We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Sonya Blesofsky a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Sonya, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. Can you open up about a risk you’ve taken – what it was like taking that risk, why you took the risk and how it turned out?

My art practice is unusual in that it’s very improvisational. I make site-responsive installations, and each installation gets made on-site, in-the-moment, based on what I find in the process of excavating or researching a space. Every installation I’ve made has been structured around the possibility for failure, and involves some sort of risk-taking.

To make my site-responsive works, I often cut into gallery walls or create large-scale experimental structures, and so there is always this element of unknown and risk. What will reveal itself when I cut open the wall? Will the system I’ve devised for making this structure actually work? These questions remain unanswered until I get to the physical act of making in a space. I’m never entirely sure what I’m going to find behind a wall, or if the structure/system I’ve devised will actually function when on-site.

In recent projects, I’ve created apertures in gallery walls, to reveal the hidden history found there. Once these openings are cut, I base every subsequent composition decision on what I’ve found. Construction is not as neat and tidy as we imagine—there is often ab-libbing on the part of the contractor or construction worker. Their work gets hidden behind the walls they’ve made, and I respond to the traces of their choices. I consider my work a collaboration with the people who have worked in the space before me.

Sonya, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

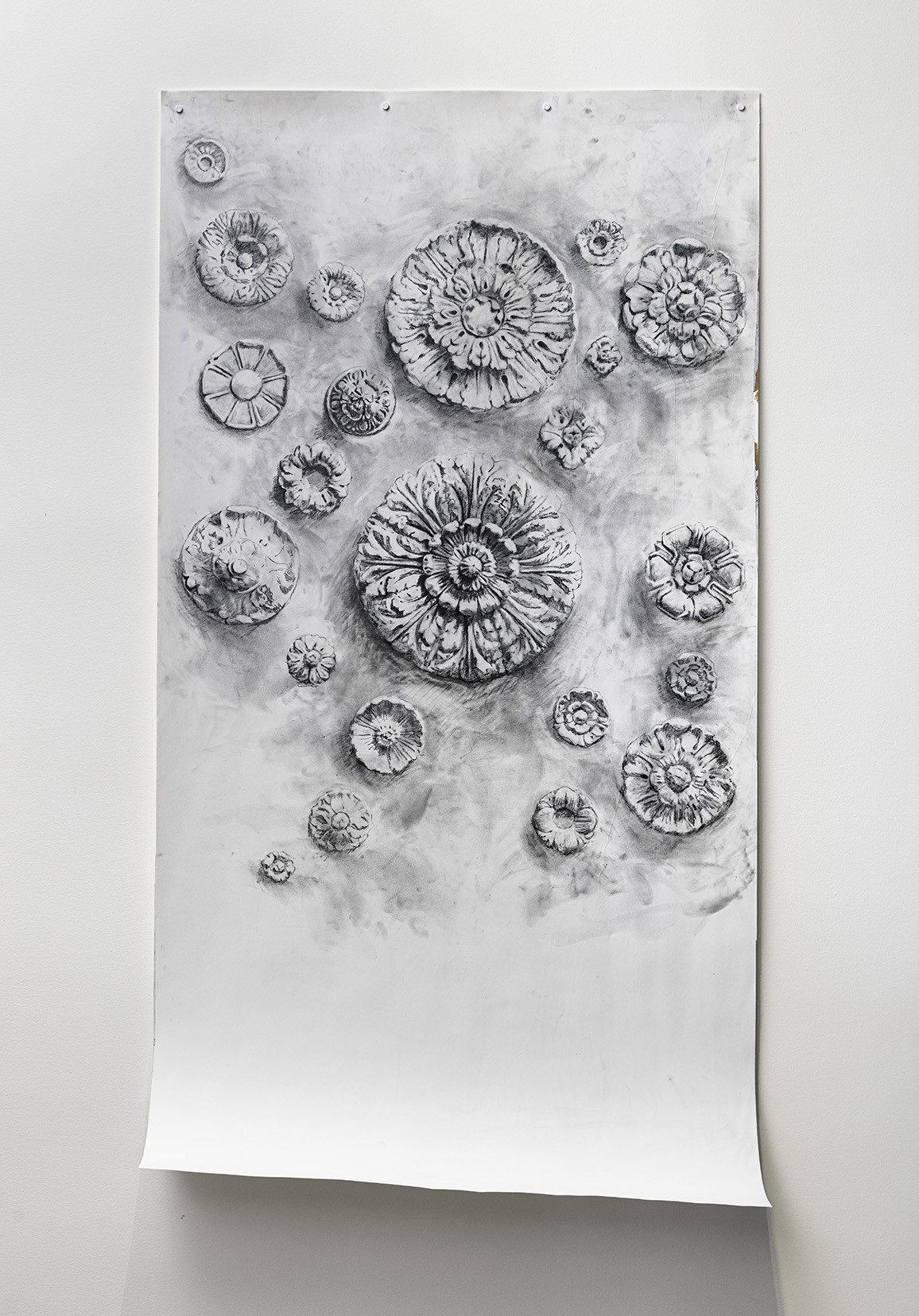

I am an installation artist and educator. My work straddles the line between art and architecture, sculpture and drawing, installation and object, and traditional and unorthodox methods and materials. My work with students comes directly from these different parts of my own studio inquiry, and I strive to bring elements from my artmaking practice into all of the teaching I do. My art practice stretches from making small drawings of historic ornament, to physically-demanding large-scale sculptural installations.

My artwork addresses the changing nature of the built environment and the mutability of history. In my drawings and installations I use history and the changing city as metaphors for memory, transition and loss. I am concerned with the demolition of historic structures and sites, and the disregard for history and cultural heritage that presents itself in the face of redevelopment. What gets lost, and what is gained in the process of development?

