We were lucky to catch up with Scott Sundby recently and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Scott thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. One of our favorite things to hear about is stories around the nicest thing someone has done for someone else – what’s the nicest thing someone has ever done for you?

The phone rang at 4 a.m. – never a good sign – and my brother told me that my father’s illness had taken a sharp turn for the worse and he would probably pass within a day. Living in a small town across the country, I was fortunate to book a flight that would get me in that afternoon. I raced to the airport, checked in, and was at the gate when they announced the flight had been canceled. They set up two lines at the gate to rebook us (this is a small airport), and when my turn came the agent informed me that because of my plebian ticket status (I was not a high flyer), they could not get me on the only other flight leaving that day. I explained my father was in his final hours, but, without meeting my eyes, the agent coldly told me there was nothing she could do.

I can only imagine the dazed look on my face as I walked away, when the airline employee handling the other line subtly gestured me over. He had overheard our conversation and quietly told me to get in his line and he’d get me on the next flight. And he did. I made it to the nursing home just in time to tuck my father into bed, sit down next to him, tell him how much I loved him, and thank him for being an incredible father. I kissed him on the top of the head as the attendant ushered me out. The call came in the middle of the night that he was gone.

I stayed with my mom for several months to help her, but immediately upon returning home I went to the airport to find the employee and tell him how he had given me the most precious gift I can imagine. Turns out he was primarily a baggage handler who helped out at the gate in busy times and had since moved elsewhere. For privacy reasons, the airline would not give me his contact information and my efforts to find him through other means have never succeeded (in my more New Age moments, I sometimes wonder if he was a guardian angel).

I now think perhaps it was for the best I never got to thank him, because I have felt that I owe an unpaid debt ever since. Especially when someone asks me to do something and my first reaction is, “I don’t have time for that” or “this is a problem of your own making,” I find myself thinking of the baggage handler who went out of his way to give me a chance to say goodbye to my dad (and no doubt broke a few rules to do so). An act of kindness truly can change someone’s life, and I do my best to live by that lesson.

Scott, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

As with most good things, I got to my current position through being open to taking detours that sounded interesting. I have always loved storytelling and hearing stories, which is why I was attracted to the criminal law as a profession. Trials are fascinating exercises in storytelling and no story is more interesting than a trial where the jury must decide whether to impose the death sentence. When I was asked to participate in a project that involved interviewing jurors who had actually had to decide between imposing a life or death sentence, I jumped at it even though I had to set aside other projects. This decision, which some senior colleagues advised against because they believed as a young professor I needed to write more traditional articles and books, was life changing. Hearing the jurors’ stories made me realize how crucial it is to truly try and understand others’ perspectives if we hope to be effective storytellers — so many assumptions I had made as a law professor about how jurors responded to different types of evidence turned out to be completely wrong! And the only way I could have these conversations with the jurors was to be open to listening to their stories in a non-judgmental way.

