We were lucky to catch up with Sarah Elizabeth Schantz recently and have shared our conversation below.

Sarah Elizabeth, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Can you open up about a risk you’ve taken – what it was like taking that risk, why you took the risk and how it turned out?

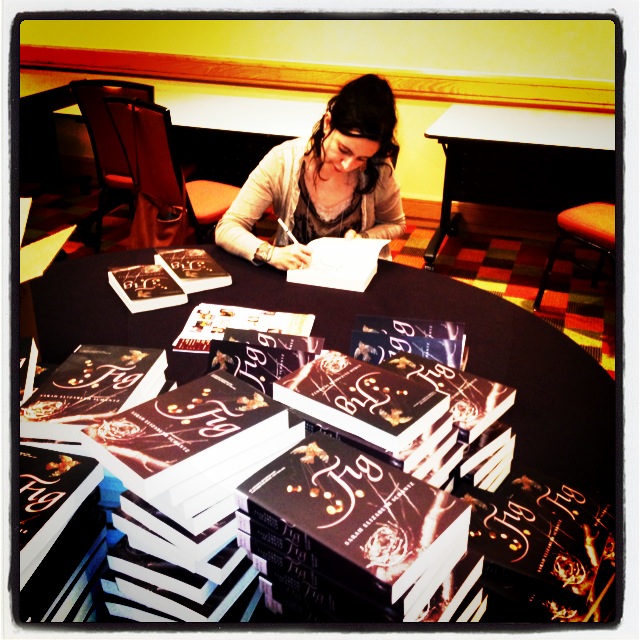

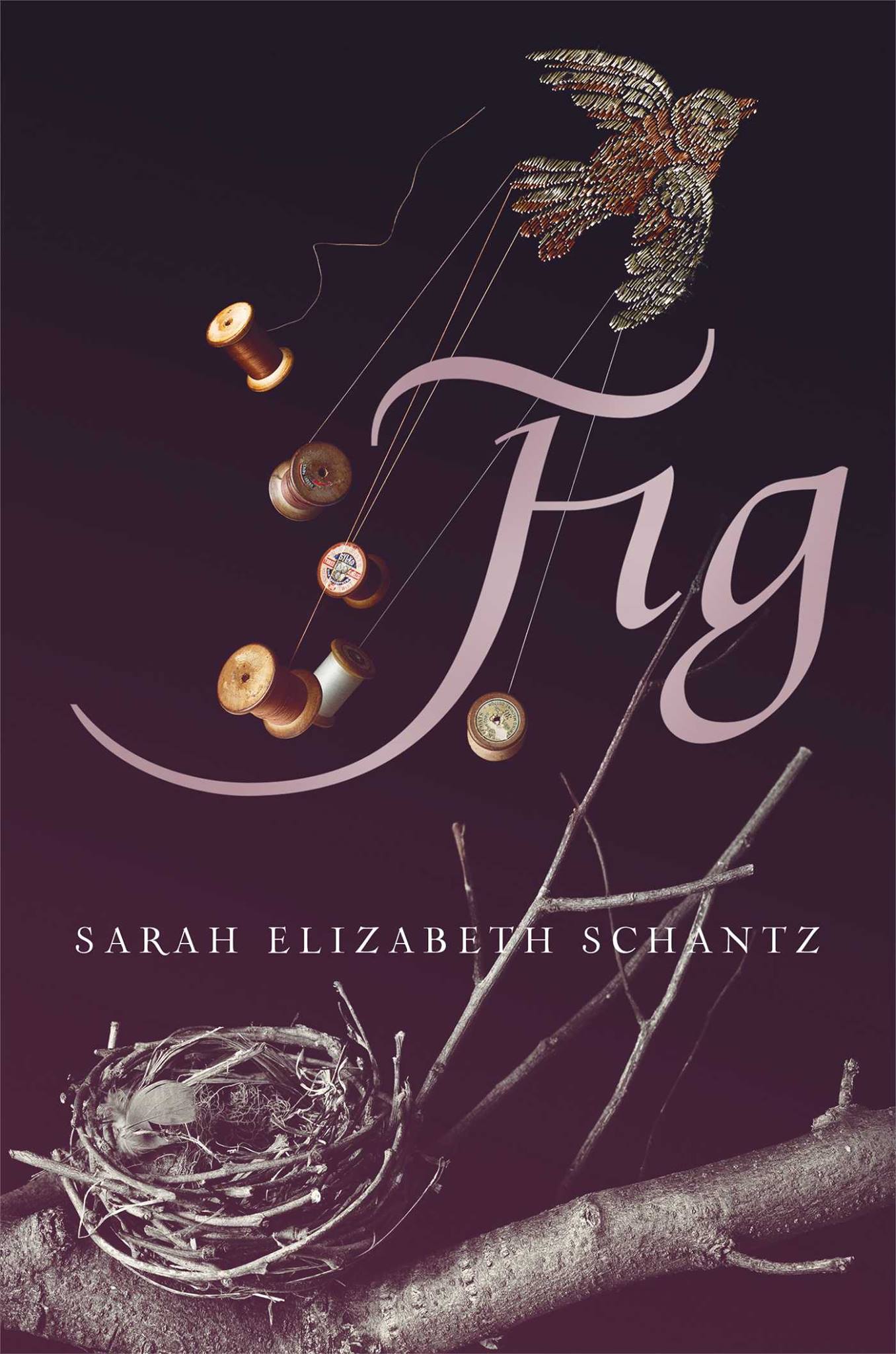

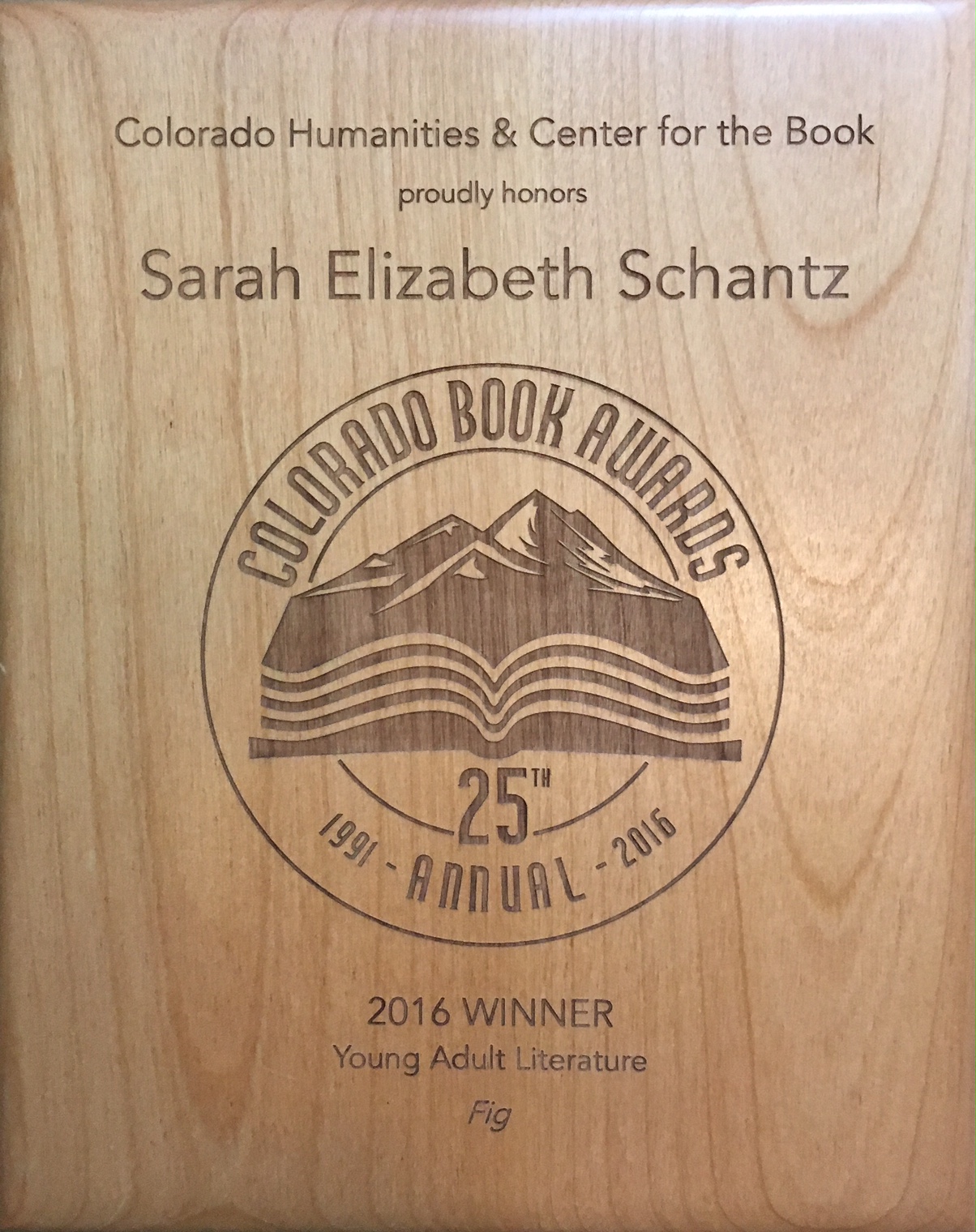

I’m about to take the biggest risk I’ve ever taken. The long story made shorter is that my mother died in 2011 from pancreatic cancer while I was finishing my MFA and desperately trying to complete a first draft of what would be my first novel Fig so she might read it before she passed. While this didn’t happen because I focused on being present with her and caring for her at home, I did finish the book shortly after, was “discovered” by an agent, and sold it to an imprint at Simon & Schuster to then be selected as a Best Read of the Year by NPR and win a 2016 Colorado Book Award. The joy was bittersweet, especially when my oldest daughter Kaya died in 2018 unexpectedly at the age of 26 and shattered my family. In 2023, we were just beginning to find a way to live with her