We recently connected with Shivani Malik and have shared our conversation below.

Shivani, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. Can you talk to us about growing your team – how did you recruit the first few people, what was the process like, how’d you go about training and if you were to start over today would you have done anything differently?

I was hired as the first lab scientist for the company. In a quiet yet confident and unhurried tone, my boss—who became more of a mentor over the year—told me my first task was not to do an experiment but figure out how to order lab supplies. We had never ordered a reagent for in-house experimentation. We outsource everything, you see. I saw but did not comprehend the big deal. Of course, I could figure out how to procure reagents. I had a PhD in Biochemistry, six years of cancer biology postdoctoral experience, and a years worth of experience in a mid-sized pharma industry. I had never imagined that the first thing I would learn was what was a W-9 and a W-8 and what it takes to work with finance to get the starting material for an experiment I was supposed to do with my hand in the lab, then interpret it and present it. In short, I was to become a one person lab show.

The solo show went on for a year before an intern joined me. I finally felt like I had a partner, one who I had to teach how to pipette and explain how a lab worked, but one who had the tenancy that belied her youth and inexperience. She became my first hire the week after she finished her undergrad. We made a great team–she, a shy and quiet girl thrilled to be on her first adult adventure, and me, a woman approaching 40 and figuring out how to apply almost 2 decades of scientific training for a meaningful purpose. We did experiments and came up with a plan to further our research plans. My manager supported and understood her. We had the blessing of Maa Saraswati (Hindu Goddess of knowledge and enlightenment), but we needed Maa Lakshmi (Goddess of money and prosperity) to smile at us.

A couple of years into getting the lab operations going on a small scale, the company decided to expand the research footprint and granted me a significant budget to set a state-of-art biology lab and build a team of scientists. I was excited, but had no experience of doing things at that scale. The, now, full time intern and I scouted a new lab space with a contractor and I interviewed several PhD level scientists. My hope was to compel them to join a research group with a novice manager and a program with no published in-house research to show for itself. This was around the time that Covid was disrupting everything around us. The biotech market was insane, and good candidates would not show up for interviews because they already had one or two offers. I had near-misses for candidates that I hoped would join. I hired one senior scientist who, contrary to what I had expected, made my life harder than easier (she taught me very important lesson… my gut could be wrong in judging people); however, my instincts were proven right in terms of three very talented, hard working individuals, who made my team strong.

The next year, I hired another senior scientist who performed better than I had hoped for, and the following year, I hired two more. For most, this was their first industry position, and I was a first-time manager. Together, we learned to grow, made mistakes, learned to admit them, learned from them, and kept pushing forward. Now, we are a solid unit. We look back at our starting days with nostalgia and awe. None of us can believe our good fortune of being part of such a special team.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I am a trained scientist specializing in cancer biology. Over the years, my career in biotech has taken me from being a hands-on lab scientist to leading a team.

Along the way, I have learned that science and leadership are two very different skill sets—each requiring intentional growth, patience, and continual self-reflection. My team, today, is composed largely of women from diverse cultures and life experiences. Working with them has given me an unexpected and profound perspective: our past shapes us deeply and, no matter how different we may look or where we come from, we all share the universal human struggles of belonging, identity, and meaning.