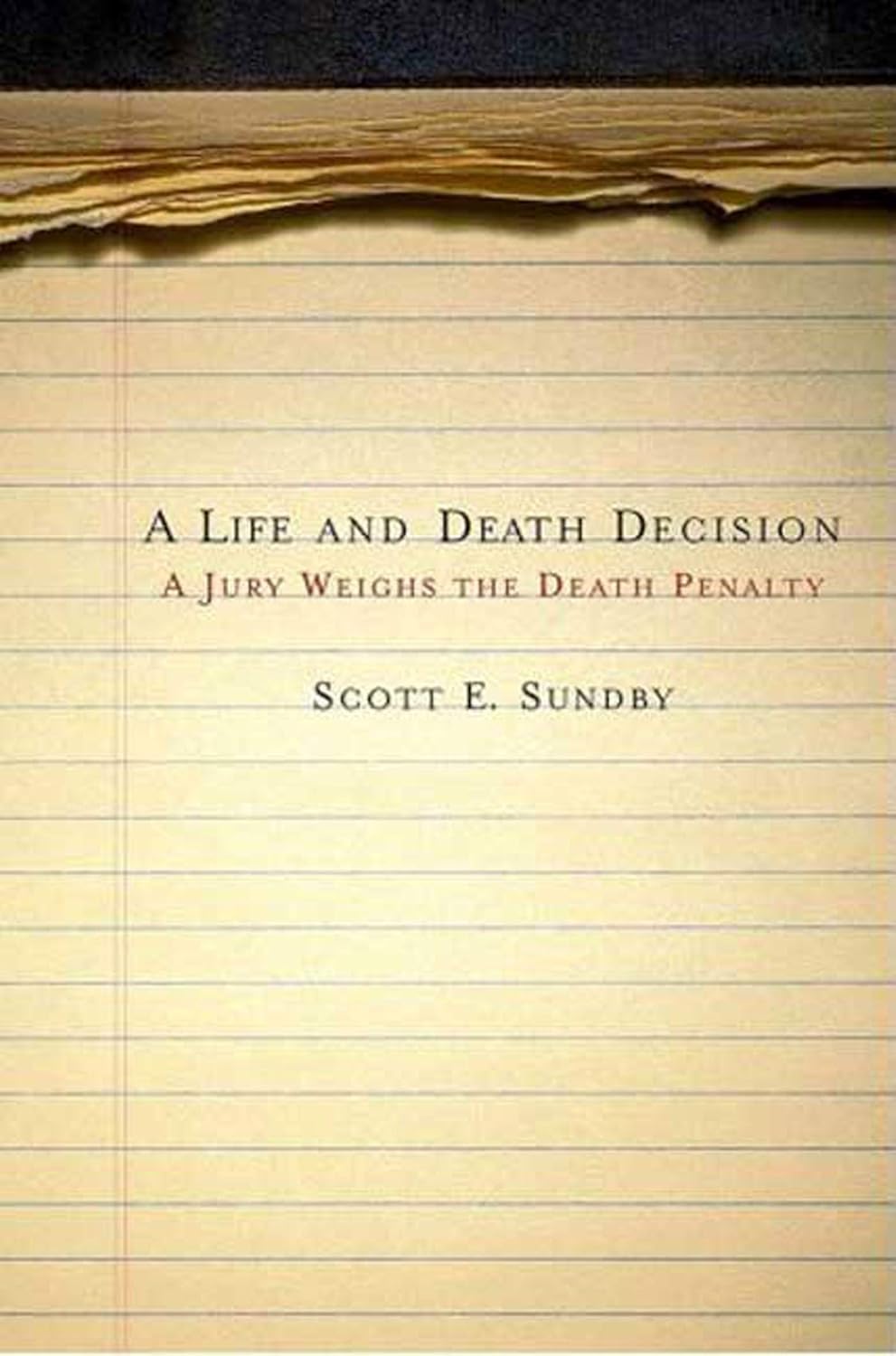

I wrote a book, A Life and Death Decision: A Jury Weighs the Death Penalty, based on what the jurors taught me, and this in turn opened up the next door. I began giving talks to capital defense lawyers on how to best convince jurors to choose a life rather than a death sentence (what we call “the story for life”). Over time lawyers began asking me to advise them on telling the case for life in their specific cases, and I have now consulted on a number of death penalty cases. Through these consultations, I have become convinced of two core premises that shape my worldview.

First, we really are all better than our worst acts. While I have dealt with cases involving truly evil acts, I have yet to deal with a defendant who I found to be truly evil. People end up doing horrendous things for a variety of reasons — such as mental illness, having been horribly abused as a child, addiction (the list goes on and on) — but they also always have redeeming qualities. The crimes are heartbreakingly tragic, but almost invariably so are the defendant’s lives.

The second lesson is that if given a full picture of who the defendant is, almost everyone can be persuaded to choose life over death. Many may scoff at this view as too rose-colored, but I have become convinced that our core instincts as humans is to believe in mercy, redemption and the innate goodness in all of us. The capital defense attorney’s task is to connect with those instincts and bring them to the surface.

Have you ever had to pivot?

