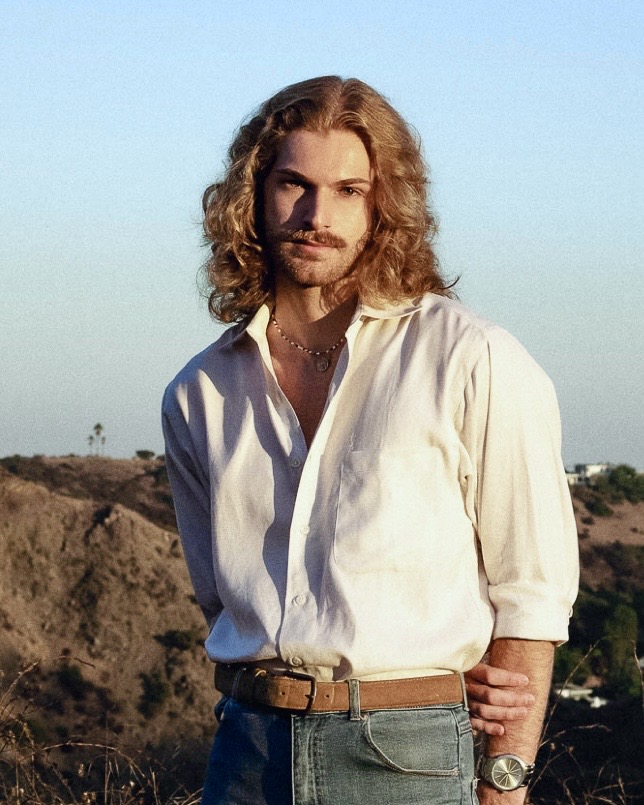

Sure, I’m Tai Schiavo, I got into the film industry through the bathroom window, I provide a range of services, but I’ll just say twenty dollars is twenty dollars, and what sets me apart from others is that I have long, curly, blonde hair and a mustache.

I’m most proud of the fact that every time I go to the dentist, he tells me I’ve done such a great job brushing. I get that feedback consistently. But every time, I push back. I say, Doc, you’ve been telling me that for years. There isn’t anything I could do better? You know, not a single thing I could improve upon? I brush my teeth twice a day, for maybe a total of two minutes – and I floss every night, hand to God. But you, Doc, you brush teeth from nine to five every single day. Please, give me some feedback. So he ends up telling me a specific spot in my mouth that I haven’t hit as hard as other spots, a bind spot so to speak. And I correct it. And each and every time I go to the dentist, he gives me a new blind spot.

I’d like potential clients to know that I’m currently working on my first molar on the upper left side.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

The biggest turning point in my creative life was sparked by a single lesson I had to unlearn, sprung about by a conversation I had with James Newton Howard almost a year ago.

In my last year at Berklee (go Jazz Cats), I went on the annual film scoring industry trip to Los Angeles (I’m still not sure how I was accepted on that trip, there were very limited spots and I was the film scoring class knucklehead of ‘24). On the last day of the trip, we visited James Newton Howard, the composer of many scores including The Dark Knight (in collaboration with Hans Zimmer), The Hunger Games films, and The Sixth Sense – and who dropped out of college to orchestrate for Elton John.

He talked us through some challenging moments in scores he wrote, and happened to casually mention one thing that echoed in my head – he spoke about a moment in a film that had ambiguous emotional implications, and he supported that in the score with what he called a “nebulous harmony.” This implied a choice beyond what harmony to use, to how clearly a harmony should be stated, whether that be by omitting certain notes or adding other notes to pull the sound in uncertain directions.

At the time, I couldn’t believe what he was saying. It was like telling me that beyond choosing what color and style of house you want, you could choose how many walls held it up. The concept he described was like racing half a ferrari with seven wheels.

Before we left, I asked him what on-screen would compel him to write a “nebulous harmony,” and he described the choice of harmonic clarity as regular as the choice of harmony itself. This made it painfully clear to me that I was seeing music in two dimensions when it could be seen in three. It was like I was previously working with harmony in choices of color, darkness, and brightness, and now unlocking the choice of transparency.

The lesson I had to unlearn was that there doesn’t need to be a clear harmony in every moment of music – or even any harmony at all. This realization happened to coincide with a point in my life where I was dissatisfied with my writing on a fundamental level, and inspired me to deconstruct my writing and strip it down to the most foundational component – melody. Since then, I haven’t written a note of music down that I couldn’t first hear clearly in my head.

I’ll cut the story here, but after two painful months of deconstructing and reconstituting my creative process, I began to recognize creative purity so clearly in highly regarded art of all forms. Creativity that didn’t have any logical or theoretical crutches, sprung about directly from the subconscious that speaks to the subconscious. I finally found an answer for why myself and many others are drawn to the music of The Beatles. This is the foundation of what I used to teach my students back when I taught, and what I’d write a book on if words were my thing.

This gave me tremendous insight into the essence of making a film, and how to write music to speak directly with the viewer’s subconscious.

Any resources you can share with us that might be helpful to other creatives?

This’ll sound silly, but I never anticipated how much I’d learn about composing for film from working on a bunch of films.

I thought I had it all figured out in college, as most college kids do I guess – people liked my music and I thought I was ready for Hollywood. As a musician, when you grow up, you study music, and you can get great at that, but writing music for film is an entirely different beast. The music isn’t coming from your mind, it’s coming from the picture. Each film I’ve worked on has taught me several invaluable lessons about filmmaking that I’ll take with me for the rest of my career.

I developed a sensitivity for lighting, and color, and small fleeting expressions of actors, how to handle different shots, bridge scenes, what to emphasize and what to disguise. Learning how to handle different situations on-screen is what I think separates a composer from a film composer.

Don’t get me wrong, I still love all other forms of music dearly, and I think learning the narrative flows of film music can support the music you make in all other areas. For example, I’m currently producing an album for the absolute star, Channing Rion, and we’re designing the flow of the album with a cinematic throughline.

Writing the score for Terroir taught me a ton – it was inherently challenging being a horror/comedy film because all of the horror elements had to fit under the tonal umbrella of the comedy genre, like it couldn’t actually be scary. Aside from tonal genre-nesting, a big thing I learned while writing the score for Terroir was how to write dense suspenseful clusters with specific undertones.

Tying in my answer to your last question, I didn’t just want to consciously choose notes to rub up against each other, I thought that would fail to capture the unique flavor of the suspense in different moments. Instead, I watched the spot in the film over and over again until a single note jumped into my mind. I’d write that note down, then repeat the process until no more notes jumped into my mind. In the end, I was left with a unique cluster chord.

Because I didn’t consciously choose the notes, I allowed what was happening on-screen to enter my subconscious as a feeling, and then present itself to me as a unique combination of notes. This allowed for moments of suspense in the film to be flavored with undertones of a horrific discovery, a comedic fakeout, or a character having a last-second idea.

The most interesting part is that sometimes I’d end up deriving a combination of notes I could label as an existing chord. From then on I never chose a chord, I had to feel it first.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://taischiavo.com

- Instagram: @taischiavo

Image Credits

Cole Nelson