We recently connected with Nancy Grimes and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Nancy thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Do you feel you or your work has ever been misunderstood or mischaracterized? If so, tell us the story and how/why it happened and if there are any interesting learnings or insights you took from the experience?

I hesitated before choosing this question for fear of sounding self-pitying and whiny, but I do feel my work has been repeatedly mischaracterized as “realism” even though it is not. An explanation for this requires a short art history lesson.

After the rise of abstract expressionism in the 50s, artists making any kind of representational work were lumped together as realists. Gone were the usual art historical distinctions applied to pre-modernist art. In the past, Realism was a category of representation. It included artists who chose a naturalistic style—one truer to how things looked—over idealist conceptions of form. Realists aimed to present an unvarnished picture of the world around them by choosing everyday and working-class subjects. For instance, Courbet was classified as a realist because he eschewed mythological and historical subjects. The Ashcan artists were realist in their embrace of the lower echelons of society.

Despite this mainstream view of art history, abstract artists and their advocates, in a willful and self-serving reinterpretation of history, labeled all artists who painted images, both living and dead, realists. This wasn’t a compliment. Their argument was that the camera better captured the visible world, so why paint it? “Realists” were considered out-of-step with their time and, in the words of the late art critic Robert Hughes, had “missed the bus” of art history. Like a person falsely accused of a crime, a representational artist had to live and work under a cloud of shame. They were aesthetically incorrect.

When I first entered the scene in the late 70s, the situation had improved. Artists like William Bailey, Jack Beal, Janet Fish, Sylvia Mangold and Philip Pearlstein had turned away from pure abstraction in favor of representational images that drew upon modernist and formalist conventions. They looked new and fresh and gave younger artists permission to make art that wasn’t just about art. Yet, despite the success of this “New Realism,” I remember, as I struggled in my studio, a constant barrage of negative criticism. Throughout the late 70s and early 80s, I was condemned as “retardataire”, “irrelevant,” and “ahistorical.” My work was stale pastiche and, according to one visitor to my studio, “stupid.”

Things have changed since then. Now there is an explosion of representational painting—a sort of a return of the repressed—and I can’t help feeling smugly self-satisfied as the wheel of art trends spins in my direction, proving that I was right all along about the relevance and appeal of images.

