We recently connected with Sophia Karina English and have shared our conversation below.

Sophia , thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. What’s been one of the most interesting investments you’ve made – and did you win or lose? (Note, these responses are only intended as entertainment and shouldn’t be construed as investment advice)

The worst investments I’ve ever made were when I wanted get the most expensive gear to learn a new craft or skill. I think craft is perceived as being a bunch of hobbies meant for older white women with disposable income, so the tools for craft tend to be pretty over priced. But ultimately most art forms can be at least learned without any fancy equipment. I’ve gotten overexcited more than once when learning something new and will spend so much unnecessary money for something that I don’t end up pursuing long term. If I could give advice to avoid this, it’d be to go on YouTube and see what work arounds experienced craftspeople are using to avoid some of this overpriced none sense. Learn cheap! As cheap as you can. And then, after you know that you want to invest in some quality equipment, go and make the big fancy purchases. The best investments I’ve ever made are a $20 metal bead loom, a $5 crochet hook that I put some bees wax on the tip of to pick up beads with, and experimenting with different adhesives to find what worked best for me. The adhesive thing probably cost me about $50 over the course of a year of trial and error. All three of those tools are still in my tool kit today and are what I use on a daily basis.

Sophia , before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

Well, my name is Sophia Karina English. I was born and raised in San Francisco, California, in between the outer sunset and mission district. I’m a crafts person and artist based in Chicago. My skill set and interests are pretty varied, but my focus is in beadwork. It feels like a lot of coincidence has brought me into the corner of the craft/art world that I now find myself. I always thought I would be an illustrator, maybe even work in animation or comics one day, but when I started taking art seriously as a career, something wasn’t clicking for me. So when I started at an actual art school, I was sampling anything I found even a little bit of interest in.

Eventually, I found my way into SAIC’s fiber arts and material studies department. There I was introduced to bead weaving, specifically Latin American bead work as a method of visual storytelling. I’m Nicaraguense myself, and I think I found beadwork at a time when I was really struggling to find where my ethnic identity could be represented in my art. From an American perspective, Nicaragua doesn’t have a strong cultural or artistic identity, and because of that, there’s not a lot of strong research about their craft history in American academia. It always bugged the hell out of me that I was in all of this debt at this fancy art school with some of the best resources in the country at my disposal and still couldn’t find any good information about what I was interested in.