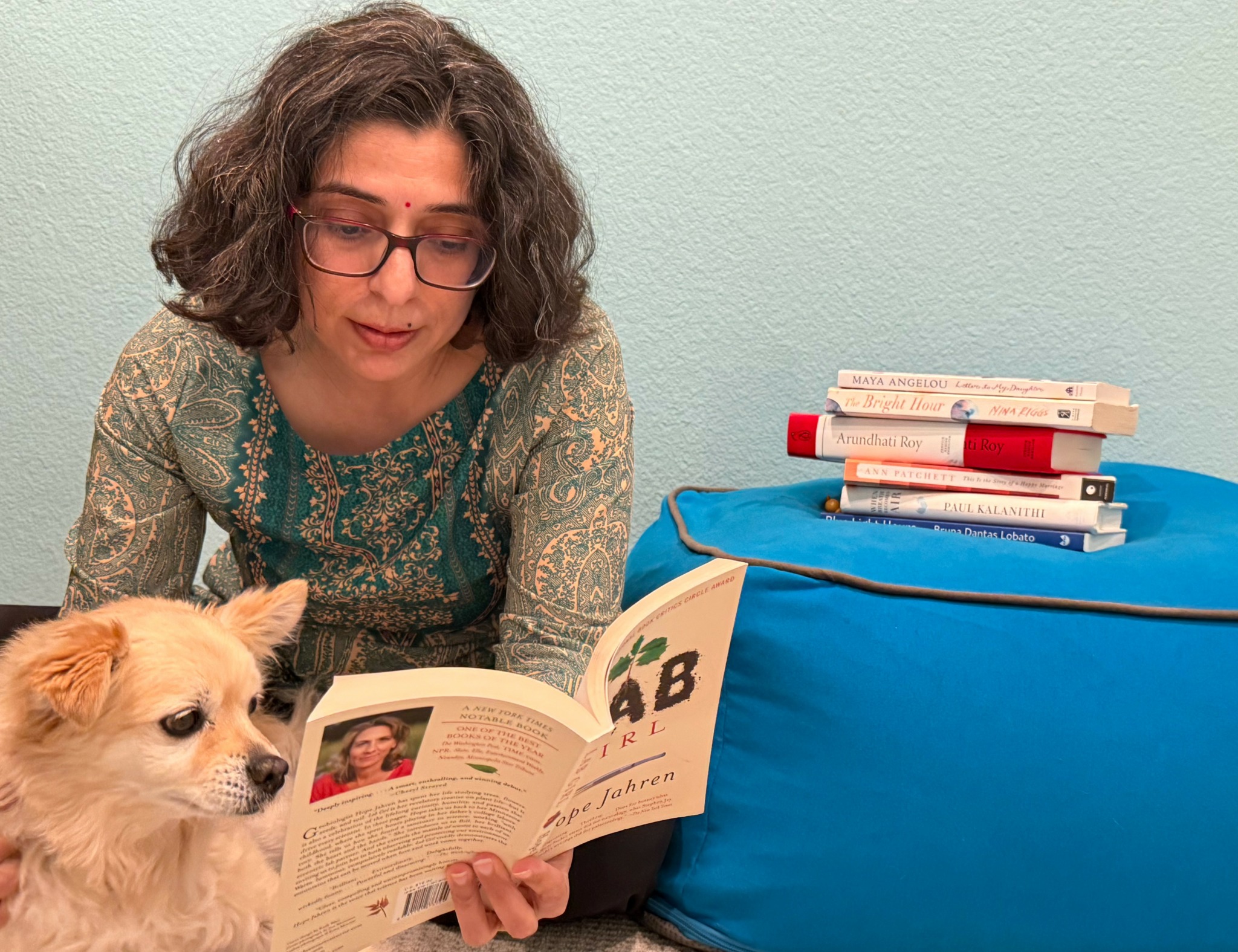

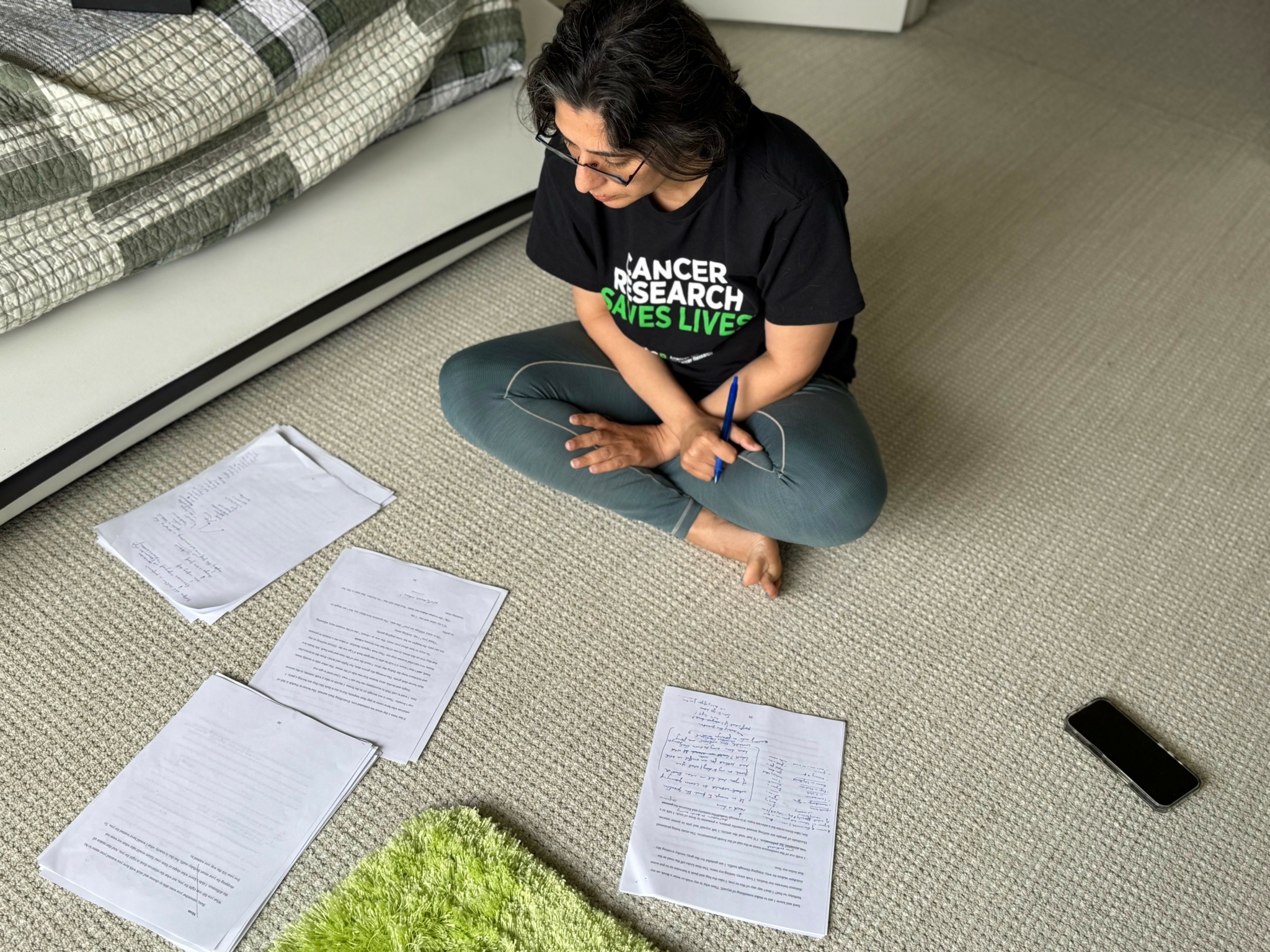

My first book, The Sky Is Different Here, leans heavily into this foundation. Although it is a novel, The Sky Is Different Here is rooted in my experience as an immigrant from India pursuing a PhD in the United States. When I lost my mother during graduate school, I experienced a profound loss of self and a disorienting loss of home. I continued on my scientific path, but internally I faced a crisis about what it meant to live a full and meaningful life. Writing became the space where I could finally reflect, grieve, and rediscover myself.

That process opened me up to truly seeing other people’s stories—their hardships, resilience, triumphs, and the winding journeys that make each of us unique yet connected through a shared human experience. Over time, I began to realize that my work in science, leadership, and writing was not separate at all; they were quietly shaping and informing one another. Each discipline required curiosity, empathy, and the courage to confront the unknown.

In bringing these parts of my life together, something finally started to make sense. I now see my path as one centered on reflection, curiosity, and engagement—with science, with stories, and with people. That convergence is what I’m most proud to share with readers, colleagues, and anyone who is navigating the multifaceted journey of becoming who they are.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

When I began my postdoctoral work at UCSF, I joined a lab that relied heavily on mouse models of cancer. I had never worked with live animals before. I was scared, nervous, and—if I’m honest—more terrified than the rodents themselves, who squeaked and darted around the cages endlessly. My hands shook every time I picked one up. I couldn’t hold them still for the few seconds required to inject the investigational drugs. Each morning, I walked up to the mouse room determined to conquer my fear, and each time I walked out in tears.

A lab colleague and friend saw my struggle and quietly offered to perform the experiments for me until I felt ready. His understanding gave me the courage to keep climbing those stairs to the vivarium, even when my shirt was damp from anxiety. For months, I persisted. I slowly became familiar with the discomfort of being there, but I still couldn’t master the techniques I needed. I began to wonder, what kind of scientist was I, if I was afraid of a mouse? The embarrassment and shame were heavy.

