We recently connected with Rebecca Richardson and have shared our conversation below.

Rebecca, appreciate you joining us today. So, let’s start with a hypothetical – what would you change about the educational system?

If I could change one thing about the education system, it would be the way we train students in advanced STEM degrees. The culture of academia is diseased – obsessed with output, indifferent to growth, and blind to purpose.

This narrative played out constantly during my time in graduate school. Academia loves to push scientific excellence and innovation, but too often fails to support the very people expected to carry that vision forward. Adequate mentorship is treated like a bonus, not a requirement. Because there are no consequences for faculty who neglect, expl*it, or abuse their students, toxic and damaging behaviors go unchecked. Sadly, my experience was not unique. It reflects a deeper, systemic failure across academia. When talented and capable students are marginalized, excluded, or buried under unnecessary barriers, the entire scientific community suffers. Discovery depends on diversity of thought and experience. When that is stifled, scientific progress suffers. We lose the very innovation we claim to value.

If we want to prepare students for meaningful careers and fulfilling lives, we need to radically rethink what graduate education looks like. Academia has persistently upheld a culture that normalizes neglect and calls it rigor. This culture must give way to one that equips students to lead. That starts with creating environments where students are challenged through support, not neglect. Where mentorship is a standard, not a luxury. Where accountability is not theoretical, but enforced. And where scientists are valued not just for what they produce, but for the insight, experience, and vision they carry.

We cannot keep building scientific excellence on a foundation of silence, expl*itation, and burnout. Science is a privilege and a responsibility, and at its core, it is a service to humanity. When we fail to train and support the people responsible for carrying that mission forward, it is not only the scientific community that suffers, but also the well-being of the very people it is meant to serve. We cannot afford to keep losing brilliant minds to broken systems. If we want science to move forward, we must start by repairing the places where scientists are made.

