Today we’d like to introduce you to Nina Schuyler.

Alright, so thank you so much for sharing your story and insight with our readers. To kick things off, can you tell us a bit about how you got started?

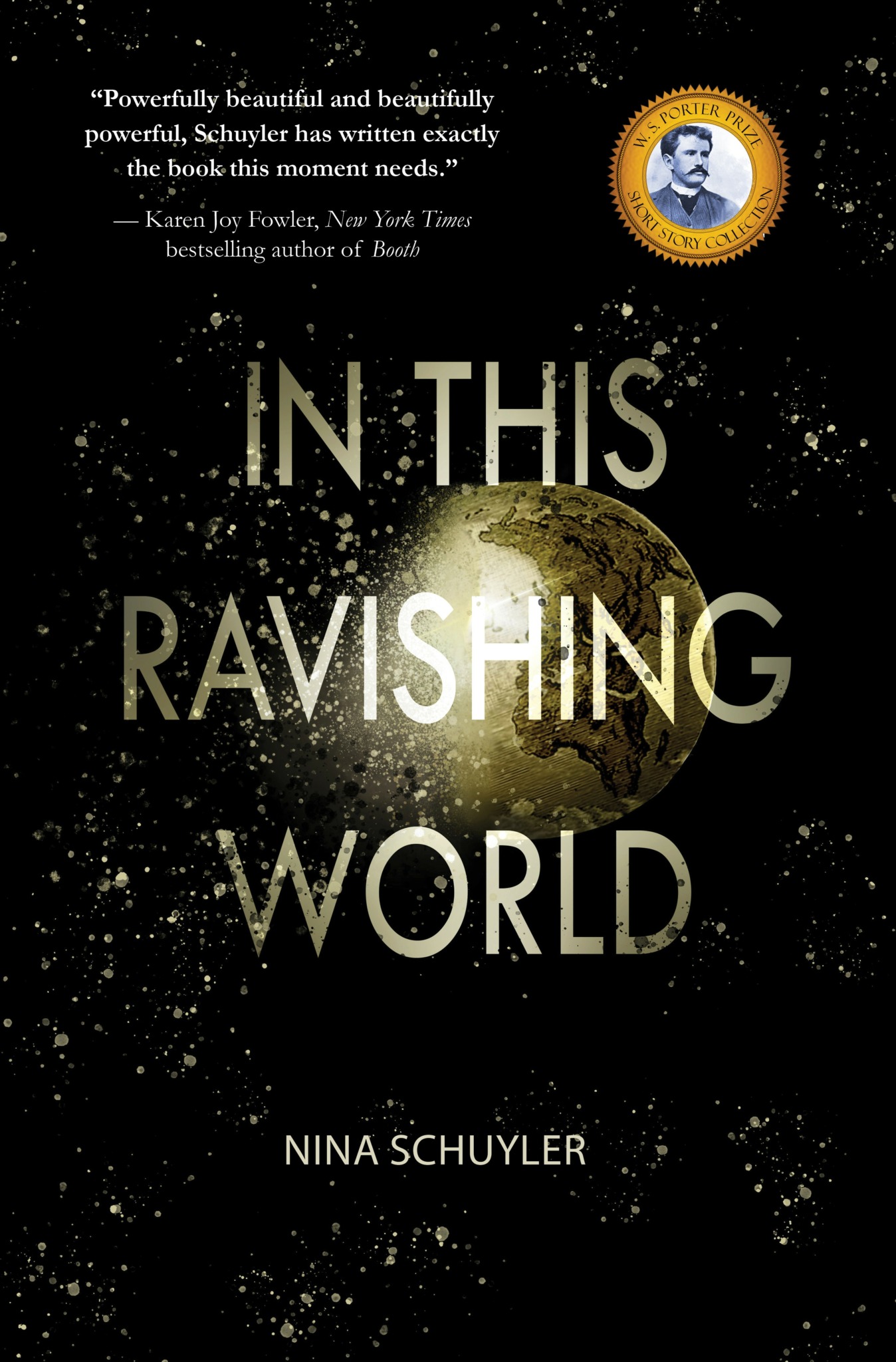

Ten-year-old me loved to read fiction and often did so very late at night with a flashlight. Skip to 24-year-old me, and I was still an avid reader of fiction, but I was also a curious searcher, meaning I became a journalist. Skip to a little bit older me, who earned a law degree and got to cover court cases, trials, and anything legal for a legal newspaper and magazine. I learned tremendous things working at the newspaper: I learned to write fast; I learned the world is full of fascinating stories; I learned to ask people questions, even the most banal, stupid questions, and to listen closely, and this, you must know, is an art which seems to be dying. Quickly, my ear became fine-tuned to the point of picking up so much. I attuned to the nonverbal, the shift in tone, the abrupt switch in the conversation, or the non sequitur. So much picking up that I had loads of extra material, so I began to write short stories. Skip to my thirties, and I earned an MFA in Creative Writing. Skip and skip: I was hired to teach creative writing when my first novel, <i>The Painting</i>, was published. Like a skipping stone, there was another novel, <i>The Translator</i>, two craft books, and another novel, <i>Afterword</i>, and now a short story collection, <i>In This Ravishing World</i>, which won the W.S. Porter Prize and the Prism Prize for Climate Literature.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

The road has been bumpy, and truly, I have yet to meet a writer who has experienced something that may resemble smooth. If you step out of the dominant paradigm, which in this country is to make money and focus on material success, you’ll need courage and community. You’ll also need play and rigor. Before I committed myself fully to the artist’s way of being, doubt crept in. Can I? But what if…? A friend of mine who is a painter and probably 15 years older than me, gave me Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet. This was long ago, but I still have the book. When I open it, I see this underlined:

“You ask whether your verses are good. You ask me. You have asked others before. You send them to magazines. You compare them with other poems, and you are disturbed when certain editors reject your efforts. Now (since you have allowed me to advise you) I beg you to give up all that. You are looking outward, and that above all you should not do now. Nobody can counsel and help you, Nobody. There is only one single way. Go into yourself. Search for the reason that bids you write; find out whether it is spreading out its roots in the deepest places of your heart, acknowledge to yourself whether you would have to die if it were denied you to write. This above all–ask yourself in the stillest hour of your night: must I write?

Yes. Yes, I must.

Thanks – so what else should our readers know about your work and what you’re currently focused on?

If you read the previous question, you know I answered, yes, yes I must write. I write mostly fiction, novels, and short stories. For each work, I try to do something different because I have a restless mind and I’m not interested in repeating what I’ve already deeply explored. Increasingly, I’ve become drawn to the nonhuman world. In my novel Afterword, I created a story in which a female pioneer of artificial intelligence brings back the voice of her beloved husband. I am fascinated and alarmed by what we call artificial intelligence. In my new book, In This Ravishing World, I anthropomorphized Nature, giving it a voice. The common thread through both books is a deep look at the nonhuman and questioning human exceptionalism.

I’ve been writing for years now, and I’m proud of my patience. I didn’t have it in the beginning. I wanted something I’d created out in the world. Now, I want to create something that goes as deep as it can, psychologically, philosophically, and artistically. I take more risks because I have the years of experience to maybe pull it off.

What would you say have been one of the most important lessons you’ve learned?

We are in a constant state of becoming.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.ninaschuyler.com

- Instagram: @ninaschuyler

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nina.schuyler

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/nina-schuyler-144a9b41/

Image Credits

Bryan Hendon