absence as a presence when my father died from glioblastoma twenty-one days from diagnosis (and the first visible symptoms). My parents owned and operated a bookstore in downtown Boulder which my dad was still operating on a smaller level from the mountain home he owned outside of Lyons, Colorado. Again, the long story made shorter is that a nightmare followed his death where it took a year to get the house ready to sell (I am still trying to unload 10,000 rare and used mystery novels). While a reverse mortgage company owned most of my father’s property when he died, my husband and I were able to walk away with a nest egg we hoped to put down toward owning a home of our own for the first time, a major dream of ours for so many reasons including the fact the first time I recall seeing my mom cry was when I was three and we’d been evicted, but also living in poverty forever as an adult with two kids, working all the time but not being able to get ahead because of a disability I have, and because it’s expensive to be poor. Because my dad had turned into a hoarder as a result of his grief, likely compounded by the panic buying and stocking up of the lockdown, my husband in particular was exhausted from all the physical and emotional labor he put in from June of 2023 to June of 2024 to get the house emptied and repaired.

Once the house did sell, and we did call it done, he was looking for work having been forced to leave his job to deal with my dad’s property, and as lovely as it was to have him at home from June of 2024 to December of 2024 cooking and cleaning while I continued to teach, do divination, one-on-one manuscript midwifery, and write, I was still working 60-80 hours a week to pay the bills while we took a much-needed breather before deciding where to move and what we could afford to buy. It was such a blessing to be able to spend that much time together after the year of hell and the strange hours he had before my dad died working as a custodian and I will be forever grateful for this time. On December 17th, 2024, at 2:30 in the morning I awoke to him shaking me to find him kneeling at the edge of the bed clutching his chest, repeating the words, “I need to go somewhere. I need to go somewhere.” He was pronounced dead at 5:05 a.m. that same morning after a pulmonary embolism took the cardiologist by surprise after inserting a stent to open up the “widow maker” valve.