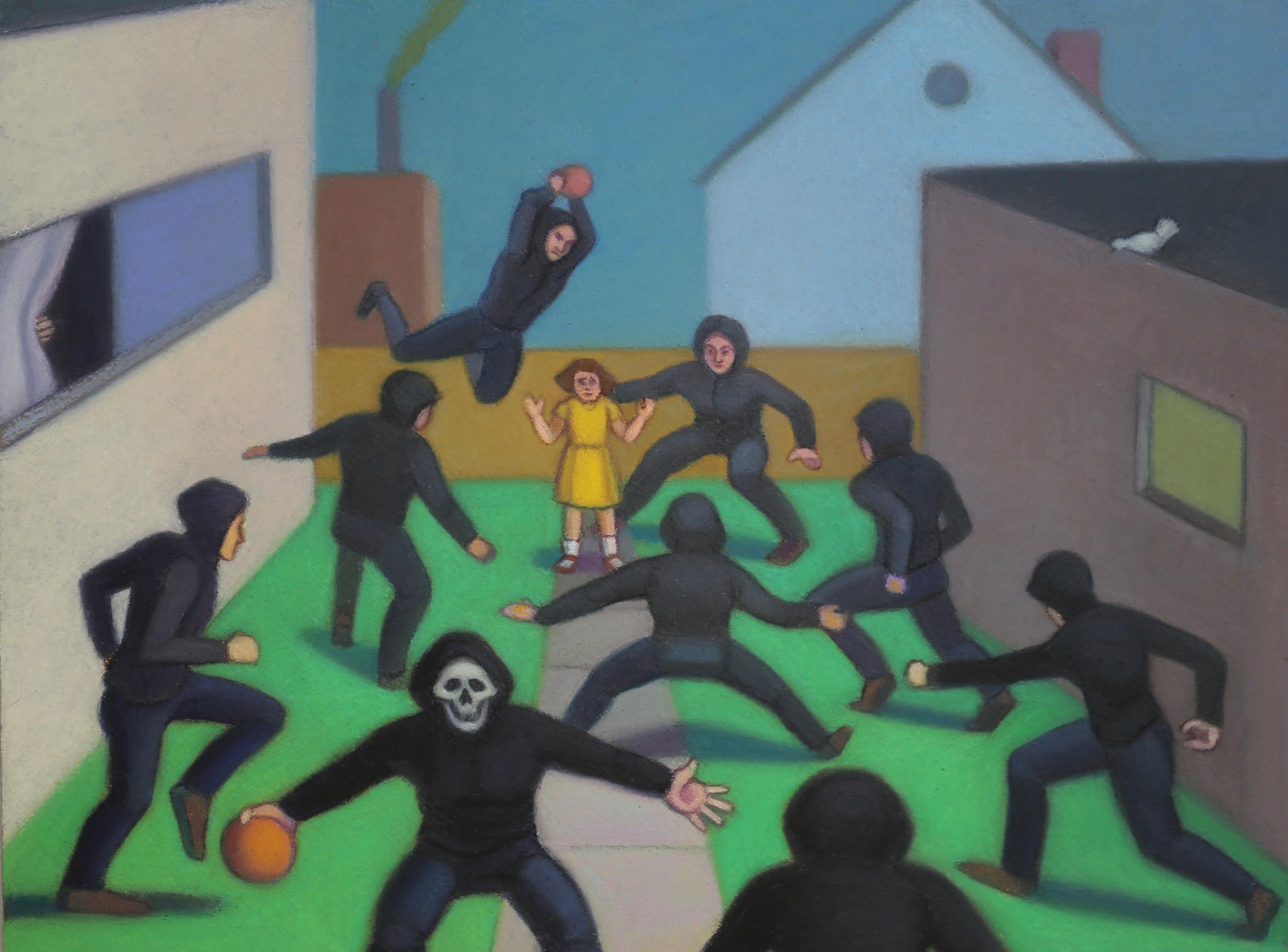

I still feel, however, that I have missed the bus. I may be just too old now. Most of today’s notable figurative painters are younger artists working in either photographic or cartoony styles that are essentially flat. In contrast, my work is still pictorial. I paint form and space. My shapes have volume and weight and exist in spaces that go back and forth as well as over and across. Half observational and half from my imagination, my current work is rooted in Magic Realism and is more mannerist than realist. Nevertheless, the vestiges of naturalism that remain set me apart form younger figure painters, who still, to my dismay, see my work as realism.

Nancy, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I’m a baby boomer from the Midwest. My family was lower middle-class teetering on poor. As a child, I had to field calls from creditors, wear hand-me-downs and constantly borrow lunch money from friends. My parents, in their youth, had been hipsters and they carried into adulthood a low tolerance for rules, religion and the opinions of others. My father was an amateur musician; my mother, an appreciator of painting with a good eye. Both read and sketched and valued the arts. In our house, artists were looked upon favorably, and I knew I wanted to be one from a very early age.

Thanks to Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, I was able to get grants and loans for college. I studied studio art and art history at Indiana University in Bloomington. Heavy-hitting artists like William Bailey and Robert Barnes taught there at the time, and the Fine Arts department actively encouraged painting representationally. The only conflict I encountered was between disciples of Picasso and those of Matisse—a sort of drawing versus painting debate, which seems silly in retrospect.

I began graduate work at the University of Chicago. The art department was third rate, but my spouse William Grimes and I wanted to attend the same school, so Chicago was it. The art history there was fantastic, though. I took courses with Joshua Taylor and Harold Rosenberg, both first-class minds. It was here that I began to butt heads with non-representational painters. Most of the other students were into abstraction, as was my teacher, Vera Clement. I constantly had to defend myself and became insecure and exhausted from arguing with my classmates. After a year of this, I dropped out, became ill, and took an extended leave. For a good portion of this period, I was bed-ridden and had plenty of time to mull over my artistic values and beliefs. I spent my days reading art magazines and drawing nearby objects like wadded up Kleenex. When I was finally ready to return to school, I was convinced that there was no good reason not to paint what I wanted, and I wanted to paint things in the world. All the arguments against this seemed specious—political justifications for one type of art over another with no sound basis in history or fact. Armed with a renewed commitment to my inclinations, I resumed my graduate studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—a real art school, where I eventually got my MFA.

