We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Matthew Woodward . We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Matthew below.

Hi Matthew , thanks for joining us today. One of our favorite things to brainstorm about with friends who’ve built something entrepreneurial is what they would do differently if they were to start over today. Surely, there are things you’ve learned that would allow you to do it over faster, more efficiently. We’d love to hear how you would go about setting things up if you were starting over today, knowing everything that you already know.

I graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago in 2005, and immediately went to grad school at the New York Academy of Art, graduating in 2007. Chicago and New York offer vastly different kinds of lives for an artist, each equally generous if you can dial into them. Breaking into New York’s world-bending, institutional network is a life-long goal for some, it’s a skill-set that requires dedicating huge amounts of time and energy to shaking a lot of hands and breaking into social circles. But once you’re in, operating within those circles makes the rungs of the ladder an easier climb. For the “reclusive artist” type, like me, I just wanted to be in the studio all the time, developing my body of work, tracking down the vision. Any time away from that life felt like time wasted, but I knew then like I do now that the art world is about connections, and you can’t rest your laurels and build a career merely on the merit of a beautiful drawing or painting.

I bounced between each city for a year or so, trying to decide which life I wanted, and I landed in Chicago with my eyes on the prize, determined to do both. I would spend a decade working in Chicago and make my way back to New York with an undeniably beautiful body of work and a strong resume. Within a year or so I had landed in a well known gallery. Gallery representation was (and still might be) a major goal of mine, but as a young artist a year out of grad school I had managed a major achievement. I was attracted to (and distracted by) the title and status and all the professional baggage that comes with representation. And something that escaped my attention then was that being a part of a gallery’s roster is the same as entering into a business partnership, and at the core of that partnership there must be a bright set of boundaries and expectations in place to help guide this partnership.

This particular gallery was very well respected, and they were good to me. They made a number of huge sales that supported me in my early years, but there were also components of my career that needed attention, things that I regarded equally important to sales. Like farming the art world’s illimitable connections for more shows, placing my work in important collections and museums, or interviews in magazines to help exercise my working ideas in print, etc. These are the building blocks of a successful, sustainable career in the arts, a foundation for longevity. But I was wrapped up in the glamour and romance of representation, and couldn’t zoom out to see the bigger picture.

I had, of course, necessarily pounded the pavement on my own behalf long before and during representation but being absorbed into a gallery I had a number of presumptions in place. For instance I thought that my success meant their success, and, as a brand, in lifting me up they lifted themselves. As far as getting the attention of museums and collectors, the artist really can’t do that alone, they need a connected partner to lead the way, they need introductions, meetings, etc and this was (to me) the most important feature of representation (access to a network), and naturally, I presumed, part of the deal. I presumed my success was a mutually beneficial component of our relationship, a part and parcel loop. But it wasn’t. And I had not done my duty to communicate effectively that it was the one thing I sought the hardest. After a number of really nice solo and group shows, the collectors and museums never materialized, and as time and years went on without them, and despite more shows, I should have gracefully parted ways with the gallery and looked for other representation, other outlets to help me get what I needed. For whatever reason I stayed. I kept my nose to my side of the grindstone hoping things would change, knowing they would not.

If I could go back and start over, I’d still begin my career in Chicago, I’m proud to have cut my teeth there, but I would push off the enchantment with representation, and I’d do more to keep my options open and forge my own connections, rather than wait for someone else to show me the way into the world I expected, whether I had the power to access it or not. And I would not have accepted representation until my needs were satisfied. All the signs were there that no amount of communication on my part would change the way the gallery worked, they had their own vision they were sticking to, which is totally fine. It means that our partnership could only operate in a limited capacity, and that’s my responsibility to check and attach to which an expiration date.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

I am a rabbit hole diver. My work is very much based on personal experience, and it’s something that I’ve been exploring for twenty years. And I’ll spend the rest of my life trying to understand it, and making work out of it. Sharing it. Mainly, I’ve always felt near me the sense that I am not actually inhabiting the moment my body is in, which I attribute to an endless realignment of patterns of grief buried somewhere in my life. I don’t think this is a unique experience. If it’s the artists job to create form out of the nature of the task with the means of our time, then what else is there but rabbit holes to share? This is mine.