The last six months have been a blur of the most intense grief I have ever experienced mostly because I don’t have him to process it with like I did when our oldest daughter died. Because we’d been together for twenty-six years, his death means not only the death of my everyday routine, a death of who I was, it’s a death of who our other daughter Story was. I can’t stand to see my baby have to lose another person so close to us when she is still so young (only twenty-four). But I just went under contract to purchase my first home which I would not have been able to do without the money we got from my dad’s estate, from the sacrifices my husband made, from a lot of help from friends and community (since I don’t really have any family anymore, just a few precious cousins who are busy as they should be with their own families and lives). I am planning on using one of the bedrooms as a retreat space I rent out to artists looking for a quiet and inspiring place to hunker down and really focus on whatever intensive work their projects require with me nearby to offer mentorship, divinatory direction, and what I call creative midwifery. It’s the kind of retreat I dreamed of being able to go on when my kids were young, and even now. A room of my own as Virginia Woolf would say, only one solely dedicated to a work-in-progress where your life back at home isn’t able to call you away to do the dishes or feed the family or fix the faucet in the bathroom or whatever other nagging To Do’s there might be). While writing retreats such as the one I just taught in India at the Himalayan Writer’s Retreat are delightful, they are one part vacation and tourism, and not always as conducive to actually generating new work right then and there. What I’m offering is the potential for someone to work all day on a manuscript with tiered levels of guidance and support from me. I’ve been wanting to do this forever and I knew the property would either need to be rural to be appealing or to be in a charming area of a charming town close to parks and restaurants the artists could walk to and explore. Rural just wasn’t an option, especially now that I am widowed. But then I found the PERFECT restored Victorian bungalow in Old Town Longmont, and after not getting the first similar house I tried to purchase, I didn’t think it would go my way, especially when I saw there would be a lot of competition, and for good reason.

About a decade ago I read Amanda Palmer’s memoir and encouragement tool, THE ART OF ASKING where she reflects on her journey as an artist who uses crowdfunding, and that book has been instrumental in helping me understand it’s impossible to make it as an artist in today’s world unless you come from a lot of financial privilege and net worth which I did not (my parents were literally bohemian brick-and-mortar to actual “barn” booksellers, and while they did really well because they worked really hard, my dad was still backed into a corner after my mom died and a devastating flood caused him to lose close to a year of work because the bookstore was all mail-order by then and there was no way to send them when the highway was washed away; the reason he ended up taking out such a huge part of the reverse mortgage he took, way more than he should have, was two-fold: he didn’t ask for help, financially or otherwise, and he tried his best to help us when he could which was mostly to help with the expenses involved around the kids’ extracurricular activities. I have hustled hard ever since my youngest child was two-years-old to make my dream to be a writer and a teacher come true. But I’ve been working as either an adjunct or an independent contractor, and I just can’t keep up with it like I used to AND tend to my own writing, let alone my own mental health or my chronic pain condition, especially when compounded by the mourning I’ve been handed too many times, too close together. This will allow me to supplement the mortgage and teach less. Teaching less means I can be a better teacher and make more room for my own writing which will also make me a better teacher. But most of all, knowing that I won’t have a landlord decide they need to sell again or that the kitchen needs to be redone to do a hideous job (where I live now they remodeled the kitchen, I guess, but despite putting primer on the walls, they never actually painted them, just put in all the cabinets, during Christmas no less, and because the counters weren’t installed properly, all the tile cracked within months from regular kitchen use!).

The truth is despite this kitchen or the twenty-five-year-old carpet, I LOVE this old farmhouse I’ve been renting for sixteen years, but the rent has literally doubled in that time. Some of my happiest memories live in this house, and while they also live in me, I believe places are “haunted,” not necessarily in bad ways, but they do possess the past, serve as canvas for our memories to play out upon). There is a memorial garden we planted outside Kaya’s bedroom window. There is the fact my dad died in this house or the wake we had for my husband where we sat with his body in the living room for three days and three nights as home funerals are our custom. Every night when I go to bed and every morning when I wake up, I see him kneeling there by the bed telling me, “I need to go somewhere.” I’ve had so much anxiety about what my life will be like next that I can’t just sit here with the pain of losing him. I think this move and change will help rip off the bandaid of holding on to what no longer is as I know I will never let go of him but if I can’t stay in this house and really make it mine, I need to go (and because it’s owned by Open Space, it can’t be sold). While I will clearly need to focus on getting this retreat up and running (I already have people interested), I will have the mental headspace to grieve because I will know, as much as we can ever really know, what tomorrow looks like, where I am headed, as opposed to having been absolutely consumed for half a year with the question: What do I do next? repeating in my head, again and again and again.

