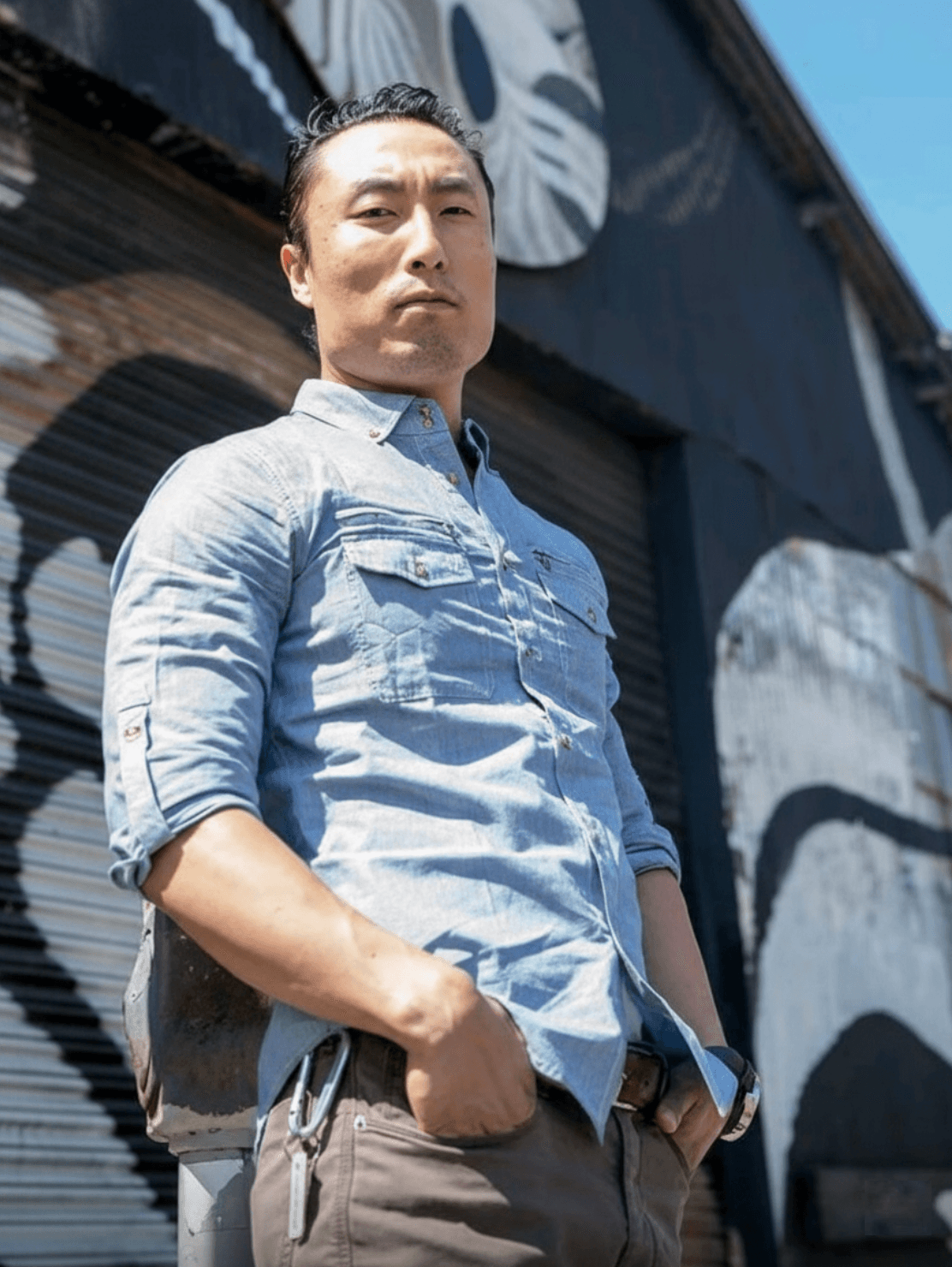

Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Pyung Kim. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Pyung, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you tell us about a time that your work has been misunderstood? Why do you think it happened and did any interesting insights emerge from the experience?

