We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Randall Fleming a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Randall, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Can you open up about a risk you’ve taken – what it was like taking that risk, why you took the risk and how it turned out?

As a zine publisher who by accident crawled into the mainstream publishing world, I got a bit too big for my britches after I — also by accident — cut my teeth as a tabloid newspaperman in NYC. Because I felt I could do most anything in the milieu of publishing, I jumped into the deep end of journalism by starting up my own newspaper a decade later. I had no concept of risk, and while that derring do served me well in the punk rock world of zine publishing, it was not appreciated in the larger world of politics.

I didn’t do it alone, however. I had a partner, an equally wild artist, poet, and writer whom I won’t name owing to my desire to protect her professional status. It was her idea to start a arts-based community newspaper with a firm perspective; it was my wild idea to make it a NYC tabloid-styled newspaper that took on the establishment of corruption emanating from the South Bay city hall where we lived.

In hindsight, I should have pumped the brakes hard before careening into that wildfire of newspaper war with the local paper that was secretly funded by city hall. The biggest mistake was the debut edition taking aim at the mayor and his cronies. Had we started out as a typical community paper that invited discussion, promoted events, and featured columns by long-time residents (which we eventually did do), we could have built trust. Instead, we created hard divisions. Although we were fighting a battle to expose long-standing corruption, we did it the wrong way.

I wouldn’t have not done that newspaper; if given the chance again, I would have done it a different way. We may have made a difference instead of leaving a bigger mess after the Morningside Park Chronicle was dissolved.

I’ve learned that it takes patience to fix things, and the bigger the injury, the longer the time required to heal it. I learned that I may never see the healing I hope to see done, and yet I nevertheless need to work toward that goal. Like the living root bridges of India where those who start weaving the roots rarely live to see the finished bridge, those who work toward any end may well never see it — but that is no reason to not do the work.