I have taken a lot of risks in my life, ones that are much bigger than most people feel able to do (and ones that are insignificant compared to what some people do). But every single time I really went for it, really pushed away the doubt and anxiety, it worked. It’s been when I’ve only half-assed it that it hasn’t worked out. One of the major breakthroughs I had when writing my first novel FIG was that my writing teachers were wrong. I’d been told over and over again to never “break character.” But when I had one of my characters react to a difficult situation in a way no one expected to her (including herself), she changed for the better. She went from being what I thought was the antagonist of the story to being my favorite character, and not because she’s a character you love to hate, but because she changed as a result of breaking free of her patterns; because she changed, so then did the characters around her, including the protagonist. When I stepped back to really contemplate this, I realized that in real life we “become” when we are either forced out of our comfort zones by circumstance or because we choose to take a leap. I am taking advantage of being forced out of my “normal.” After losing almost everyone in my family but for my darling Story, I have to take a leap of faith. I haven’t done this forever. I’ve been paralyzed by the PTSD. I’ve been paralyzed by grind culture. But the truth is I took the most creative risks when we were on food stamps. I used to feel so guilty spending money on writing contest fees, usually $15.00 a pop, but had I not done this (even if it meant sometimes the balance in our bank account dipped below zero), I would not have been discovered by an agent (this is a very simplified version of what really happened but if you want to know more google my name and Writer’s Digest for the story there).

![]()

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I think I already mostly answered this question in my really long answer to the last question, but I will say that I am not ignorant to the privilege I had growing up in a bookstore with parents who literally worshipped at the altar of literature. We might have been broke most of my childhood, but unlike everyone I went to grad school with for writing, my family supported my dream to write whereas their families were horrified by the choices they were making. My parents met at the esteemed Iowa Writer’s Workshop in 1969 waiting in line to meet their advisor Richard Yates (REVOLUTIONARY ROAD). My mother who was six years older than my dad was recently divorced and had come to the writing program because her mother didn’t fully understand it was a writing program and agreed to pay the tuition hoping she would find another husband. My mom had suffered from pretty severe agoraphobia for about two years where she couldn’t leave the house at all, and this contributed to the divorce, which then forced her to not only leave the house, but to really leave. My nana did get her wishes granted considering my mom did meet my dad, and right away, but I don’t think my grandmother had a younger man with no money in mind! My dad was doing everything he could to avoid Vietnam and had just returned to the states from Turkey where he’d been stationed as a school teacher for the Peace Corps. In the end they didn’t get their MFAs because my dad was scared of getting drafted so they moved to Ithaca in case they had to flee to Canada. He wasn’t drafted, they didn’t run away to another country, and while they were in Ithaca, they realized there was a niche market for detective fiction and murder mysteries after doing their best to make ends meet going to rummage sales to buy books, art, and antiques to resell. While they were at Iowa, and despite getting to study with Kurt Vonnegut or read the rough drafts of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories, they learned they didn’t really have what it takes to dedicate themselves to the craft of writing. They ended up at more parties than at the typewriter. They ended up reading more than writing. So they decided to dedicate their lives to supporting authors, which meant they got to keep attending parties and reading all the time, and they more than succeeded at this mission having won countless awards for their contribution to the book world.

