We recently connected with Peter Littlefield and have shared our conversation below.

Peter, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you talk to us about how you learned to do what you do?

I wanted to work in the theater, so I moved to NYC in 1974. Rent was cheap, and if you were willing to work for little or no money, you could work with some of the great theater artists of the time. The New York theater world was divided between Broadway/off-broadway and Downtown. I inclined downtown. I didn’t really like naturalistic theater – which seemed forced to me – and I began learning from people who approached theater like a painter approaches a canvas, theater that puts emphasis less on the verbal and more on the conceptual and visual. I worked for a number of directors – Joesph Chaikin, Maria Irene Fornes, Lawrence Kornfeld – who had a way of creating a language of stage images that ran against the dialogue.

The speed with which I learned had to do with my own character, which tends to move slow when I’m learning and then suddenly ‘gets’ it. I worked as an assistant director in theater and opera for about 5 years before I got a chance to direct anything. I hadn’t even directed a scene in college when I got a gig directing Verdi’s “Rigolleto” at a small opera company in California, Hidden Valley Opera, not an easy opera to start with. One day, I looked up at the staging of a scene I’d done, and I thought, “Oh, I can do this!” It was kind of a surprise, but somehow I drew on a visual sense I didn’t know I had. I learned mainly by observing the creative process of theater artists I worked for, their particular way of getting hold of something. I didn’t imitate them. I found something I grasped in them – in myself. I learned through apprenticeship, which to my mind, is a better method for learning to be an artist than graduate studies. You work with artists there too, but when you’re an apprentice, you’re out in the real world of making theater. Grad school tends towards an institutional ethos that brings with it a peculiar kind of theater group-think. I was in the drama club in college, but I learned most about making theater from studying English literature. By reading and writing about literature, I learned how to find the heart of a work of art. I applied that process to conceiving, writing, designing and staging a production.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I moved to New York City in 1974 to find work in the theater. I got a job as an assistant stage manager on a production of “The Seagull” directed by Joseph Chaikin – a visionary theater artist – and that opened the door to the downtown avant-garde theater world, and particularly to a long-time association the Cuban-American playwright/director, Maria Irene Fornes. I worked on many productions for Irene, and she became my teacher. While assisting other theater artists and observing their creative process, I developed one of my own that I began to apply to theater work. I helped start a club in the East Village called The Pyramid Lounge, where I wrote and directed many original performance works. Also at The Kitchen and other downtown spots.

At the same time, I worked in opera, beginning with the Santa Fe Opera and moving to major companies in the United States and Europe. As opera developed an avant-garde niche, I specialized as a kind of creative collaborator or dramaturg, deconstructing an opera’s cultural assumptions and finding ways to strike more directly at its dramatic heart. I have especially had a very long, 40 year collaboration with the opera director Christopher Alden, with whom I won the Olivier Award, co-directing Handel’s Partenope at the English National Opera. I recently adapted James M Barrie’s Peter Pan with Alden at Bard’s Fisher Arts Center.

