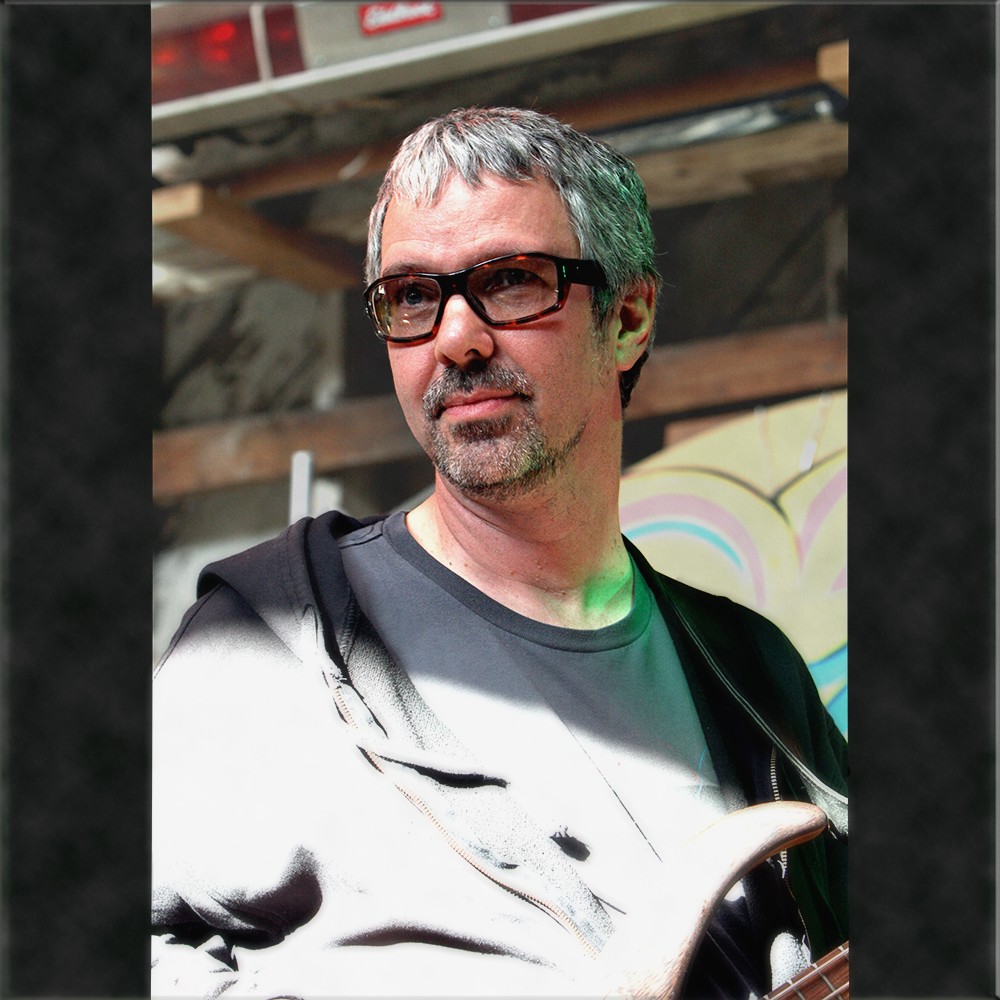

We were lucky to catch up with Steve Turnidge recently and have shared our conversation below.

Steve, appreciate you joining us today. We’d love to hear about when you first realized that you wanted to pursue a creative path professionally.

After working at a few companies for a total of 25 years, a bubble burst and I was looking for work.

My friends were on unemployment (which I had never tried). In looking at the requirements to qualify, it seemed to be much more work looking for work (for someone else) than if I just took all the skills and heart’s desires and put (at least) forty hours a week into building my own business.

I gathered together the things I enjoy doing, and offered these services to friends and others via word of mouth.

I had this feeling once before when I had changed careers – I was at the top of my company, and the next rung wasn’t very creative there. On a drive home, I realized I was in a rut – a grave with the ends kicked out.

Just outside the rut is the minefield, When you try to escape the rut – something blows up that makes you want to dive back in. If you make it through the minefield, you reach the promised land… and for me, that was a shift into a very creative life.

Steve, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

My story starts as a teenage electronics assembler working on depth sounders (fish finders) for the marine industry. This is what I was doing as a day job while waiting to be a rock star. After several years of this repetitive assembly work into my mid-twenties, I realized that rock stardom was becoming increasingly unlikely.

While watching circuit board after circuit board go by on the assembly line, I realized I’d prefer to be the one that designed the circuit traces on the boards rather than stuffing components into them, which is the domain of electronics drafting. The kicker for me was that drafters did not have to be able to draw straight lines or perfect circles freehand; they had T squares and other drafting tools for that.