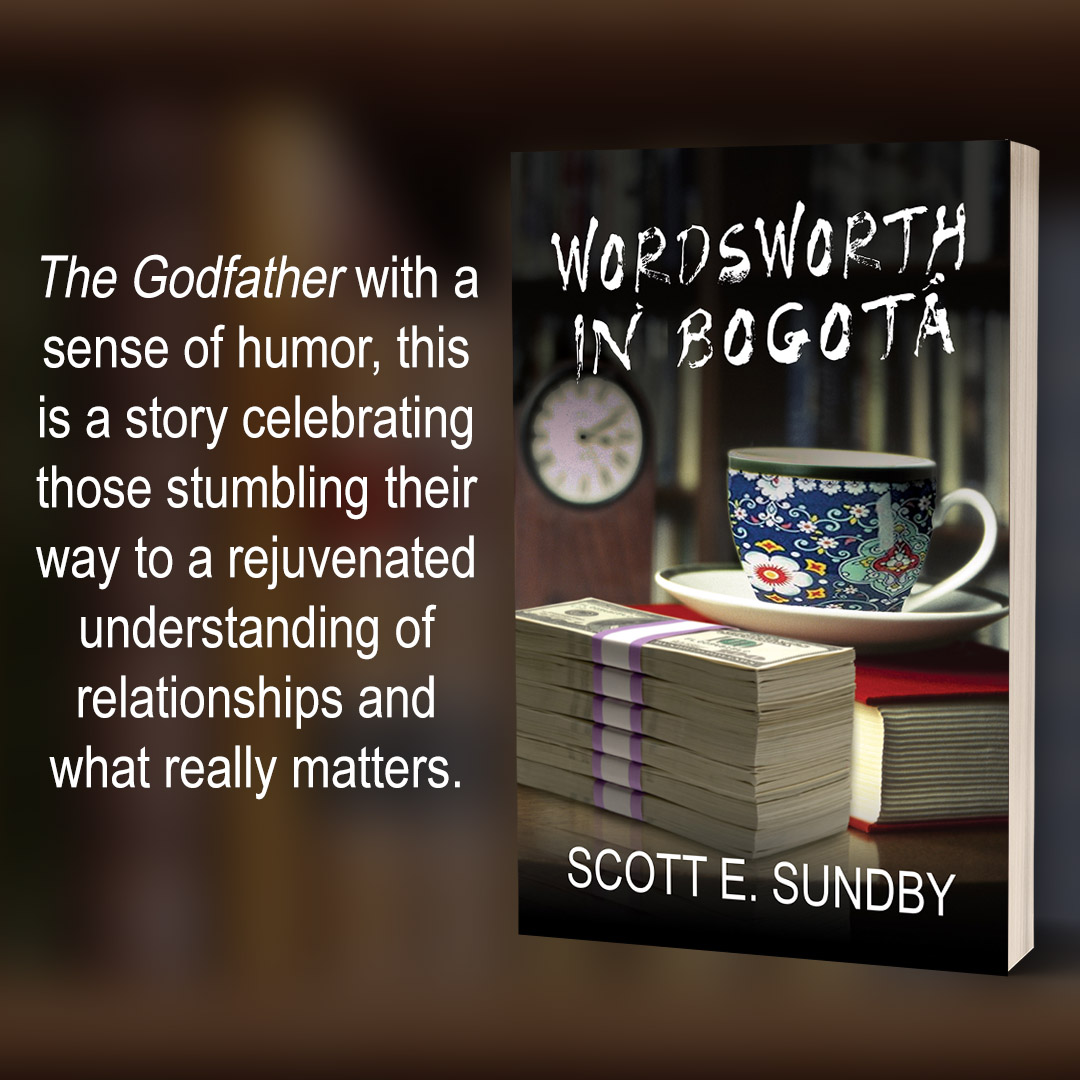

At a number of life junctures, I have found myself becoming too comfortable with what I am doing. Whether it be teaching or consulting, I have reached points where I knew pretty much what I was doing and could do it well. That may sound like a good thing, and on some level it is, but it also meant that I was no longer growing as a person or a professional. As a result, I have tried to embrace any new opportunity even if it scares me to death. Testifying as an expert witness always creates great angst for me, but I do it because others need me to do it and because I am forced out of my comfort zone. Most recently, I published a novel Wordsworth in Bogotá – and felt the anxiety of watching one’s creation thrown out for judgment by the world at large. My favorite quote is by the poet Seamus Heaney, “Walk on air, against your better judgment.” I don’t always have the courage to take that step out onto the “air,” but I try my best to overcome my fears.

We’d love to hear a story of resilience from your journey.

Oh my, as someone who has pretty much always had a four-leaf clover in my pocket when it comes to my legal career, trying to become a published fiction writer was an eye-opening journey, to say the least. I will not go into all the trials and tribulations that faces someone trying to get published in a world where the number of traditional publishers is shrinking and technology has made the number of authors trying to get published skyrocket. I will say, though, that coping with rejection is a crucial part of the journey. I found myself having to become realistic in my expectations of what was likely to happen and also focus on what made the journey satisfying despite the setbacks. And that led to a wonderful discovery — that so much of the creative process is savoring the fun and beauty of creation, and one must focus on that in order to keeping taking steps forward. Thankfully, the novel, Wordsworth in Bogotá, eventually found a small independent publisher, but I became convinced once again that resilience is the greatest attribute one can possess.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.scottsundby.com