We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Matthew Braunginn. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Matthew below.

Matthew, appreciate you joining us today. Earning a full time living from one’s creative career can be incredibly difficult. Have you been able to do so and if so, can you share some of the key parts of your journey and any important advice or lessons that might help creatives who haven’t been able to yet?

I have not been able to; I’m currently working on trying to break even. This means I’m balancing a full-time job in a field I enjoy, along with creating art, which I also love. I’m still learning the business side of it all. Still, being based in Madison, WI, there aren’t many collectors in the region looking to support early-career artists, or opportunities to develop relationships with those who do. It’s not impossible, just quite difficult. In the Midwest, there are more opportunities for people whose work fits better in more craft-focused art fairs and that circuit, but not those that fall into more traditional “fine art.” The main hurdle is finding those relationships and networks, and then developing them. However, I think this highlights a broader issue in promoting those involved in the fine arts, namely the extent to which everything hinges on gaining an “in” with the right collectors and galleries. This benefits those who are natural networkers, and hampers those like me who are neurodivergent.

Matthew, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I don’t come from a traditional artistic or creative background; I studied political science and history in college, still working within the socio-political world—this is a reflection of the family I grew up in, a mixed-race family centered on social justice, on making communities better and stronger. But creation was also part of my family. I played the saxophone and Jazz in high school; jazz was a constant sound throughout our childhood home. My parents and sister also play instruments, and my sister attended art school before pursuing a different direction for her master’s degree. But my great-grandfather on my maternal side of the family supported their family painting through the great depression, there’s a jazz trombonist on my dad’s side of the family, scientists, lawyers, and judges.

So, this influence was there; music was, and is, a large part of my life. I’ve always had a love of film, and I was first struck by visual art when I visited the Dalí museum in Florida around the age of 11. So the creativity was there, but I didn’t see myself as such. Then, about seven years ago, I had an urge to start creating, so I bought a set of paints and began experimenting. After a few months, it evolved from a small hobby, with some natural skills in color use, to something more substantial; it grabbed me and became an obsession of sorts. Now it is something I need to do.

