We were lucky to catch up with Robert Sherer recently and have shared our conversation below.

Robert, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today When did you first know you wanted to pursue a creative/artistic path professionally?

A. I have been a prolific creator and nature lover since early childhood but I seldom ever thought about the visual arts as a viable career path. I had always thought of art schools as exclusive playgrounds for rich kids. I mostly made images as a matter of Automatist Therapy. By the time I got to college I had convinced myself that Botany was the path for me. During my studies, I made hundreds of botanical illustrations in sketch books, images of observed plant structures and of Surrealistic, speculative plants.

My Aunt Shirley was a sort of Auntie Mame character in my life. She was well connected in academia because she worked for Georgia State University in Atlanta. She loved my plant drawings and asked me to come visit and to bring my sketchbooks to show one of her friends. So, I went to Atlanta and we went to lunch. When I had finished showing the drawings to her friend, the woman informed me that she worked for Atlanta College of Art and would like to offer me a Ford Foundation Scholarship to study art there. All of a sudden, my whole life made sense to me. I knew that I would never be happy in any career path other than Art. Without hesitation, I told her that I would be honored. I did not cry while with them – I waited until I was in the car heading back home to close out my old life in Botany. Aunt Shirley had tricked me into seeing my potential and she had even cleared a pathway for me into the art world.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

Q. How did you get into your industry? When I arrived in Atlanta in the late 1970s, the city’s cultural scene was burgeoning. There was a rebellious underground art scene, punk rock scene and gay scene. (Atlanta was, and still is, a haven for progressive Southerners seeking an escape from their hometowns.) I jumped into the middle of it all, feeling the need to catch up for all of those lost years. I created and exhibited my off-beat works of art. I participated in poetry slams. I protested and joined activist organizations. My work began to be recognized by art galleries.

Q. What type of creative works do you provide?

A. Through the years, my work has changed several times. My oeuvre can be divided into four distinct bodies of visual inquiry: (1.) the Censored Male Nudes (1989-93); gender reversals of famous sexist paintings from Western art history, (2.) the Neo-classical Works (1993-98); the spiritual journey of my feminine consciousness, (3.) Blood Works (1999-present); botanical drawings in human blood exploring race and sexual politics, and (4.) the American Pyrographs (1999-present); wood-burnings on veneer, scenes of gay teen romance. An archive of significant works from each of these periods can be found on my art website: http://www.robertsherer.com

Q. What problems do you solve for your clients/collectors?

A. I’m not sure if I solve any problems for my art viewers or collectors, but I do give them permission to feel, to be moved by the experience of viewing art. My art is activism. It confronts social concerns and injustices so there’s going to be some tears shed by people who can still feel.

My Blood Works paintings, especially the ‘Love and Loss in the Age of AIDS’ subseries, frequently touches people who have lost loved ones to the epidemic.

For some people, my American Pyrographs series provides some healing strength because the series attempts to sew the experiences of LGBTQA+ youth back into the fabric of Americana.

Q. What do you think sets you apart from others?

A. My willingness to confront uncomfortable issues, social ills, with visual art. I grew up in a suffocating small town where there were lots of “things not to be talked about.” When I moved to Atlanta, I kicked the closet door off of its hinges so hard that it could never to be used to imprison me again.

Q. What are you most proud of?

A. My liberation from my upbringing and the liberation I have mentored in others as an educator. I have been an art professor for 21 years at Kennesaw State University where I have influenced many students and the community.

