We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Noe Kuremoto. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Noe below.

Noe, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you talk to us about a project that’s meant a lot to you?

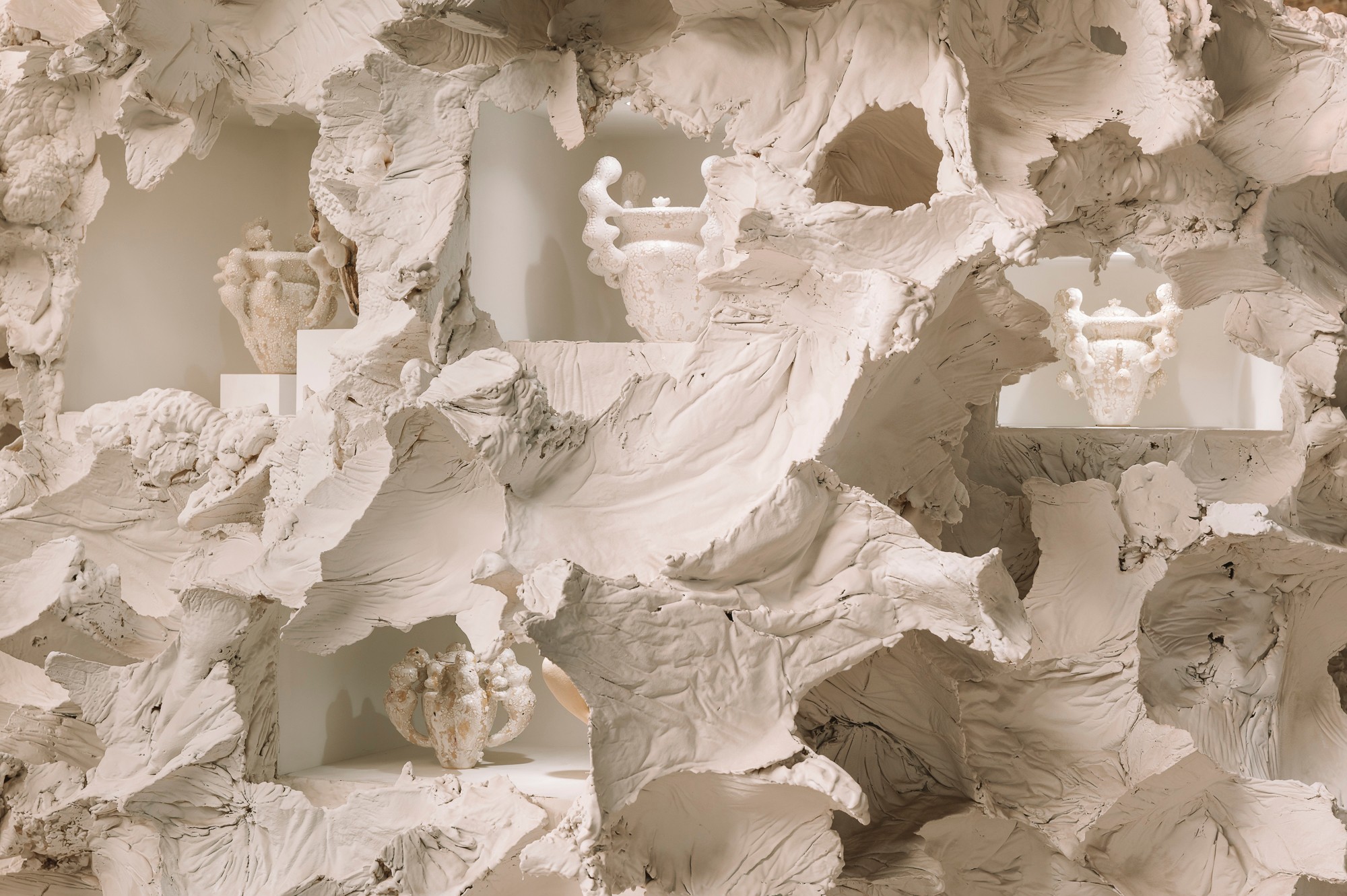

PROJECT DOGU LADIES

A talisman for the history she makes.

Interviewer: So, Noe — Dogu Ladies. What’s the story behind them?

Noe:

It really started with me thinking about how we talk about women, ambition, and motherhood.

For women like us — who’ve built careers, studied hard, travelled — motherhood almost feels like a plot twist. In our twenties, having a baby is seen as a setback. You’re supposed to be building your career, not a family. You tell yourself, I’m not a baby person, or I’ll do that later.

Then later arrives — and suddenly you’re balancing a newborn, a partner, a job, your identity — and wondering how the hell you’re meant to keep it all together.