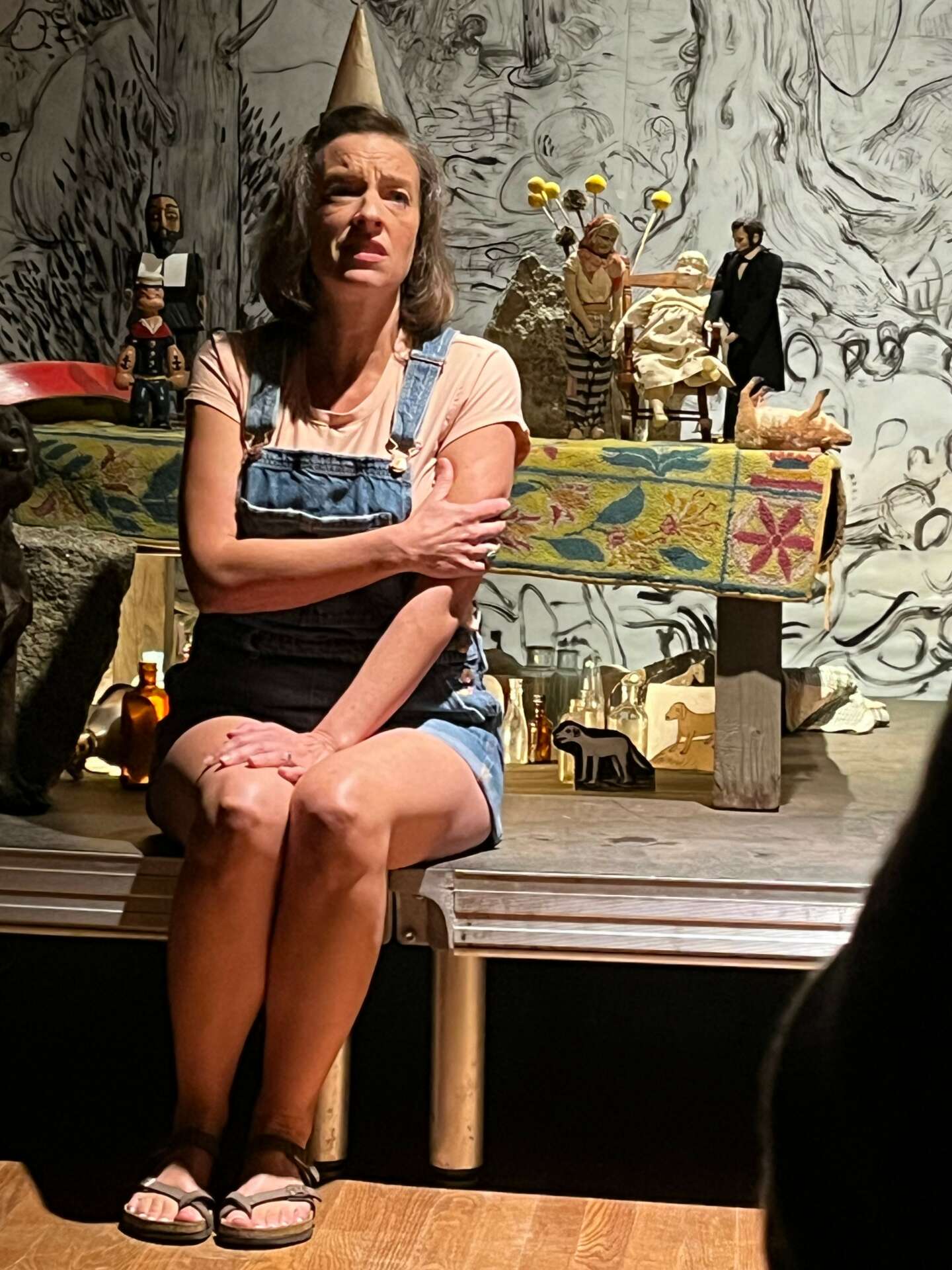

I divide my time between opera and original theater and film work, as a director and writer. For 20 years, I have collaborated with the director, Roy Rallo, on opera productions and original work, including a series of films from my screenplays, under the title, What she learned former plants. I have written a new film, now in preparation, called God’s Mom, based on Revelations. Lately, I have been creating original theater work for and about the city of Gloucester, Massachusetts, which has a very dynamic and unusual artistic environment. In 2023, I staged my adaptation of an old poem that takes place in Gloucester, Dogtown Common for the year-long Gloucester 400+ anniversary celebration. I am currently working with the artist, Gabrielle Barzaghi on an installation called The Resurrection of Judy Rhines, also based on Gloucester lore. I teach playwriting at the Cambridge Center for Adult Education and the Gloucester Writers Center.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

I’d say I’m more determined than resilient. I grew up in old Yankee culture that seems to have gone the way of the dinosaurs. Social values trumped individual impulses, something that doesn’t look so terrible now, given how hard it’s become for our society to figure out what matters. But early on, I realized that if I wanted to be an artist, I was going to have to break out of my Yankee past. So I dropped myself into the middle of the New York downtown, hoping it would challenge me to unbury myself. It was a paradoxical experience. On the one hand, I found that I had creative powers I didn’t know I had. I had a feeling for how to craft a dramatic world out of my imagination, drawing on a bricolage of influences – old American, postmodern, spiritual, the director’s theater, conceptual, etc. I was kind of amazed at how easily I was able to pull a show out of myself. What I couldn’t do was sell myself. I was pretty hobbled by my background, and the strain of staying above water in the roiling New York City waters eventually did me in. After about 20 years, I crawled back to Boston.

