Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Nina Angela Mercer. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Nina Angela , thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you talk to us about a project that’s meant a lot to you?

First off, thinking about the “most meaningful project” intimates that there could be a scale that could accurately weigh meaning of any one project over the course of this life. And that is hard for me to grasp conceptually. My first form of artistic expression was dance. I started taking weekly classes when I was very young. So, my memories of the lessons imparted there are central to my origin story as an artist. One of the lessons that has been most impactful to my core philosophy is that you have to dance full out; you have to leave everything on the floor. There’s no half-stepping in fire-spitting, and ultimately, every full expression needs to come from that same fiery, passionate place. And when I think of living full out, every project has to be the most meaningful while you’re in the process of making it. In my mind, all of the projects are just different intricately woven panels in a magnificent quilt that I will be able to wrap around me one day. And when that time comes, I will know I have squeezed all the juice out this life, and I can finally just rest, and let it all be. Maybe I’ll take to my bed or porch and contemplate colors like Baby Suggs in Toni Morrison’s novel, Beloved. But for now, I am still seeking that perfect note, that expression of soul that renders feeling with an accuracy I dreamed of reaching, and finally did, when it’s done.

Right now, I am many years into a project that is finally closer to being fully realized than ever before. About ten years ago, I chose to leave my teaching job at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn to return to school for a PhD in Theatre and Performance. The journey there was circuitous. I wrote a play called “Gutta Beautiful” many years ago, and that play pushed me to become a producer. When I started writing it, I was confronting the culture of addiction and the weight of its criminality, how that weight breaks whole spirits, families, and friendships. And I wanted to have a conversation with my block about it all because I could see how we were all implicated in each other’s lives. What I could not have predicted was that my choice to purge these intimate and volatile life experiences would carry me from DC to NYC, where I would join in the push-pull of a competitive artistic landscape that often seemed to have little to do with the healing I understood my art to be at its core.

Writing plays is a gift that comes with a challenging process. But live performance is worth it to me. The connection that happens there is like none other. My choreodrama “Gypsy & the Bully Door” gifted me with the opportunity to write songs and create a Gogo dramaturgy that is rooted in and celebrates the culture of the city that raised me in Washington, D.C. during the height of our Chocolate City years. That project took a decade to develop because I had to learn how to do the thing I had in my mind’s eye. The main goal was to present a sophisticated reinterpretation of a confluence of myths that have roots in the African diaspora, make it contemporary, and have Gogo music at its core as a funky way to transmute energy through storytelling. It’s an epic quest with Black folk at its center. A rite of passage into a protest against capitalist alienation, a comedic and intimate political critique. It is also one choreodrama and ritual performance within a constellation of works. Some of the creators of these works are visionary artists I am lucky enough to call collaborators, friends, accountability partners, fam.

Over time, I came to understand that I wanted to contribute to the shape of this evolving archive. It came down on me as a socio-political charge. And I knew I needed the space and time to see that charge to fruition. I decided to leave my teaching job at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn and return to school for the PhD, understanding that such a committed long-term focus would facilitate the deep study I would need to author a monograph that communicates how these performances merge with ritual practices of the Black diaspora to illuminate pathways, and “make something happen.” Over the course of several years, I committed myself to rigorous study of visionary artists – my elders, collaborators, friends, ancestral pioneers. I traveled to Salvador da Bahia to broaden this study transnationally. And I dedicated my dissertation – “Transnational Ritual Poetics of Blackness in Performance” – to this work. I defended in the spring of 2023, and I graduated that same summer. My two adult daughters, mother, and sister were able to witness that with me. I am thankful.

Finally, ten years later, I am preparing to share the fruits of this labor that is as much about community as it is about my personal transformation. And I am so excited to share this project with the artists who so graciously chose to let me into their processes for it, too. I’m nervous and excited, committed and balancing this with all the life that must happen in the midst of its birth. My intention is that it be the kind of monograph that can reach a diverse population of readers because the artists I am centering in the project intend for their work to have meaning and reach far beyond and in spite of the academy. I need it to call and respond in the way that we do.

