Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Sunyin Zhang. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Alright, Sunyin thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Can you talk to us about a project that’s meant a lot to you?

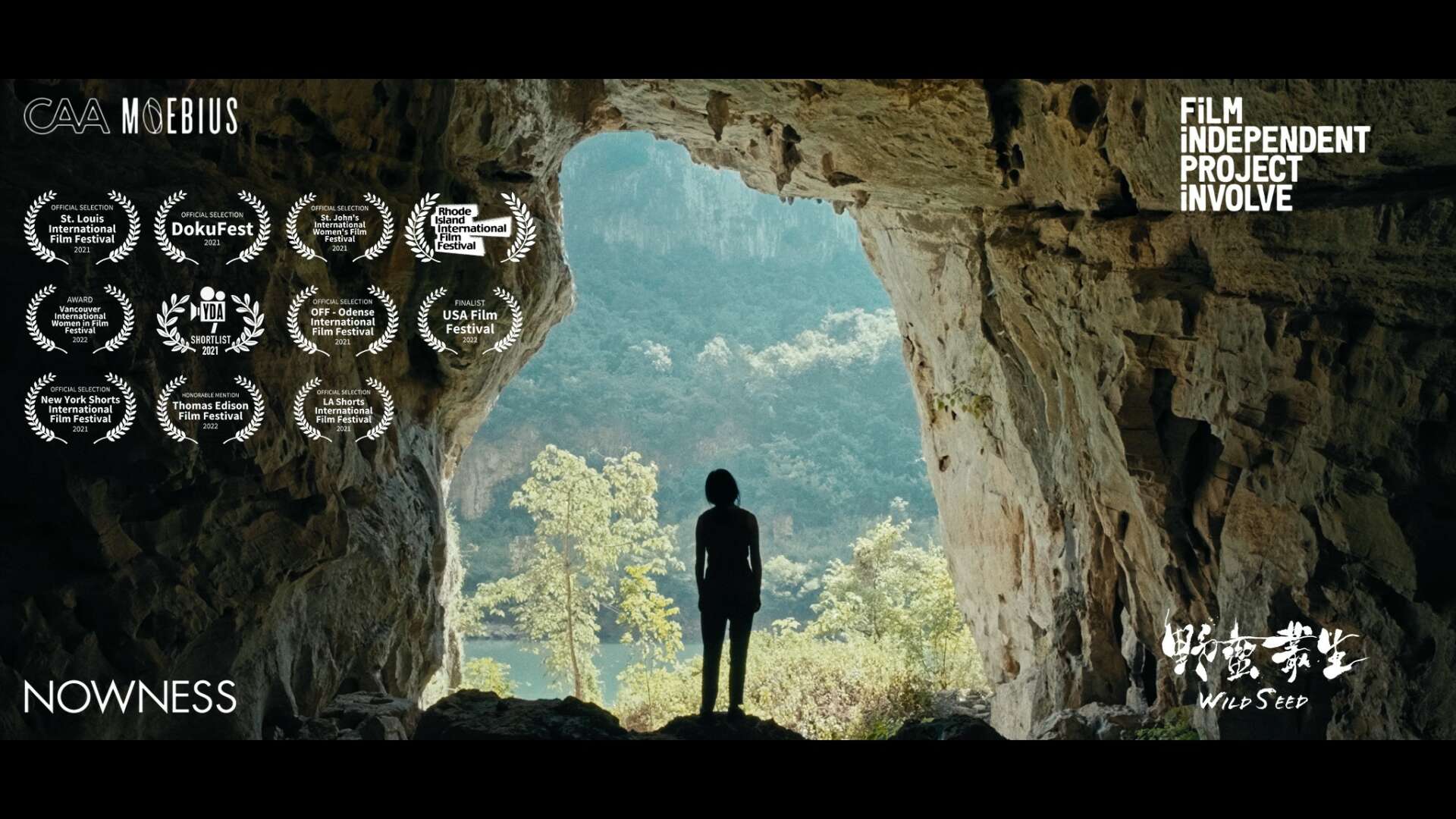

The most meaningful project is my thesis short film, Wild Seed. It constantly encourages me to keep working on my next milestone of independent piece.

Wild Seed was inspired by my family. My grandmother gave birth to three daughters and these three daughters gave birth to three daughters. I am the oldest one. In 2015, China changed its One Child Policy to allow two children per family. Later, my aunt suddenly announced her pregnancy at 43 years old; her first daughter was already an undergraduate. Since that day, all my family’s conversations were about children. But I was puzzled. I guessed that my aunt wanted a son as the goal of her pregnancy. Even today, the tradition in China maintains that only males can carry on the family line. Although her husband and his family insisted on having a son for the past twenty years, my aunt was such a sharp-minded woman. How could she give in and seemingly enjoy this sacrifice? I started to question them and began to self examine why the first thing I thought of was gender issues.