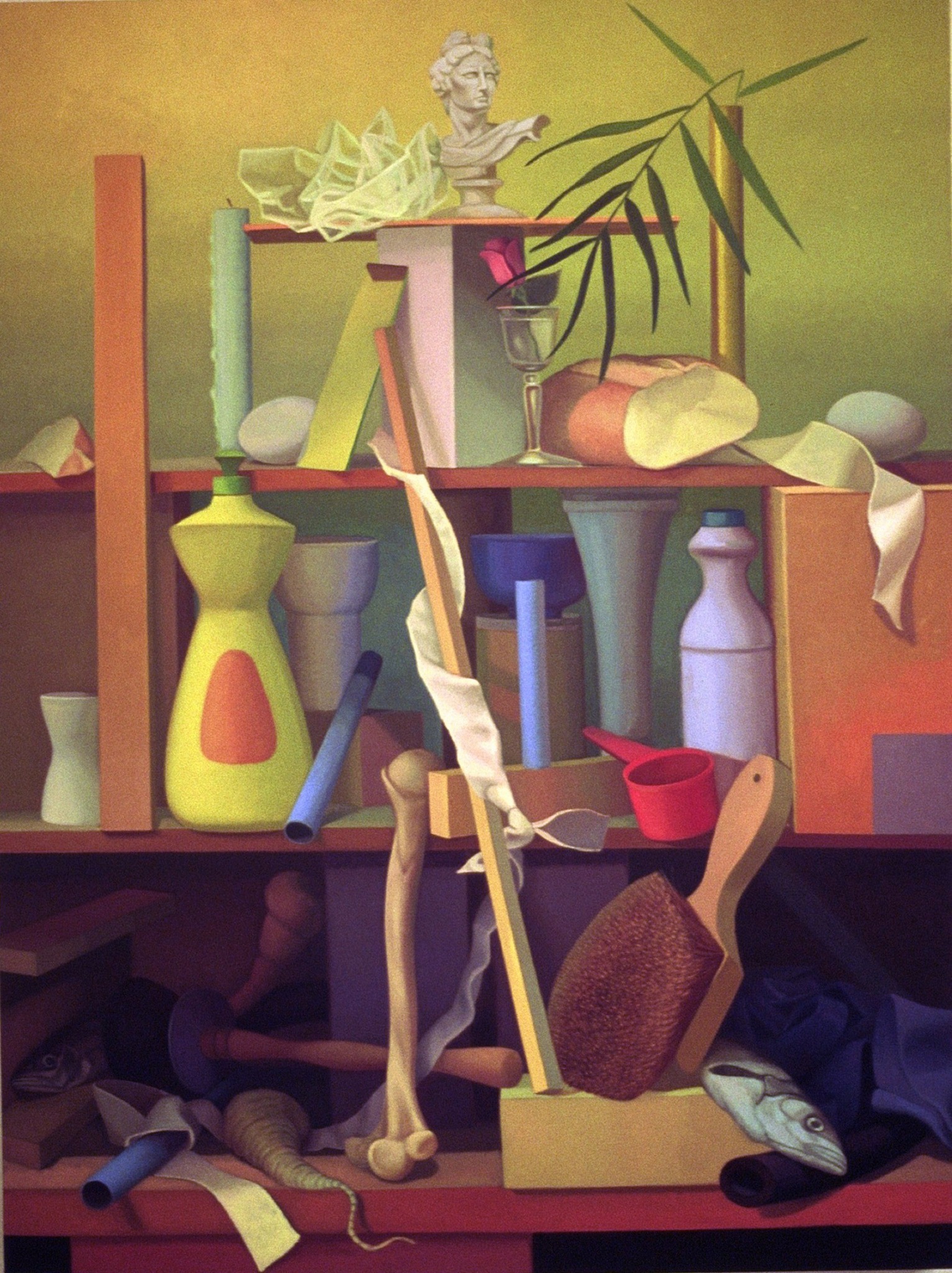

I began painting still life in grad school. Influenced by minimal art, I painted shallow-spaced pictures of building materials like bricks, pipes and wooden boards. After I moved to New York City in 1980, I continued to paint still life, expanding my repertoire of subject matter to include studio flotsam, dishes, food, trash and sundry dollar-store type objects. My studio—a small bedroom in a three-room apartment—was littered with blocks of wood, pipe fittings, plastic fruit and old cardboard towel and toilet paper rolls. During this time, I dutifully visited galleries, attended openings and sent slides of my work to dealers. My first nibble was from Alan Stone, whose Upper East Side gallery showed artists like Richard Estes and Wayne Thiebaud. Stone looked at my work and told me, in so many words, that I didn’t know how to paint. Crushed, I scurried back to my studio, cried, got mad, and eventually realized that he was right. I didn’t know how to paint but I was determined to learn.