Rebecca, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

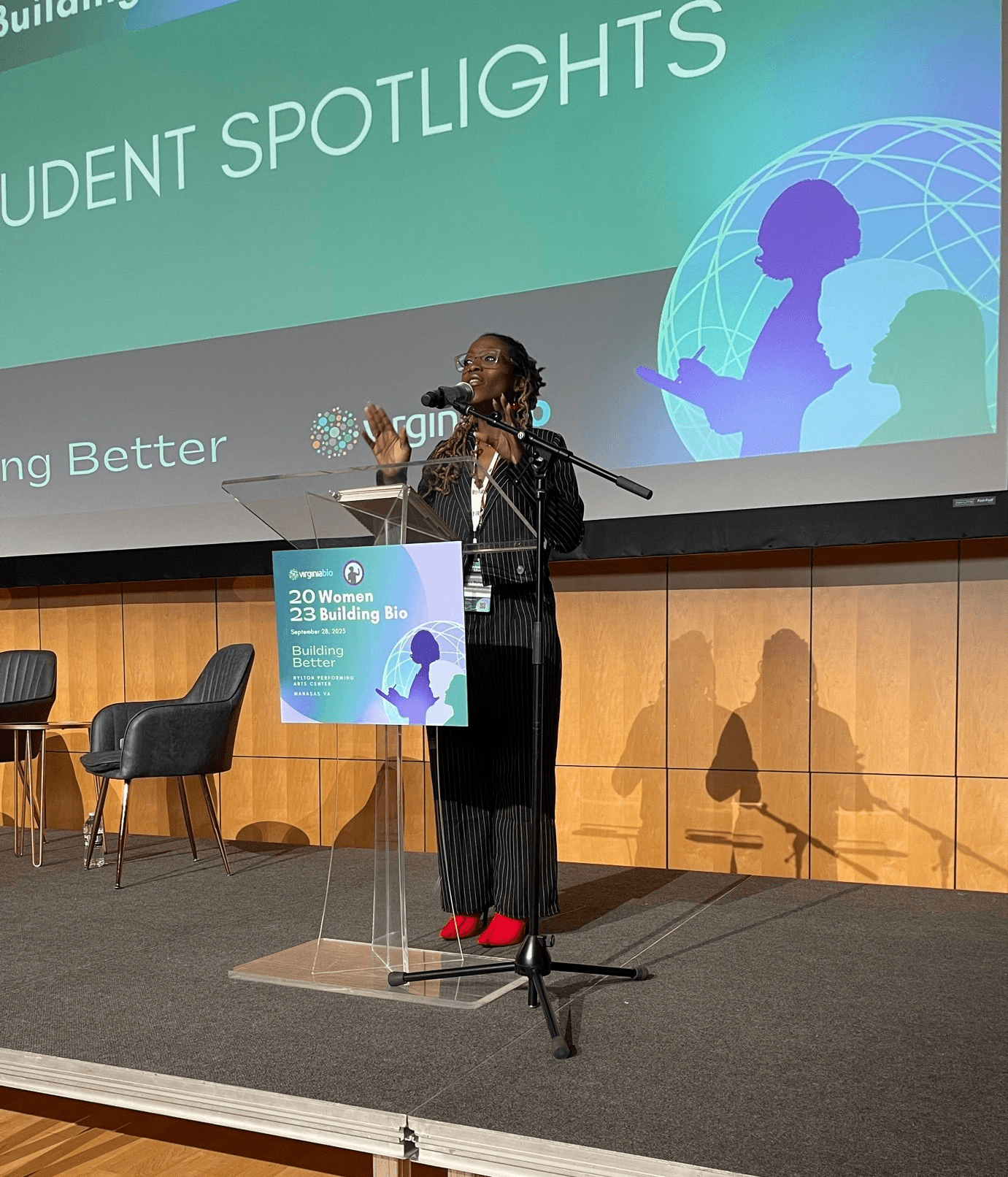

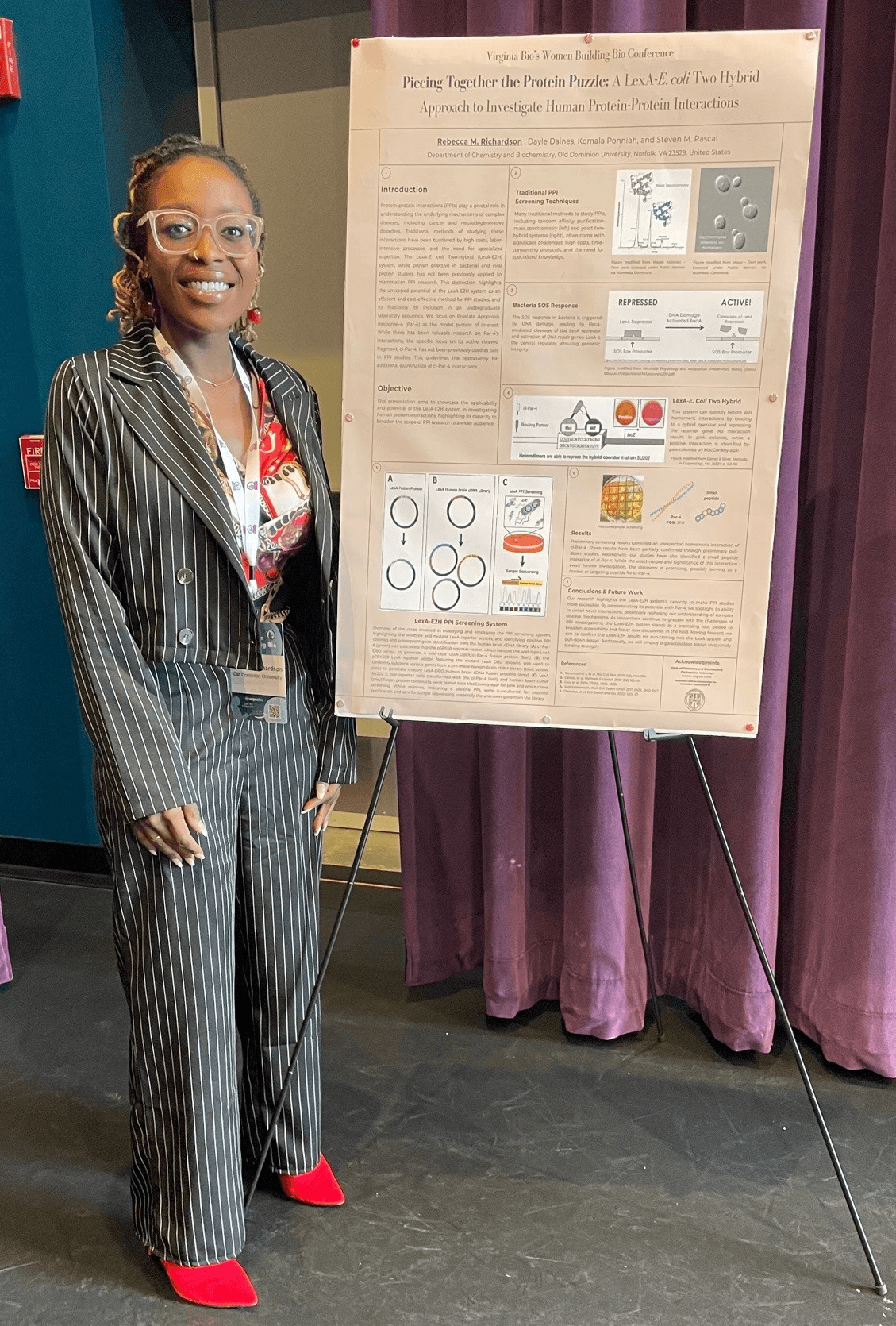

I’m a biochemist by training, a nonprofit professional by experience, and an aspiring biotech founder at heart. I recently earned my Ph.D. in Chemistry from Old Dominion University, where I studied how specific human proteins interact with each other in the context of diseases like cancer and neurodegeneration. My work focused on using a simplified bacterial system to explore these interactions in a more accessible and scalable way. Before that, I studied how silver nanoparticles affect cancer cells and whether they could be used safely in medicine. At the core of all my research is a drive to make science useful, not just theoretical. I want to help turn discoveries into real tools that improve people’s lives.

Beyond the lab I’ve spent the past few years supporting small business owners through my role at Black BRAND, a nonprofit focused on economic empowerment. That experience gave me insight that reshaped my understanding of what it means to be a scientist. Working with entrepreneurs, I began to realize that science is everywhere – woven into how we solve problems, collect data, interpret patterns, test ideas, and make decisions based on what we learn. Science isn’t just experiments and publications. It’s a way of thinking, a way of solving problems, and it belongs to everyone.

Looking ahead, I hope to build a biotech company that reflects those values, where integrity guides the science, people come before profit, and every innovation is rooted in service. I believe science should be ethical, intentional, and accessible, not just groundbreaking. My goal is to help develop tools and technologies that not only push the field forward but also honor the people and communities they’re meant to serve.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

One major lesson I had to unlearn is the belief that holding a PhD automatically means someone is highly qualified or an exceptional scientist.

When I entered graduate school, I had no research experience beyond the labs required for my undergraduate science courses. I assumed that anyone with a PhD was brilliant, well-rounded, and had mastered their field. I thought the title alone reflected deep intelligence and credibility.