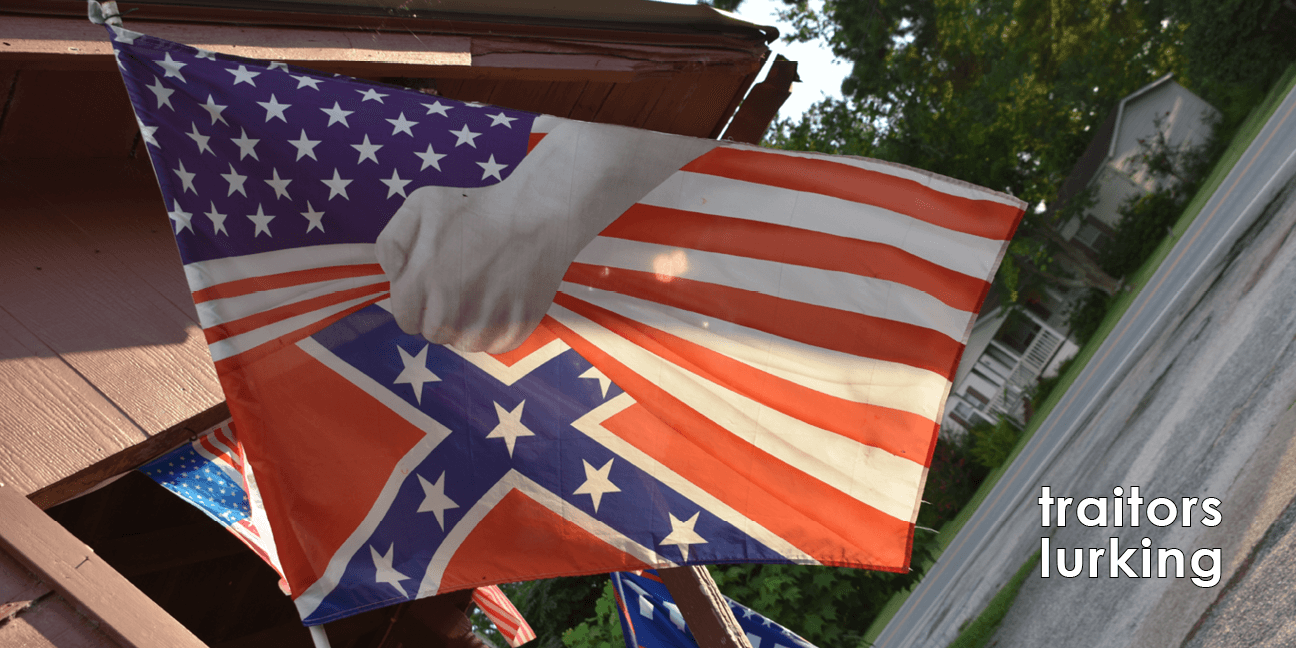

The risk I’m taking now, however, is altogether different — although I’m not being personally confrontational when accosted or wrongly accused of something. I know what I’m doing, I try to understand the people who are certain to be upset — even as they display the very flags I’m photographing — and I’m willing to stay the course. I’ve been threatened, harassed by cops, and even shot at as I took the images for this book. I won’t be deterred, and if something happens because someone wants to physically attempt to prevent me from documenting these flags and exercising my First Amendment rights, then that’s the risk I’m willing to take.

Randall, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I started my craft as a child in Montgomery, AL in the late 1970s. My folks were military, and I had lived around the world prior to being stuck in Montgomery; as such, I had been exposed to other cultures. To be sure, I was a pariah in Alabama. The other kids thought me weird (I was), and as I was taller than all my teachers, it was hard for me to hide. My first publication was a zine before it was called such. I was inspired by MAD Magazine. What I later learned was parody, satire, and surrealism was what I loved to convey in person and in print. My zine was a hand-drawn parody of Star Wars that mixed social commentary, surrealistic silliness, and goofy nerd jokes. I sold copies of it for $1. Each copy took me a few days to do as I literally re-drew each one. I didn’t have enough sense to ask if there was any other way. Sadly, I was in a town that was well behind the times, and had I known about the mimeograph or hectograph, I may have gotten into publishing a lot sooner and perhaps in a more traditional fashion.

A decade later, as a teenager who ran off to Southern California, I immediately got into self-publishing. It was 1987, and I wanted to write about everything I was experiencing as an audio engineer, so I started a fanzine. In retrospect, mine was terrible! It was hand-written, the photos had no half-tone screen, and everything was taped to the masters. There were just a few copies made of those early, very poorly produced issues. With each subsequent edition, however, I improved the quality in every way I could. By 1992, I was printing 10,000 copies per issue, had four issues per year, had it printed on a web press, had a glossy, full-color cover, and had international distribution.

By 1996, I was contributing and hiring out my writing, photography, production, and editing services to other magazines as well as record labels and authors: Flipside Magazine, Ben Is Dead, Maximum Rocknroll, Discover Hollywood! Magazine, Working World Magazine, Unreinforced Masonry Press, Priority Records, Transparency, Delicious Vinyl, Capitol Records, EMI Records/Music Publishing, etc. I learned how to bang out columns, reviews, and articles as fast as I could type, and I was ever-ready with a camera. I also found myself as a mentor, something which I should have been more mindful when doing so back then. I had knowledge to impart but a terrible bedside manner when imparting it. Nevertheless, I’m happy that many of those folks — such as Maggie St. Thomas, Teka Lark-Lo, and Kelly DeSaint — have gone on to publishing careers.

In 2002, I ended everything and went to NYC. I started up a micro-press, Metropolis Hopper Books. I was quickly bored, and I sought a new avenue of publishing: newspapers. I got a crash-course in newspaper editing and writing by Michael Bradley (a protegé of Ben Bradlee — the Washington Post editor who back in the day gave the green light for the Pentagon Papers to be published) while employed by a group of Brooklyn tabs under the Home Reporter umbrella. That lasted a few years, and I returned to L.A. in 2006.

In L.A. I needed even more stimulation. Within a few months, I had a partner: a fellow poet/writer/artist. We started up a poetry broadsheet, “BrickBat Revue,” as well as a daily blog (replete with photography and investigative journalism) called The Bus Bench. Soon thereafter, we started a far more serious endeavor: a community newspaper. The Morningside Park Chronicle lasted until 2015 when the corruption it was uncovering prompted so much potential violence (via home break-ins and outright threats from politicians) that it and our partnership was dissolved.

