We recently connected with Mona Mengnan Chu and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Mona Mengnan, thanks for joining us today. Did you always know you wanted to pursue a creative or artistic career? When did you first know?

I think the first time I truly knew I wanted to pursue a creative path was when I was still working as a journalist in China. I was trained to observe and record reality, but very often I felt that the most powerful parts of people’s lives were invisible in the headlines; they existed in emotions, gestures, and silences. I started to realize that film could capture those dimensions in a way reporting could not.

One moment that stands out was during the production of a documentary about ordinary families. I was behind the camera, following a mother and child, and I suddenly felt that the camera was not just a tool for information, but a bridge to human intimacy. That moment shifted something in me: I wanted to move beyond documenting events and instead create stories that could preserve and transmit emotional truth.

That realization pushed me to leave a stable career path and take the leap into filmmaking. It was both terrifying and liberating, but I remember thinking very clearly: this is the language I want to spend my life learning.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

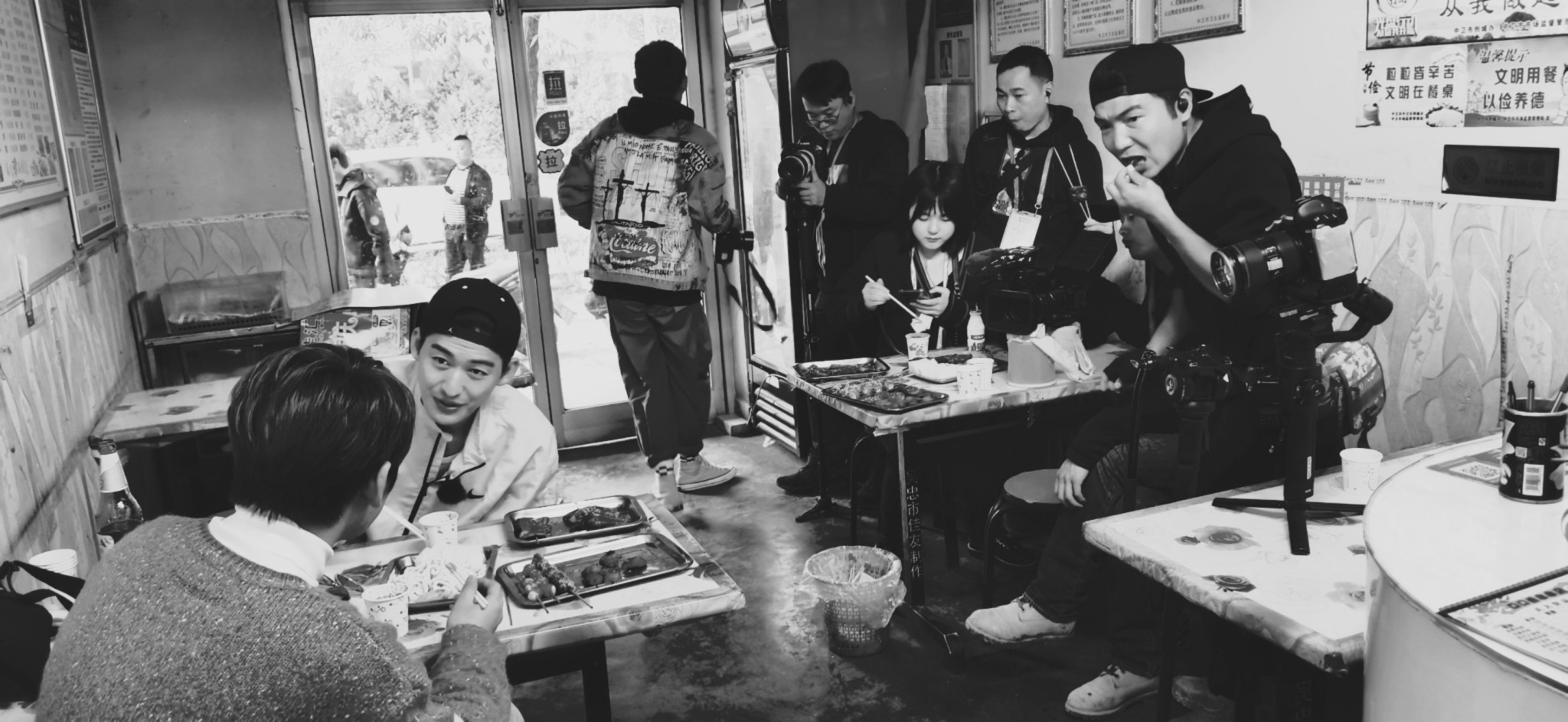

I actually started out not in film, but in journalism and later television. For many years, I worked as a director and writer of unscripted shows in China. One of the projects I am most proud of is My Little One (Wo Jia Na Gui Nv), a reality series that I created, directed, and wrote, which went on to be nominated for Best Reality Show at the Magnolia Awards at the 2019 25th Shanghai Television Festival. The series became a cultural phenomenon in China, sparking widespread conversations about women’s independence, family expectations, and modern urban life. That experience showed me how powerful storytelling can be when it taps into real social issues and emotional truths.

But at the same time, I felt that reality television had its limits; it could reach billions of viewers, yet there were still stories I wanted to tell in a more intimate, layered, and artistic way. That’s what pushed me toward filmmaking. In 2017, I directed my thesis documentary film Four Chapters of Solitude, which was selected by the 13th Beijing College Student Film Festival and the China-EU Film Festival. It was the first time I felt the language of cinema opening up to me, allowing me to explore solitude, memory, and identity beyond the frame of TV formats.

Since then, I’ve been developing work across both fiction and nonfiction, always exploring the “in-betweens”, between documentary and narrative, between East and West, between personal memory and collective history. My approach is shaped by that unusual path: the sharpness of journalism, the reach of television, and the intimacy of cinema.

What sets me apart, I think, is my commitment to sincerity and empathy in whatever form I’m working in. Whether through a popular TV series that touched millions or a small independent short that quietly traveled the festival circuit, I want my work to open space for reflection, dialogue, and connection.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

For me, the mission has always been about creating work that builds empathy and makes invisible stories visible. Growing up in China and later working internationally, I became very aware of how many voices are overlooked or simplified, whether it’s women navigating independence, young people in transition, or families caught between tradition and change. Through both television and film, my goal has been to give those stories space, depth, and dignity.

I’m also driven by the idea of bridging different worlds, East and West, fiction and nonfiction, personal and collective. I see cinema as a way to connect experiences that might seem distant on the surface but are profoundly human at their core. If my work can spark recognition, dialogue, or even just a moment of empathy in someone who might not otherwise encounter that perspective, then I feel I’ve achieved something meaningful.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

I think the best way society can support artists is by creating the conditions for them to take risks without fear of survival. That means fair funding structures, grants, and accessible resources so that art doesn’t become something only the privileged can afford to pursue. Creativity requires time, and time requires some degree of security.

Equally important is building platforms that actually listen to diverse voices. Too often, the spotlight is given to the same stories, while new perspectives remain on the margins. Supporting a thriving creative ecosystem means valuing difference, opening doors to underrepresented communities, and making sure their stories are not just included but taken seriously.

And finally, I think audiences play a huge role too, by being open, curious, and willing to engage with work that challenges them. A healthy creative ecosystem is not only about artists making work, but about society being willing to grow with that work.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.mengnanchu.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/monaachuu/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mengnanchu

- Other: https://www.5reveursfilm.com/

Image Credits

Hunan TV