As I spent more time in academia, I began to see the reality. I began to notice that not all PhDs were created equal. I saw PhDs earned through genuine hard work, creativity, and scientific integrity, but I also saw others who advanced through the system without the same level of effort, curiosity, or integrity. I witnessed how uneven the process could be. Some students had to fight for every step, while others were handed opportunities with little resistance.

A PhD is a title, not a testament to excellence. It does not guarantee expertise, curiosity, or integrity. What truly defines a scientist is the depth of their thinking, the rigor of their work, and the values they uphold. In the end, it is not the letters after a name that matter most, but the substance behind them.

We’d love to hear a story of resilience from your journey.

During my graduate studies, I had to start my research over not once, not twice, but four separate times. Each time felt like a gut punch just as I was beginning to find my footing.

My first lab dissolved without warning, forcing me to find a new advisor. In the next lab, I was placed on a project only to be removed from it without explanation. Then, on my third project, the instrument I depended on to collect more than two-thirds of my data broke beyond repair. Eventually, I landed on the project that became my dissertation, but each setback meant starting from scratch. Years of work vanished, never published or even acknowledged in my dissertation.

It was exhausting, frustrating, and at times utterly crushing. But from the moment I decided to pursue a PhD, I had made up my mind that the only way out was through. Quitting wasn’t an option because there was no plan B. I was determined to leave ODU with what I came for by any means necessary. I waged all-out war on every obstacle in my path. I showed up to the lab tired, broken, and worn down. I showed up when my body screamed for rest. I showed up through the doubt, the frustration, and the tears no one else saw.

Resilience, in my experience, is often painful, quietly endured, and rarely acknowledged. It’s the silent choice to do the hard thing day after day, even when the path is unfair, the obstacles unnecessary, and every step forward feels like a battle. This quiet but unyielding commitment carried me through graduate school and remains the foundation of my strength today.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://reberich.wixsite.com/becc

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/r-e-b-e-c-c-a-r-i-c-h-a-r-d-s-o-n-45a387175