We recently connected with Pamela Lowell and have shared our conversation below.

Pamela, appreciate you joining us today. We’d love to hear the backstory behind a risk you’ve taken – whether big or small, walk us through what it was like and how it ultimately turned out.

During the late summer of 2022, having just moved to a new area on the south coast of Massachusetts (in search of community after Covid) my husband and I went kayaking one afternoon on the Westport River. Unbeknownst to us, this river holds one of the densest populations of Osprey on the entire East Coast. I’ve always been a nature enthusiast (as a balm for my work as a psychotherapist specializing in treating trauma) but that August, I sat on my kayak in awe. We happened upon this area during fledging season, when that year’s population begins to learn how to fly, and there were dozens upon dozens of Osprey circling overhead. There are about one-hundred nests spread out on the salt marshes of the Westport River. That night I fell asleep dreaming of painting large watercolors of Osprey in sepia tones—and maybe donating them to nature organizations. For a while, I’d envisioned doing some volunteer work in my retirement for nature organizations; that seemed like a noble path. Yet could I just start painting again? I’d majored in art as an undergraduate, but what made me think I could resurrect a talent I’d let go dormant for decades? A talent I’d never had much confidence in to begin with? However something kept pulling me forward. Although I’d never sold any of my work, or exhibited in any gallery—ever—or even picked up a paintbrush in years, I dusted off my easel and began.

Coincidentally, just a few weeks later, a friend told me about a local nature organization which was having a fundraiser that January, and would I want to donate one of my paintings? I barely felt qualified. Would they accept it? I asked. She reassured me they would. So I painted an Osprey, landing on a platform, with the grasses of the salt marsh in the foreground. It was a silent online auction, and many of the talented artists in the area had also donated their work. I was excited to have my work in a gallery for the very first time, but for a long agonizing week my painting didn’t get any bids at all! I was so embarrassed, and discouraged, and couldn’t wait for the show to be over so I could put that painting in a closet where it apparently belonged. But then on the closing night of the exhibit, something incredible happened: there was a bidding war. On my painting! That painting of an Osprey ultimately netted the highest bid in the show: hundreds and hundreds of dollars for the Westport River Watershed Alliance. And it made me wonder, perhaps this was a dream worth pursuing after all.

But that wasn’t the end of it. That spring, the Cape Cod Museum of Art put out an international juried call for art, for its IN TANDEM exhibit. Artists were to address the theme of two or more things working together for a desired result. I submitted another Osprey painting, this time with a platform built by humans, symbolic of helping the Osprey’s recovery from the threat of extinction so many years ago. Still, what were the chances my work would be selected for the exhibit? There were hundreds of entries from eight different countries! When I received word my painting had been chosen, I was thrilled. I also realized that I now had a different kind of platform, the opportunity to use my art not only to help nature organizations, but to educate and inspire others to take action to protect and preserve the environment. At the opening reception, when each artist had the opportunity to address their process, I used my time to discuss the importance of limiting nitrogen and preserving our salt marshes, so that the Osprey, who were once on the brink of extinction, could survive and thrive for the next generation.

Ultimately, I took a risk, picked up a paintbrush, pushed through my fears and insecurities, and put a vulnerable part of me out there into the world. This risk, however, led to other risks, and moved my art and ultimately my mission forward to the next logical step of translating those images and capturing those experiences into a book, something I swore I’d never do again, and hadn’t in almost twenty years.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

I’ve been a licensed clinical social worker for almost four decades, and treat people with complex trauma in my private practice with a variety of modalities including EMDR and IFS. I have also served as a consultant, clinical director and trainer of trauma informed care for not for profit agencies in and around Providence, Rhode Island. But I’ve also been a nature enthusiast and creative person for my entire life.

