We recently connected with Robert Dick and have shared our conversation below.

Robert, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. Can you tell us about a time that your work has been misunderstood? Why do you think it happened and did any interesting insights emerge from the experience?

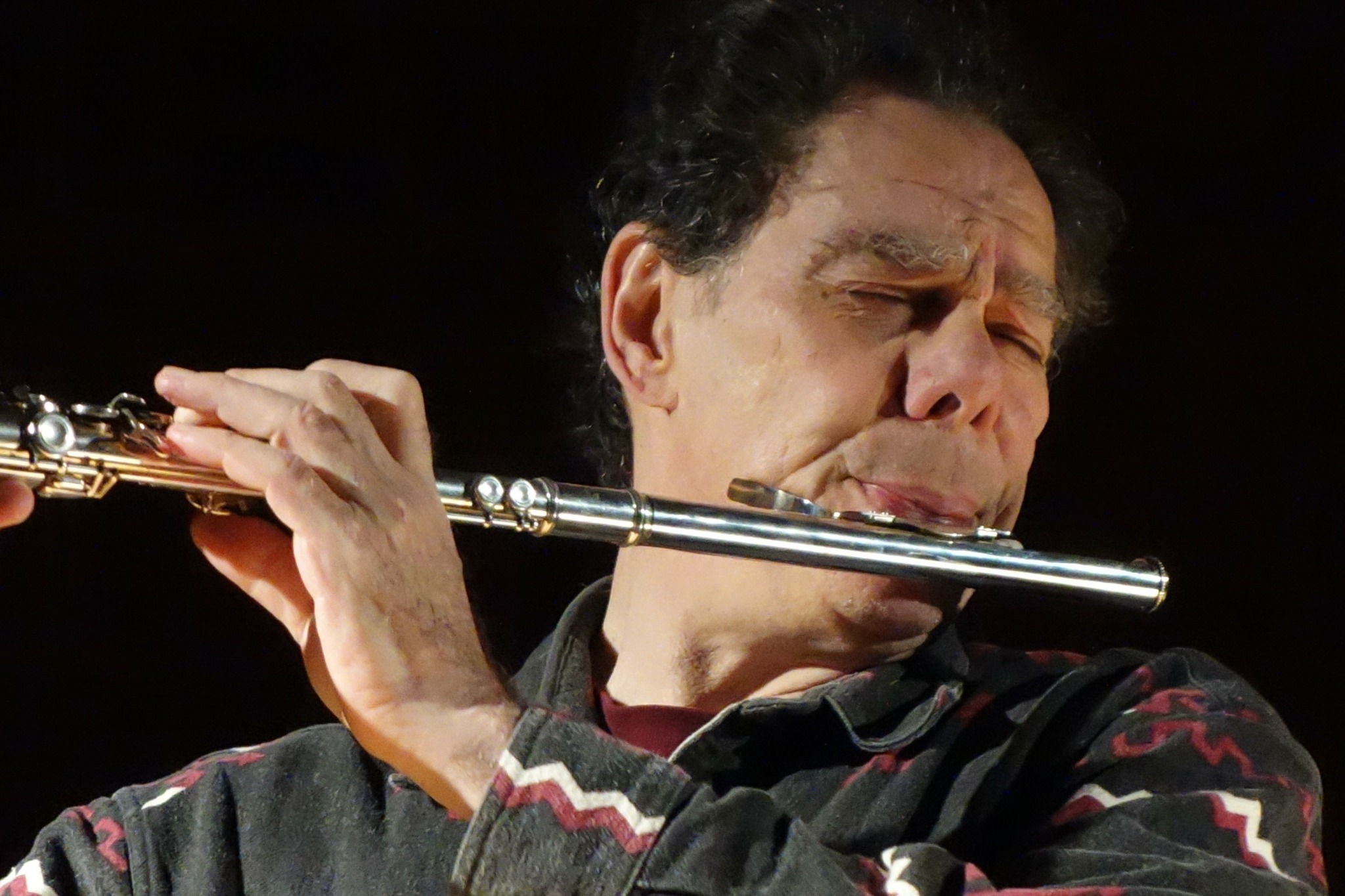

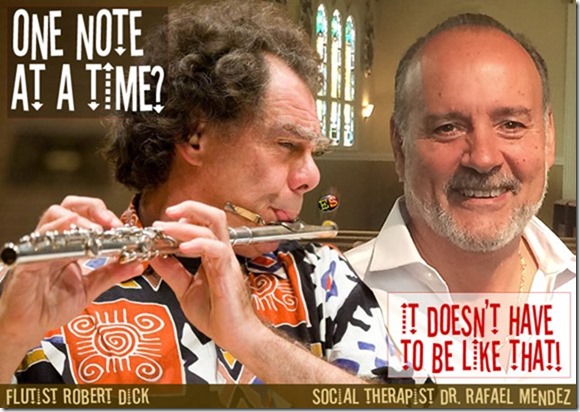

I have invented an entire glossary of new sounds for flutes, often playing multiple notes simultaneously rather than the traditional one note at a time. Using the sounds I’ve invented, I’ve been able to create music that is truly new. An issue that has cropped up throughout my career, however, is that listeners can get caught up listening to the sounds rather than the music that the sounds convey. When I first started playing solo concerts, I frequently had the experience that, although I played my heart out, the audience didn’t really connect.

It hurt. And something was going on that I didn’t understand. So I asked the people who would know, the audience members who clearly weren’t into the music. They’re easy to spot from the stage. Due to the astonishing attractant power of free wine at post-concert receptions, I had the opportunity to speak with occasional audience members who I had noticed weren’t into my performance. While sometimes very awkward, these conversations were revelatory! I discovered that, while I played, these folks were involved in an intense imaginary conversation with me; a conversation I had not been aware of. They were thinking things like “Why does this guy think I know this music? I’ve never heard anything like it before and am lost.” Before learning this, I had always thought that I was playing this cool new music so that people would have a chance to dig it. As a creative musician, I had forgotten (if I ever knew) how important familiarity is to most listeners.

I had to find the way to change “Why does this guy think I know this stuff?” to “I can hear that! Wow!” I began to introduce the music from the stage, something that never happened in the classical concerts I grew up with. I started to tell about the music and what is was meant to communicate, and I started to speak about my thoughts and feelings. And, as I became more better and more relaxed with these intros, I also discovered that I could be spontaneously very funny as well as very informative. For years now, my performances flow from the spoken to the played — sometimes overlapping! — and back. And people are getting it!

The Big Insight I took from this, and which I’ve applied to many things in life, can be summed up as “Don’t Assume. Ask.”

