Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Rudy Salgado. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Rudy, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you talk to us about how you learned to do what you do?

I learned what I do by paying attention to what I felt excited about, and finding the people who could help me learn how to do it. In my early twenties, I was working construction jobs and realized I really liked working with my hands. Art wasn’t something I did growing up, but my dad ran a denture lab and I grew up seeing a high level of craft and precision at his lab in our backyard. My first art classes were at community college and I fell in love with printmaking and ceramics while working on my BFA at Chico State. I loved the precise recipes and procedures for glazes, firing ceramics, and printmaking processes. I loved the long social history of both media – they both held pivotal roles in human civilization. I didn’t think about doing wet-plate collodion photography (tintype) until a few years after I got my MFA, when an artist at a residency program mentioned that if I could make a stone lithograph, I could make tintype photographs, and people would actually want to buy those. It’s funny, I had business ventures as a kid growing up, like selling Blow-Pops for 25 cents, and felt very proud and serious about being organized and making money. My MFA project was kind of a spoof on these ventures – I performed as Dr. Buttzer of Bubbleguts Enterprizes, a quack doctor diagnosing and treating ailments with colorful tinctures. Dr Buttzer’s office and laboratory featured huge collections of medical and plumbing supplies, all displayed and tagged like a natural history exhibition. Art school taught me just to think big and make lots of work, do things for free (exposure), and not to worry about the money part – galleries and collectors would come. Of course this is not the case for so many artists – we have to pay bills and still have time to make work.