Even after I fell apart and had to leave the New York world that meant everything to me, I tried to work out how – given a broken psyche – I could continue to draw from the creative insight that I developed there. I drew picture books. I wrote plays. I wrote down my dreams. I sat on the board of an early music group called The Boston Camerata. All while working in the bookstore of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Then Christopher Alden, an opera director I knew from New York, asked me if I would collaborate with him on a production of the Gertrude Stein/Virgil Thomson opera, The Mother of Us All, at the Glimmerglass Opera. I really wasn’t well. I slept every minute I wasn’t in rehearsal. I would run off during lunch and take a nap. But the production was successful. We did it two more times, at New York City Opera and the San Francisco Opera. And it began a partnership that has lasted to the present. We’ve deconstructed operas all over the United States and Europe, winning the Olivier Award for Handel’s “Partenope” and a nomination for Janaeck’s “Makropolis Case,” both for the English National Opera.

I learned something about my limitations from falling apart and developed a more realistic way of looking for opportunities to to make art. I worked small. I collaborated with people I had a special understanding with and stuck with them. With my friend Roy Rallo, I made everything from major opera productions to experimental performance pieces to a trilogy of films called What she learned from plants. I discovered that my own home town – Gloucester, Massachusetts – is, in creative ferment and generosity, only second to downtown New York. I’ve found an amazing variety of friends and collaborators there, with whom I’ve made performance works, installations, done talks, taught a playwriting class and had many conversations over coffee.

I’d say my challenge has always been to discover the deepest factor at the heart of artistic work and where – in a mixed world – given my strengths and weaknesses – I can bring it out. In that sense, my weaknesses have been as illuminating as my strengths, because, in many ways, they brought me closer to what existence actually is.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

Artistic talent seems to compensate in some way for a person’s other limitations. I’m dyslexic, and, when I was young, ADHD. I would pursue what interested me feverishly, but I couldn’t study. I couldn’t believe that anybody would be expected to sit by themselves for three hours to learn something that didn’t matter to them. I would get so lonely!

But then, in my teens, in the midst of a crisis over my viability as a student, I had a kind of epiphany of the creative power that seemed to well up in my body like a spring. I likened it to a cold, clear spring breaking into a muddy pond. It was a spiritual insight, really – the inner light – that seemed to contain the truth of existence. It threw light on how muddled my thinking was, and it showed me how to bring it closer to its order. And it didn’t fade. I kept coming back to it. I couldn’t believe it was still there. It lasted for the rest of the year, and I did whatever I needed to do to align my mind with it. Because it answered a question that dogged me: does the tangle of compulsive yearning in us add up to anything?

I realized I had to treat my mind like it wasn’t very bright. When I read a book, I underlined practically every line in it, and I took notes. I got a fountain pen. I studied! And then it turned out that I was smart. I didn’t realize it, but I was taming my mind the way a cowboy tames a horse.

That insight became a compass, a truth against which I measured life’s variability. Is it Chi? The Creative Spirit? The Paraclete? I don’t know, but I’d say that my artistic quest has always been spiritual. It has driven me through many ups and downs, pushed me out onto limbs that broke and showed me the way out of the hole I fell into. It gave me a practice, and feeling for the materials out of which I craft my art – conceptual, dramatic and visual – that I try to draw on in a deepening relationship with existence.

To answer another one of your questions – about what you might tell a “non-creative” – if there is such a person – to help them understand an artist, I’d say we tend to be driven by a heightened discernment of some kind that it is a matter of life and death for us to crystalize. Which is why we can be very particular about seemingly inconsequential things.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: samuelnomad

- Facebook: Peter Littlefield

- Other: Vimeo – Peter Littlefield. Videos: “What she learned from plants,” “Travelers,” “brother dud” Cambridge Center for Adult Education, teacher: Playwrights Workshop