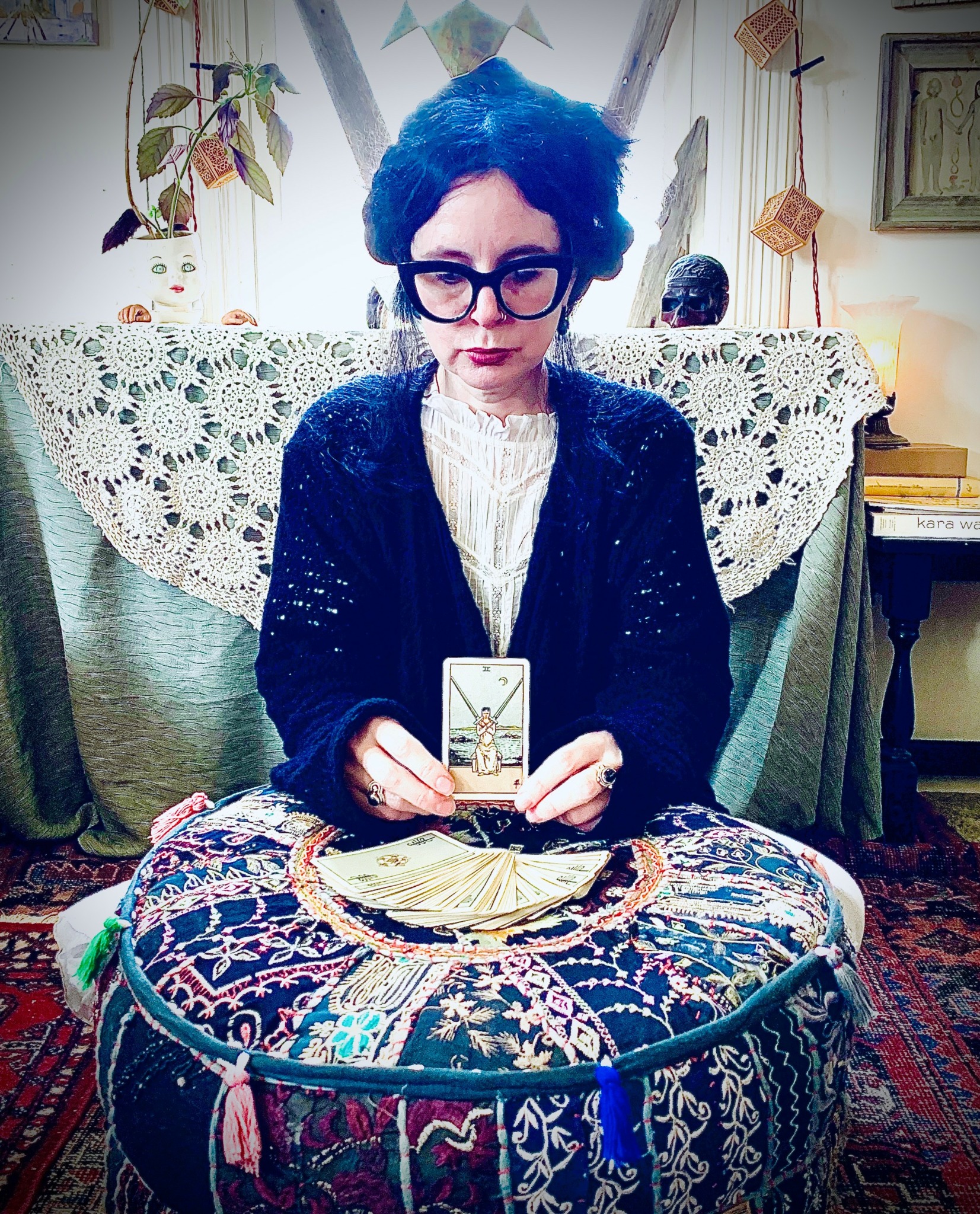

While I appreciate many aspects of what is known as The Iowa Workshop model, I also think it’s designed by straight white men and isn’t conducive to everyone, especially those of us coming from marginalized identities and experiences. As much as I adore the writing teachers I’ve had, they were very hands off, and I often felt neglected (especially considering the hefty price tag of an MFA even if I was mostly fully funded via grants, scholarships, and fellowships). I aim to be the teacher I wished I’d had. This is why I call myself a writing midwife. I midwife the process as holistically as I can. I get to know my students, not just their work. I try to make sure the relationships we form are long-lasting and have really come to consider many of them actual family which helps considering how much family I have lost when I didn’t have much to begin with anyway. When I was at Naropa in the MFA program I was introduced to Selah Saterstrom whose writing is as exquisite as she is, and she is the one who gave a name to a methodology I’d always used for approaching the page, “Divinatory Poetics.” This also gave me permission not only to talk about what I did and still do, how I use Tarot and other oracular strategies to create, her pioneering work gave me permission to develop it as a pedagogical tool a lot of writers resonate with (including many who are very hesitant at first to do something so “woo-woo”). The Tarot, oracle cards, and other forms of divination such as reading tealeaves or throwing the bones, simply tell you what you already know. Or they help you take risks by going a direction you wouldn’t normally try. Other than that, my very hands on and motherly/midwife approach to teaching and editing, is something that attracts my students and mentees. I am also a very skilled developmental line editor, excellent at helping a writer find the perfect title for their work, knowing how to help them do the writing THEY are doing rather than trying to make them sound like me or another writer that isn’t them (the shorter way to say this is that I help them find their voice, then use it). My history of trauma (which also includes sexual assault, domestic violence, a bad car accident, a chronic pain condition, and years of enduring the violence of poverty), makes me even more empathetic than I think I was naturally. And I do think my work as a witch, my ability to manifest, is inspiring to others. I can role model to other women writers dealing with PTSD that they too can survive.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