What’s deep is that I got the news that the press was interested the day my father started actively transitioning from his human body to pure ancestral energy. He was and is a great friend to my mind. And I wanted to write this monograph and put it in his hands. But the process has taken longer than the years he had here with us. He had frontal temporal dementia and aphasia which means he lost his ability to understand and speak language. That was the most harrowing experience for him. He was a writer himself. He was a lawyer professionally and a people’s advocate at his heart, and he enjoyed portraiture as a young man. But in his final years, he was writing his life story while language eluded him with increasingly cruelty. That makes this project even more meaningful to me. I am writing in his lineage and legacy; he can write with me inside that whisper we know as spirit, pushing me onward despite and because of this whirlwind we are living inside.

Nina Angela , before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I started calling myself a multi-disciplinary artist because people kept referencing me as a playwright. But that had a lot to do with timing. I wrote and produced my first play in 2005. I was 30 years old then, the age when people consider your art emergent and definitive at the same time. People want to be able to say what you do in the most easily recognizable way, or they want to know how to market you, or what job or department you belong in. But I have a MFA in Fiction. And I started out in dance as I mentioned before. In fact, my first paying gigs were as a dancer. I often talk about my time dancing with DC’s Showmobile Program which was a Black music and dance revue that traveled around the city on a mobile stage in the summer months. It was a summer youth job. So, maybe I can’t really call that an official gig, but I I definitely claim being a music video dancer for EU’s song “Buckwild” on the Living Large album. Spike Lee directed it. Rosie Perez was the choreographer for the video. I was 15.

But my parents still encouraged me to steer away from the arts. I was expected to go to law school, and I did after I became a mother to my eldest daughter at 22, but it wasn’t my truth. I remember visiting the dean’s office. I think she was teaching Legal Writing. All the students were supposed to come visit her office to talk about our progress. When I walked in and sat down, she asked me, “Why are you here?” And I took that as a broader question and replied, “I don’t know.” In my memory, I don’t know how I got up from that seat. I don’t know how I explained walking out. I am not sure if she affirmed my sense of displacement or what. I just remember sitting in the stairwell in tears, knowing I had to get out of there. And I did. The next fall, I was in the MFA program at American University and pregnant with my second daughter. While my focus was fiction, there was enough space in the program for me to take a playwriting course as well as Location on 16mm film, Basic Visual Media Production, screenwriting, and one poetry workshop. It just so happened that the play would be the thing … To produce it, I co-founded an arts incubator, OAR, Inc. That’s a longer story for another time …

Thankfully, perhaps because of my deep love for ensemble as a dancer, I lean into collaboration. That has meant performing with Urban Bush Women and Angela’s Pulse. It has meant traveling to residencies throughout the country and gaining the experience of a touring artist. It has also meant working as a dramaturg and performing in my video poem, “Invocation,” which toured internationally with the “Visionary Aponte: Art and Black Freedom” exhibition. It has meant penning poems and directing theatre from time to time. I have followed the call of community as a collaborator, and in so doing, I have stretched and come to know and learn from some true powerhouses.

Lehna Huie has honored my work alongside the work of my sisters dequi kioni-sadiki and Chanel Portia in her film “To Move Mountains,” and it is Lehna who has been most impactful in encouraging me to commit even more deeply to the visual art I call devotional gris gris. I am dreaming about sharing this aspect of myself in an installation and intimate performance that has had at least two titles as it simmers in slow burn becoming. Working titles: “I am Not Your Side-Chic: An Exorcism of Patriarchal Proportions,” or “Mirrors, Shadows, This Body, and Tea.”