I took a break for a few years and did shitjobs. In 2020, I resurrected MetroHop Books, and in 2024 I published the first volume of “F==K YOUR FLAG: The New Wave of American Political Violence.” The idea for that book (and to resurrect my former NYC micro-press) occurred when I first saw a few desecrated American flags defiled with the face of Donald Trump and the Confederate flag. I started looking for stories, articles, and books on these flags. Aside from related articles by a journalist named Jeff Sharlet, there were none. Then there was an insurrection to overthrow the American republic. The mass wave of desecrated, seditionist flags seen that day prompted loads of magazine and newspaper articles — but no book to explain the emblems. Toni Morrison once stated, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” No one had written such a book, so I set about doing exactly that.

What’s a lesson you had to unlearn and what’s the backstory?

I had to unlearn what I thought I knew simply because what I had learned looked the same on different paper.

I’m still learning the lesson of listening, especially when somewhere different. As a youth, no one listened to me, and I spent my time reading, writing, drawing, and observing. When as a teenager I realized I had a mouthpiece — my second fanzine — I went berserk. I thought I knew all the answers simply because people responded to my rag, wrote me letters out of nowhere, quoted me on stage, in newspapers, and in other zines. When I read back through all the stuff I published, especially the interviews, I realized I was talking over folks, trying to redefine what they were saying, and was generally deaf to them. I was young, I was definitely a bit ignorant, and I wish I would have had a mentor to help me understand things a bit better. It took a decade or so before I realized that I was just like anyone else, just louder.

While there’s plenty to learning things the hard way, there are plenty of things that need not be such a waste of time too. Reinventing the wheel steals time from learning how to drive, right?

I’m still learning that lesson, and I’m trying to learn it as well as possible.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

I feel there are a few conflicts that can organically sprout between logical folks and creatives. The perception of time is one. Artists tend to need large blocks of uninterrupted, consecutive time to create. The exponential effect of artistic development can’t be broken down in two hours here, 30 minutes there. To stop working on a project is to halt the developmental momentum, and it can prevent the original idea from fully blossoming. It’s not like a shitjob where one clocks in, works until the first break, and then starts again afterward at the same point. To stop writing, painting, filming, etc., is to prevent what could be from being. It kills the energy, and it’s why creatives tend to work until physical and mental exhaustion drops them. Time away from a work, even in mere seconds, can seem like hours. To a logical person, that seemingly brief bit of time can seem like nothing. To a creative, those few seconds required to find a piece of paper or a pen on which to jot a thought, the idea or the color of it can dissipate — and those milliseconds of floundering can diminish a possibly monumental idea.

There’s also the literal and the figurative perspectives. My partner is maddeningly literal; my behavior is dada. She sometimes finds my sardonic comments frustrating even as what is often simply silly (to me, at least, and would be to my friends who’re writers and artists) is taken as insulting by her. She is an excellent listener, however, and while she often gives me a chance afterward to not be obnoxious, to explain myself (which I find frustrating, because I feel like a comedian having to explain a joke — and that does nothing to help the situation!), she’s still human. I’ve learned how to respect her demands that I explain that which I assume she’ll understand. It has helped me to understand how I should be a lot less flippant. Although she’s a doctor (a proper doctor, I might add, and not a medical one) as well as a former singer (I won’t name the ensemble), she’s as much a non-creative as I am non-mathematic and non-scientific. I don’t mean to be harsh when I simply state that non-creatives can understand creatives if we creatives listen to how and what they are asking and seriously answer them — so long as we are not expected to stop creating for the moment!

Contact Info:

- Website: https://metrohopbooks.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/metrohop/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/MetroHopBooks

- Twitter: https://x.com/BreweryObserver

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@MetroHopBooks

- TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@metrohop

Image Credits

all photos ©2025 Randall Fleming/MetroHopBooksLLC