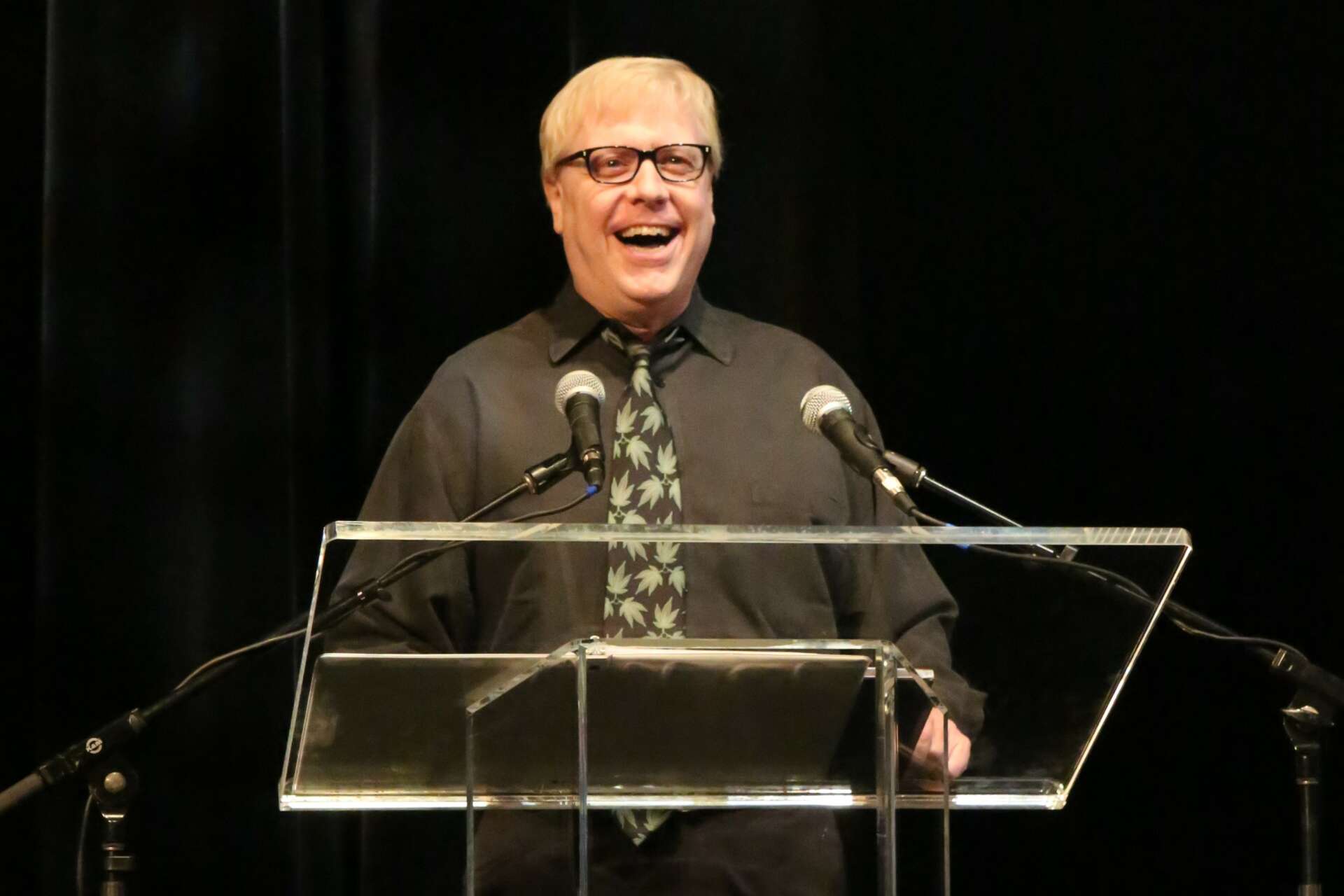

We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Scott Miller a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Scott thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Alright – so having the idea is one thing, but going from idea to execution is where countless people drop the ball. Can you talk to us about your journey from idea to execution?

I’ve been directing and writing musicals since 1981. I’ve written the book, music, and lyrics for ten musicals and two plays, and I’ve also written more than a dozen books about musical theatre. My life has been a pretty direct path to where I am now.

My parents started me on piano lessons when I was four. And even from that early age, they knew they could only keep me interested if one of the pieces the teacher gave me to work on each week was a show tune. I can remember (around age 5 or 6?) pounding out “Tradition” from Fiddler on the Roof for weeks on end. Drove my mother batshit. They tried to get me to take up trumpet as well in fourth grade, and I stayed with it for three years, but I hated it because I couldn’t sing along and it didn’t sound anything at all like the cast albums. At least the piano could approximate the sound (most of the notes at least) of the full orchestra. And I could sing along!