I always enjoyed making things with my hands. I even loved handwriting in cursive and print as an adolescent. My father was into portraiture. Back in the sixties, he painted portraits of Malcolm X, Bobby Seale, Huey Newton. We still have them. He painted portraits of people in his community, portraits of himself. He sold some of his portraits for extra money when I was a baby. His father made posters, and he painted still life in oil paint. As a child, I grew up seeing his paintings on the wall at the family house on Hamilton Street in Riggs Park. In junior high school, I was granted permission to take calligraphy classes. It was just a small group of us. But when I got to high school, my focus shifted. I still danced and I would always write and read. But the interest in visual art fell to the back a bit. Still, the image remained core to my practice, this aspiration to paint in language what I might have painted quite literally. In my MFA program, I was more fascinated by the moving image – film, video. I still have those interests, but over time, painting and collage-work have become more present.

When I was ready to produce my first play, I went to talk to artist Adrian Loving about my process. He suggested that I develop a concept book to better understand characters and the world of the play in general. I followed his advice. That led to me creating collages in a black sketch book. I collaborated with visual artists to create an installation and a couple of video collages for that first play, too. And I learned a lot from them all. Co-creating is also deep study. Around this time, I found myself learning about Frida Kahlo and Ana Mendieta, too. Their stories spoke to me. This was after my divorce and in the midst of a torrid love affair… I think maybe that’s the first time I’ve used that word seriously. Torrid. Anyway, visual art became part of my writing practice in that way. I hardly ever shared anything I was making. Only people really close to me would know if they came to visit me at home. My cousin Sofale Ellis encouraged to start working with pastels as a good way to branch out of the sketch book practice, and I did.

In 2019 I was invited to join a cohort of artists in a program in NYC stewarded by my good friend, artist and therapist Tanisha Christie. Through that program, artists were able to rent studio space in the South Bronx at a discounted rate. I planned to take some time to build an environment to perform inside. But the time there intersected with the pandemic. I had to bring everything home. And it was during that time that I really came into the understanding of how making this visual art is devotional gris gris for me. I am making talismans. I needed to make these prayers, these testimonies to spirit. I need these manifestations of faith urgently during those months of the quarantine. I lost a few people close to me. Some became ancestors. Others just had to go away, or I did. I began committing to larger pieces. I began letting go. I just want to keep making, growing, discovering. It’s medicine for me. It’s also another way of exploring story, narrative, character, texture, tone. I appreciate a process that has different registers. And I feel a sense of immediacy about the importance of building connection through story now. I think our humanity depends on it. The earth will go on. It will do what it needs to do to survive. But we have a lot to shed as human beings on this planet. I believe art is a way to do that. We can find new ways to relate. We can heal. We must critique the powers that seek to drown us out. We can experience deep pleasure and joy.

At the core of my practice, no matter what I am making, I see myself as engaging in cultural work. Toni Cade Bambara introduced me to that way of understanding and living the intersection between the work and my community. I first sat at her feet as an undergraduate student at Howard University. But I resonated with her most deeply the second time I read her novel, “The Salt Eaters.” It shapes and speaks to much of my journey still. That question Minnie Ransom asks Velma Henry at the beginning of the novel still inspires my curiosity about life and how I am being in it for better or worse – “Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well?” I am committed to the beautiful struggle in that respect. I am inspired by poets like Sonia Sanchez, who teaches us to be as committed to mentorship and teaching as we are to making the art. It is the relation of one to the other that most sends me – the reciprocity in the dance of life, the work, trouble, and miraculous possibility we co-create in the process of discovery. I have been an educator for over twenty years. I have taught at several colleges and universities. And, in my younger years, I worked as a teaching artist in public middle and high schools in Newark, New Jersey, Bed-Stuy and Brownsville in Brooklyn, NY, and Washington, DC.