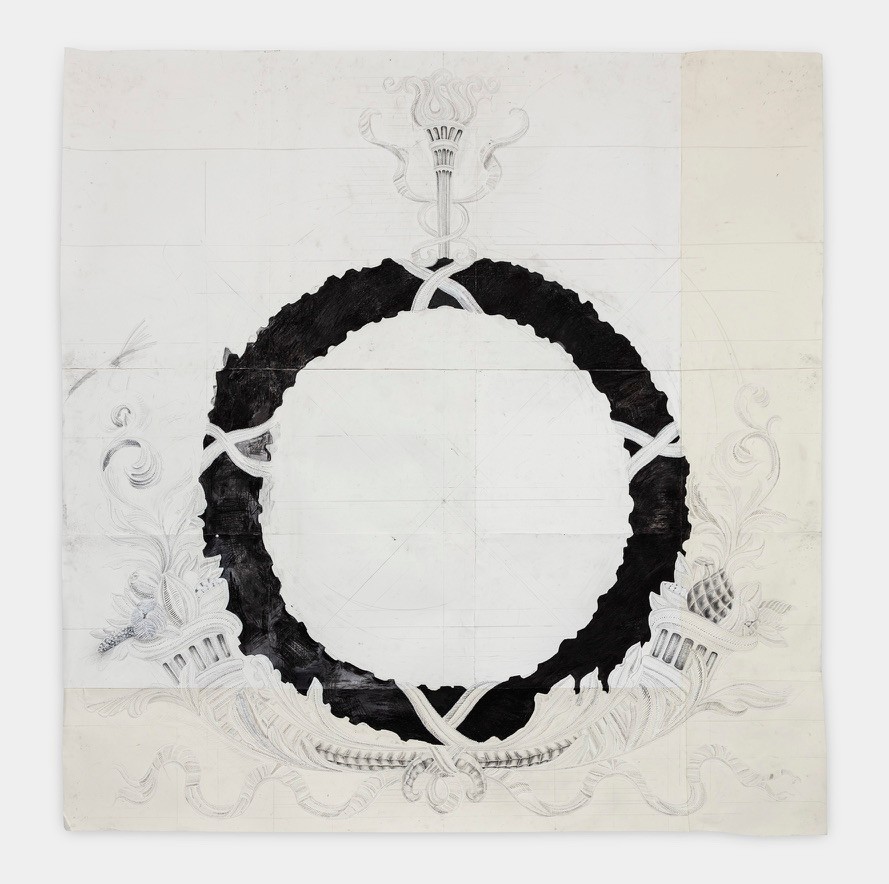

I am a visual artist, I make drawings. When I moved to Chicago from Rochester I was overwhelmed by the kinds of buildings I encountered, and the way they moved in and out of time. It was as if by operating through another language laid over space they were able to distort and delay chronology, history. The present. I felt both in and out of place among them, as if the buildings belonged to a world behind the world, which I too slipped into and out of when I walked with them. When I began to try to make sense of it, I leaned into making drawings. The immediacy and brevity of the mark, its ability to encase even a tiny moment through the strike of a pencil, the way that mark as a material is an indelible trace of a moment, the moment of movement, of working, of drawing, each mark never completely arriving and, movement upon movement, even as a finished piece never actually complete. Just like the built environment. That sense of beginning, constant beginnings, is what lead me to understand this as an experience of grief.

And, on the other hand, this way of looking at the world, of walking through it and being there with it, helped me reinsribe my environment, it brought me back to myself. Or it brought the world back to me.