Drafting work was generally dry and clean, and you could do a task once and leave it behind—and the drafters always seemed to be able to arrive at work later than we had to in production. Rock-star hours were just as attractive then!

In the early 1980s, I saw pro-audio company Rane Corporation’s very first demonstration of their new product line at a local music store. They presented their products as being inspired by philosophy, and the products all had interrelated design. There was a six-channel amp, a twelve-in, six-out matrix mixer, and a six-channel headphone amp. These were very forward looking, high-quality products at the time.

Their philosophical bent and clever product design were right up my alley and inspired me to want to work with them, and to work in the pro-audio world. I spoke with a couple of the owners after the presentation, asking if they had an assembly position available, and they invited me to interview. At that time they were newly founded and working out of a single warehouse bay. Unfortunately, they had nothing to offer me.

This experience with Rane Corporation ignited the consideration to follow my heart’s desire and start up my own pro-audio company (which finally happened when I founded Synthwerks in 2009, around twenty-five years later). To rise to the required skill set for this vision, I would need some education in a specific vocation. I chose electronics drafting to be my professional career, and took a class from Lake Washington Vocational Technical Institute, completing a year-long course in eight months.

Soon after I completed the drafting course, my instructor phoned me at work (where I had moved up from being an assembler to a quality-control inspector) asking if I’d ever heard of Rane Corporation. It turned out that the five original owners of Rane had been doing their own production-level day jobs in addition to their management and ownership roles and responsibilities. The company had finally grown enough to allow each owner to hire an assistant to handle his or her day job so he or she could focus on management.

After being “just about” too enthusiastic about getting a job at Rane, it turned out that much was just right.

It was a great job, and I was learning every day. Going into an environment that feeds you the raw materials of what you are most interested in is an amazing experience. My first day, they had just finished laying out their most complicated circuit board to date, a digital delay, and the Mylar films were colorful and filled with little pieces of tape. My first job was to “check” that design. I had no idea what I was doing…

During my initial three-month performance review at Rane, I was given a single critique: that I asked too many questions. This was a surprise, since the questions I asked consisted mainly of “What should I do?”

From that point on, I gained the attribute of “See what needs doing, and do it,” and put that into action every day. That one performance review was probably the most significant turning point of my career. At Rane I followed a path from electronics drafting and becoming expert at (a very early version of) AutoCAD, and moved into making the product cosmetics.

I was able to use AutoCAD to define the product panel art that previously had been graphically laid out using physical preprinted lines and text, cut out, pasted and photographed on white poster board to create the films for the silk-screen process. We created a new process to generate the product artwork using lines in AutoCAD instead. This involved drawing each line thickness in a different layer, and having each layer photo-plotted separately on a single piece of film that the silkscreen department made their screens from.

Over the eleven years I was at Rane, I moved on to networking the company and becoming a certified telephone technician and installing a phone system. My final job there was as Systems Manager.

At Rane, I made good use of the engineering library to find out as much as I could about audio mastering. The books would be very detailed up to the point of sending a song to a mastering engineer, and then again what to do when the song came back, but very little about actually mastering.

I asked a knowledgeable friend about mastering, who pointed me to a brand new plug-in at the time to describe what mastering was. That started my mastering career – seeing that this plug-in really didn’t do the job, I worked out my own system of mastering with a computer (in the box).

From Rane Corporation, I moved on to Digital Harmony – an engineering company that was first to put audio onto FireWire. When Digital Harmony crashed in the tech bubble, I went on to teach a year of audio recording at Shoreline Community College in Seattle. The best way to learn something for real is to teach it! That experience put concrete in my audio foundations.

After the audio class, I went solo – mastering and designing circuit boards for the audio industry. I also took my learning about what audio mastering is and wrote a couple of books about it. Desktop Mastering; which is about the nuts and bolts of mastering in the box, and Beyond Mastering; physics and philosophy for the mastering engineer.

Since I went out on my own, I’ve found The Universe makes the set list – and if I were to retire, I’d do the same things I’m doing now, so it is as if I am retired – no need to worry! I get to put my passions into actions every day.

How did you build your audience on social media?

Utilize the constellation of social networks – find out where your readers and market hang out and create a presence there. For that matter, create a presence on as many sites as you are comfortable with maintaining.