It reminded me of my mother, who had been involved in the One Child Policy as a grassroots civil servant. One day, my mother came back home at 6 am. I woke up and asked her where she went. She said it was an urgent task. There was an illegal pregnant woman discovered in her area of administration. After a few days of watching, the Family Planning committees decided to act. When they broke in at 3 am, the family resisted badly. In this case, they called the police and the government. Upon my mother’s arrival, the woman escaped from the window. Did she die, I asked my mom. No, she didn’t, she ran away. Was she hurt? Maybe not, my mom answered. And why did she jump if she was pregnant? My mom hesitated and told me to prepare for school. I was around 8 years old, too young to understand. Since then, I faced another puzzle. I heard that the illegal family was poor and they had three daughters already. Why did they want more? Did they risk their life just for a son? Women have an unequal social status within the patriarchy and the dictatorship. China’s One Child Policy is obviously involuntary. In order to implement it, most local governments acted violently, and more harshly toward females than males. Women would face extremely tough birth control measures. In 1983, around 21 million babies were born against 14.4 mi 11 ion abortions, 20. 7 mi I lion steriIization operations, and 17.8 million IUD insertions. At the same time, the sex ratio of newborns in China has been severely unbalanced over the past 30 years. Due to gender-selective abortions and the killing of female infants, there are currently about 20 to 40 million “leftover men” in China. Like my mother, my aunt was a policewoman who had been involved in such tasks to arrest those women before. Despite her education and experience, she would still be lost under the pressure of “tradition.” Thus, the power of brainwashing.