I had my first child in my late thirties, then my second, third, and fourth in my forties. And honestly? It’s wild. Maintaining a career, a relationship, and raising children at the same time — it sometimes feels almost mythical.

That’s where the Dogu Ladies come in. They’re my salute to the career mother — her strength, her resilience, her refusal to quit.

There’s no real historical roadmap for this version of womanhood. We’re writing it as we live it.

So these vases — they’re like talismans for that. Symbols for the history we’re making ourselves.

Interviewer: And Dogu? That’s from Japan, right?

Noe:

Yeah. The word comes from these ancient Japanese female figurines — from, like, 14,000 years ago. They’ve got these big eyes, wide hips, large breasts — all symbols of fertility, of safe delivery, of life continuing.

I love that idea — that even thousands of years ago, women were making objects that carried hope and strength.

The Dogu Ladies are my modern version of that.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

Interviewer: Noe, your work feels ancient and futuristic at the same time. Where does that come from?

Noe:

I think I’m always standing somewhere between the old world and the new one. I sculpt everything by hand — no machines, no shortcuts — just me, clay, and time. It’s kind of a ritual. I don’t plan much. I let the clay tell me what it wants to become.

A lot of my pieces come from Japan’s old spirit figures — the Haniwa, the Dogū, the Komainu. They were guardians, protectors against invisible forces. I love that question: what are the invisible forces we need protection from today?

Interviewer: What do you think they are?

Noe:

Disconnection. Speed. The pressure to always be logical, efficient, productive. We’ve built a world that’s smart — but not wise. My work is like a slow rebellion against that. Each piece is a way of remembering something instinctual, something ancient we’ve forgotten but still ache for.

Interviewer: You grew up in Osaka and moved to London pretty young, right?

Noe:

Yeah, I came to London in the ’90s to study conceptual art at Central Saint Martins.

Back then, it felt like freedom — no bowing, no rituals, no ghosts. Just forward, forward, forward. Science had all the answers, right?

But after a while, I realised facts aren’t wisdom. And wisdom is what keeps you standing when life cracks open.

Interviewer: And life did crack open.

Noe:

Oh yes. Love, marriage, motherhood, loss, illness, war, the economy collapsing — the full human syllabus. (laughs)

And through all of it, I found myself returning to the myths I’d once tried to escape. Those spirits never really left; they just changed shape.

Interviewer: So mythology isn’t nostalgia for you — it’s something alive?

Noe:

Exactly. Myth is a living language. It’s not about superstition or blind belief. It’s about wisdom that moves — that adapts. I don’t want to bury the past; I want to keep it breathing.

Because if we don’t carry the wisdom of the past, we don’t become free. We just become lost.

Interviewer: That’s powerful. So what do your sculptures mean to you, personally?

Noe:

They’re not just objects. They’re vessels of meaning. Each one holds a piece of survival wisdom — something I’ve had to remember the hard way.

And honestly, my biggest hope is that my sons see the world as a beautiful place because of them. Every sculpture is my way of saying: you can build beauty from the mess.

Interviewer: And now you’re splitting your time between London and Lithuania?

Noe:

Yes, I lived in London for almost 30 years. Our family home is here but we’re also building a studio deep in the Lithuanian forest, near the lakes. It’s my husband’s home land. It feels like returning to something raw and essential. Out there, I can hear myself again. The universe feels closer.

Interviewer: If someone holds one of your pieces, what do you want them to feel?

Noe:

I want them to feel stillness. Maybe a bit of mystery. Maybe like they’ve just remembered something ancient they didn’t know they’d forgotten.

Because that’s what I’m doing, really — trying to give old stories a new heartbeat.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

PROJECT SHODŌ

A conversation about perfection, paralysis, and one tiny step forward.

Interviewer: You mentioned that Shodō became a turning point for you. Can you tell me the story behind this project?

Noe:

Ahhh, that’s a good question. (laughs)

Honestly, Project Shodō came out of me trying to survive motherhood.

There’s this image in my head — the Ideal Artist. The Ideal Mother.

Both beautiful. Both terrifying.

The artist ideal messes with my head.

The mother ideal messes with my heart.

Put them together… it’s chaos.

Interviewer: Chaos sounds about right.

Noe:

Yeah. One of our greatest strengths as humans is that we can imagine our ideal selves.

But that’s also our curse — because we spend our lives judging ourselves against that image.

Some people thrive on that pressure. Me? It just crushes me. I freeze.

When I start a new collection, my mind instantly goes:

No one cares about your art. You’re too slow. You’re too old. You’re not spending enough time with your kids. Just eat some wasabi peas and give up. (laughs)

And part of me believes that voice. That’s the scary thing — it sounds reasonable.

Interviewer: So how did you find a way out of that cycle?

