We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Natasha Wein a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Natasha thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Can you talk to us about a project that’s meant a lot to you?

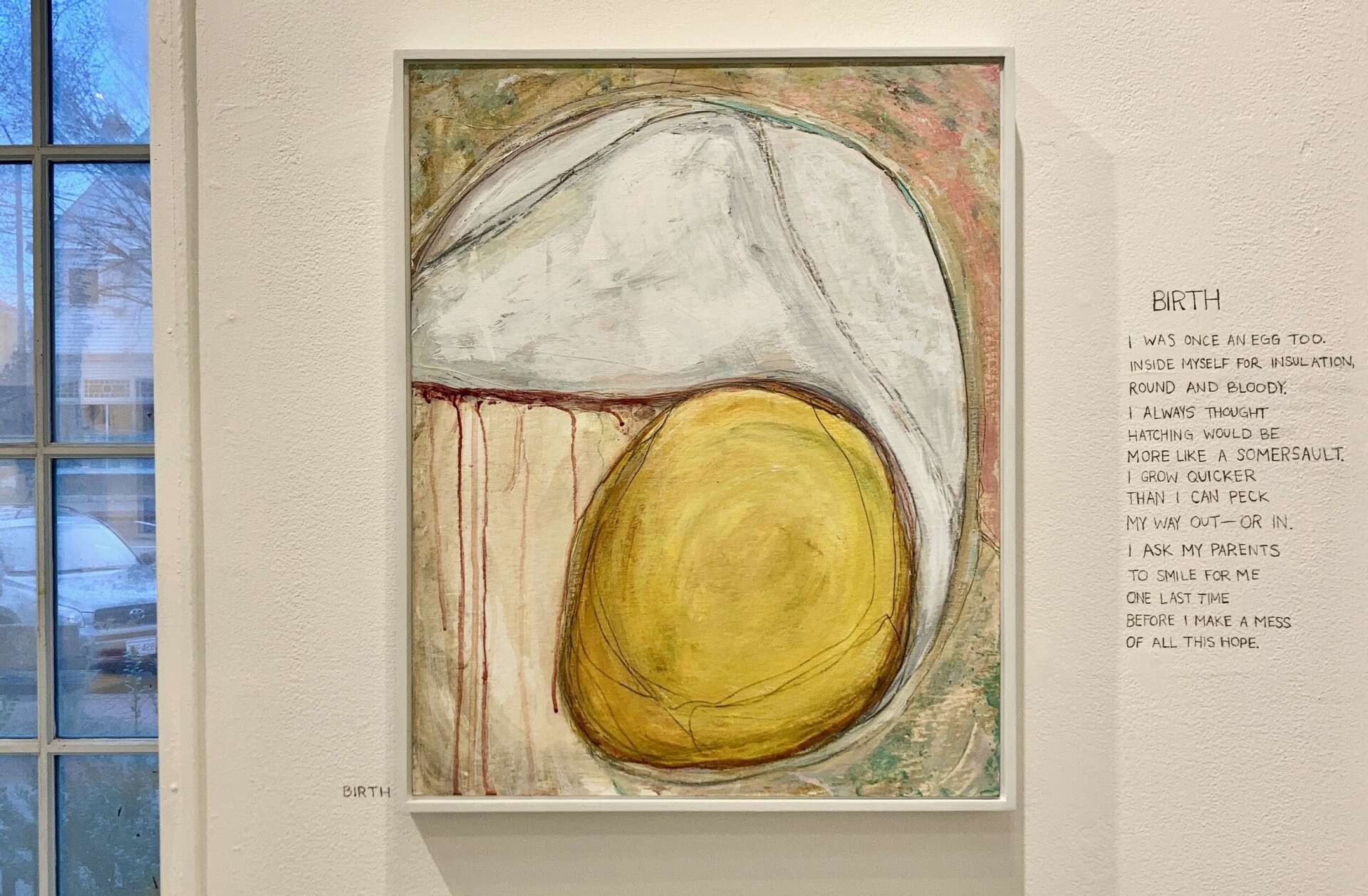

One of my most recent completed projects is an exhibition titled To Be Broken In. The show uses various mediums—abstract paintings, photo edits using real medical imaging, mirrors, poetry, and some small scale installation work—to tell the story of my experience living with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and its related comorbidities. It also challenges cultural perceptions of disability, aims to break down barriers between what we perceive as “normal” and “other,” and illuminates the inevitability of sickness and death.