Q. What are the main things you want potential clients/followers/fans to know about you/your brand/your work/ etc.

A. My art isn’t designed to match your sofa.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

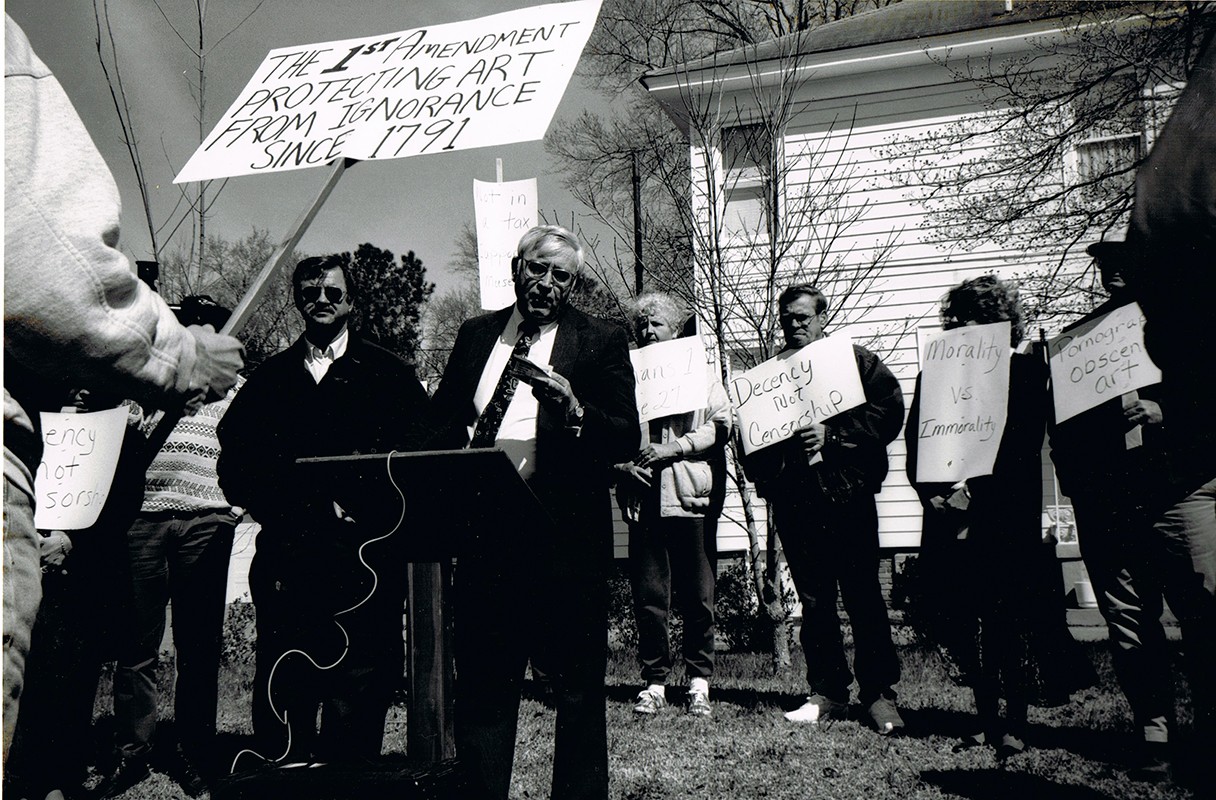

A. In the early 1990s, religious conservatives began using computers to organize their congregations and their efforts to impose Mosaic Law upon Americans. They took particular issue with my M.F.A. thesis exhibition titled ‘Re-Presentations’ because I placed contemporary men in reclining odalisque poses traditionally used by male painters to depict women as commodities.

Their nationwide campaign to censor LGBTQA+ art used the excuse that my artworks did not conform to “community standards”. They repeatedly protested and shut down my exhibitions stating that “Sherer perverts God’s natural order by placing men in women’s positions.”

From 1992-96, my exhibitions were censored four times. These attacks on my art were costly, complicated and the controversy oftentimes overshadowed the art. The American Civil Liberties Union and I were on speed dial. The primary thing that helped me to perservere and ultimately to prevail was my dogged belief that I was not doing anything illegal or immoral.

We’d love to hear a story of resilience from your journey.

A. In the mid-to-late 1990s, my art career was bustling. I thought I had it all. I had notability, critical praise and hefty sales. I foolishly thought that the more art galleries who represented my work, the more successful I was becoming. The galleries made it clear that they only wanted me to produce the kind of art that my reputation was built upon. The act of painting felt like self-parody because I was copying the style of myself. At one point, my work was represented by seven galleries. It was like having seven jealous bosses always demanding that I send them more product. In 1999, I had a meltdown and called all of my dealers to inform them that I would no longer be creating large figurative oil paintings. It proved to be the best career decision I ever made because it freed me to make authentic art again.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.robertsherer.com

- Other: Google my name.

Image Credits

Morgan Eubanks