Across the hall, a graduate student was known for her impeccable mouse-handling skills. Her poise and confidence highlighted my awkwardness, but she had a generosity about her that was impossible to miss. One day, I gathered my courage and approached her. I confessed everything; she listened and promised to teach me.

On the first day of training, she placed a mouse on my hand and I screamed. “Did it bite you?” she asked. “No,” I admitted. “Then you’re fine,” she said. And she made me do it again. For a week straight, she repeated this exercise—firm, patient, and encouraging. She praised me for every small step forward. Over the next few months, this “mouse whisperer,” as I came to think of her, worked a quiet magic on me. Her calm confidence became something I absorbed simply by being in her presence.

Eventually, the fear dissolved. I not only learned to work comfortably with mice; I went on to use mouse models for several years—confidently, skillfully, and even joyfully. The transformation came full circle when I found myself teaching the same techniques to new scientists, remembering exactly how it felt to be on the other side.

Any advice for managing a team?

The key to managing a team and maintaining high morale is truly understanding the people you’re leading. Learn what matters to them—what they find meaningful about their work, what motivates them, and where they struggle. As a leader, having clarity on these questions is essential.

When you understand your team on that level, you gain the ability to create an environment where people feel seen, supported, and valued. You can intentionally nurture the aspects of the work that excite them, and you can anticipate when and how to support them during challenges.

High morale doesn’t come from grand gestures; it comes from consistently paying attention, listening deeply, and responding with empathy and intention. When people know their leader understands them, they bring their best selves to the work.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.shivaniwrites.com

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/shivamalik

- Other: https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Sky-is-Different-Here/Shivani-Malik-PhD/9798896360742

https://substack.com/@shivanimalik

Image Credits

Nilotpal Roy

Scott Rifkin

Nicholas Deason