My spiritual journey is also central to who I am as a multidisciplinary artist. I do not think these can be separated in truth. Nor can that spirituality be separated from my political self, my sense of justice, care, and freedom. I was initiated Yayi Nkisi Malongo 17 years ago in the Bronx in the Brama con Brama lineage. I am also an Ifa practitioner who first sat on the divination mat in a Lucumi house. This is who I am. When I am writing or painting or dancing at the river, this is who I am. I stand with those who speak truth to power and fight against genocide and oppression. I stand for a free Palestine, a free Chicago, and a Congo where children know a horizon without war, Sudan free from oppression. A free DC. I stand for our ever-present connection to the ancestors. And I am in awe of the complicated beauty of this planet, the rushing waterfall, the majestic sea, the flight of the cormorant and cardinal, the corner and my mama’s kitchen. I love to laugh with the people. I love to roll up my sleeves and get to work with y’all, too.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

One of the most rewarding aspects of being an artist is the prevalence of change. We get to lean into our visions and curiosities to the point that we are able to express or make something in response. There’s always a horizon to walk toward. There’s always an opportunity to stretch in new and different ways. Perhaps we are simply people who experience life prismatically. People say artists often circle around a few core questions or concerns, but we are expressing our discoveries in a spectrum of colors, or variations of genre and style. To me, that is such an inspired way of moving through the world … to keep on asking “what if,” even when you’re scared. A dear friend and collaborator, Paloma McGregor, once gave all of the artists working on a project with her kaleidoscopes. That brought me such joy. It reminds me of the sense of curiosity and play that we must lead with as artists. The longer we do this thing, the more we have to remember that part.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

Comparison is possibly the worst enemy to creativity. Though so much about our society encourages us to measure our success according to seemingly impossible standards, it is essential that we cultivate a toolkit to keep ourselves from comparing our lives to others. We each have a unique purpose; comparison will take you far away from your own. I raised my daughters as a single mother in the Bronx for 16 years. My family members were not nearby. So, most of the time, I was raising my girls outside of a communal network of support, unless we traveled back down to the DMV to visit. I did not share custody with their father. I had sole custody out of necessity. And, in the years I was raising them, most of the arts and culture communities I found myself in did not make accommodations for children. Most of my peers opted not to have children or waited until later than I did. And I respect and celebrate their choices. But it was often difficult to “keep up.” There were conferences, residencies, and retreats I missed. I didn’t finish my PhD until my daughters were both grown women. So, yes, there have been times when comparison has rocked me to my core, especially in a society that puts age limits on artists’ “emergence.” But I have learned to release those predictions. I have learned to understand my journey as unique, finding pleasure in process, turning away from the award shows, and the deluge of scattered expectations life can become when you only look through one cloudy lens over and over again. While I cannot say that I have cured myself of the experiencing that emotional spiral comparison cause, I am acutely aware of its danger. And I actively practice the return to my center, my voice, and my truth by stepping out there and becoming my own medicine. I commit to making the art. I commit to showing up again and again.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.ninaangelamercer.com

