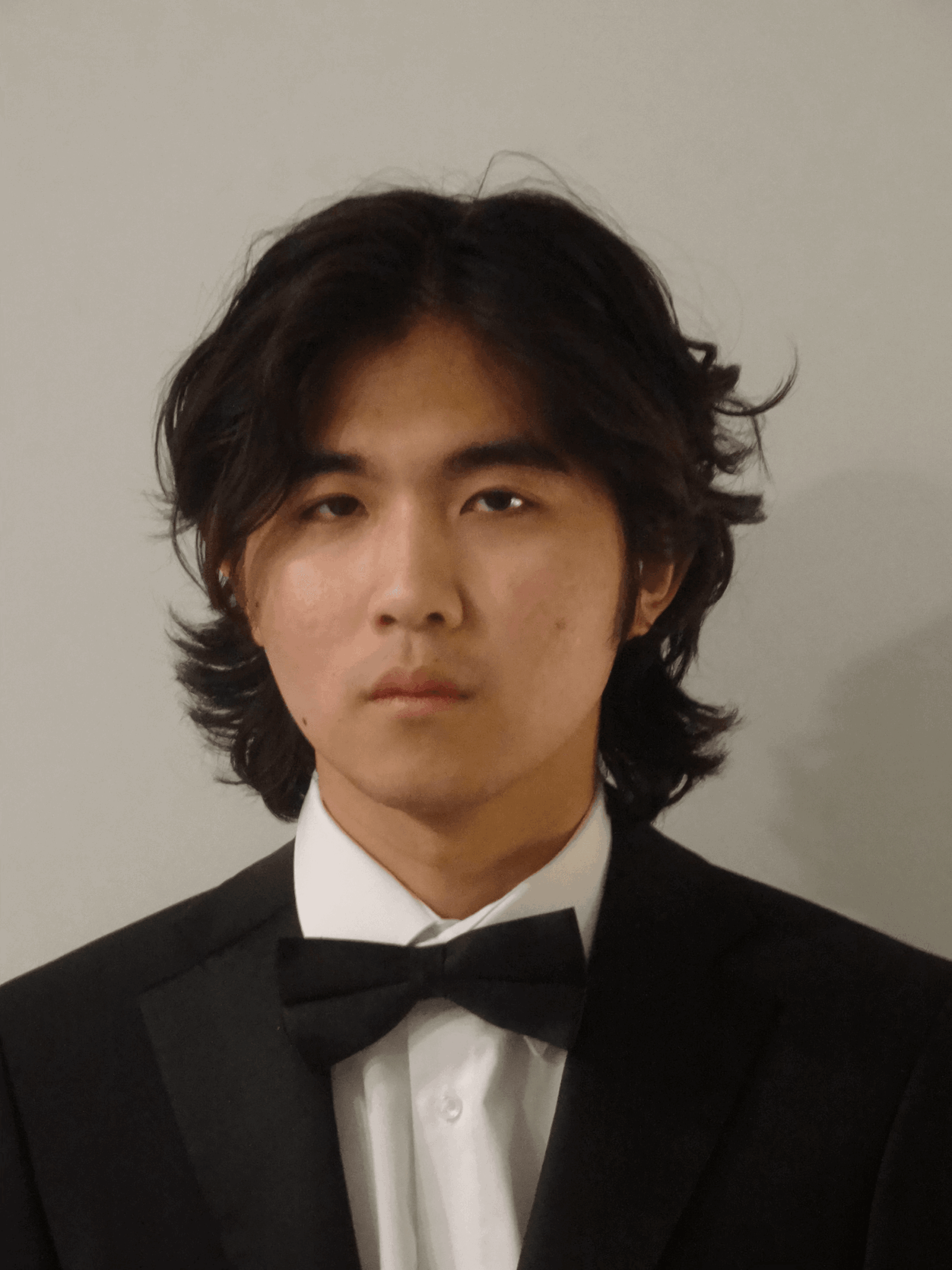

We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Min Kim a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Min, appreciate you joining us today. Did you always know you wanted to pursue a creative or artistic career? When did you first know?

When I was in kindergarten in Korea, we did an activity where we had to answer basic questions about ourselves on a piece of paper – from my favorite color to my favorite animal to what I want to be when I grew up. For most people that’s probably when you first become privy to the notion of identity. The funny thing is that now I don’t remember any of the things I wrote down – I don’t remember things like my favorite color or my favorite animal that my effervescent baby mind would have conjured up – except I do remember what I wrote I wanted to be when I grew up: a movie director. I have no idea why I wrote that.