Noe:

I realised I was punishing myself for not being where I thought I “should” be.

I had to flip it.

Instead of punishing myself for not reaching the ideal, I started rewarding myself for moving even a tiny bit closer.

That’s when I went back to Shodō — traditional Japanese calligraphy.

As kids in Japan, we used to write Kanji characters every morning — brush, ink, paper. The smell of Sumi ink is still so vivid to me. We were told that writing our intentions would help make them real.

It’s a spiritual practice — one stroke, one breath, one act of awakening.

Interviewer: And you translated that into clay?

Noe:

Exactly.

After becoming a mother of four, my whole system had to change. My studio time shrank from “all day” to “three sacred hours.”

So instead of trying to make a masterpiece, I treated clay like calligraphy. One stroke a day. One sculpture a day. No edits, no overthinking. Just movement.

At first, I told myself, “Even if it’s ugly, even if it’s bad — just make one.”

Within two days, I had two pieces.

A week later — seven.

A month later — thirty.

Then a hundred small sculptures staring back at me, proof that something was shifting.

It wasn’t about perfection anymore. It was about progress.

Interviewer: That’s such a powerful mindset shift.

Noe:

Yeah, it changed everything.

I realised that staying at zero isn’t actually staying at zero — it’s going backwards. Every day we don’t move, we slip into the minus.

So I made a deal with myself: just start. The first dot, the first stroke, the first move — that’s the moment where we decide who we’re going to be.

That beat between can-do and cannot-do — that’s our superpower.

Interviewer: I love that. It’s like creative resistance turned ritual.

Noe:

Exactly.

Project Shodō became my daily act of resistance — one tiny, almost stupidly small step forward every day.

If it helps anyone else do the same — to move even one inch closer to their own ideal — then I’m grateful.

Because that’s all this is really about: showing up, over and over, and letting the answer reveal itself through action.

So yeah… Hello, Ideal.

We’re coming to get you.

Have you ever had to pivot?

This is another great question. I dedicated my entire collection for this matter. I hope my Haniwa collection will resonate with you. I am exhibiting my new Haniwa collection in NY in 2026.

(PROJECT HANIWA

A conversation about fear, calling, and soul survival.)

Interviewer: Noe, your Haniwa series feels really personal — almost like a confession. Where did it come from?

Noe:

Ahh, that’s another great question.

I actually dedicated the whole collection to this exact thing — to the fear of becoming who we’re meant to be.

I hope the Haniwa pieces will resonate, because they come from that raw, terrified place.

I’ll be showing the new collection in New York in 2026, but really, the story started long before that.

For years, I was afraid to become an artist.

Afraid to speak my truth.

Afraid to give up the comfort of a steady job, even though it was slowly killing my soul.

So I stayed agreeable — always smiling, always saying yes — just to avoid confrontation.

And I did that long enough that my own voice went silent.

Somewhere deep inside, it kept whispering: you’re supposed to make art.

But I kept pushing it down, pretending I couldn’t hear it.

Interviewer: That sounds like a very real kind of fear.

Noe:

It was. It’s that quiet, respectable fear — the kind that hides behind good excuses.

I told myself: You have a mortgage, a family. You’re being responsible.

Society loves that story. But meanwhile, my soul was starving.

I became my worst self — the kind of person who can kill their own soul through neglect.

That’s when Haniwa appeared.

It’s funny, because Haniwa in ancient Japan were buried with the dead to protect their spirits in the afterlife.

But my Haniwa?

They’re here to protect our souls while we’re still alive.

Interviewer: So they became a kind of modern-day protection figure?

Noe:

Exactly.

For everyone who feels their job is killing them a little bit each day.

For those who once had a dream, and buried it under practicality and bills.

For people scrolling through social media feeling smaller and smaller inside.

The Haniwa are for anyone who feels trapped between fear and purpose.

They’re a call to stand up. To take that terrifying, necessary step toward your own truth.

To demand the absolute best from yourself — not for glory, but for survival.

Interviewer: That’s powerful — it almost sounds like a rallying cry.

Noe:

Yeah, maybe it is. (laughs softly)

Because I’ve been that person.

The one dying for Friday, the one comparing herself to everyone else, the one smiling to keep the peace.

And I know how easy it is to stay there.

But at some point, you have to choose your soul.

That’s what Project Haniwa is — a kind of love letter to everyone ready to stop selling theirs.

To everyone who’s scared but still wants to try.

We unite.

We stand up.

We make our spirits stronger together.

All my strength to them —

and to you.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.noekuremoto.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/noe_kuremoto_studio/

Image Credits

Photographer Credit: (Each files are named with photographer’s name. Please credit them)

Studio shots : Kestutis Zilionis

Exhibition shots : Clemens Poloczek