- Instagram: @NinaAngelaMercer

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@ninaangelamercer1269

- Other: https://www.oarinc.org

Image Credits

7. 1. Personal photo by TSE of NAM at The Brecht Forum

2. Photo from Urban Bush Women’s Haint Blu premier at Andre Callioux Cultural Arts Center, New Orleans, LA (2023)

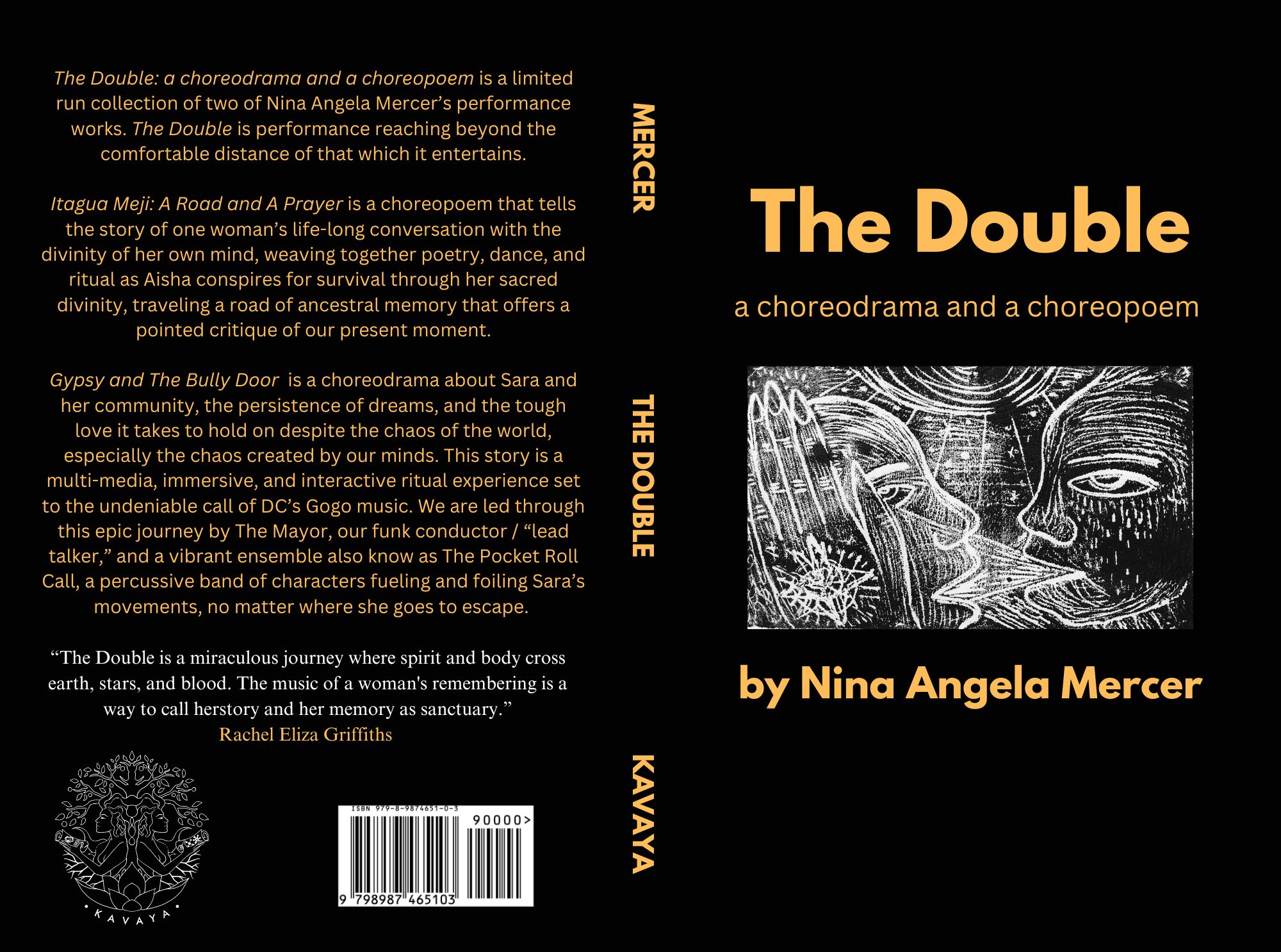