I think the realization that I didn’t have the chops to make the paintings I wanted and my resolve to stop pursuing gallery representation and learn how to paint for real are the things I am proudest of. It seemed to me I had two choices. I could figure out a way to paint that didn’t require much painting knowledge or I could do the hard work of becoming better. I could devise some trendy strategy that might (or might not) get brief attention, or I could commit to the long haul of learning to understand my craft and its history and, by doing so, better equip myself to discover who I was as an artist.

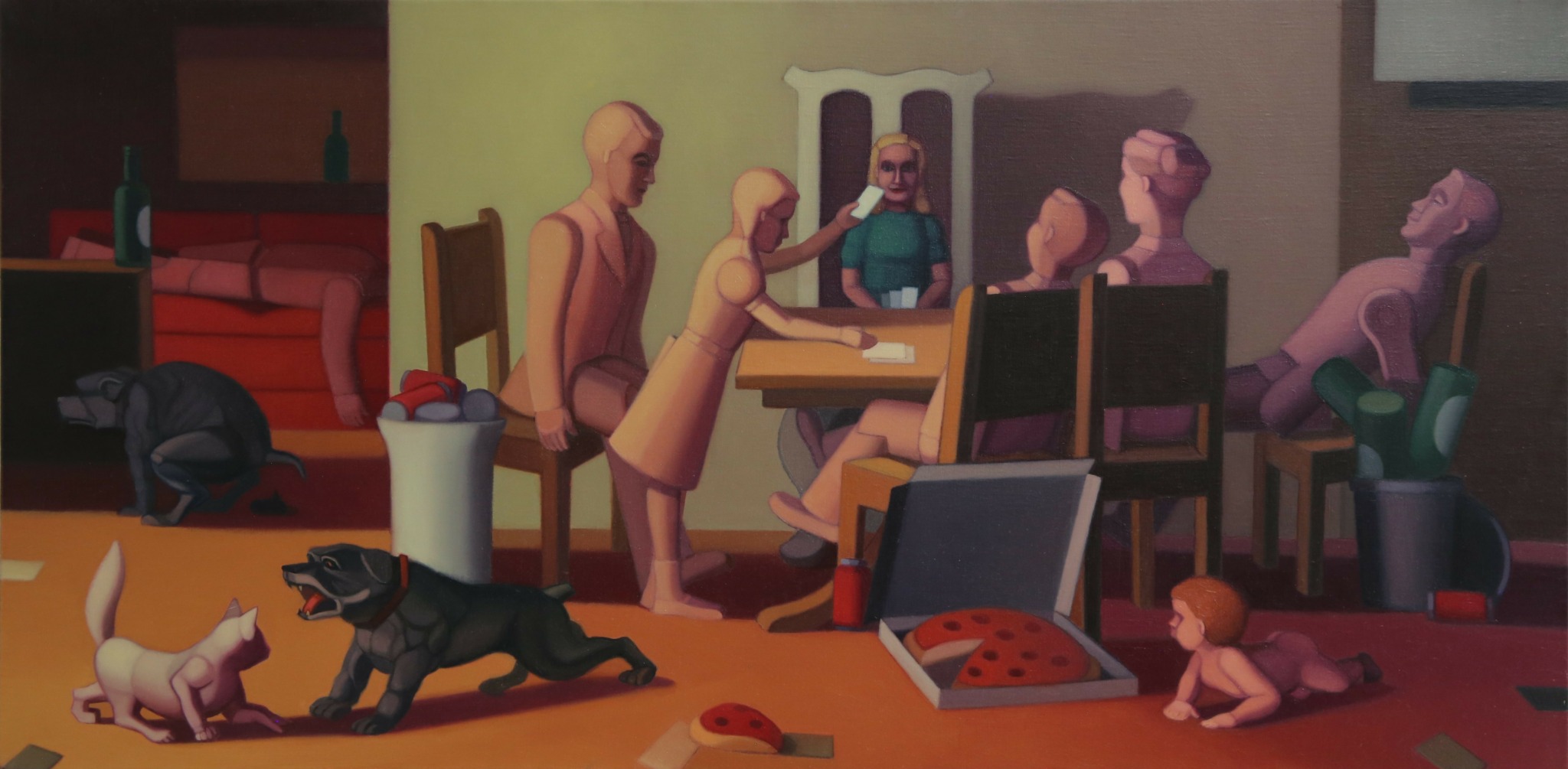

I consider the mastering of painting a lifelong endeavor. If that makes me a perennial student, so be it, but for me the process of learning went hand in hand with the growth and maturation of the content of my work. After two decades of painting still life (which I still strongly advocate), I acknowledged that I was a closeted figure painter. I wanted to make works that talked more directly about myself and my experiences in the world, and to do this, I needed to paint people. For the last 12 years or so I have made work based on my lower-middle-class upbringing, my friends and family, my tenure as an art professor and my health. Although originating in autobiography, I hope they say something larger about who we are as human beings.

Can you tell us about a time you’ve had to pivot?

Although my path as an artist has been fairly straight, I’ve encountered a few bumps and swerves along the way. In terms of my work, I’ve switched gears twice. Both times in ways that were somewhat self-destructive. By the end of the 80’s, I was tired of the essentially formalist still lifes I was painting—neutral objects stacked across the canvas on makeshift, grid-like scaffolds. I wanted something more intellectually challenging and deeper in feeling and meaning. I had been studying all types of still life and found I was especially drawn to 17th century Dutch vanitas painting—allegorical still lifes that depicted memento mori—objects like skulls and bones that reminded viewers of life’s brevity and the inevitability of death. Influenced by these works, I began making my own vanitas paintings, partly in response to the AIDS epidemic. Now, paintings about death aren’t popular, and the art consultants and dealers who had been sporadically selling my work shied away from my allegories, and my trickle of sales slowed to a drip.

