We recently connected with Shih-Hsueh Wang and have shared our conversation below.

Shih-Hsueh, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. Alright – so having the idea is one thing, but going from idea to execution is where countless people drop the ball. Can you talk to us about your journey from idea to execution?

In museums, ideas usually begin with a client’s mission. A history museum may want to honor a community, a science center may aim to spark curiosity, or a nonprofit organization may seek to prepare young people for the future. Our job is to take that mission and translate what can often be dense, heavy content into experiences that people actually want to engage with. That means picturing what visitors will do, see, and feel in every corner of the museum — where they pause, where they laugh, where they reflect.

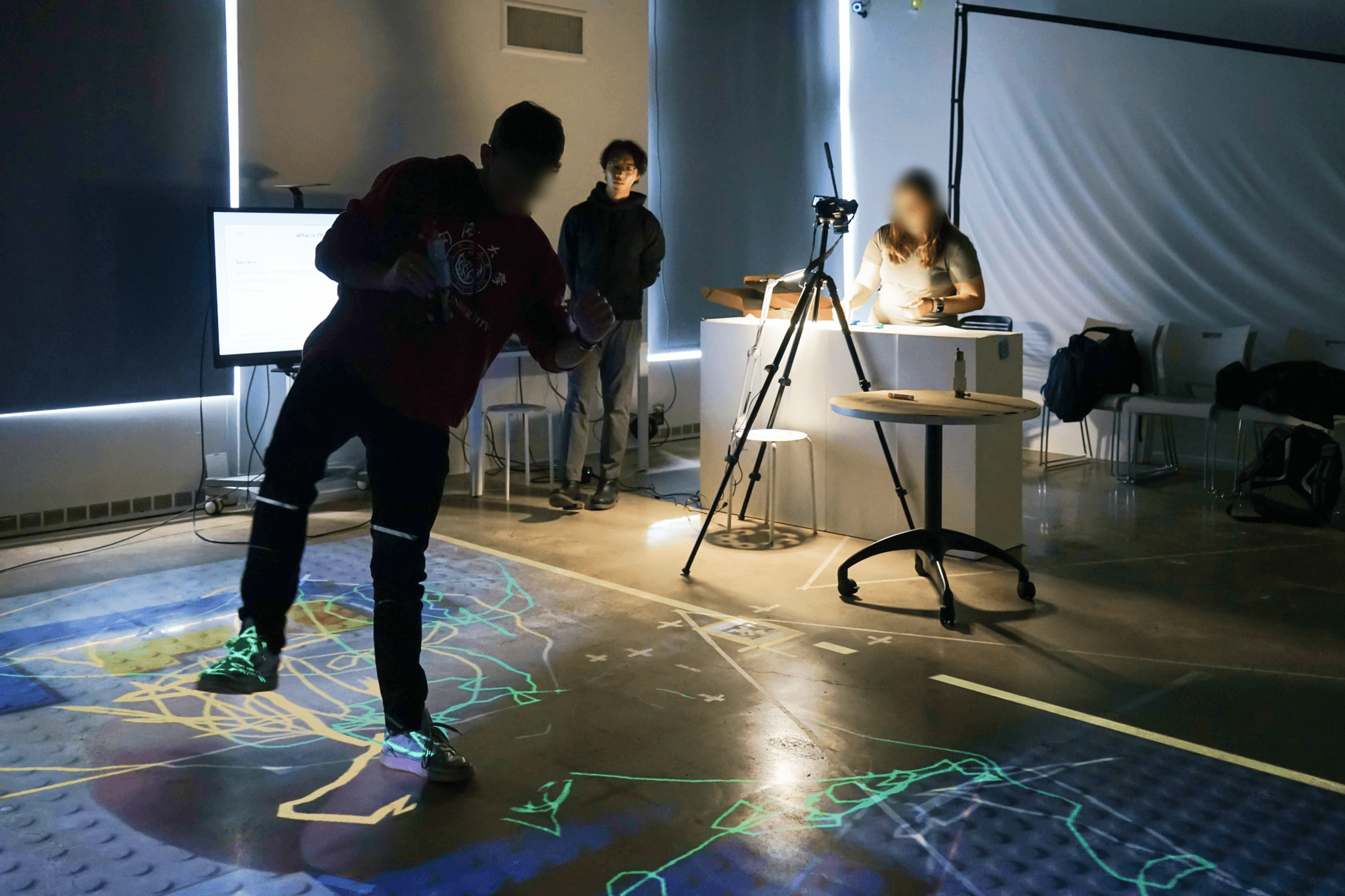

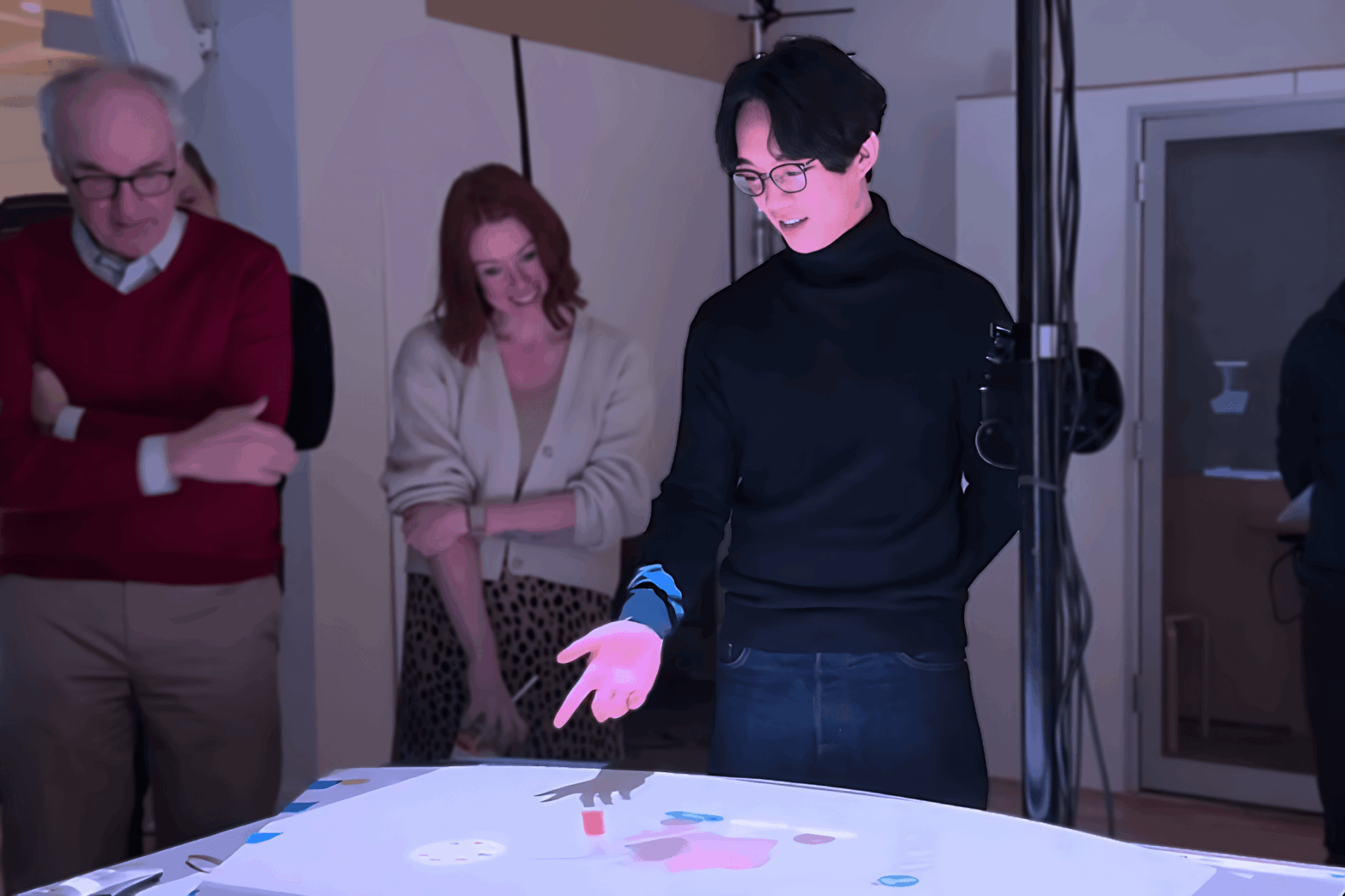

From there, ideas take form in sketches, storyboards, and prototypes. Some are just sticky notes pinned to a wall, others are interactive mock-ups. But no matter the form, they’re only starting points. At G&A Strategy and Design, every idea goes through testing. Concept validation checks whether it makes sense to a visitor in terms of understanding and engagement. Usability tests measure how easy it is to interact and read, and prototype reviews help us spot where breakdowns might occur. Each round reveals new insights, and the design evolves in the process.

