We recently connected with Randall Flores and have shared our conversation below.

Randall, appreciate you joining us today. We’d love to hear about one of the craziest things you’ve experienced in your journey so far.

Having worked in Asia’s supply chain for twenty years, I’ve amassed quite a collection of unbelievable stories. During one instance, I cooperated with a factory in northern China that produced 125,000 pairs of shoes with defects. Despite attempts by my staff, they refused to stop and pressured my inspectors to release the goods. I had to fly there to reject them. The factory leadership tried to convince me to reverse my decision over dinner with multiple toasts using “baijiu,” Chinese grain alcohol. They even hired two professional drinkers to accomplish the task. One after another requested to finish a glass. After each, someone would remark, “You can accept the shoes, right?” or “They’re not that bad, yes?” It felt like they were Jedi mind tricking me, and I wondered how they knew how. In addition, I kept a bag of rejected production under my seat and took them with me to the toilet to prevent someone from switching them. They objected to my taking them and actively sought an opportunity.

The meal ended after three hours when the cook wanted to go home. Despite everything, I remained upright and exited, shoes in hand. The next day, I learned about the professionals, and the situation became clear. My team told me the hired drinkers visited the Emergency Room after dinner. That was surprising.

Ultimately, we bought the product at a discount, and my reputation for outlasting the “pros” always preceded me when I went to other factories nearby. They all wished to give it a try. I reduced my visits to survive.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

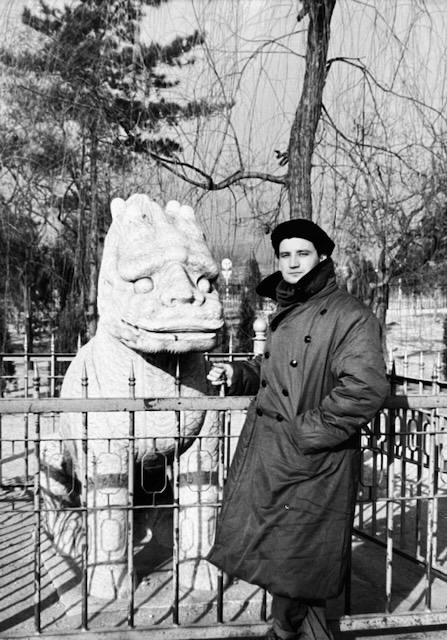

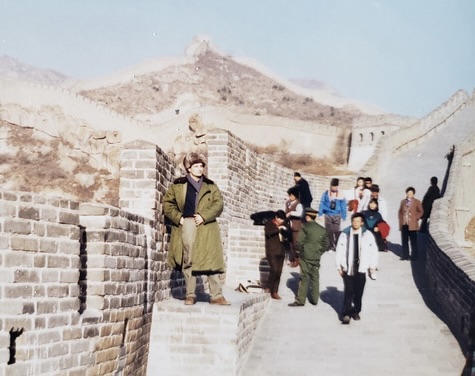

I began my career in 1990 when I studied Mandarin at Peking University in Beijing, China. I then worked in Taiwan until 1994, when I accepted a job at a shoe company on the mainland. Over the next decade, I traveled throughout the People’s Republic, establishing offices, recruiting and training employees, and collaborating with dozens of factories. In 2005, my company merged with another corporation, leading me to oversee manufacturing in seven countries and handle retail operations on four continents. I was on the move almost every day. Juggling diverse cultures and time zones made managing challenging. To handle everything, I relied on my laptop, cell phones, and Blackberry. It was the career I yearned for, and I found great pleasure in effortlessly maneuvering through some of the world’s busiest airports. As the Managing Director of Asia, I made extensive efforts to support and empower my staff, fostering their growth and success. In Asia, many employees stay at work well into the evening. I urged them to leave the office and cultivate social lives. This also increased their happiness, which is crucial in life. I moved back to the US in 2015, and even after ten years, I still hear from my staff in Asia, which suggests that I made a lasting impression on them.

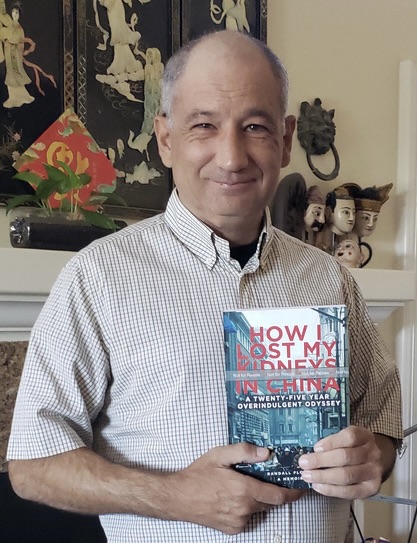

Because of my unconventional and remarkable career, I wrote a memoir called “How I Lost My Kidneys in China” and finished a screenplay based on it. Perhaps someday, I can bring my story to the silver screen.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

One of the hardest lessons I had to learn was that no matter how friendly a business partner appeared, there was always a possibility that may not be their true self. I often disagreed with factories, but we mostly solved these issues over long dinners followed by karaoke. Sometimes, the situation grew more intense. In one instance, I formed a close friendship with a factory owner, and we frequently had dinner together and went golfing. I thought we were good friends and could separate our friendship from business until one day, he exiled me from the factory for rejecting inferior product. They created the problems, but they took it out on me. A week after being banned, the owner called me to reconcile. I made him apologize to me in front of his staff before I agreed to return. We patched things up, and he even asked me to be the best man at his wedding. However, I never forgot how he treated me, and I couldn’t trust him again.

Do you have any insights you can share related to maintaining high team morale?

The best advice I can give is to always be aware of the working conditions and obstacles employees may face in the office and at home. By being attuned, you can lend a hand or ease their load until they find a solution to their problem. When you treat staff as individuals with personal challenges, you establish a connection that fosters appreciation towards the company. They will also be more productive when focused on the job. Employees value being part of a team that supports them, leading to a desire to stay with the same company rather than seeking alternatives. In my organization, we celebrated birthdays monthly, distributed bonuses, and arranged large group dinners for major holidays. The purpose was to uphold morale, especially during challenging times. It was also the right thing to do.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.howilostmykidneysinchina.com

- Facebook: Randall Flores the Author

- Twitter: @randallshanghai