Currently, I’m using a virtually obsolete method of making in-situ decorative plaster mouldings to make installations and sculptures. This plasterworking technique is used primarily for restoration, and I am interested in using the language of memory and repair to make this work.

Using an historic process allows me to embody the process of remembering, and in so doing, make it relevant to the stories we need to tell today. From the heritage scholar Laurajane Smith, “Memory, unlike history, has an intimate relation to the present through the personal and collective actions of remembering.” My artwork is a critical act of remembering in the present.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

Everything I do is fueled by my curiosity, my love for learning, and my desire for creating connection. Every step of my artistic process is taken in the name of learning. I consider myself a lifelong learner, and my goal as an artist and educator is to pass along curiosity and excitement for artistic discovery in others. Connection is something I always strive for: I seek connection with people I’ve never met, who see themselves, or their story in my work. With peers and art world collaborators I aim to be fully present in the work we do together to create meaningful relationships. And with students, I share with them my excitement for creative problem solving and model for them the importance of engaging deeply with others.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

For me the most rewarding part of being an artist is that I get to do things in my studio that fall outside of the capitalist means of production. If I want to do something the slowest way possible or follow an avenue I know will lead to a dead-end, I can. I can be inefficient or slow or precious or inclusive or frivolous in my work, instead of having to be efficient and competitive and “productive.” As someone who is interested in imperfection and failure, this gives me great freedom. It’s honestly something that’s so hard to remember, that I often find myself forgetting that I don’t have to follow the rules of “being productive” or doing something the “right” way. I will sometimes spend an entire day in the studio with “nothing to show for it.” And my first instinct is to be a little bit hard on myself about why I didn’t come out with something usable or sellable, or even good. And then at some point on the train or bikeride home I will remember that any work in the studio is worthwhile in and of itself, and all work in the studio is working towards something which will eventually be something important to my practice.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.sonyablesofsky.com

- Instagram: instagram.com/sonyablesofsky

Image Credits

Etienne Frossard