However, unexpected problems emerge once an exhibit is physically installed. At the Navy SEAL Museum, a series of touchscreens performed phantom touches. The screen received input even when no one was pressing it. To solve this, we worked with the hardware fabricator to identify the source and proposed design adjustments, such as removing unnecessary touch zones, so the interactive could adapt to the conditions. The goal was not just to fix a glitch but to ensure the design intent stayed intact while making the experience reliable for visitors.

The truth is, execution is never a straight line. It’s iterative, collaborative, and often messy. But that’s where design becomes real. Testing, revising, and on-site adjustments aren’t detours — they’re the process that turns a mission into something people can actually experience.

Shih-Hsueh, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I started in architecture, but what always fascinated me was what happens once people walk into a space. How do they move? What do they stop to notice? What do they ignore? That curiosity eventually pulled me toward user experience design. Over time, I realized that architecture and UX could work together to shape not only environments, but also the stories and interactions that unfold within them.

Early in my career at Steven Holl Architects, I worked on large cultural projects in Shanghai and Beijing. There, I learned how architecture functions as a living system, where circulation, lighting, finishes, and structure must all be coordinated. For example, extending tread depths in the Cofco Cultural & Health Center library turned a stair into both a circulation route and a casual reading space. At the CIFI Headquarters, the curve of a wall and the placement of a skylight were designed to naturally guide people through the building. These experiences taught me how subtle spatial decisions can influence people’s behavior, a lesson I apply in my UX practice today.