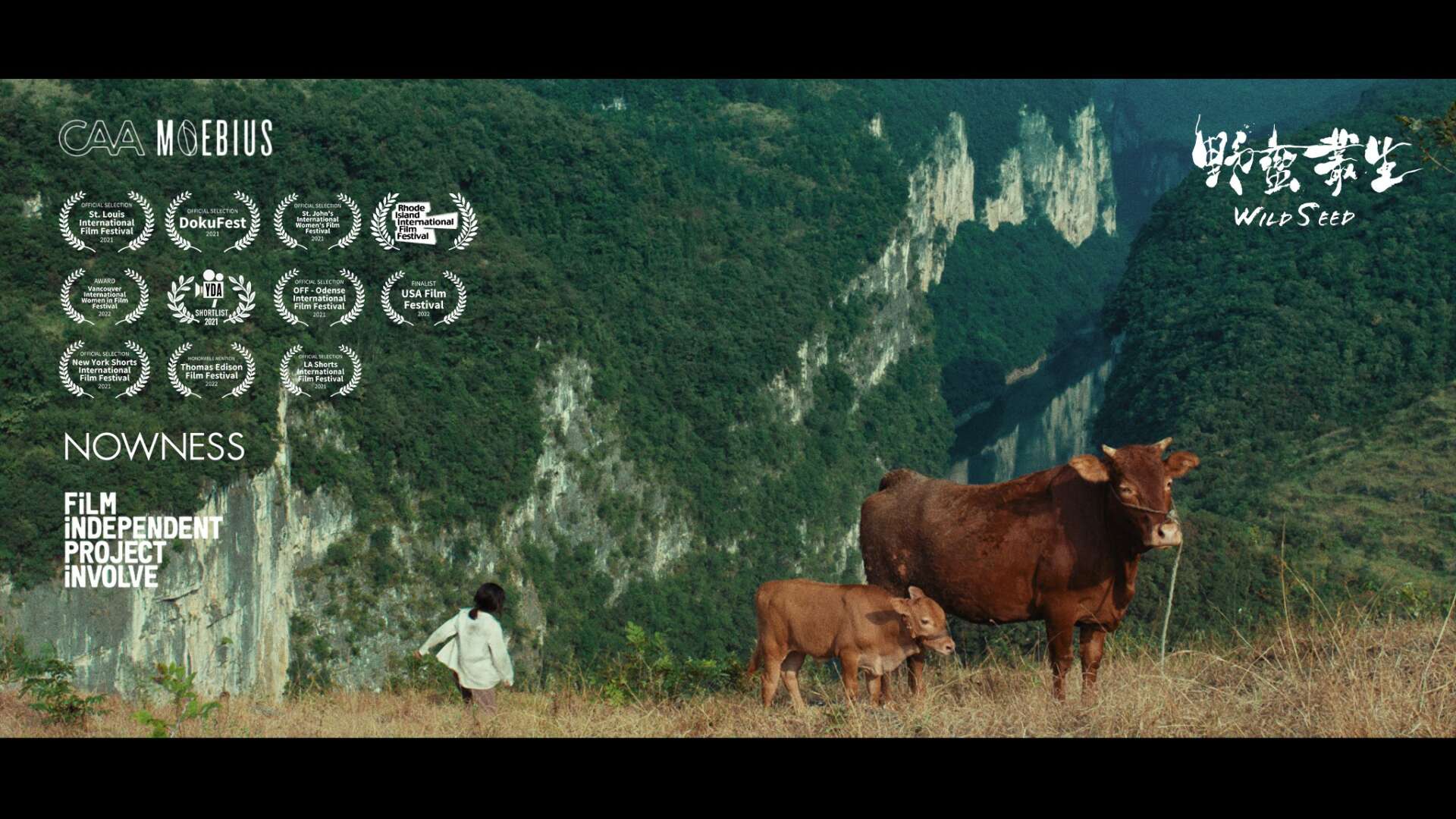

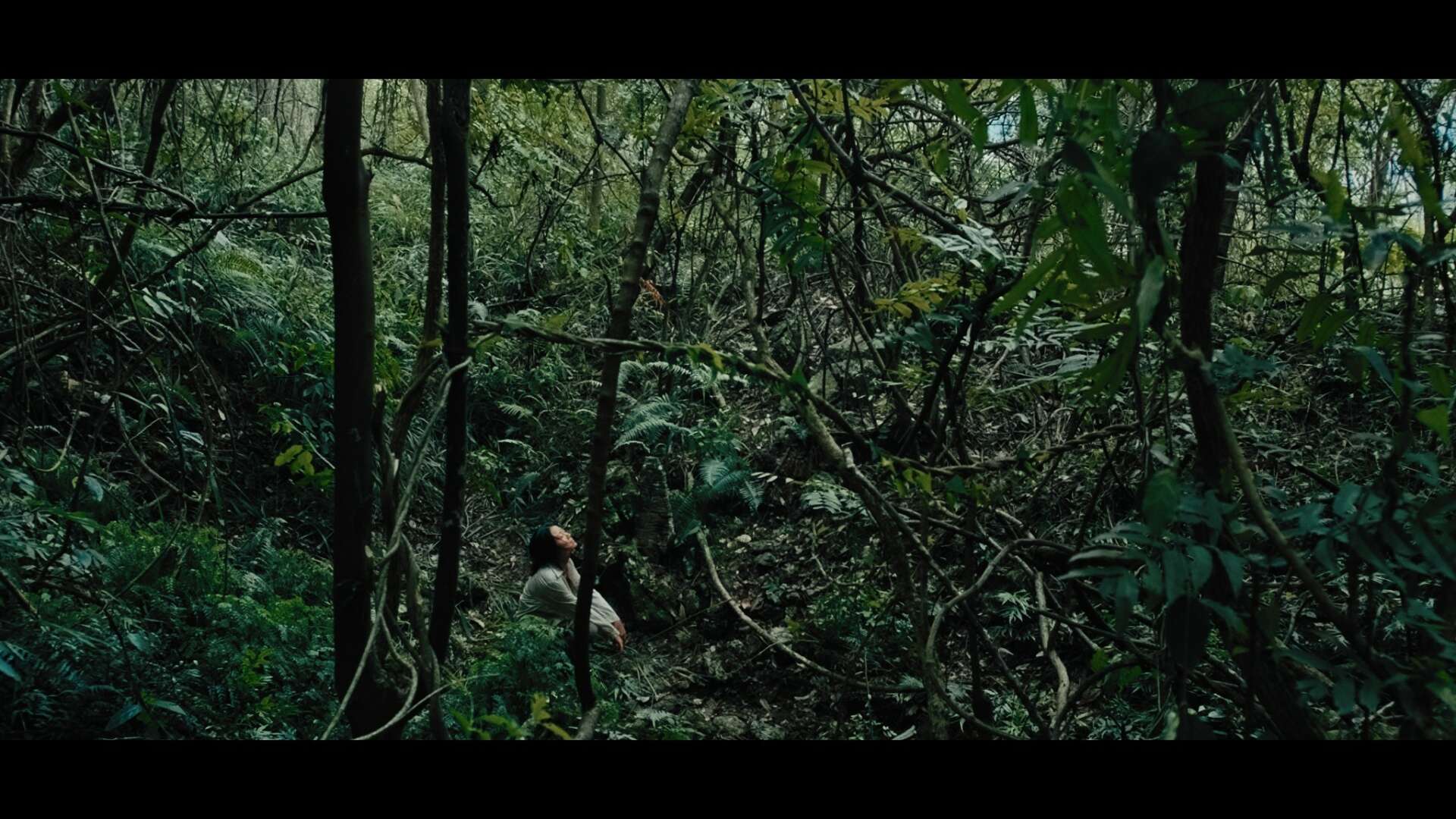

In 2018, I began interviewing. Due to the imbalance of regional development, the history of One Child Policy in Guizhou Province is lacking in records, written or otherwise. The task was made even harder because the local government eliminated the Family Planning Stations in 2015. In addition, they locked related documents. Supported by my mother, I connected with several ex-local Family Planning committees to learn more. Meanwhile, I went back to my uncle’s hometown. There, I met Peng. She was over 70 years old. Around twenty years ago, she and her husband had three daughters. They wanted a son. The government discovered her fourth pregnancy and raided their house. After climbing for five hours, her family had to hide in a cave. According to Peng, her husband worked in the village during the day while she raised a pig and grew corn with their daughters. They encountered monkeys, snakes and other wildlife over the next four years. In the first year, she gave birth to a baby girl who died within a week. Her next pregnancy resulted in another daughter who died shortly after birth. Finally, she had a son. They could return.

