We recently connected with Stephanie Garrett and have shared our conversation below.

Stephanie, appreciate you joining us today. We’d love to hear about a project that you’ve worked on that’s meant a lot to you.

I’ve been really fortunate to work on many meaningful projects in my time in theater. Part of that was having a tremendous undergraduate experience at the Gainesville Theater Alliance, where one of the first shows I worked on was a production of Ragtime, a beautiful musical that tells the story of racial, gender, and social struggles in America at the turn of the century. I’ve always been interested in the stories of minorities, especially women, racial and ethnic minorities, and the LGBT+ communities. Musical theater is one of my favorite performance genres, and it has a long and interesting history that intersects with Queer and minority communities since its origin as an American art form. Consequently, it’s a fantastic medium for exploring important but overlooked perspectives.

I think the most meaningful production I’ve worked on in recent years is Into the Woods. In 2022, I was serving as the Artistic Director for the Holly, and I chose Into the Woods as the season opener. It’s one of my favorite shows, and one that I had long wanted to stage in a specific way.

With Into the Woods, one of the things that was most important to me was to emphasize the danger of a patriarchal reading of the musical (something that many people, including actors themselves, don’t question). For example, many people don’t realize that the Wolf’s interaction with Little Red is meant to be a very clear example of a sexually predatory relationship. (It’s quite obvious in the original production and in most professional productions, but in smaller communities many directors avoid the subtext. I don’t blame them; it’s terribly uncomfortable.) Likewise, many people will unthinkingly label the Baker’s wife as sexually promiscuous and judge her for the “affair” she has with the Prince in Act Two. What they won’t do is equally blame the Prince for that encounter, even though he’s as promiscuous as the Wife (more, in fact). Somehow, the Wife is supposed to be the gatekeeper for both their libidos. But my main quibble with the way the story has been told (even in the original production) is that the Baker’s Wife refuses the encounter with the Prince…several times…and no one ever seems to remember that. Her “no” gets buried and forgotten because we (the audience) know that she’s attracted to the Prince, but it’s terribly important to remember — to be alert to the fact as it’s happening — that she’s saying “no” to him, and that he’s not listening. It bothers me that audiences and actors regularly don’t acknowledge this. I don’t think they are even aware of it.

It was, therefore, important to me and to our cast that we tell the stories of all the characters, but especially the women, in the right context, and that we treat them with sympathy and compassion so that we could bring attention to those moments that everyone somehow seems to forget. Women’s stories are so often overlooked, especially when they deal with consent. I think that “Just A Moment” is the Act Two counterpoint to “Hello, Little Girl”; they demonstrate the life-long struggle women often experience concerning their sexual agency and consent within a patriarchal society. (And, of course, women are not the only ones who struggle!)

Into the Woods is often portrayed as a story about the difficulties of parenthood (especially fatherhood), and that’s an important story to tell, but it’s just as much about the female struggle to find a agency in a world that wants us to be a very certain way if we want a voice. (Cinderella — the only young woman who is the right age, right appearance — has the most political power of all the women in the show, and the Witch, while she has power independent of her appearance and age, is universally distrusted and disliked by everyone).