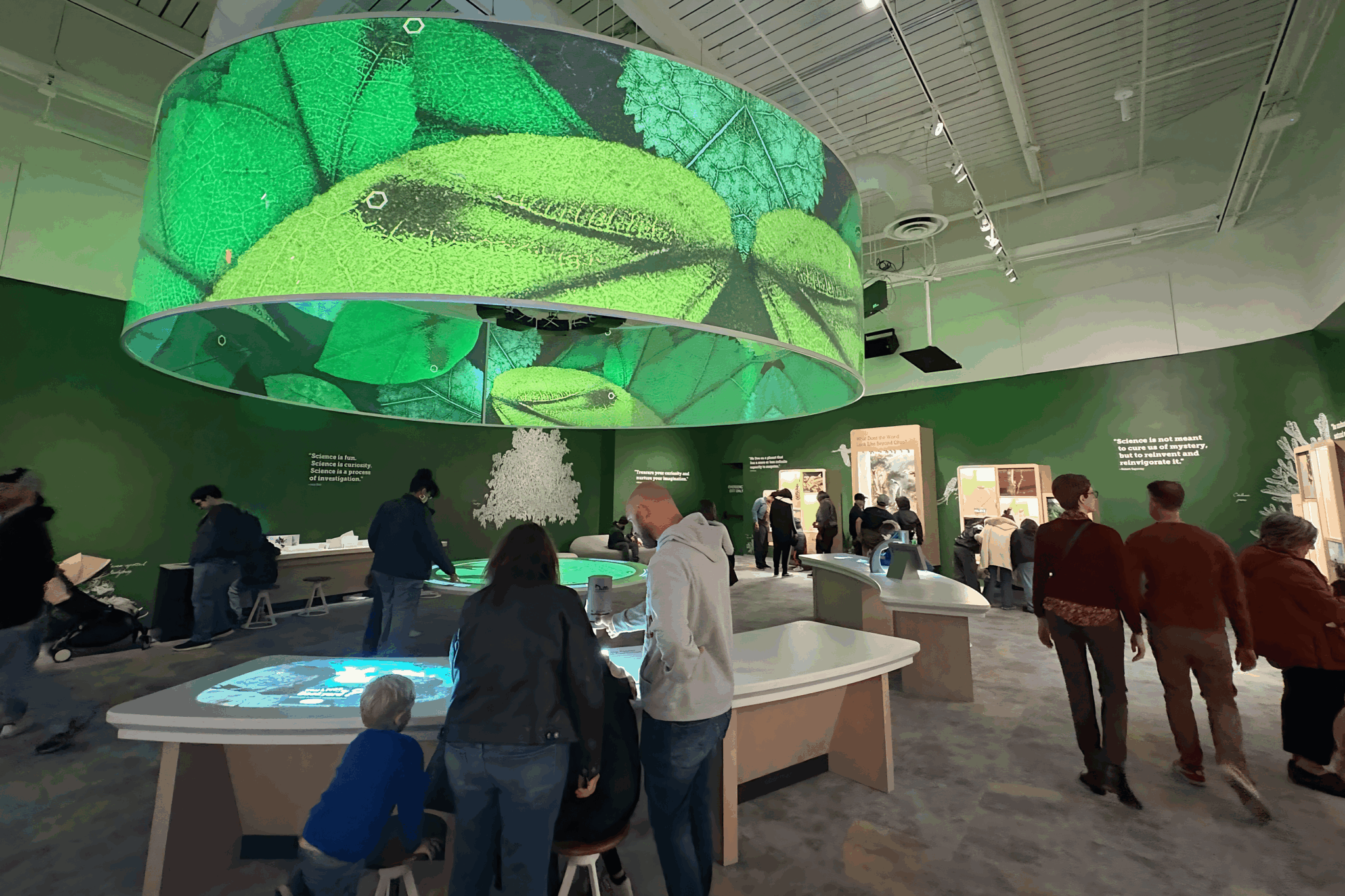

At G&A, I focus on creating interactive installations and experiences, both digital and physical, for museums and cultural institutions, bringing stories to life. I’ve contributed to projects such as the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, the Junior Achievement Dream Accelerator in Colorado, and the Navy SEAL Museum in San Diego etc. My work often centers on visitor touchpoints, for instance, a donation kiosk at the St. Nicholas Shrine, a crank-driven interactive at Cleveland, or the SEAL Memorial Wall in San Diego. Each one is designed to spark curiosity, invite reflection, or deliver clarity in a matter of minutes.

What sets me apart is the ability to bridge worlds. I think like an architect in terms of space, like a UX designer in terms of flow, and like a visitor in terms of instinct. That helps me connect curators, technologists, and educators into one coherent design. Colleagues often see me as the “translator” who ensures ideas from different disciplines don’t get lost, but instead come together as a single experience.

The moments I’m most proud of are when visitors forget they’re looking at a designed object and simply engage with it. A child laughing at evolving cartoon creatures at the Evolution Mechanism in Cleveland, a teenager proudly pinning their strengths at Junior Achievement, or a family standing quietly in front of the SEAL Memorial Wall — those are the moments that remind me why I design.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

For me, it’s the surprises. Before user testing, I usually sketch out what I expect visitors will do, think, or feel. And then — they prove me wrong. They approach something in a way I hadn’t predicted, or they share an interpretation I never considered. Those moments break me out of my own assumptions and make the work stronger. It’s also fun to watch: people who’ve never thought about design suddenly realize they’re part of the process.

The Cleveland Museum of Natural History stands out for another reason. It was the first museum project I worked on from my early internship days through to my role as a full-time UX designer. By the time it opened, it felt like the beginning of my career in the museum world. Watching visitors interact with pieces I had helped shape — seeing them crank, tap, laugh, and learn — gave me a sense of pride and momentum that I still carry with me.

Do you think there is something that non-creatives might struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can shed some light?

UX is often invisible. Even within design teams, people sometimes ask, “What does UX do in this phase?” because it doesn’t leave behind a single artifact, such as an animation, a graphic, or a piece of code. But UX is what ties all those parts together. Without it, the risk is that each discipline focuses solely on its own output, resulting in a fractured experience for the visitor. My role is to maintain a comprehensive view, ensuring that the final outcome remains aligned with the original goals.

Another thing that often goes unseen is just how iterative the process is. At G&A, we conduct concept validation tests, usability tests, and on-site QA. However, even then, things change once the installation is in the gallery. That’s why UX designers go back on-site — not to “fix bugs” but to adjust details so they still serve the visitor experience. Sometimes it’s as small as shifting a label, sometimes it’s rethinking an interaction in response to the unexpected glitches. From the outside, the process might look linear. In reality, it’s a lot of back-and-forth, full of negotiation and adjustment. But it’s in that messiness where real collaboration happens, and that’s often where the design finally clicks.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.shihhsuehwang.com/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/shihhsuw/