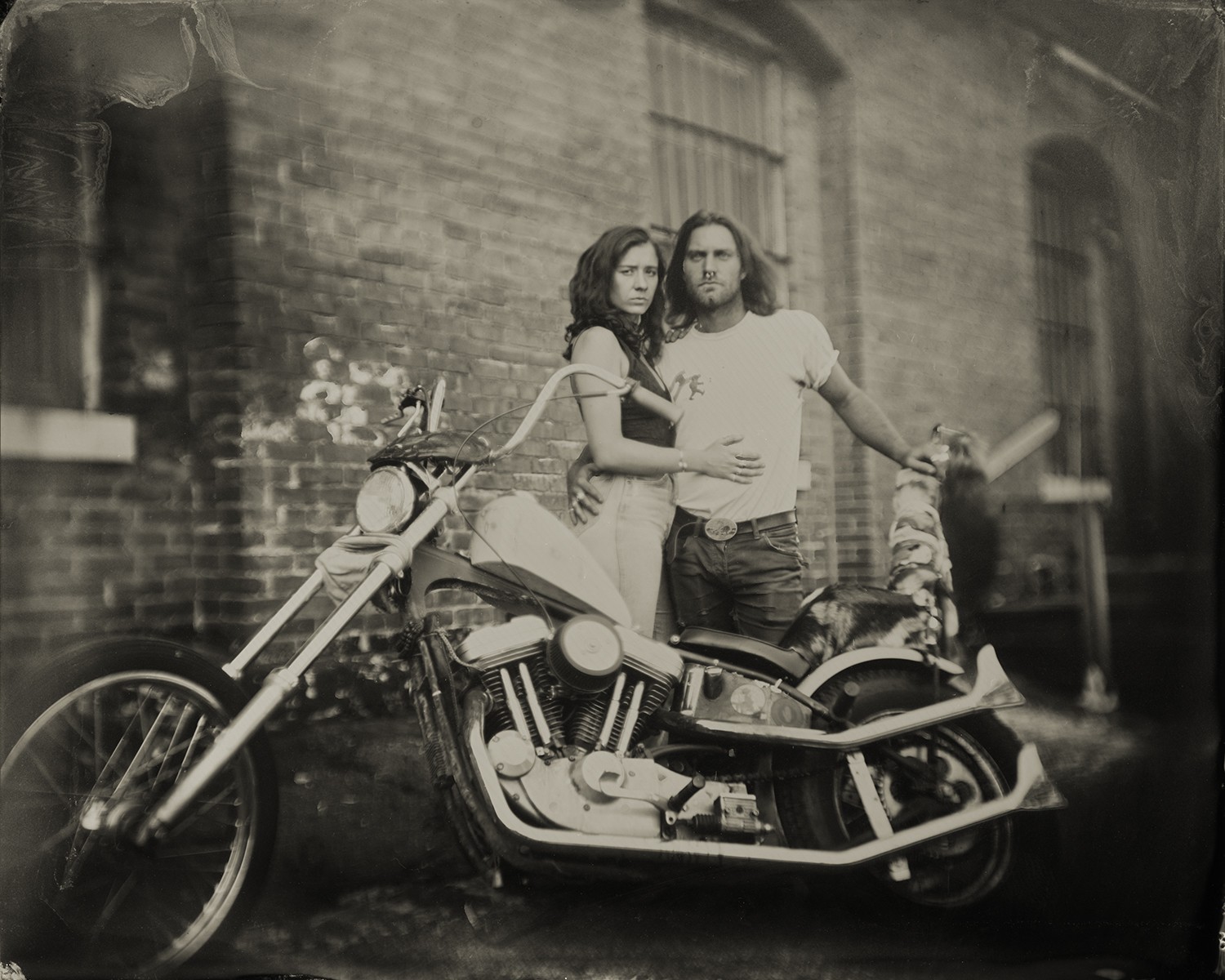

I really wish I’d started tintype earlier, since it checks so many boxes for me for the roles I like to have as a creative person. Tintype is an early photographic process invented in 1851, and for a long time it was conducted by traveling tintypists who worked out of mobile wagons and train cars, spending time in remote communities and even at war making images. In a lot of ways, the tintype process – practicing and mixing my own chemistry and then performing a very labor-intensive, pretty magical process for viewers – relates to Bubbleguts Enterprizes. It’s inherently social, I get to teach the process to people and get to know them. We have laughs and I’m providing a service. I get to play the character of a tintype photographer with a large collection of antique tools, lenses, and recipes at hand. Sometimes I get invited to make tintypes at living history events and reenactments, where people are really experts in the clothing and poses of the tintype era. Other times people use tintype portraits as a way to document important moments – everything from a pregnancy to gender transition or marriage. Tintypes are unique photographs in that there’s no film involved. They’re heirlooms and literally last forever – that’s why there are so many in antique stores and attics today. Digital files may disappear but someone 150 years from now could totally come across a tintype. There’s a weight and seriousness to them, like holding someone’s history in your hand, and people really seem to like that. Sometimes a tintype exposure is 20 seconds long, which results in a very different kind of portrait than an instantaneous iPhone photo.

When someone comes for a session I coat a plate by hand, making it light-sensitive, then load it in the camera, make the exposure, then bring it into the darkroom to develop. I get to show the whole process start to finish. I love teaching and history, so using the tintype process to engage both was a big “ah hah” for me. Like with printmaking, I’m using antiquated processes that could otherwise be lost to history. And though the plate itself offers a new way for people to really dig in to the materiality of photography (during an age where we all have 20,000 digital photos in our pockets), tintypes also have a broad reach on social media when people use them as selfies or headshots.

If I would’ve had a better understanding of what the working artist’s life is like, I would have been more prepared. The title “artist” is so broad – people call their 8 year olds “artists” and in some cases I think they might be the happiest ones around. I’m an artist now, but I’m also an educator and many other things. I moved to Louisville, Kentucky in 2012 to start a printmaking studio Calliope Arts with my partner Susanna Crum, who is also an artist and full-time educator. Calliope offers a space for artists to come and make print-based art like woodcuts, etchings, lithographs, and screen prints. We often work with artists to help them realize their own projects, and it’s a labor of love that makes a bit of money. We wanted to make our space in a place that needed us.

If someone in undergrad had told me “You’re going to have so many jobs, and that will be okay” that would have helped me. It’s been hard to measure success as a working artist. And with that, a sense of purpose has always been a little murky. I feel privileged that I get to make art, but also a little selfish if I’m not sharing it with others. I’ve had my work on display in a museum alongside some of the greatest artists in the 19th and 20th centuries. But even then, landmark achievements and benchmarks may not feel like “I’ve made it.” In a society where it’s so hard to exist with the necessities of living, Calliope offers a space to people who want to use it. I’m giving back. I have a lot of respect for people who design their own lives and live alternatively and define their existence through the way they live. Their actual living space, or lack of one. Or the things that people do to survive or make a living, balancing between the things that you have to do (like get healthcare) versus the amount of hours you can work for someone else.