3. Photo of front and back covers of The Double by Nina Angela Mercer (Kavaya Press, 2024).

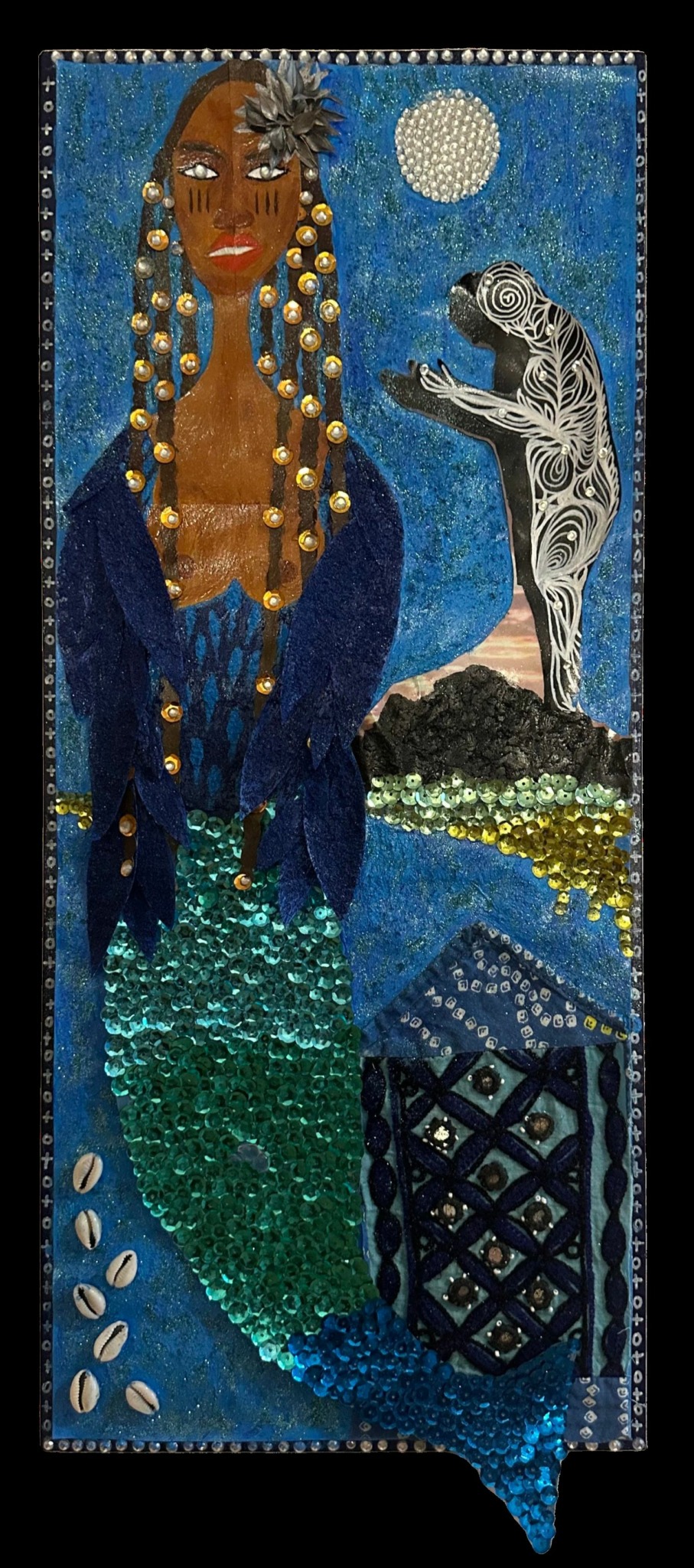

4. “12:12 or Simbi Simba/Hold onto what holds you up,” a collage painting by NAM.

5. “12:12 or Simbi Simba/Hold onto what holds you up,” a collage painting by NAM.

6. “Simbi Simba II,” a collage painting by NAM.