But then again I imagine it’s because I loved movies. By the time I moved to the US with my mom in middle school, it had become a quite cemented mission for me to become a filmmaker. There was no one poignant moment. There was no bifurcated road. It’s almost a religious concept. You worship the divine truth you’ve always known, that you were born to bear, and you surrender to be an empty vessel, for the ocean of ideas, the breath of cinema.

My childhood was sustained by the backbone of cinema, saved by cinema at each points on the brink of collapse, then formed a symbiosis where I couldn’t live without it, for better or for worse. I was watching movies everyday since I was in elementary school. To an average boy in Korea and an immigrant boy in America – weighed down by the vacuous lands harboring you, by the empty spectacle of the fast changing world, cinema taught me how to reckon with the insoluble failures of existence, and gave me a glimpse of a world in which expressions of such feelings can be possible, imperative, and potent. I recall an interview that Truffaut did, where he posited that he considered watching all those movies as a young man during wartime as an apprenticeship. I see it less in practical terms and more so in a spiritual way – cinema taught me how to love myself, and it taught me how to love others. I have no intention of doing anything other than give my life and career to cinema.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I went to USC School of Cinematic Arts twice in consecutive years, majored in Cinema Studies in undergrad and in Film Production in grad school. At a place like that, and I assume this is the case for many film schools, you’re inadvertently indoctrinated to the notion that filmmaking is a trade more so than art. By all means, you need skills. But it’s not as clear-cut as “mastering the craft” because you’re making art. In making films you don’t learn the discipline to make the immaculate product that supercedes the rest. The question is in finding yourself as an artist, which is an everlasting process. This is the bare minimum.

Growing up I’ve come to realize that cinema is a visual medium at its most boring when it’s about salient things. My interest is in the invisible reality, whether it’s the invisible things that circulate around us to form an intangible inner life, or it’s the very form in which the image we see is communicated, denoting the temper of a medium itself. Assayas said – “Cinema is about resurrection. Cinema is about dealing with your own ghosts and bringing them to life.”

What Assayas said of Cinema gives importance to everything that is dead, everything that is static, imperceptible, and meaningless, because then they are simply waiting to be channeled through the spectral intermediary of the camera. My job is as an interlocutor, for the shaking revelations about myself and the world at large that cinema laced into my subconscious. Godard would show me how visual language can be revolutionized, or be revolution itself. Rohmer would teach me about the ambiguities and delusions of human relationships, including my own. And Chantal Akerman would rewire the way I perceive my reality, and show me the ways in which cinema can reflect that reality – and its transgressions.

As a writer-director I’ve made short films – mostly in the bounds of USC film school. In a film production course, I made a 20-minute short inspired by a chapter from Michelangelo Antonioni’s book, Quel Bowling sul Tevere. Titled The Story Teller, the film depicts a screenwriter visiting a city, stricken by ennui and writer’s block until he sees a mystery woman outside the window thereby finding “inspiration” from her image. When I first read Antonioni’s piece it had inseminated in my brain the idea of an epic that is like a glimpse into an artist’s mind – all its hubris, darkness, and dangers. It was fun to write and direct a film whose structure and form mirror the exact hauteur and its subsequent breakdown within the main character – the point was to construct a Rohmerian/Bressonian world though film language where a montage of some pictorial images, verbose and heavy dialogue, prevail in the first half, only for it to be dismantled when a certain revelation eventually saps the artist’s authority. In the latter half, the woman approaches the screenwriter and tells him she had been watching him as well. She felt a need to tell him her story. Now the film becomes a basic shot-reverse-shot of two faces. The screenwriter listens, shocked by the power and truth of her story. He is at once rendered powerless and enthralled. He ruminates that night alone, finally deciding to write. The next morning we see that he has written nothing. Antonioni’s source material depicted a day in his life where he encountered a woman who told him a story. Loosely inspired, I expanded it into a grand tale leading up to a simple joke. Joan Didion said we tell ourselves stories in order to live. The farce of humanity is that we – artists or otherwise – really tend to only hearken to the stories we tell ourselves.