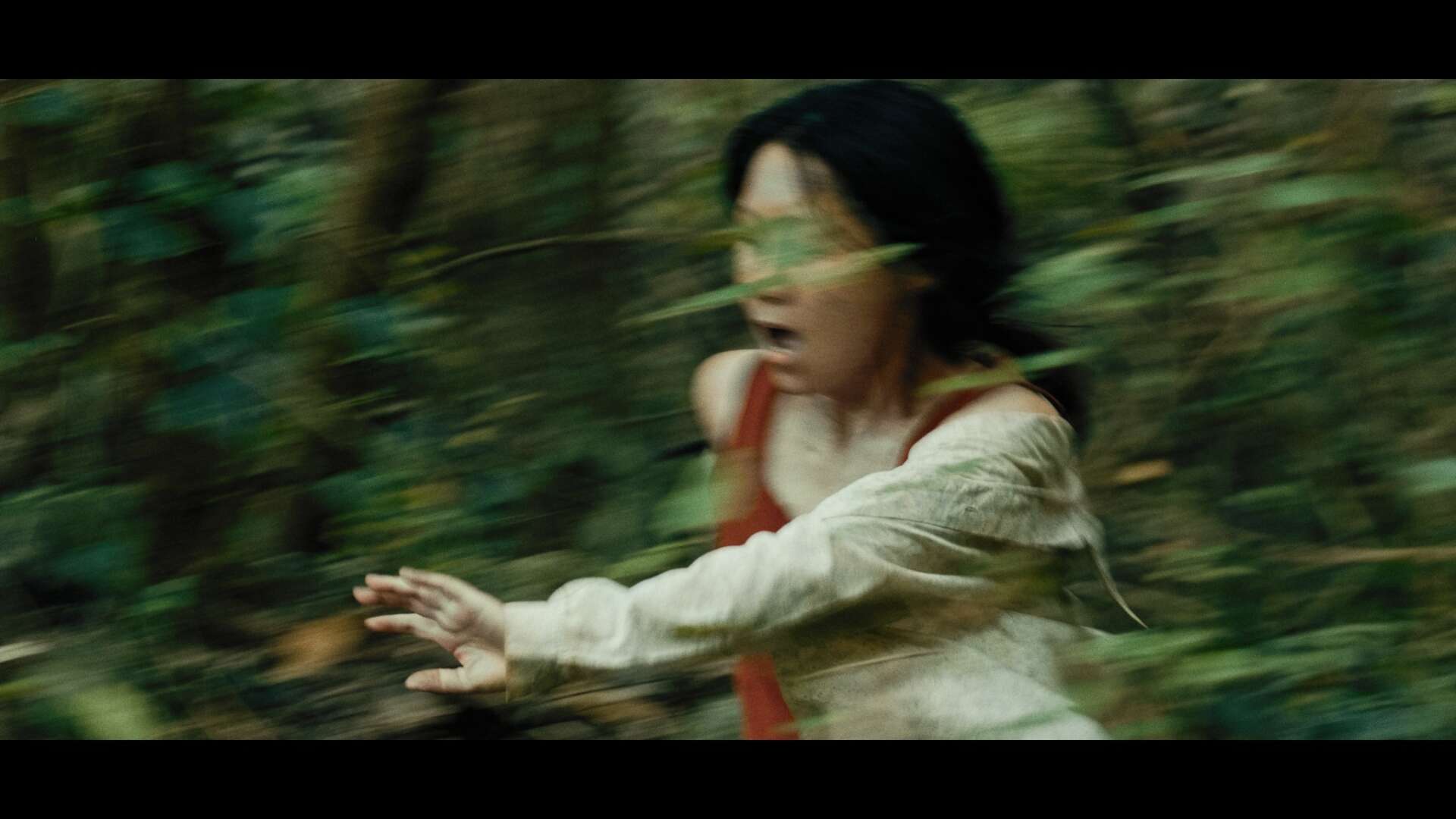

This film expresses my doubts regarding the “Gender Binary,” especially during the period of China’s One Child Policy. Women are brainwashed and oppressed by both the patriarchy and the violent enforcement of the dictatorship. In the interviews, I asked multiple families plenty of times why they insisted on having a son. Most interviewees answered that because it was what it was. Therefore, in this adaptation, I choose not to focus on the journey of great motherhood. Instead, I hope that the audience will be lost in the protagonist’s clumsy and sincere journey of resistance. Her characteristics are non-gender specific. She is tough and reckless and at the same time delicate and sensitive. In order to portray relatively objective reality, I chose naturalism. For cinematography, this film fully depends on natural light and practical light. The terrain of Shaoji Cove is steep without any access roads for vehicles. It takes about three hours of hiking every day so I compressed the crew and equipment. The camera movement covers hand held, still and pan. By using dynamic handheld long takes, it creates intimacy and keeps the audience being with the protagonist. Similarly, the shakiness enhances a more danger and unease situation. While using hand held for reflecting intensive events, still and pan shots can highlight the vivid expression within bold outlines. Meanwhile, I play with hard cut editing to approach documentary aesthetics. Taking advantage of their immediacy, hard cuts and jump cuts become confronting. Based on natural sound, I combine traditional Chinese instruments with experimental electronic sound and I abandon melodic scores to enhance the atmosphere. Overall, the visual and acoustic language present a style that is raw, direct, and fantastic.

Affected by the French New Wave, I believe that the city stands as a plaything. The landscape of Guizhou Province becomes the narrative rooted in the protagonist. As for production design, few props are purchased. The entire cost of props was less than 40 dollars. Basically, we went from one house to another to borrow suitable local items and return them to villagers after wrap. On the one hand, the process of collecting can help me observe the lifestyle and blend in with villagers to prepare for casting. On the other hand, those old items are irreplaceable. They demonstrate the age, regional specialty and authenticity. Except for Tian Xu, the protagonist, other supporting casts are local villagers. Among them, three actors are policemen and one of the three worked as an ex-Family Planning Committee. They are presenting their daily life more than performing. I dislike training my actors to become puppets. I want them truly in the moment so the casting takes a long time. When scouting, I lived in Shaoji Cove for several months to integrate into the lives of the locals. We got acquainted with each other. Because of the trust, they can be relaxed on-set.

Sunyin, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

Sunyin Zhang is a Chinese writer director, producer and editor based in Los Angeles.

Her short film, Wild Seed, is presented by Nowness China, won the the Marlyn Mason Award Grand Prize in Flickers’ Rhode Island International Film Festival, Best Cinematography in a Short Award in Vancouver International Women in Film Festival, Alison Doerner Award for Women Pioneers in Filmmaking, nominated for International Shorts Program Best Short Film in DokuFest, screened at Film Independent Project Involve Showcase, CAA Moebius Showcase, and was selected by over 15 OSCAR qualified and BAFTA qualified Film Festivals.

Zhang participated in Film Independent Project Involve as a director fellow in 2023 and received her MFA in Film Directing Program from CalArts in 2020.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

To be able to collaborate with a bunch of great crews and to aim for one goal is the most purest process for me as a filmmaker and an artist. We learn from each other and support each other, we stay flexible to every moment and live in the moment, we share the same expression no matter how vulnerable and personal it is. When growing up, I’m experiencing the most common problem for every filmmaker, which is how to balance your financial independence and your dream. That unique process of filmmaking still encourages me to stay humble and keeps learning during my hard time.

Any resources you can share with us that might be helpful to other creatives?

Art is a very selfish way of expressing your own point of view. It is just as simple as if you don’t want to lock your door today. But it is also as hard as if you find out your home is being burglarized at night. Once you know the risk, then just go for your wants.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.ioooilab.com

- Instagram: sunyin.z

- Linkedin: Sunyin Zhang

- Other: Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/user60820750

Image Credits

Producer, Writer Director: Sunyin Zhang Director of Cinematography: Ai Chung Colorist: Haobo Wang