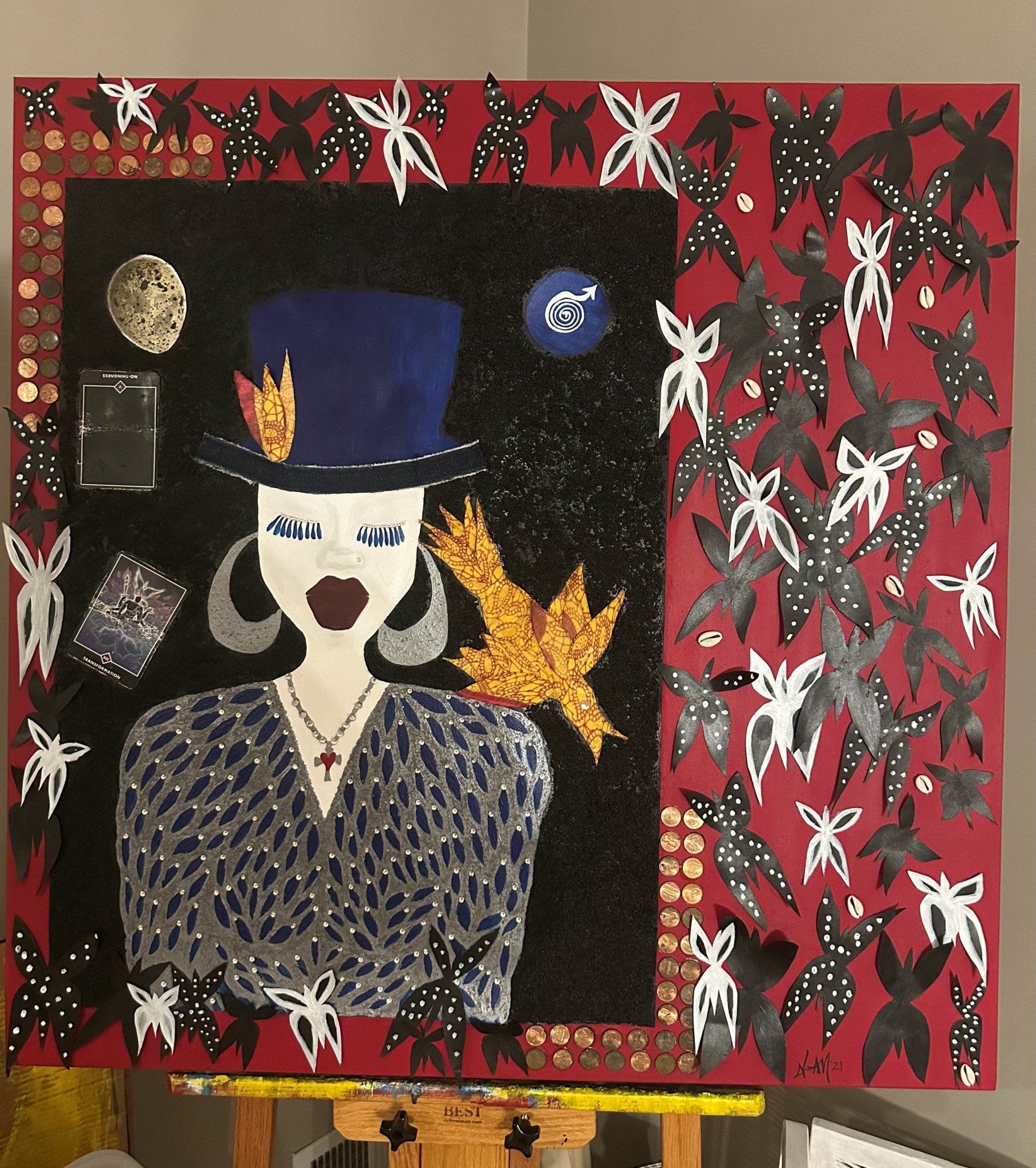

7. “Corona 2020,” collage painting by NAM.