The second change occurred about a dozen years ago when I began painting figures. I was already using objects like decoys and mannequin heads as stand ins for figures, and the works were becoming more personal and autobiographical, so it wasn’t a huge conceptual leap. I lost my brother, sister and mother in a relatively short span of time, and I realized that I had been painting surreptitiously about them. My mother was the last to go, and after her death, I felt compelled to look back at my rather unhappy childhood and paint about my family’s dysfunction. I hadn’t painted figures since college and felt intimidated by the formal/technical challenges of figure painting, so I eased into it by painting dollhouse dolls and furniture arranged in tabletop tableaux. At first, I painted the dolls as playthings but I quickly realized that I didn’t want the toy association. Now, I paint the figures as figures. I still begin with crude arrangements of dolls, action figures and mannequins, but I paint them as real people in real spaces–not realistically, of course, but not cartoony or overly stylized either. They fall somewhere in between, I suppose. Making this work has been both challenging and satisfying, but at times it has felt like starting all over again. I am still in the process of learning a new painting vocabulary and, after losing a good portion of my still-life audience, I need to find new outlets for my work. Still, what’s important to me is to make a body of work that I feel good about. I just hope I live long enough to finish all the paintings I want to make.

Have any books or other resources had a big impact on you?

When I was at the University of Chicago, I wrote a paper for Joshua Taylor’s 20th century art history-class on Mark Rothko and myth. He gave me an “A” but, at the bottom of the paper, noted that he didn’t think I knew what myth was. I panicked. Was he right? Did I not know what myth was? My notions about myth came from the writings of abstract artists like Barnett Newman and were pretty vague, so I decided I needed to look into myth a little deeper. I began reading everything I could find on myth—books by Mircea Eliade, Joseph Campbell, Ernst Cassirer, Suzanne Langer, Freud and Jung. Jung made the greatest impression on me. His writings and ideas are artist friendly, and his theories on the collective unconscious and the symbolism of dreams influenced Magic Realists like George Tooker and Jared French, artists I admire and have written about in catalogue essays and gallery reviews. I even wrote a book on French called, “Jared French’s Myths.”

Contact Info:

- Website: https://nancygrimes.net

- Instagram: https://instagram.com/nancy.grimes

- Facebook: https://facebook.com/nancygrimes

Image Credits

Michelle Lee Photography (picture of Nancy Grimes in studio)

Malcolm Varon NYC (Custody)