When I was fourteen, I switched to a new piano teacher, St. Louis jazz pianist Carolbeth True, who taught me how to use the skills I’d learned all those years. Suddenly, I was practicing two or three hours a day, just because I loved it. Best piano teacher I ever had.

Then in high school and college I got my dream job — ushering at The Muny, the world’s largest outdoor theatre. From 1980 through 1987, I wore that godawful polyester red coat in the sweltering St. Louis summer heat so that I could watch musicals every night. It was like the perfect college survey course, planned out just for me. I saw shows I would have never otherwise seen, like Carnival, High Button Shoes, Li’l Abner, George M, Hans Christian Andersen, Shenandoah, They’re Playing Our Song, Where’s Charley?, The Apple Tree, Funny Girl, Oliver!, and others. And the usher captains were always so cool about stationing me down close to the stage so I could see everything.

In high school, I got to perform in an outstanding survey of the art form, including a classic Cole Porter musical comedy (Anything Goes, 1934), two Rodgers and Hammerstein classics, their first (Oklahoma!, 1943) and their last (The Sound of Music, 1959), a Lerner and Loewe classic (Camelot, 1960), a rock musical (Grease, 1972), and a brand new show, the first one I ever wrote, called Adam’s Apple. It was also in high school that I saw Grease and The Rocky Horror Picture Show for the first time, both of which blew my musical theatre mind.

Later on, I would also get to perform in Godspell and to play the role I had always wanted, Cornelius Hackl, in Hello, Dolly!, across from my best friend Chris Penick as Barnaby. But that was the end of my acting career. Directing and writing were a lot more interesting to me.

I went to college at Harvard and discovered only after I arrived that there was no theatre department. So I was a music major instead and it was the best accident so far. I learned music theory and history and they have both been very valuable in the years since. And my sophomore and junior year theory professor was the amazing Peter Lieberson, a composer himself, but also son of Goddard Lieberson, onetime producer of the cast albums of Camelot, My Fair Lady, Kiss Me Kate, South Pacific, West Side Story, and other classics. Peter’s mother was Vera Zorina, onetime ballerina and Broadway musical star. Peter really encouraged me as a composer and he taught me an important lesson — that an artist needs to learn the rules and history of his art form, even though he might periodically reject them, or only call upon them in a pinch.

And another teacher at Harvard, Ann Dhu McLucas (then Shapiro), also took me under her wing and together we created an independent study program for me over several years, analyzing in real depth the scores of quite a few Broadway musicals, laying the groundwork for the books and essays I write today.

Because there was no theatre department at Harvard, the theatre scene was an artistic Wild West. You got whatever space you could and mounted a show however you could. Because of this anarchy, there were 30-40 productions opening each semester, everything from Antigone to Dames at Sea. It was heaven. I produced my shows in common rooms, dining halls, a former library, but never in an actual theatre. Some friends and I started the Harvard Off-Key Musical Theatre Company, though we only produced a few shows. I learned there how to do the kind of low-budget, (almost) guerrilla theatre that would later mark the early years of New Line.

While I was in college, my high school drama teacher Judy Rethwisch and I stared a community theatre group back in St. Louis called CenterStage, active only during the summers until I graduated and we could produce full seasons. Again, though it wasn’t intentional at the time, I see now that the shows we were producing were a personal little master class just for me. We did Hello, Dolly!, No, No, Nanette, Carousel, How to Succeed, and other classics, along with some more contemporary shows, like Godspell, Little Shop of Horrors, and Best Little Whorehouse. I had seen these classics at the Muny, but now I could actually work on them and figure out what makes them tick.

And once we were doing full seasons, I started creating these “Tribute” concerts, whole evenings of songs by one writer or team. Sometimes, there’d be historical narration between songs, sometimes just song after song, sometimes with a little staging, often none at all. I created Tributes to Cole Porter, Richard Rodgers, Lerner and Loewe, Stephen Sondheim, and later on, a “Tribute to the Rock Musicals” and a “Tribute to the Dark Side.” In almost every case, one of my priorities was to recreate exactly as possible each song’s original performance, context, staging, etc. I realize now I was working my way through the masters of the art form, learning from them by working on them. Just as music theory students imitate Bach to learn composition rules, I was imitating the masters of my art form for the same reason. Just as I had to take three years of music theory as a foundation, these concerts did the same for me in terms of musical theatre. I continued this series into the early years of New Line.

While I was running CenterStage, I got a job at Dance St. Louis, first as a telemarketer, then as the assistant to the operations manager, and finally as the development director. It was there that an amazing man named Adam Pinsker, DSL’s executive director, taught me the finer points of arts administration. He had worked in the field for decades and once again I had my own independent study. And on top of everything else, he let me stay after hours to work on CenterStage stuff.

In 1991 I was ready for adventure. So I left CenterStage and started New Line Theatre, right at the beginning of the new wave of nonprofit “art” musical theatre that swept the country in the early 1990s. By the time I left Dance St. Louis in 1994, New Line was off and running. Within a few years I also began writing articles about musical theatre and in 1996 my first book was published.