I’ve been making drawings of that moment ever since. Ordinarily I use architectural imagery as my subject matter. Specifically ornament that is extremely familiar to us, and that has a very specific function within the building itself. It both indicates a function of construction while simultaneously embodying a more poetic function, one that steps through time and readies, in a glance, an array of cultural associations at the surface of a moment. It’s almost anthropological. The ornament are also pieces of a larger conversation that’s constantly acquiring new meaning. Throughout my work, a focus on changing materials facilitates that conversation in an effort to recontextualize and reclaim the ornament, as an image, from a problematic architectural lineage and transform the nature of its task.

Moreover, unhinging the ornament from its everyday life on a building and bringing it to the surface of a drawing, removing it from its commonplace changes it, and I’ve always viewed this action as a generative one that carries within it the capacity for renewal. By coaxing from within the ornament material imaginaries that step out of the code of its convention, there is signaled a reinvention. Reinvention requires surrendering, relinquishing inheritances, withdrawing from them, rather than staying obedient. In this way the ornament as an architectural moment is given new life, new light through which to view it and ourselves.

We’d love to hear the story of how you turned a side-hustle into a something much bigger.

My Side hustle absolutely became my full time business. I work in coffee, at a beautiful restaurant in Harlem called Dear Mama as a barista. I’m the Director of Coffee there, and I’m very lucky to have found them.

I had gotten myself into a kind of over-rigorous, sealed-in studio practice when I was in Chicago. For over a year I was working all the time, every day from the moment I got up until I crashed, and rarely seeing anyone or engaging with anyone, not even the small family of friends I lived with. And, through a kind of communication entropy, I had actually began to lose the ability to speak or socialize deeply in general. I was turning inward, hardening. A friend of mine one day convinced me to come see him at his shop where he was a barista. I sat neat the bar while he worked and we just talked and slowly a kind of electricity built up in my body. A slow ticking quickening. It was extremely nourishing, and I realized I had forgotten how badly I needed to just be around someone, a community, even if just to talk shop and say nothing, just be there. Be seen. Say hello. A little contact goes a long way, I remember I walked home feeling tired but widely refreshed, like a little personal Spring had opened in me. I got back into my studio like a beam of air and when a job opening appeared at my friend’s shop I took it.

Over the years, I jumped in and out of the Barista world, taking jobs at an array of shops when the money dried up, each shop leaning into a different form of hospitality, and each approached coffee along different lines of utility and seriousness. Personally, I love coffee, but serving it requires a finger to the pulse of an ever-evolving landscape of equipment, brew methods, and commodity trends. At the heart of it, however, one thing stays the same: coffee is community. It brings people together and for this it’s universally beloved and defended.

I started at Dear Mama in September of 2016, and eventually worked my way up to the top as the Director of Coffee. From here I keep tabs on everything from hospitality to brand identity and quality control. But, much like being an artist, for the shop as a business it’s the hard-won relationships we’ve built and maintained over time that have kept us alive. Every opportunity to serve someone is an opportunity to connect with them. We survived and scraped through the Pandemic by pivoting creatively on a dime like everyone else but, at our core, simply being available to a world that had closed the door on itself, that had gotten accustomed to sensing their community disappear, was what kept us alive. Our doors stayed open for the entirety of the Pandemic, providing a place where you could come in, grab a coffee, and just check in with someone. Be seen. And our community has not forgotten that, they’ve kept us going.

This is my side-hustle-turned-business, and I’m very proud of the place we’ve built. There’s just nothing else like it. Come see us.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

I’m very proud to be an artist. It’s a responsibility and a service I don’t take lightly. I belong to a lineage of humans that reaches through history, that’s intricately connected to the heart of the world, and that provides us contact with a resonant language of energy and meaning. Art provides a way for the world to understand itself, to understand where it’s going, where it’s been. It helps us understand each other, it helps us heal. I like to say that there’s nothing you know about yourself that an artist didn’t teach you. There’s no greater responsibility than taking on those pressures and channeling them into something as essential as an experience that we can use to hopefully better live with love, and to better learn from each other. Being an artist means being in service to a greater collective that’s useless without us each working together.

Contact Info:

- Website: MatthewWoodwardArt.com

- Instagram: @Vonkumpla

Image Credits

Photo Credit, Daniel Greer