In 2019, after a rapid decline in my health, I was diagnosed with a rare connective tissue disorder called Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. This condition affects nearly every part of my body, namely my cardiovascular system, immune system, nervous system, and joint stability. Suddenly, I was forced out of the life I recognized and into one of chronic and severe pain, significant disability, and a new set of rules and regulations to live by.

As my usual ways of creating became untenable, I experimented with different creative processes that were in line with my declining and changing function: painting with my feet when my neck injury affected my hand function, audio-transcribing prose, drawing while lying down or walking, pacing with clay and imprinting it into trees outside, making photo edits by overlaying medical imaging with self-portraits while doing treatments, and working at odd hours, including the middle of the night.

This show is a kaleidoscope of the notes and impressions I made in real-time as I bore witness to my own deterioration. It is a collection of little documented moments of my sadness, desperation, isolation, anger, longing, grief, acceptance, and resilience that find reflections in each other. Though it sometimes feels this way, I would be wrong to say that my body is destroying itself; it is preserving itself with everything it knows how and with the same fierceness that I work to preserve the parts of myself that allow me to love.

It’s been three years since I was diagnosed and in many ways I still do not know how to live like this. I have tools now—awareness about my condition, the ability to educate others, and daily physical therapy—but they are not enough. Every day is a practice in finding reasons to love and in not giving up on giving my grief the chance to transform. There is no cure, and despite my laundry list of daily treatments, the closest thing I’ve found to a remedy is the courage to keep documenting my degeneration as it happens in real-time and the strength to keep telling the story of what it feels like to be broken in.

I showed this body of work in a small gallery in Stockbridge, MA. A digital version of this show is available to view on my website. I’m currently working on a series of 30-40 paintings done with my feet and am looking for a gallery to represent this body of work which is an extension of To Be Broken In in terms of themes, but focuses on larger scale paintings with marks informed by ergonomic movements.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

Raised in Palo Alto, California in a cutthroat academic environment, I quickly burnt out and became unwell. The rigorous high-level classes and implicit familial pressure coupled with ongoing complex developmental trauma from my early childhood through my adolescence resulted in my failure to healthily adapt and mature within this stressful environment. I swore off formal education and used my college money to support my creative endeavors and the psychological support I needed to heal and grow up. People often comment on the fact that I am an artist amongst a family of five mathematicians. And while growing up I was very much in the role of black sheep, my work is not as far from STEM fields as people may think. After being raised in a controlling education model driven by the desires of the teachers instead of the students, my love of learning became tangled with expectation, performance anxiety, and dread. One of the greatest joys in being self-employed and rediscovering my fierce hunger for knowledge, is that my life is a vast and constant independent study. I am always learning and reading, specifically articles relating to physical therapy, functional medicine, dynamics related to oppression and activism, math, paradoxes, physics, biology, nature, nutrition, philosophy, psychoanalytic theory, zen buddhism, and eastern models of medicine. These subjects and related themes inform my work in both direct ways (i.e. I sold a painting earlier this year titled Gua Sha: Scraping for Redness) and more abstract ways (i.e. the concept of different types of infinities). I have always been creatively inclined, but as a child academics and my commitment to my competitive soccer team took priority. I never took seriously or pursued my creative interests until 2017 when I moved across the country to western Massachusetts.