It’s funny now, looking back, to see how freakishly direct the path has been. And it was almost never because I planned it that way. I believe, like Joseph Campbell, that it’s not about charting a course or planning a timetable; it’s about following your bliss. If you do what you love most and you do it your very best, good things will result. That being said, I’m aware how lucky I’ve been all my life to get all the opportunities I’ve gotten. I was repeatedly in the right place at the right time because I was always following my bliss, never straying from the path for a second.

I remember, right after college, Maritz offered me a job writing industrial musicals, i.e., short musicals for trade shows and conventions about how much GM loves its employees or about how cool the new line of Ford trucks is gonna be. I read some of their previous shows to learn the house style and they horrified me. I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t write musicals to increase sales or introduce the new line-up. Musical theatre is sacred to me. It’s not about selling trucks. So I passed on the job. Best decision I ever made. Worst for my finances.

But that choice gave me the space to launch New Line Theatre, “the bad boy of musical theatre,” producing only adult, relevant, challenging musical theatre since 1991.

The musical theatre is one of our few indigenous American art forms, one of America’s greatest artistic gifts to the world, and New Line treats it with the seriousness, respect, humor, and joy that it deserves. Actor Laurence Luckinbill once wrote to me, “Go broke if you must, but always over-estimate the public’s intelligence. They’ll thank you for it.” So that’s the guiding light of New Line Theatre. Luckinbill was right.

Scott, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I founded New Line Theatre, “The Bad Boy of Musical Theatre,” in 1991, at the vanguard of a new wave of nonprofit musical theatre being born across the country, offering an alternative to the commercial musical theatre of New York and Broadway tours. New Line’s mission is to involve the people of the St. Louis region in the creation and exploration of provocative, socially and politically relevant works of musical theatre – daring, muscular, adult theatre about sex, violence, race, politics, the media, obscenity, art, religion, and other issues.

New Line produces rock musicals like Hair, American Idiot, The Rocky Horror Show, Head Over Heels, Passing Strange, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, High Fidelity, and Cry-Baby; concept musicals like Assassins, Love Kills, Lizzie, Chicago, and Cabaret; abstract musicals like A New Brain, Jacques Brel, and Songs for a New World; absurdist musicals like The Cradle Will Rock, Urinetown, and Johnny Appleweed; radical new takes on shows like Jesus Christ Superstar, Evita, Man of La Mancha, Anything Goes, Pippin; lesser known shows like Bat Boy, The Nervous Set, The Wild Party, The Story of My Life, Floyd Collins; and lots of Sondheim musicals.

New Line was honored with a special St. Louis Theater Circle Award in 2014 for the company’s body of work over the years. And in 2019, New Line received the What’s Right With the Region Award from Focus St. Louis, for Fostering Creativity for Social Change. The Riverfront Times calls New Line “St. Louis’ premier company when it comes to raw-nerve theatrics.” Alive Magazine says, “New Line puts on performances that Stages St. Louis and The Muny wouldn’t dream of doing.” The St. Louis Post-Dispatch named New Line the Best Theater Troupe for Musicals, St. Louis Magazine named New Line the Best Theatre in St. Louis, and Alive honored New Line as the Most Provocative Theatre in St. Louis. American Theatre magazine called New Line’s work “almost unbearably emotional.”

In recent years, the company has been honored with entries in the Cambridge Guide to the American Theatre and the annual Theatre World, and New Line has been featured in two other books (one on labor poster art, one on Gaslight Square), and in two documentaries (one about Hair, one about The Nervous Set.) The book The Poster Art of New Line Theatre was published in 2018.

The musical theatre is one of our few indigenous American art forms, one of America’s greatest artistic gifts to the world, and New Line treats it with the seriousness, respect, humor, and joy that it deserves.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

Our company almost went out of business when the pandemic hit. But our supporters really stepped up, and even when we weren’t producing shows for more than a year, the contributions kept coming in. I saw the people valued what we create, even more than I had realized. We emerged from the pandemic cautiously in fall 2021 with a two-actor musical, with me on solo piano. In order to keep the company spread out, we could only seat about 75, but the audiences came! They were so thrilled to be back in the theatre again. I had always known how important storytelling is to us humans, but I hadn’t fully understood till then how much people need storytelling — especially LIVE storytelling. We need that connection.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

The goal of my work with New Line and with the books I write is to share with people the incredible complexity and sophistication and imagination and variety of great musical theatre, this chosen art form of mine. With New Line, we produce shows that most people have never seen, but we learned long ago — it’s wrong to think people only like what they know; people like what’s GOOD.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.amazon.com/stores/Scott-Miller/author/B000AQU1LC

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/newchaz64/

- Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/@scottmiller864

- Other: https://newlinetheatre.blogspot.com/

Image Credits

Production photos are by Jill Ritter Lindberg. Not sure who took the photos of me…