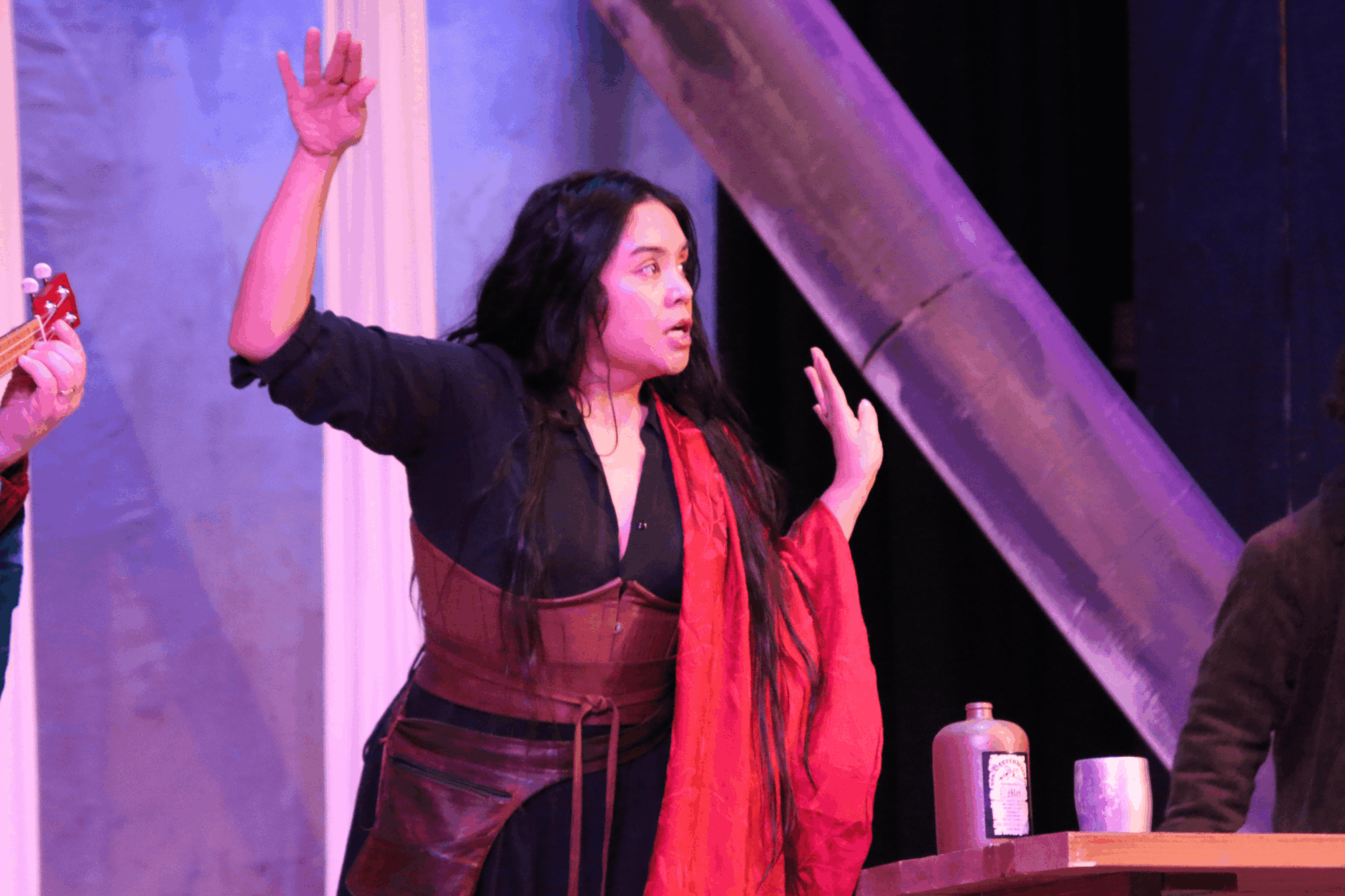

I wanted to highlight the reality of what was happening in the story, to make it more difficult for audiences to ignore the problems the female characters, in particular, were facing. As I worked with my wonderful and diverse cast, we developed connections from our own experiences to create a more realistic approach to the stories in the show. Our Cinderella wasn’t just struggling with indecision; she was also struggling with her sexuality. Our Little Red was confident in overcoming what had happened to her, not just confused or flippant about it. Our Witch and Jack’s Mother were coming to terms with aging and parenthood from a uniquely single-mother perspective. Our Baker’s Wife was struggling against the confinement of motherhood, the frustrations of a difficult marriage, and her own sexual desires and needs.

In order to help the audience stay rooted in the reality of these characters, I designed the show with modern costuming and imagery. For example, the Wolf was dressed as a drab, ordinary everyman because “wolves” (predators) don’t advertise their intentions with claws and teeth in the real world. His performance — fluctuating from meek when anyone was looking to feral when we were hearing his internal voice — was far more disturbing (as it should be) than a wolf costume would have allowed. Likewise, seeing Cinderella in ill-fitting hand-me-downs, Little Red in a punk outfit, and the Baker’s Wife in contemporary clothing helped us connect with them more personally. The set was the attic of an old house, where long-abandoned objects became all the fantasy elements we needed.