I think I have. But I will say I am tired of the emphasis on “resilience.” The fact our culture puts so much emphasis on “resilience” only perpetuates the problem that is people needing to be so damn “resilient.” We need to put the myth of the American dream to sleep, once and for all. It was only ever a potential for white men and that was a long time ago because even a lot of them, if they don’t come from money or are queer or disabled, have to hustle to survive too. The American dream is a lie. This whole pull yourself up by the bootstraps is problematic as a lot of people don’t even have the boots to begin with. In one of the grief support groups I’ve been attending we were given a worksheet where a list was provided of the cliched statements people often to say to people who are bereaved. On this list were the typical statements such as “He’s in a better place now,” and then a translation of what the person is really saying whether or not they realize it. I’ve been told over and over again how strong I am or that I just need to be strong, and this was on the list, and I was so relieved to see it there because it bothers me big time. First of all, I am tired of being strong. I don’t want to be strong. I would love to just fall apart so I can really feel my feelings and then actually process them. The translation for “You’re so strong/You need to be strong” is “I can’t do anything to help you right now/You might just be ruined.” I highly recommend looking into Tricia Hersey’s work on how rest is the real resilience we need to practice. Look into The Nap Ministry. A big reason I am about to take this major risk is because I am trying to find a way to take more time off, to rest, to heal. If I can do that, I will be a better and safer citizen (think about all the people driving around exhausted by grind culture and how dangerous the roads must be as a result! Think about all the people like my husband who end up having a heart attack and dying young because they worked too hard and too much for too little). We need a society that takes care of its people. We need to stop worshipping at the altar of “resilience,” and start bowing down to self-care which is also community care because if I can take care of myself then I am better able to care of you (and I promise I will).

Do you think there is something that non-creatives might struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can shed some light?

I spoke to this earlier in one of my other answers, but I think we artists today need to learn how to ask for help and accept it. I ran away from home when I was fourteen (while my parents were incredibly supportive of my writing, we had a lot of conflict in the home I won’t go into out of respect to them, plus I lived in Boulder during the 90s when it was very normal to see runaways and other vagabonds dreamily traveling through town on their way to an anarchist gathering or to open up a new squat in Philly or just to see the country and be here now). I remember hitch-hiking through Idaho and this trucker had picked us up. My boyfriend was asleep in the little bed most big rigs have in the back, and I’d helped keep the guy company as it’s a lonely job to drive cross-country all the time. When he dropped us off, before my boyfriend woke up, he handed me $100.00 which I tried to politely refuse even though we didn’t have any money. He told me it was a gift for him to give me this gift and that it was rude to refuse him of that. I think of that every time I have accepted financial help (or other help such as time and energy) from people which is also one of the only reasons, despite working SO hard and SO much, I didn’t end up unhoused with kids. The cycle of poverty is vicious and nearly impossible to escape, but it’s because of the help from benefactors that I have escaped it (fingers crossed the new plan works out!). But I also didn’t receive it solely as charity (not that I personally have any problems receiving or being charitable). I was supported this way because people saw the work I was doing and knew that the $2500 I get paid for one 15-week semester class with 12 students in it whose manuscripts I have to read and grade numerous times is criminal. They know as an adjunct I have no benefits, no bereavement pay. They know that as a freelancer, I am unfairly taxed, especially because of the lower tax bracket I fall into whereas the uber wealthy get all the breaks. These people knew that when I got my advance for my first novel, the sudden and temporary jump in income as an independent contractor was so devastating tax-wise my family almost ended up on the streets, and I almost lost my passion to write entirely because the stress made it feel as if I’d been punished for succeeding. Even before the current grind culture we live in now, and the outrageously expensive cost of living, artists have relied on benefactors for time immemorial. I’m lucky I lived on the streets and in the squatter community when I was a teen and young adult because I not only learned the value of Do-It-Yourself, I learned that D.I.Y. culture is really Do It Together, Be a Community.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.SarahElizabethSchantz.org and www, writesofpassage.org