I spent much of my career moving along two paths at once, with a sense that I’d eventually have to pick a lane. When I worked as a screenwriter, I’d downplay the business and systems side of me. In business contexts or consulting jobs, I wouldn’t mention my screenwriting experience, as if being an artist made me less serious. The world seemed built around clean labels, but no single label gives the full picture. Depending on who I was talking to, it felt like I was always cutting off a part of who I actually am, and that can be frustrating.

If there was any throughline, I didn’t fully understand it myself yet, so to me these would remain two separate, parallel tracks.

It wasn’t until much later that I saw the connection. Both writing and business are fundamentally about making decisions under constraint. There’s a way to look at a screenplay, the art of it, as a dense sequence of macro and micro decisions: what question is this scene answering (or refusing to), what pressure am I applying, what choice can’t the character avoid? Business isn’t that different. Strip away the jargon and it’s a series of decisions about tradeoffs, incentives, timing, and risk.

And in both cases, the real treasure isn’t in the answer. It’s the framing. My good friend and mentor Joe once told me that a mediocre answer to the right question beats a brilliant answer to the wrong one. AI is now making this truth unavoidable. In a world where execution becomes cheap and abundant, the real value shifts to knowing which questions are even worth asking at all.

Looking back, being “misunderstood” wasn’t personal – it was structural. Few systems were built to recognize judgment, framing, and taste as marketable skills. But pretty soon, that’s all that’s going to be left.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

I grew up in Virginia in a Korean American family, and early on I learned how to read rooms and move between perspectives. Living in that in-between shaped how I think and work far more than any formal training. I started out in media by working in production at Warner Bros., which revealed the practical realities of storytelling, which turns out is about far more than just inspiration (it’s also about choices made under pressure). Writing was always the goal, and I went on to be hired to write feature films and shorter projects across a range of genres, including rom-com, family, thriller, and animation, as well as other formats like comics, games, and narrative podcasts.

On the business side, I was fortunate to learn under a multi-faceted businessman fluent in both creativity and commerce. Working at his consultancy taught me how organizations actually make decisions. That path led me to work with brands like Amazon, Red Bull, and Squishmallows, often in roles that sit between technology, emerging workflows, and new business models.

Today, my work spans all of these areas. I write and develop creative projects, and I also work in business and innovation strategy, helping organizations decide what’s worth building (and what isn’t). No matter what the project, I’m drawn to the same challenge: bringing clarity to moments where the stakes are real and the answers aren’t obvious.

Are there any resources you wish you knew about earlier in your creative journey?

I wish I’d understood even earlier how valuable mentorship can be, especially when it comes from outside whatever lane you think you should be in. Creatives are naturally open, but we may not always extend that openness to people who work outside our particular industry. If you’re a young writer, some of the best teachers might come from other spaces, not just in or around the writers room. In my experience, creativity sharpens when you stay open to insight wherever it appears.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

I did well in school and grew up believing that being “smart” meant mastering material and having the right answer – until work confronted me with problems that couldn’t be solved by domain knowledge alone. Writing was what exposed that gap first. On the page, the harder I chased the answer, the more it ran away.

That’s why an idea from the comedy writer (and creativity researcher) John Cleese clicked: most schooling trains us to live in closed mode – rush, pressure, premature certainty. But the hardest problems actually require open mode: play, patience, and a willingness to be wrong. It’s less about chasing the solution and more about letting it come to you. I’d hear the same insight from great creatives everywhere. Rick Rubin lies down in the studio when he produces hit songs. Jerry Seinfeld says his best jokes don’t feel like they come from him at all and that he’s just a conduit.

Turns out these principles apply not just to art, but to the hardest problems in business, technology, and strategy too – especially now, when ChatGPT already “knows” more than any individual ever could. The real work isn’t about forcing outcomes; it’s setting conditions. So I had to unlearn this idea that creativity is rare, or purely intellectual. It’s actually a way of operating. One that often requires unlearning all that keeps us closed to what’s already available to all of us – if we just make the space.

Contact Info:

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/pyung-kim/

Image Credits

Andrew Snavely

Lorenzo Belmonte