I moved to the Berkshires—coincidentally where my father grew up—and began dabbling in various mediums at a communal art studio. In addition to working visually, I experimented with ceramics and fiber in an environment where I largely taught myself, but had mentors to chat with and bounce ideas off of. At first I was drawn to surrealism, using ink and watercolor to carefully render images, usually portraits. My 2018 show titled Synthesis, consisted of 15 surreal extensions of the self and a short book written from the perspective of five internal selves. In this body of work, I experimented with painting and writing from different internal selves in order to understand how the larger system of my self works. In doing so, I connected parts of myself that had been previously severed from one another. At the end of the story, the Peculiar Self writes, “I have always taken an interest in projects that have gotten away from the inventor. Beyond the threshold where the inventor realizes the thing they invented is now larger than their own understanding of the thing, there is a partially exposed world, full of wonder and secrets. And if you bring your most curious and humbled self, and if you trust enough, It will trust you. And slowly, It will reveal itself to be a world you created, that is now creating you.”

My work shifted from surreal to abstract in early 2019 after being inspired by my painting mentor, Maggie Mailer. She taught me how to mix color to work with themes of relationships and boundaries, which became the foundation of my 2019 show titled Origin Stories; “By mixing a little bit of the same color paint into two different colors, you can relate these two colors to one another and open a metaphorical dialogue between them. Every time I nearly ran out of paint, I added new dollops of bottled paint and continued the mixing process, creating generations of paint. As I mixed more paint related to the same ancestors and prepped more boards, I created families of paintings. Like most families, these relationships are loaded with painful and ambivalent feelings: love, hate, need, aggression, desire, longing, hurt, fear, desperation, closeness.” My experiential work with this series helped me further my understanding of my origin story and its points of intersection with others’ stories. I later wrote, “I do not know if it is possible to rejoin the fragments of my shattered traumatized selves, but I have found—to both my relief and horror—one constant throughout all the divorced selves I inhabit and abandon like a nomad in my own life: the pain does not end, it shapeshifts.” Despite working by series, my shows are connected, both thematically and sequentially; each show integrates learning from the previous show into its fabric.

My work has given me a way into myself and a way into the world. This unique psychoanalytically informed creative process I’ve developed provides me with a method to understand and re-organize my psyche as well as a platform to connect to and better understand others. One of the most meaningful parts of my work is listening to people talk about what they notice or identify within my visual and written narratives; we find fragments of ourselves and each other in the human experience and art can be a way to explore individual uniqueness and humanity’s interconnectedness.

I once read that if you want to stop a suicidal person from killing themself, let them tell their story. In this fundamental way, telling my stories—especially painful ones that are challenging to speak in a satisfactory way—using words, images, and symbolic communication has given me an enormous reason to live and love.

At the end of my artist statement in my 2021 show, These Four Walls, I wrote: “We are all in development. These stories are of those stunted parts, how to help them grow up and integrate into our adult-selves, and what we can become if we are brave enough to love what we have been through and bold enough to choose the future-selves we dare believe in. There’s a story I cannot tell alone. I was once an egg too…”

I see my role in the world as an artist to be that of a translator, integrating the internal and the external, as well as the abstract and the physical. My work is heavily influenced by psychodynamic theory; I am deeply devoted to learning about individual, interpersonal, and group processes. I generally work by series creating narrative-based art shows that integrate feeling and language, explore conflicted desires, and expose and reorganize experience in order to make sense of personal and collective origin stories. This way of working is both intuitive and intentional. I honor impulse, free-association, doubt, and the symbolism embedded in the process to create a call-and-response between abstraction and language. Working abstractly lends itself to projection, analysis, and real-time processing of present dynamics. If I knew beforehand what I was going to create, there would be no point in making it, as I would already have integrated the related wisdom and clarity; strictly adhering to previously conceived ideas or images limits learning and discovery. My work is at the edges of intuition and science, abstraction and hyper-intellectualization, and harsh truths and healing. By honoring the unknown, I am able to unearth personal and universal truths and narratives; In this process I shift from translator to storyteller, regaining power over familiar and unconsciously-driven narratives, speaking truths that are more honest, and writing a future that is more fulfilling.