- Instagram: Anangka

- Facebook: Sarah Elizabeth Schantz

- Twitter: Storymama3

Image Credits

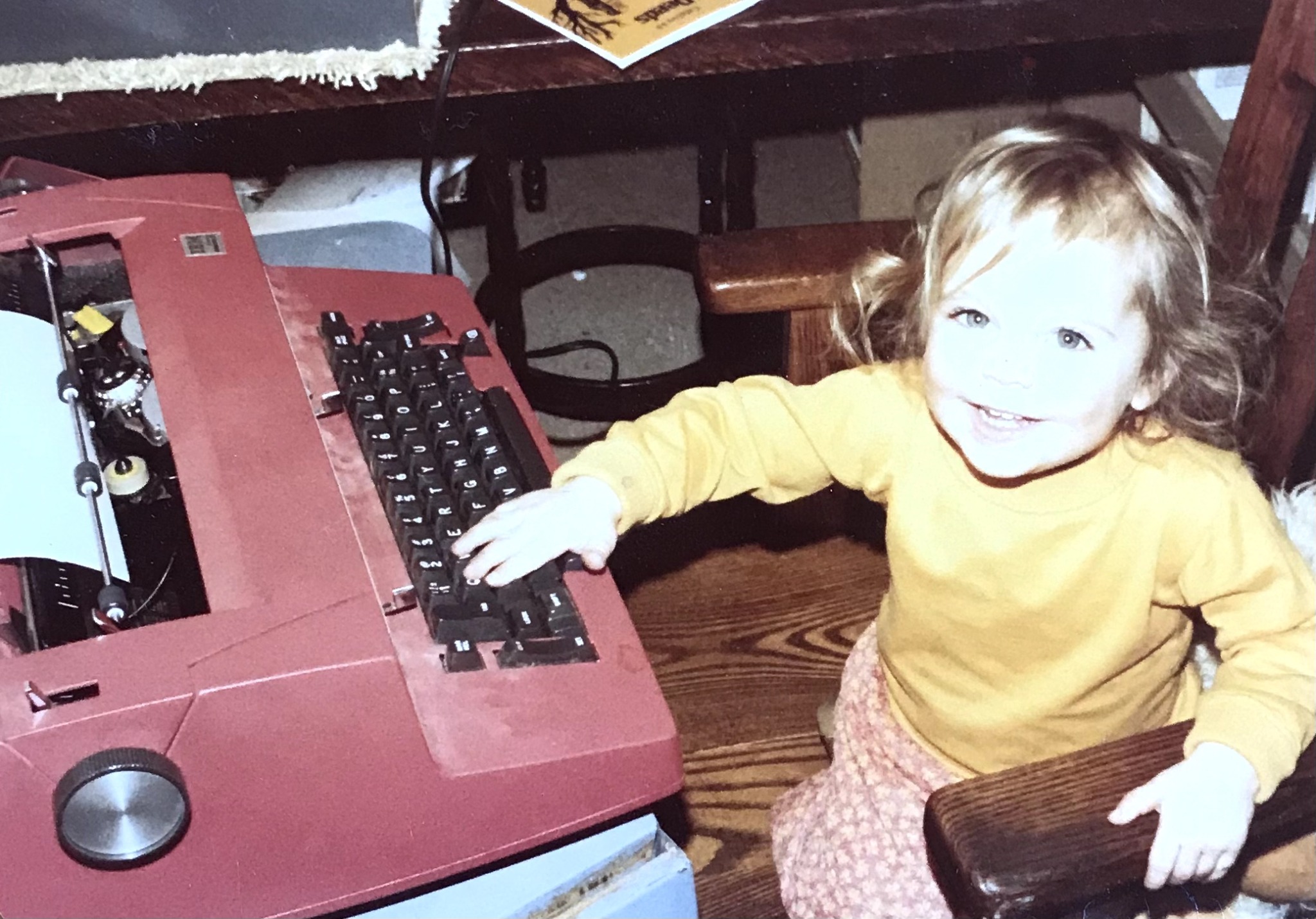

In the first black and white photo of me credit should go to Natalia Gaia. The one picture of me in a dark room in a white dress at a microphone should go to Mairead Case. The one of me reading Tarot cards and another with me standing next to a chalkboard with my name on it outside a bookstore should go to Story Anangka Fisher. And me signing stacks of books goes to Rozie Vajda. The others are really just personal photos.