We recently connected with Scott Offen and have shared our conversation below.

Scott, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. When did you first know you wanted to pursue a creative/artistic path professionally?

My father was an amateur photographer who treated himself to the best cameras available. Despite that, I had no interest in photography, no matter how much he tried to teach me.

However, in 2012 and 2013, two members of my family required extensive hospital stays, which disrupted the ecosystem of our family. I began looking around me for other markers of human suffering, and I suddenly realized that the area around my office building was full of unhoused people who were suffering even more than I was.

What disturbed me the most was that, even though they were in public spaces, they were invisible to commuters passing through. This group of unhoused people was in plain sight but somehow unseen. In fact, people would walk over them in order to get where they needed to go.

I decided that I could no longer blind myself to their pain any more than I could ignore pain in my own family. So I picked up a camera as an instrument for making their suffering visible. I thought: it’s possible to turn away from a person, but people tend to look at photographs intently.

I began taking photographs—always with the permission of my subjects—and this became a project that lasted seven years. That’s how I started.

Scott, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I am a photographer, and I began to photograph in 2014. At first, I did street photography and photographed groups of strangers with whom I became close over time. At the time, I was looking at many photographers from whom I could get insight.

One day in class, my professor said, “You have created a family of choice—why wouldn’t you photograph your own family?” She suggested two photographers, Emmet Gowin and Harry Callahan, who had been her teachers and were famous for family photography or for photographing their partners.

So I asked my partner Grace if she would be willing to collaborate with me on a project in which she would create various personas that modeled aspects of herself. The work was not biographical or candid. Every image was staged with the purpose of dealing with ideas of collaboration, gender, aging, and the dynamics of authorship through a sustained photographic practice.

These ideas are expressed through the habitation of an older woman in a landscape that is mysterious, fantastical, and sometimes scary. In 2025, this work was published as a book by L’Artiere Edizioni.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

I am drawn to the physicality of analogue photography. When I was first introduced to the darkroom, I often worked twelve to eighteen hours at a stretch. I love everything about it—the quiet, the darkness, the complete absence of distractions. In that space, I can focus like nowhere else. I am fascinated by how film, chemicals, and paper can be combined in countless ways to produce an infinite variety of prints, simply by altering the sequence or balance of ingredients.

While analogue photography may seem simple, it demands deep experience and knowledge to produce the image you envision. In a digital world, I value that film photography engages both the hands and the mind.

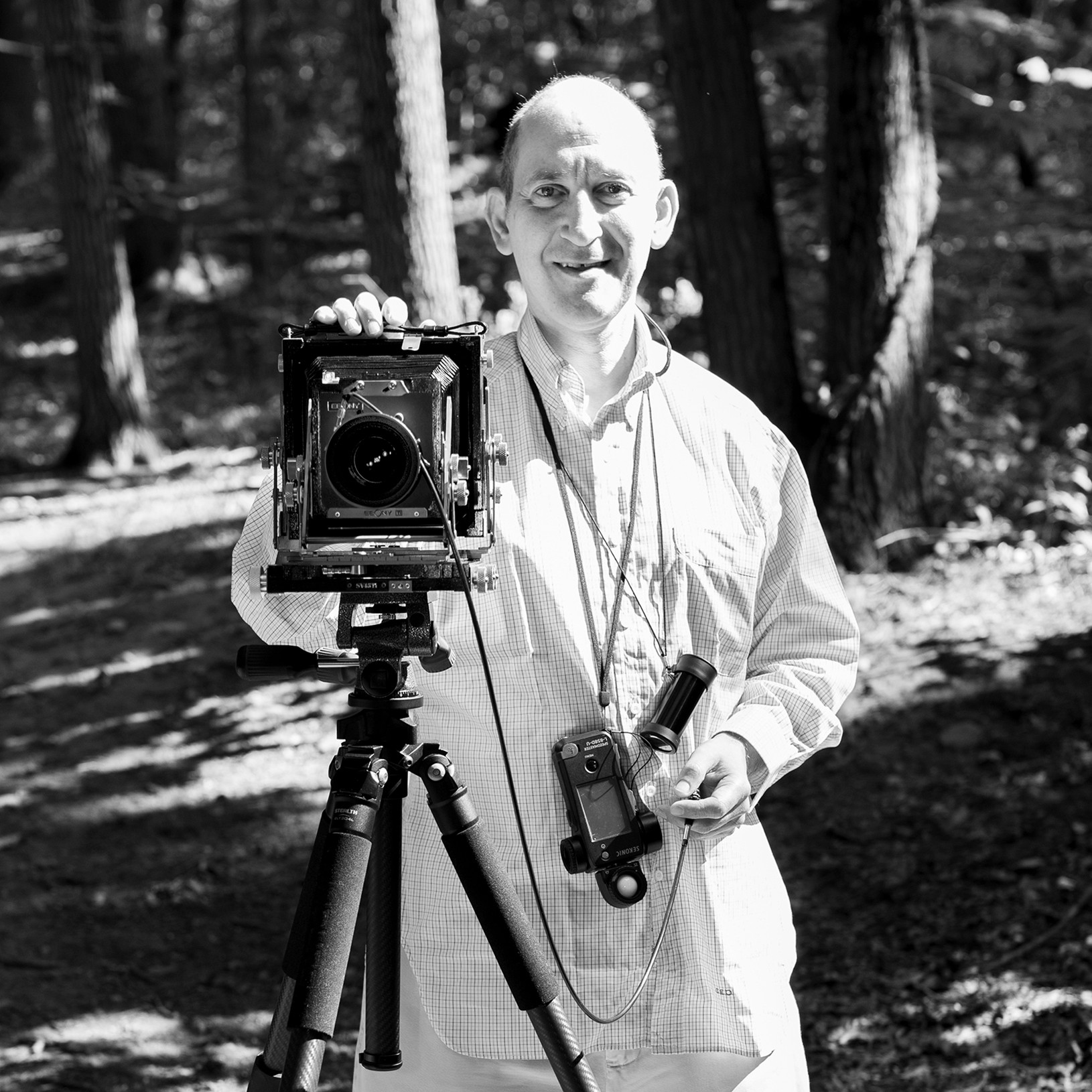

I work with large format cameras, and part of their appeal is the deliberate pace they require. Each photograph is the result of a slow, attentive process. The weight of the camera and equipment demands purpose from the moment I step outside. Nothing is casual or incidental; intention is present from the first decision to the final print. In a fast-paced world, I find joy in doing something slow—something that resists haste and rewards patience.

Are there any books, videos, essays or other resources that have significantly impacted your management and entrepreneurial thinking and philosophy?

The books that informed my practice include those featuring the work of Harry Callahan, Emmet Gowin, Eugène Atget, August Sander, Seiichi Furuya, Raymond Meeks, Andrea Modica, Laura McPhee, and Barbara Bosworth. In terms of technical study, I have relied on the “Ansel Adams Photography Series” — “The Print,” “The Negative,” “The Camera” — as well as Henry Horenstein’s “Black and White Photography: A Basic Manual” and “Beyond Basic Photography,” “The Film Developing Cookbook” by Bill Troop and Steve Anchell, “The Darkroom Cookbook” by Steve Anchell, “The Photographer’s Toning Book” by Tim Rudman, and “The Book of Pyro” by Gordon Hutchings.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.scottoffen.net

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/offen1645/

Image Credits

@ Scott Offen