It was a great privilege to work on a show like this, and I found it very meaningful on many levels.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I have always been passionate about theater, directing, and designing, since I was a young child. After devoting myself to theater throughout my early years, I trained in design, directing, and leadership at Brenau University (B.A. Theater) through the Gainesville Theater Alliance, an award-winning and nationally recognized program. I then worked at Florida Studio Theater (Sarasota, FL), one of the most successful regional professional theaters in the country. FST specializes in producing new plays and pushing boundaries in its community, and I learned a great deal during my short time there. I went to grad school at the University of Georgia (M.A. English), where I concentrated on research in the long nineteenth century, specifically female playwrights. I then taught at Emmanuel University (Royston, Ga), chairing the Theater Arts Committee and directing and designing productions. When I moved back home, I started volunteering at the Holly Theater, where I had learned so much as a child, and eventually became the Artistic Director. I recently retired from that position, but still direct and design. I’ve written and produced plays, coached actors, taught classes in acting, directed adult and children’s productions, professionally choreographed, and designed sets and costumes for multiple productions. Julie Taymor is the director I admire most in terms of style and approach. My brand is finding unique ways to stage classics; adapting classics for the stage in fresh ways; and telling the stories that need attention.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can provide some insight – you never know who might benefit from the enlightenment.

If I could share one insight with non-creatives (and I believe that everyone is a creative, deep-down), it would be that it’s important to understand boundaries in the non-creative/creative relationship. Often, especially when working within an organization, “non-creatives” have to work alongside creatives to get the job done. We don’t all have the same abilities or gifts, or training. Ultimately, we all want to be aware of our limitations and strengths, and use that knowledge to work together. But I have experienced challenges in working with “non-creatives” in the past when it comes to trying to explain the creative process and the needs of productions or projects in a way that makes sense to them. For example, when I hear that another theater is popping up near ours, I’m excited. Another theater means another group of artists with whom to collaborate. It means more talented people will be attracted to our area. I feel that way because I understand that art and creative endeavors are ultimately all about collaboration. When one theater is successful, all theaters are successful because artists help each other. Art isn’t really competitive; it’s collaborative. But it’s often very hard to explain that non-competitive position to people in business, for example, or who are used to dealing with corporations, where competition is a given. Arts organizations might attract the same audiences, but their “brands” are different, and audiences can come to more than one show at more than one theater. We certainly don’t want our patrons only coming to see us! We serve our community, but part of that services is encouraging them to see good productions at other places as well. We want the arts to flourish, and we’re part of that process. It isn’t always easy to communicate this important idea to others who are more used to seeing any other similar institution or organization as competition. But creatives know that each of us fulfills a unique niche that no other artist (no matter how gifted) can fill.

What can society do to ensure an environment that’s helpful to artists and creatives?

I think the best thing our society can do is to learn to appreciate creatives, artists, creativity, and art. When we fully appreciate these things (by learning enough about the process that we understand how difficult it is to do), then I think all the rest will follow. I think the main obstacle to creating support for the arts and creativity is that many people don’t understand what art is in the first place or how it’s accomplished. Working at a community theater is a fantastic place to see that lesson play out over and over. When a lawyer, doctor, pharmacist, politician, nurse, construction manager, business owner, or chef (and we’ve had all of the above) walks into our theater, auditions for a show, is cast, and starts working through the process, they tend to come out the other end with a whole new appreciation for what theater actually is like. Most people just don’t know what they don’t know, and creativity always looks a lot easier from the outside.

There are many ways we can foster appreciation for the arts, but the main one that I’ve seen work well is getting people involved in the process itself, on some level, either by letting them be a part of it (the earlier the better — I’m looking at you, Education and kids programs) or demonstrating in a memorable way how the process is done (a la, well-made social media).