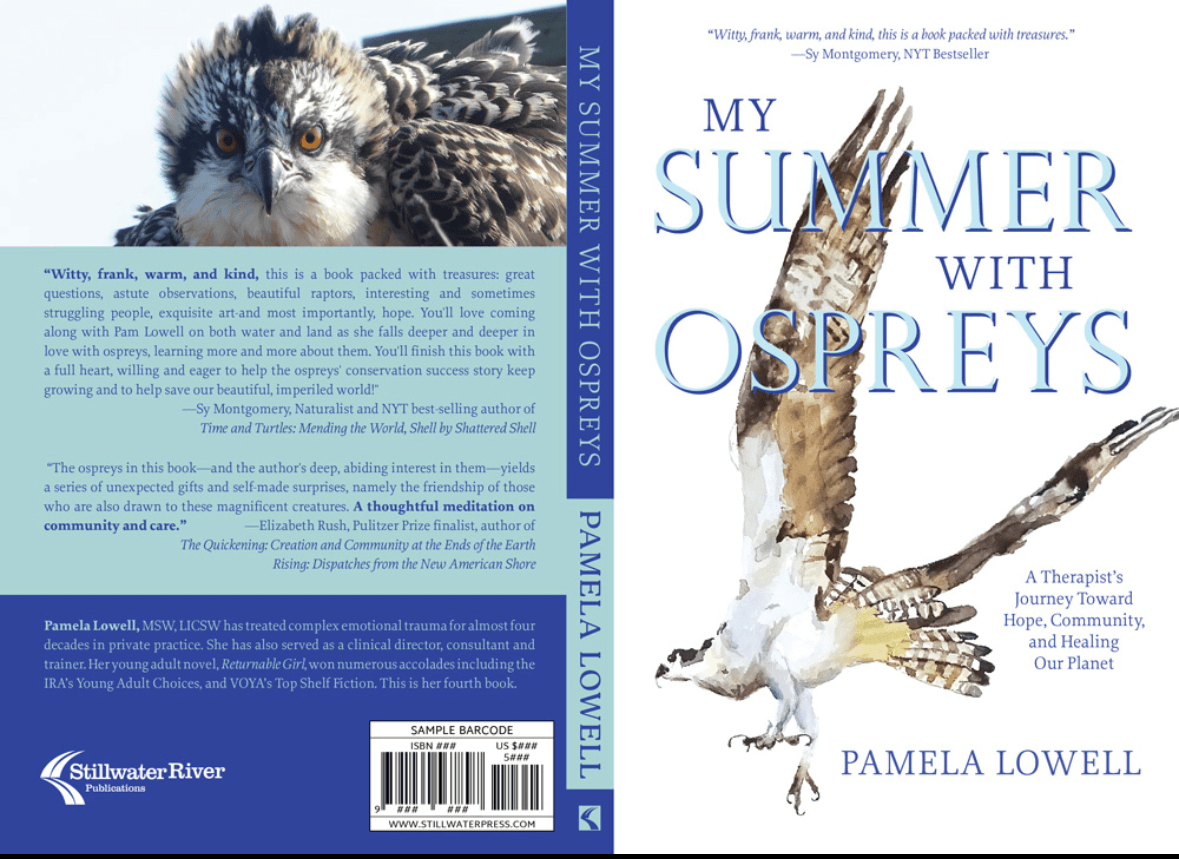

Indeed, it’s my art, large watercolors of Osprey and their habitat, and my most recent book, “My Summer with Ospreys: a therapist’s journey toward hope, community and healing our planet,” that give me the most joy. The book is illustrated with my original water color paintings and Sy Montgomery, NYT best-selling naturalist, describes it as a book “packed with treasures.” The book outlines my journey as a volunteer one summer with Massachusetts Audubon, working with their Osprey translocation project, but it ends with a call for action to help save our planet. A percentage of the profits from my creative works are donated to local nature organizations. In addition, and maybe more importantly, I have presented my multi-media program at various venues in multiple states including birding groups, nature conservancies, Audubon chapters and psychological/climate conferences including most recently the Creativity and Madness Conference in Santa Fe.

What sets me apart from others in these spaces is the trauma lens I bring to both my writing and my art. I use this knowledge to help bring more awareness to the fragility of our natural world and have developed a model for communication around these sensitive and often complex topics. Once I began to envision our planet, Mother Earth, as a trauma patient showing up in my therapy office, I realized I could I re-create that scenario for audience participants who attend my presentations, encouraging empathy a new way of seeing the world, and a call to action. But not only that, my model encourages connection, community, accountability, agency, and role modeling—things that psychologist Albert Bandura says are integral to change in the climate crisis space. With my art and work I want to inspire people to make a difference in their part of the world, to take a risk, to move from fear and despair towards connection and hope and, ultimately, towards healing our planet.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

The most rewarding aspect of being an artist is connecting with people. Whether it’s someone who is interested in purchasing one of my paintings or prints, or someone who has recently discovered my book through a recent podcast appearance, such as Birding for Joy, The Hopeful Environmentalist, The Thing with Feathers, or the Mindful Birder—I just really enjoy connecting with people and hearing their stories. Now, obviously, as a therapist, I’ve been listening to stories for many years, but in that role I’ve always listened with an ear towards healing their trauma. Now I get to connect with folks around our shared love of birds or art or nature (much more fun) and hopefully, eventually, to connect around healing our planet. It’s extremely gratifying to hear how people relate to my story, and all the various ways they connect to the things I’ve had to overcome personally on my journey. The reception for my art and book has been wonderful, and to have all of it be so warmly and enthusiastically received, well, it has been one of the greatest joys of my lifetime.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

I think moving from a generalist to a specialist is a lesson that young people should be taught in school before they launch into their careers. I’m now very specific in the clientele I treat in my practice, (trauma) to what I paint (Osprey) to what I write and speak about in my talks (helping the environment). I now trust that the specific is universal, that you can’t be all things to all people, but that once you find your people (or they find you) that there is nothing you can’t accomplish, and that people will long remember you for what you’re specifically interested in, knowledgeable about, and inspired by—it’s human nature!

There’s no real backstory in this for me, except that at every turn, I have sometimes doubted that this was the approach which would bring about the most success and personal satisfaction and joy, but it’s never failed to do so. Every single time.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.pamelalowell.com

- Instagram: @palwrites

- Facebook: Pamela Lischko Lowell

- Twitter: @pammystweet

Image Credits

Casey Addason (podium shot)