Robert, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

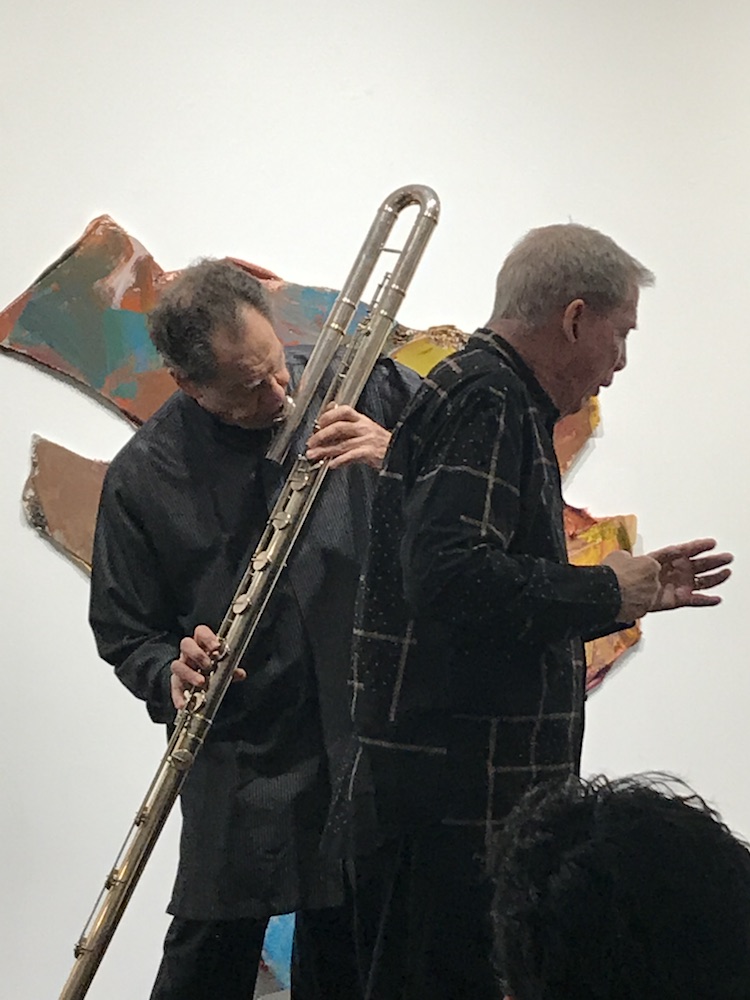

I’m a creative musician. I play my own music in solo concerts and I collaborate with other creative musicians, often improvising entire concerts. Flutes are my instruments, from the tiny (yet powerful) piccolo through the flute, alto and bass flutes, down to the standup contrabass flute. I’m known for the many thousands of new sounds for flutes that I have invented and the music that I have made that uses them. My approach to the flute (and to other acoustic instruments when I write for them) is that it’s a human powered synthesizer, capable of a vastly wider range of expression than its traditions dictate. My solo concerts have been compared to the experience of hearing a full orchestra.

I’ve always believed in sharing the knowledge I’ve discovered. To simply keep it all for myself, while easy, seems incomplete. My first book “THE OTHER FLUTE: A Performance Manual of Contemporary Techniques”, was published in my twenties, and it remains the standard work today. Going beyond the information itself, I’ve created a pedagogy to enable flutists to learn these new approaches and to help composers use them.

My best known invention is the “Glissando Headjoint®”, a telescoping flute mouthpiece that can be thought of as the “whammy bar” for the flute. I market these under my name.

How did I get into music? In my family, it was assumed that my brothers and I would play musical instruments. My mother was a classical pianist and piano teacher, and music was important in our family life. We attended a lot of classical performances, mostly pianists and violinists. For me, the question really wasn’t if I wanted to play music or not (and I did), but “which instrument?”. We had two kinds of music in our New York City apartment. Classical music and Top 40 AM radio music. When we kids were sick and missing school, we had an AM radio at our bedside. As a child, I heard the great pianists at Carnegie Hall and Little Richard on the radio. The first record I ever bought was “Good Golly Miss Molly”. And in the song “Rocking’ Robin”, I heard the flute for the first time. It was a piccolo, actually, but I didn’t know. The sound was magic and I wanted the instrument that made it. I campaigned for a flute and my parents actually listened. I came home from 4th grade one November afternoon and there was a flute teacher and a flute! I loved it and have loved it ever more deeply ever since.

Music is my life and passion and profession. I’m an independent soul, top to bottom. Along with the art, worked on daily for several hours, there is the business side; getting engagements, self-publishing, promotional work (which I’m terrible at), marketing the Glissando Headjoint® and lots more.

I began my career as a classical flutist, with an accent on orchestral playing. If you asked me at age 18 what I’d be doing with my life, I’d would have answered, with certainty, that I would be the solo flutist in a major orchestra. At age 19, I was the solo flutist in the best student orchestra in the US, the Berkshire Music Center Orchestra at Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony’s summer home. And during that summer, I learned that the orchestral path was not for me. I didn’t want to spend my life playing the same music again and again. And the conductor, waving a stick around, telling the musicians what to do, just had to go!

From that moment until now, I’ve been outside the institution, making my own way. I have evolved from a classical flutist to a flutist passionate about playing contemporary music composed by others, to someone who began composing and improvising in my twenties, to playing my own music virtually exclusively from my early thirties and on to the present.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

The most rewarding aspect of my artistic life is that I have enabled my inner child to thrive. The extraordinary flow and exchange of energies through music is something I live for. And, as I teacher, I get to help others to release their imaginations too!

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can provide some insight – you never know who might benefit from the enlightenment.

The struggle to understand each other goes in all directions. If I’ve understood the basic orientation of non-creatives, it is that their work is to provide goods or services that others already know they want. As a creative, my job begins with invention, coming up with new music or a new type of musical instrument — and with finding ways to publicize what I’ve created and to entice others into being involved.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.robertdick.net

- Instagram: fluterobertdick

- Facebook: multiple pages: Robert Dick; Robert Dick’s Glissando Headjoint®; Robert Dick Contemporary Flute Week

- Youtube: I have many videos on YouTube. Some are performances, some are instructional for flutists and anyone interested in approaches to learning.

- Other: Bandcamp — search for Robert Dick

Image Credits

1. Atterrormusical

2. Gwenolee Zürcher

3. Martin Phillips

4. ?

5. ?

6. Ben )’Brien-Smith

7. Simon Kim

8. Don Foresta