We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Peter Brinson a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Peter, thanks for joining us today. Can you talk to us about how you learned to do what you do?

I’ve been teaching game design students for over 20 years. I’m able to stay relevant – to sustain my empathy for what my students go through – because I’m always learning. Video games are so hard to make, and I find myself perpetually learning.

This all makes sense when I accept that functional artists are always out of their depth. Ideally, they find themselves just below that threshold, not completely out of their depth, and not well over the line (a bored master of their craft).

The key is to identify how to turn your own limitations into intention – into a style or voice. If you’re waiting to master the tools before you can express yourself, then you’ve got it all backwards.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

After studying experimental film in college a couple of decades ago, I recognized that I was a bit late to that endeavor. There, pursuing “the new” was not new.

But video games were right there. At that point they had only been commercial products, associated with companies rather than creators. I had grown up with video games no doubt, so I felt oriented learning to code them, and interrogating how they were expressive. I am still doing that.

Along the way, other folks wanted to do the same. It was natural to be part of the emerging academic discipline – game school.

What’s a lesson you had to unlearn and what’s the backstory?

Lately, there’s talk in culture that we should be afraid of A.I. becoming more human. But we have it backwards. We should be concerned about people becoming more like computers.

Computers have been around a while now. We’ve observed what they can do and how they do it. They embody productivity perfectly and completely.

But I’m trying not to follow their example. I catch myself thinking: how can I be more efficient with my day? I have an hour before my appointment; what can I squeeze in? Should I take on a new craft before next week?

Here, computing stands as an unhelpful influence. For all of time, successful artists (as well as scientists) have spent parts of every day doing nothing in particular. Daydreaming? Yes. Reading anything at all? Sure. Brainstorming with others? Ideally, with no goal in mind, thank you.

Alright – so here’s a fun one. What do you think about NFTs?

Since I’ve never been good at predicting the next trend or any permanent shift in culture, the best I can do is to be skeptical and not cynical.

With NFT’s, it is valuable to look coldly at what they can do versus what they express. (Artists know all about expression versus utility). NFT’s express the ideals of individuals breaking from institutional control. Is that what NFT’s actually do? I’m guessing the answer is: sometimes.

Banks and art galleries have reputations that they perpetually maintain. If my bank card fails a few time in one week, I will consider that entire corporation a failure. I don’t want my card to fail, but neither does my bank. Wow, we want the same thing?

Reputation is a kind of technology, a way to assess if an institution or group can give me something I want.

For, say, contracts, NFT’s can replace lawyers. I have an instinct to see lawyers as people who can control my livelihood through their power. But my rational-minded perspective recognizes that this is my emotions at work. And so, it is vital that I look at any promise of computation replacing people for how that change will actually impact the circumstances independent of some else’s advantage. Does my sense of fairness hamper my experience of freedom?

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.peterbrinson.com

Image Credits

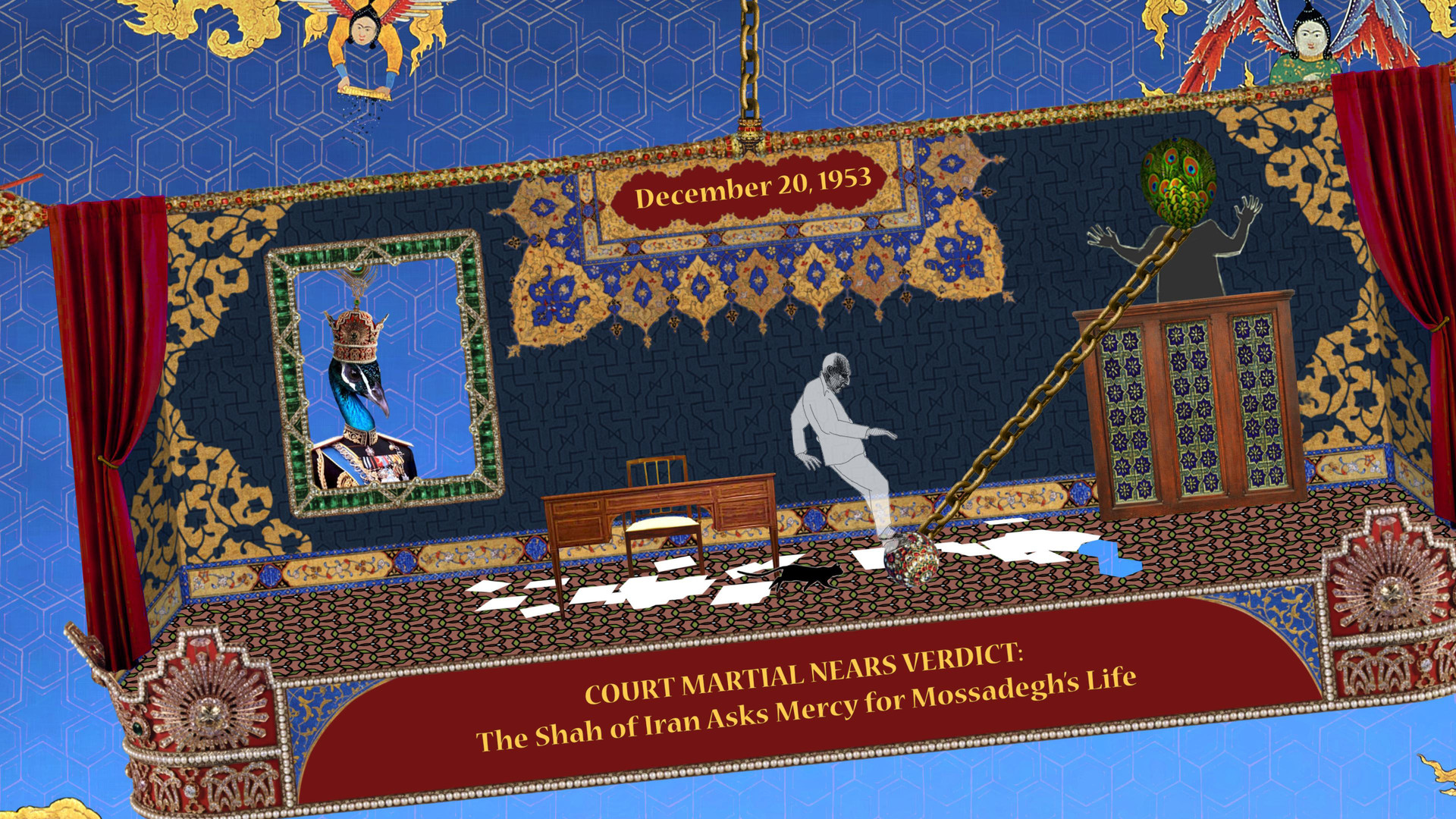

for the CATC.jpg, credit Kurosh ValaNejad.