—

My first book of poems, The Stains We Keep, was recently published by Bottlecap Press and is available to purchase directly through me or through Bottlecap Press’s website. I also write freelance, including my most recent published piece in Réapparition Journal about my experience living with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, internalized shame, and cultural perception of disability.

In addition to my work as an artist and writer, I also own a small business called Berkshire Resin Art where I sell nature-inspired jewelry and home decor that I make by preserving locally harvested flora, fungi, and found dead insects in resin epoxy. For more on that project, go to www.berkshireresinart.com or follow me on instagram at @berkshire_resin_art

What’s a lesson you had to unlearn and what’s the backstory?

Two things I hear a lot as an artist are “I can’t make art because I’m a perfectionist” and “I can’t make art because I don’t know how to make what’s in my head come out on paper.” Debunking these myths with my first painting mentor, Mark Mulherin, was an integral part of building a foundation in which I could freely create, breed more creativity, and fall in love with the process.

Perfectionism is a word tossed around that, in my opinion, has completely lost its meaning. When we use this word, we are not referring to an idea of perfection (such a thing doesn’t exist), but rather we are referring to a strict and exact idea we have about an end product. For me—and I think for others too—my early definition of perfectionism was hyper-realism. I thought that drawings and paintings had to look hyperrealistic in order to be legitimate. By challenging my definition of perfectionism, I unearthed the limiting aesthetic beliefs I was holding about art. There are so many ways to render a hand and depending on how you choose to depict it, you capture a certain quality or embodiment of a hand. Egon Schiele’s depictions of hands capture something more sinister when compared to Michelangelo’s painting Creation of Adam which captures qualities of divinity and longing. This is the same for lines; Mark grabbed a scrap piece of paper and drew thick bent lines, light curved lines, fading dotted lines, and an impulsive scribble. Line, shadow, color, and mark making can all be ways of capturing qualities of experience. The ability to hyper-realistically render an object is an incredible skill, but it’s not the only way to capture and translate experience. I find that I am more interested in and moved by art that renders objects and experiences in ways I don’t usually see them like I would through a camera.

The second lesson I had to practice was learning how to relate to my paintings differently. I observed that relating to my paintings with expectation, coercion, control, force, frustration, and belittling produced the same result as if I were to relate to a child that way: shame, frustration, shut down, self-loathing, and withdrawing. Children that are not respected and understood withhold and suppress their true experience. I began relating to my work as if each painting were another being. When I relate with interest, respect, patience, curiosity, and trust, my paintings (i.e. myself) begin trusting me and revealing meaning. I think of my paintings as sentient beings with lessons to teach me and I view them through the lens of learning rather than some made up idea about what art is supposed to look like.

“Perfectionism” is a convenient way to limit ourselves and curtail our potential. By shielding ourselves from creating, we protect ourselves from having to encounter both our true limits as well as our true potential. The latter is arguably scarier to the fearful and repressed self. It seems that the work of creating has less to do with navigating “perfectionism” and more to do with navigating fear. And while we also unconsciously borrow ideas, practices, and mannerisms from other people, we can only make our own art. Everyone is creative just like how all kids are creative; we just learn to stifle our creativity at an all too young age. The process of learning to re-tap into your creativity is one of reconnecting with your inner child and letting yourself express your desires and dreams without judgment and expectation. We are not unique in our fear, but we can be unique in our expressions.

The process of tending to my “creative digestive tract” is ongoing; part of being a creative is also going through natural cycles of creativity and blockages and learning how to understand and work with these rhythms.

That being said, the raw emotional experience related to the “perfectionist” mindset can feel oppressive and suffocating. This is why conversing or working with a mentor can help facilitate development. Though I largely create alone, my work could not be possible without the power of relationships.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.nweinart.com

- Instagram: @nweinart

- Other: My small business is Berkshire Resin Art www.berkshireresinart.com @berkshire_resin_art