The following year, I was admitted to USC grad school for Film & TV Production. In the first semester I created a black-and-white dreamscape relationship drama titled Monkeys Like to Smoke Too. In the film, a couple wanders the fever-dream-like interior of an apartment. The woman’s body is there, but her mind is far away, bewitched by the memory of a love affair. It’s a love story with a haunting, maybe even a ghost story… It is often the custom of film school to tell you what is cinematic or not. For instance, they may eschew ambiguity as a marker of weak visual storytelling, or deem a talking cinema anti-cinematic. But I knew, based on what learned from the works of Antonioni to Ozu to Rohmer to Resnais… that those things can also be titillating, send shock waves through the spine… perhaps even more so than what a studio manual would tell you. So a thought occurred to me to design a film that amalgamates the seemingly-uncinematic with the cinematic. Long monologues. Vague mysteries. Story told through memories and dreams. I wanted to prove that through a directing prowess, they can also be rendered into a vital and enchanting visual experience. Film schools would prime you for a mechanical reproduction, of ideas, of language, of forms, of consciousness… and we’ve entered a stage where everyone can tell a unique and personal story, insofar as they tell it the same way. But I subscribe to the notion that every moment in film is a part of a dialectic. Every choice in a film can be a sort of statement, a part of a thinking cinema, an organic creature.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

I am particularly fond of films that are actively creating a friction with the audience, to challenge them. This can mean many things. One might think “challenging” movies means movies that show things that are hard to watch because they’re shocking or graphic or slow. But truly challenging images carry challenging ideas – challenging to the thing called “logic” that our everyday reality conditioned us to operate on. Logic is like a drug we take daily to numb us from discontents and irregularities. The idea that A causes B, which causes C which causes D. This is the ideology of maths and sciences. But life’s complexities and ambivalences often reject the easy equation of cause and effect, and art must be true to life. Consider, that A causes B, but B may have caused A, and C just happens arbitrarily, and D makes A null, or makes it full, depending on how you’d like to see it. To a comfortable mind expecting answers to line up perfectly, uncertainty is like a violence. We are pathologically wired to champion things we can easily understand. But the most peculiar, visceral, and therefore valuable human emotions occur as a reaction to the things and feelings we don’t quite understand. Logic gives us security, while uncertainty makes us go astray in our emotions, knocks at our subconscious and affects us for a hopelessly long time. After all, when we can finally accept that things are not so understandable by logic, wouldn’t we be able to truly understand each other by our feelings?

I’d like to make films this way. I am currently in pre-production to to shoot a film that I’ve written, called Movement. The film takes place on a surreal, empty vacuum of a desert land, with nothing but a straight dirt road stretching endlessly. A boy and a girl meet on the road, each of their intentions, their goals, unknown to the other. The boy is reticent, albeit resolute. The girl is more experienced, but jaded. They form a union in this rendezvous and walk together towards the end of the road, in the hopes of finding what they want there. They walk and talk, not even knowing for certain which way is forward and which way is backward, and not knowing if “the end” really exists. Logic tells them they need to get to the end, but the mysteries of one another and of this journey, and the infinite, indifferent landscapes swaddle them like a monstrous irony. We know nothing about these people, where they come from, or where they’re bound to be, as much as they know nothing. The central metaphor of this conceit is a movement that only highlights the stillness of it, and moving images that acquiesce their filmic space to introspection. Many questions loom at large and haunt the film. Will they get to the end? Will they find what they’re looking for? What are they looking for? Who are they? Do they even know? In this world, the biggest, the most devastating mystery of all is the mystery of the self. No matter what kind of film I make – genre, scale, subject matter – I will always make films with this same essential DNA, films whose friction with logic results in a confrontation with the brutal human truths latent within us. Because it relieves me, touches me to see it, and I’m sure others who recognize it may feel the same. I may never be able to truly reckon with myself, and with everything I don’t understand, but I will be okay as long as I can make movies about them, for cinema is a medium in which that hopeless reality can find its own language to be entangled to.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

We’re living in a time where being a sellout is now the default. Even 10-15 years ago you may have been made fun of if you thought “getting your bag” is your life’s calling. It’s telling that supposedly the most expensive film school’s priority is not teaching you how to make good art but teaching you how to sell your product well – not that it even helps, because there’s less and less visibility for great young filmmakers who come from nothing (I recall hearing Gregg Araki say that going to USC film school showed him for how soulless and anti-art Hollywood would be). I don’t have an answer to what society can do to support artists. Personally I’ve been out of any meaningful work since getting out of school for a long time, and I can speak for all of my peers as well. My question is what can society do for us, for me? What can you do for me?

Contact Info:

- Website: https://vimeo.com/user27372650

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/minkimmm01?igsh=NTc4MTIwNjQ2YQ%3D%3D&utm_source=qr