The key to this is to have a master collateral store of your bio, pictures and “metadata” style information – everything that you need to set up an account/page at any given social networking site. Think of each site as a copy of your book, placed where people congregate. In this way you can be everywhere all the time. Your master collateral store can also be your personal webpage…

The setup is just the beginning; make sure you have the site set to email you comments made on your page so you can monitor them. The next key is to use each service at their “sharp end” (like a pencil). For instance, LinkedIn is great for business relationships – only connect to those you would like to have refer you or that you would refer. Facebook is the stage your life is played out on – connect here with those you wish to have and interact with in your life. In addition, create a Facebook Artist page for your general public interactions.

There are and will be more focused sites as well for books and publishing, feel free to add those to your constellation, but be careful of the echo chamber syndrome. Best to address the audience where they live…

Clients can be found in a number of ways. The key is to listen for work, not look for work. Don’t be shy; make yourself known. For instance, I keep track of my musician friends album progress – when I see their mix is done and are about to go to mastering, I reach out and offer my services.

Use inanimate agents such as business cards to promote your work for you when you’re not around. Be a light in your community – join the local associations and societies: The Audio Engineering Society and The Producers and Engineers Wing of the Recording Academy are great opportunities to interact with people that can use your help (in the audio domain). Other trades have their own associations – find out and participate with your local chapter or section. If these societies don’t exist in your area, contact them to set up an official presence in your town.

Social media is a less tangible instance of meeting live in person, but it has a much greater time reach. The key is to post what you love, especially scientific and topical breakthroughs that others may not have discovered yet. This makes your presence must see and ensures repeat visits.

I chose Facebook after leaving Myspace in 2008. I have accounts on most of the rest of the services, but focus on Facebook, as I have close to 5000 friends there. I keep being challenged by the 5000 limit as when I go through my friends list I know and have personal connections to most of the people there. The connections were gathered largely through real world meetings over the years.

I spend several hours a day combing through my email and data cascades for relevant items to share – I’d be doing this anyway, so it gives me an additional reason (and justification) to be consumed by email daily.

Usually, I keep personal issues at a minimum – at least I did prior to the pandemic. I found it useful during the depths of our shared experience to regularly go outside to our deck, take a picture of the backyard, and write about what I was going through, and sharing coping mechanisms… This turned into 97 essays that collectively are called Beyond Pandemic. A form of writing in plain sight – and the problems I was going through were shared by most of my friend list.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

There are new tools available to us these days that will only get more useful and resilient, primarily around the idea of decentralization. Blockchain and AI are currently primitive examples of these tools.

Our current state of the art is following the path that electricity and electronics followed a century ago. In the early 1920s the state of the electrical arts focused on lead-acid batteries. The knowledge of what electricity actually was was hidden from view – Hawkin’s Electrical Guide likened electricity to the “luminiferous ether,” but higher level functions had to wait until the midcentury inventions of the transistor and microprocessors to usher in the modern age.

AI and Blockchain (and future manipulations of these) provide “electricity for information” – when we evolve these technologies (and accept that they are primitive at the moment), we’ll be able to set up dynamic smart contracts and interactions where artists and creatives automatically are compensated for their work at the time and place of transaction.

We can devise “bundles of functionality” whose components do not exist yet, but there is a place for them – like if users of lead-acid batteries started writing code with the future in mind. New tools are appearing every day – staying aware of what will be possible gives us landmarks to look for, as new horizons are crossed.

The thing about decentralization, everyone has their own idea of what it is – and that’s a good thing. The point of it, really. We are used to learning things we can conceive of and get our minds around – decentralization is not like that.

The atmosphere is a good example of decentralization. Conversations happen in the air, but not all conversations are related. If someone asked you what conversation is happening in this air — you couldn’t answer with certainty. No one controls the use of the air for speech. We can be in different parts of the world speaking together, and still be communicating (think Zoom). If you can dictate or specify the content of what happens in a given domain, that domain is centralized.

Decentralization provides a method of assembling functions and processes rather than exposing ourselves to the risk of the innovator’s dilemma, where the first creator of a product can be overtaken by imitators without the investment of time and resources into research and development. We can distribute process, not product, generating standards that anyone can use and improve upon.

As society realizes we are all components of a single entity (the global consciousness), a shift will occur allowing each person to find the expression of their heart’s desire that is their calling and job.

We are in post-scarcity – where anything you can think of has already been created. Now, we choose components for functionality rather than design and make them. As these functions are specified, we can find better fits for the specification and make the bundle better.

For instance, when cars were designed, all the components were specified – wheels, engines, chassis, controls. The first examples of these were primitive – wheels made of wood, which broke down inconveniently. At some point rubber tires were implemented and the whole system improved.

x

Contact Info:

- Website: http://www.arsdivina.com/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/arsdivina/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/arsdivina/

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/arsdivina

- Other: https://www.pinterest.com/arsdivina/mastering-work/