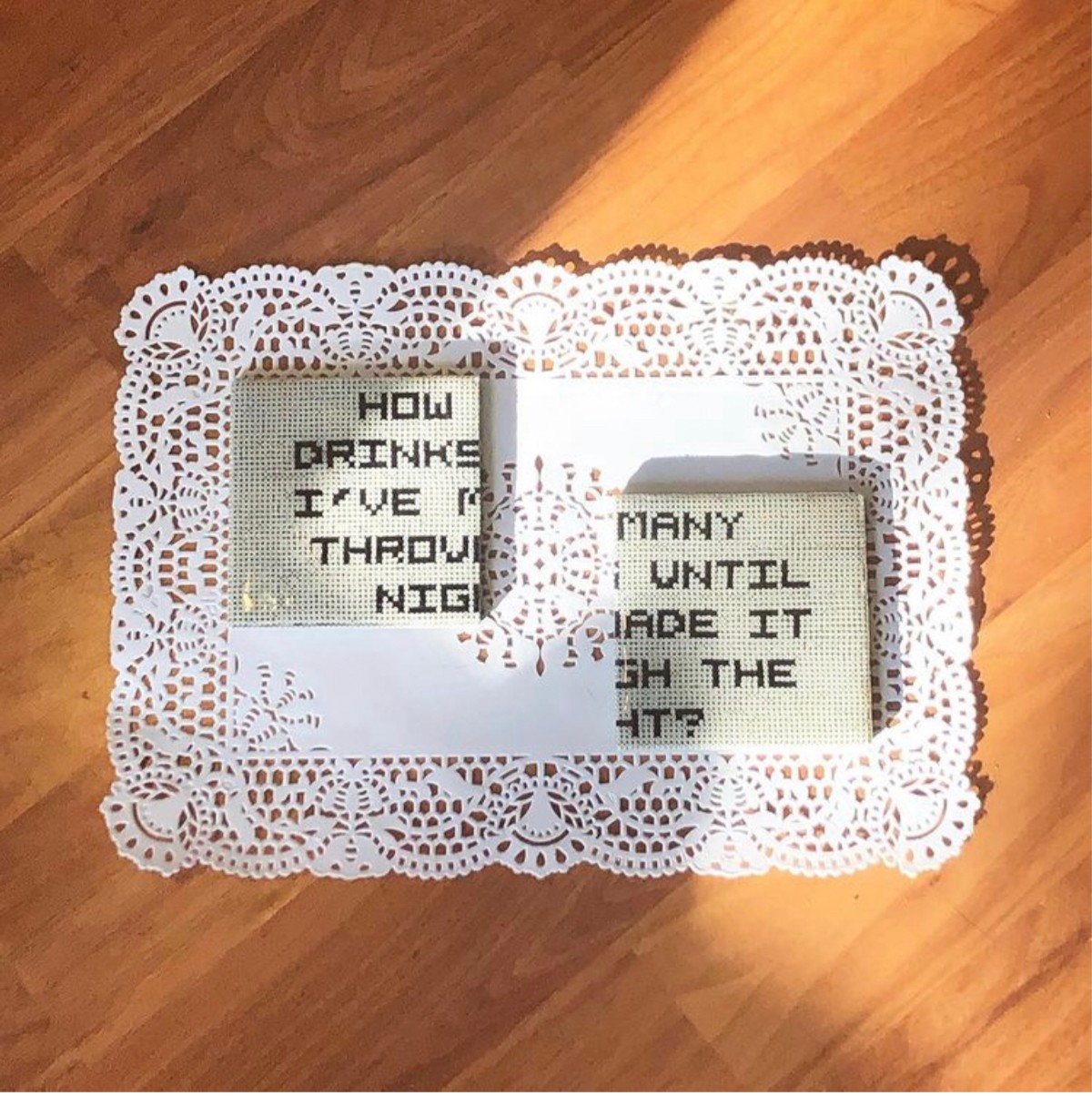

I found one article about a cream-colored beaded textile from an American archeology student in Nicaragua, no proper dating or understanding about what culture it had come from or what it was used for. Just that it had been found, and that it was cream colored. The realization that no one was coming to hand me this information on a conveniently English-translated silver platter put me in a position with a lot of passion for this craft, a lot of questions, and not a lot else. So I started beading the questions, in the same off-white palette as that original textile. I kept my aesthetics simple and muted because the questions and statements felt so simple. My very first beaded piece, an earring that runs the length of my body and reads “I don’t remember agreeing to any of this,” felt like a small gesture at first, but the satisfaction of how easy it was to convey the statement surprised me. This feeling is what encouraged me to make what is now becoming a strong body of work and a small beaded jewelry practice.

I’m immensely proud of how far my craftsmanship has come and of all the trial and error in contemporary art and jewelry design that has helped me find my own aesthetics and passions. If there was anything I wanted anyone to know about my practice, it is that it’s all an open letter to myself, my family, and my community.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

On a societal level, it’s truly all about respect and time. Artists need more support in every regard and for institutions to take us seriously enough to offer that support in a serious manner. Nothing exhausts me more as an artist than receiving an offer for a show or a residency only to then find out that I’m also being asked to do the work of multiple administrators. The best thing that a well-funded institution can do for artists is to be well staffed with the right people so that artists can just be artists. One way to think about someone’s personal impact in craft and art is to be loyal to the artists that you love. Respect their pricing and time and stick with the creators whose work you enjoy to support them throughout their career. A jewelry order or a curator wanting to show my work is exciting, but what’s even more exciting is someone who shows consistent interest in my work and makes multiple purchases over time. Knowing someone liked a piece enough to come back is so much more of an encouragement to continue making than any one single order.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

Recently, I’ve become focused on documenting that unreachable craft history in Nicaragua that I mentioned earlier. It was frustrating to meet the end of the resources available to me at the time in the beginning of my practice. Now some time has passed and my research skills and understanding of the political and cultural nuance of Nicaraguan/USA relations has become more apprehensive. I’m ready to pick up the research again in the hopes of finding more and am looking to actual Nicaraguan artists and historians for the information. I’m queer and a craftsperson; both of these communities all over the world rely on oral histories and younger generations’ determination to keep stories and traditions alive. I’m hoping to, in some way, throw my hat into the ring of people willing to do that for Nicaraguan art through this research and eventually through whatever artwork comes out of it.

Contact Info:

- Website: [email protected]

- Instagram: @craftedconfections

Image Credits

-Micah Dillman -Public Works Gallery