8. Photograph from “Haint Blu,” premiere in New Orleans, LA. Permission of usage from Urban Bush Women.

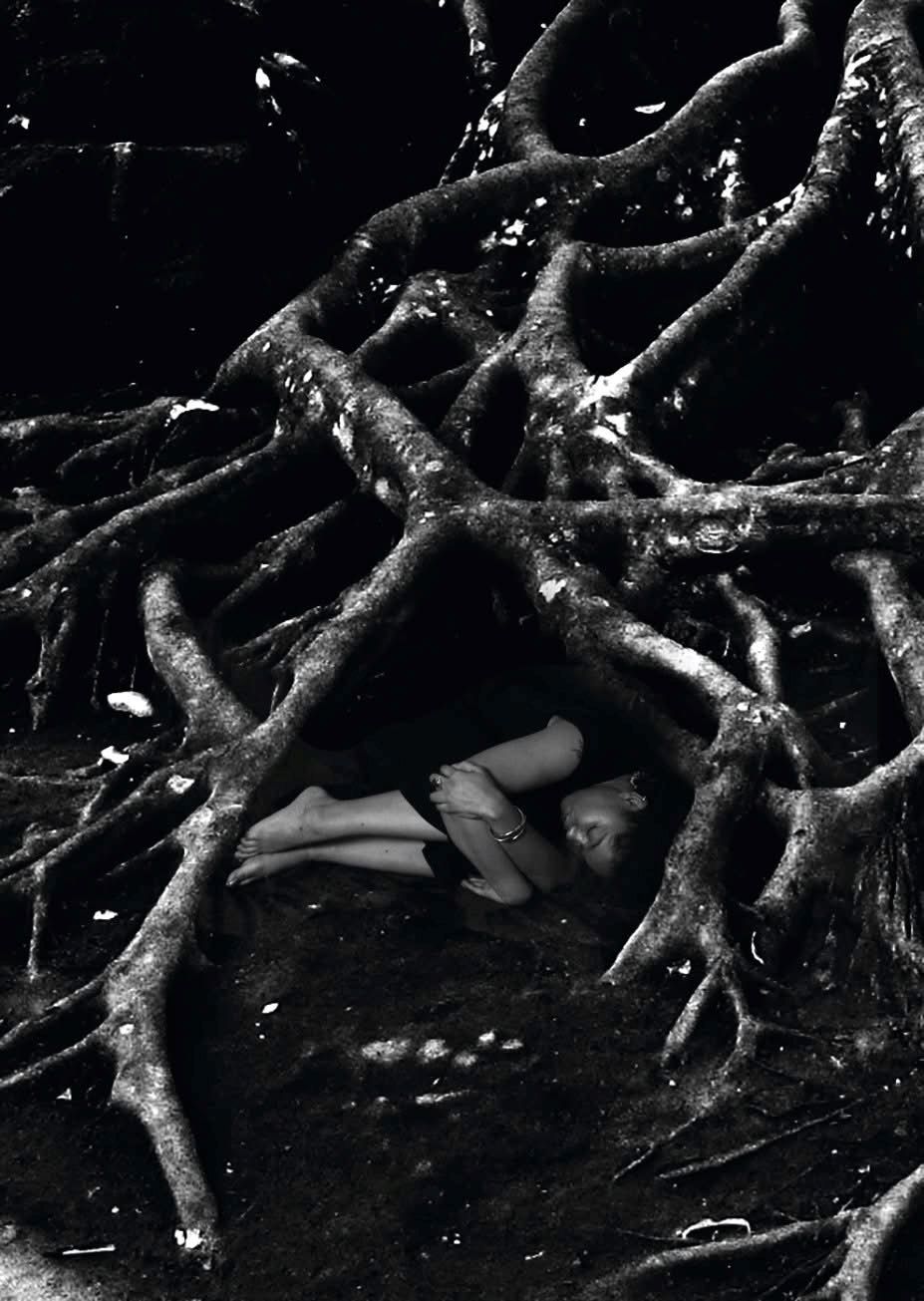

9. Still photograph captured from the video poem/installation “Invocation for Jose Antonio Aponte” from the Visionary Aponte exhibition. Video poem directed by Toshi Sakai, performance by NAM, original photograph of tree roots by Tosha Y. Grantham.

Suggest a Story: CanvasRebel is built on recommendations from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.