Time and resources have been obstacles or delays in my learning process. An essential skill to overcome this was to learn from and work with other artists. Throughout my time in school, I always went to summer workshops like Frogman’s Print Workshops and residencies like Watershed and Penland School of Crafts. When I decided to start tintype in 2018, I did a workshop with a tintype artist in Oxford, MS to see how he organized his studio, what equipment I’d need to have.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I grew up in a live/work household, where my mom and dad ran a denture lab in a building in our backyard. At a time when people talk a lot about work/life balance, I always had this kind of flowing around – like my parents’ work was more part of our lifestyle than something that turned off at dinnertime. Their labor was evident to me throughout my childhood. I was the first person in my family to go to college, and had the privilege to choose art as a major. My parents were supportive of this. They taught me to work hard and that even if you don’t have a lot, you should keep it nice, clean, organized, and be proud of it. When you’re a working artist, you’re your own business, no matter what you’re doing, and the advantage and disadvantage is that you have to define that yourself and educate people about what you do and why it’s valuable.

I’m also really interested in other people, so I love the social space of the tintype portrait session. I love learning people’s stories, I think I make people feel comfortable to be themselves, and I also like having a job to do while we talk instead of just sitting around. For the past ten years my partner Susanna and I have lived in an 1880s brick duplex, with the Calliope printmaking studio and River City Tintype on the first floor. In the era in which it was built, many people lived above their storefront businesses. I’m interested in the return to that style of living as an artist. Our building did not have heat when we first moved in. Now it’s much more comfortable, but we’re still going room by room, space by space, making it better and more useable for us. We have a huge kitchen garden, chickens, cat, dog, plant nursery in our cellar, plus the two studios. I’ve done some urban archeology in the backyard, digging up a lot of antique hand-blown glass bottles and artifacts (read: “trash”) from the 19th century.

Our building is like a big sculpture, the longest art project of our lives. Work is slow because we do a lot of the renovation work ourselves, when we have money and time to make things happen. My partner Susanna, for instance, has learned how to restore and rehang 140 year-old windows with cords and weights. The building was built before electricity and plumbing, and there are transom windows above all the doors so the house can breathe on its own in a way that modern homes don’t. So we’re always thinking about the best way to live in that space, in a way that balances history, sustainability, and a reasonable level of comfort. A lot of people have been involved in our work transforming the building, with friends who work in the trades to our inventor/problem-solving artist pals.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

I feel like our building – with the studios, garden, animals, and our home – is a creative ecosystem of its own. And because of the studios (tintype and printmaking), we get to open that up and share it with people. Invite them to work with us on projects, or help them come up with ways to make their own projects happen. I think it thrives because there’s space, tools, and resources to try things out, to fail and try again without threats of huge investment or loss. The usual obstacles from idea to execution are more permeable, flexible in this kind of environment. I want this on a larger level for communities, particularly in Louisville and other cities in the South and Midwest (Louisville’s kind of both). Making creative work is a leap of faith and requires sacrifices and risk. A thriving creative ecosystem is one with an abundance mentality – in which artists and makers support one another with genuine curiosity and enthusiasm, and aren’t driven by competition or comparison. Creative people need time to make their work and places to show it, and it’s the community that benefits and gives feedback, and thus keeps that loop going.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

I’ve had to unlearn the “Always say yes” mentality. When you’re young, you try to be helpful and not miss opportunities. For exposure, or for the chance of a future opportunity or connection. At some point you realize you’re beyond that in your career and have to learn how to say no to things. It’s kind of a wager: you think about the positive aspects of the situation and who you could meet or what you could potentially get out of the situation. Even if it’s just happiness. Thinking about amount of time, energy, cost to participate. You just have to bet on it, but also remember that what you say “yes” to means a “no” to something else because of the time involved. As far as a backstory goes, I learned this over years of planning projects for “exposure” with people. It takes time and experience to figure out what you want to do for your own growth, rather than just for the satisfaction of meeting other people’s desires or expectations.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.rivercitytintype.com

- Instagram: @rivercitytintype

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/rivercitytintype

- Other: linktr.ee/rivercitytintype

Image Credits

Rudy Salgado and Susanna Crum