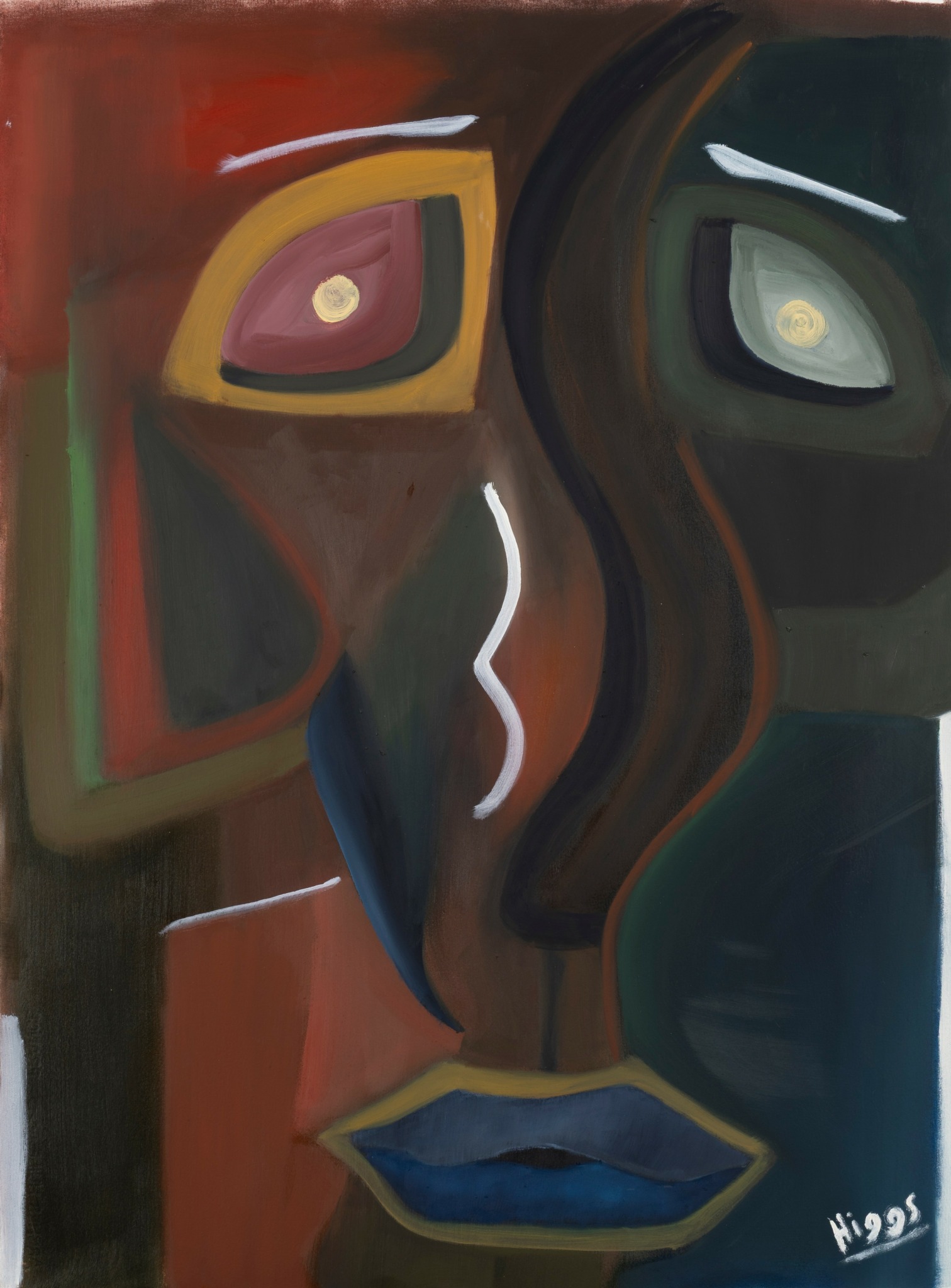

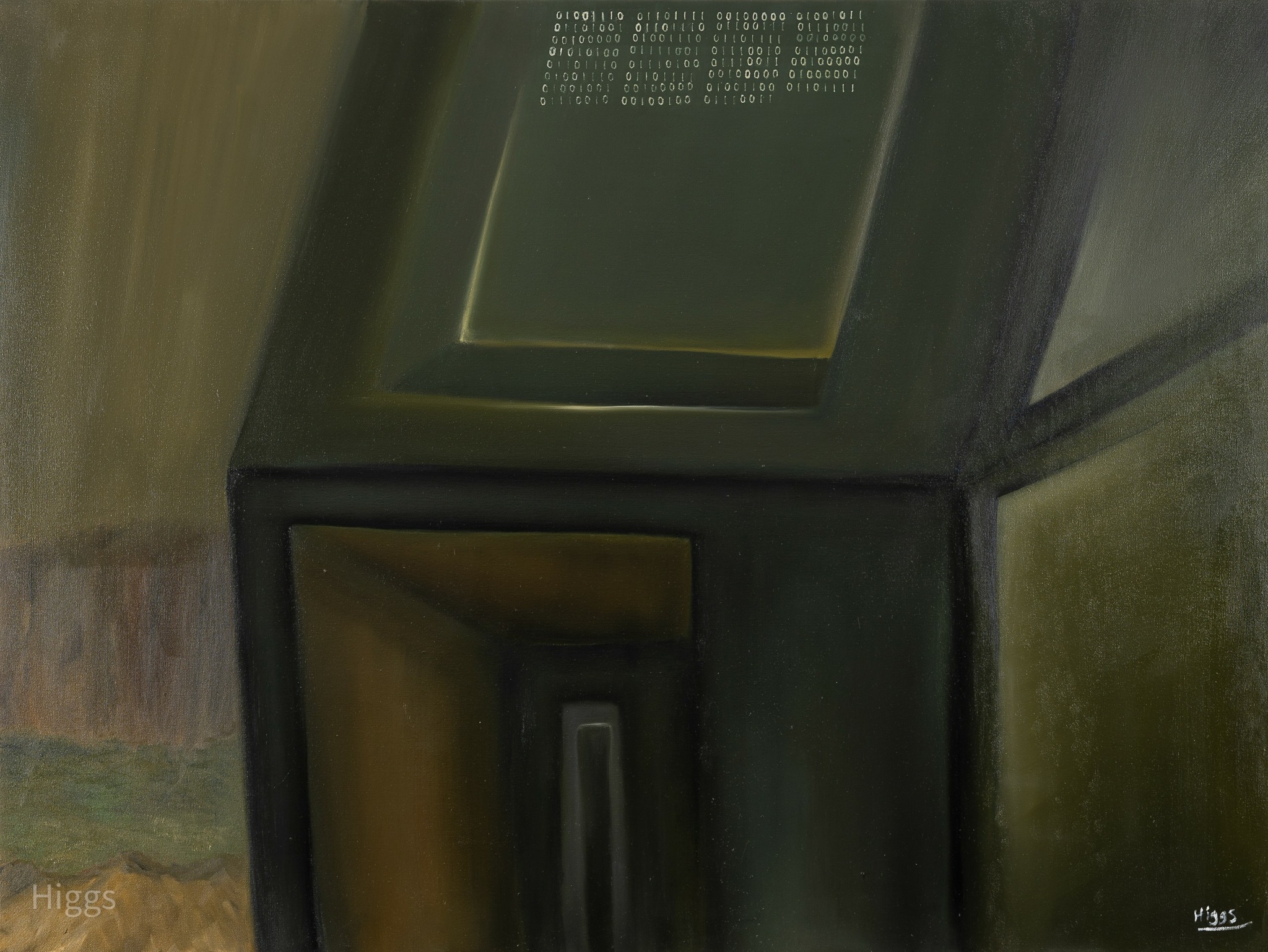

Over the years, I started to find my voice and style as a painter, with a main throughline of my palette and weight abstractions. And in time, my work has evolved into an exploration of what might be called contextual expressionism —a meeting point between my internal world and the external, whether it be interpersonal relationships or global events. In doing so, they are a presentation and reflection of the context in which their creation exists, forcing the world and those observing my work to see the world, the context in which they exist, including both the good and the bad.

Yet, the socio-political is in my work; I see this work as a response to art as an aesthetic during a time of rising fascism, destruction, anti-intellectualism, AI slop, and genocide. In doing so, they have become a masculine act of creation, when masculinity is being presented as domination. Even the heavy musical influence is evident in my visual art, woven into its DNA through genres such as Jazz, Hip-Hop, R&B, Funk, Soul, and many others. The music is injected with the emotionally expressive weight of my subjective interaction and observations of our shared existence.

While rejecting the rot of the modern world through expressionism, they compel observers to confront the complex emotions of simply being, learning to feel and express freely, instead of practicing avoidance of our world.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

There are two intersecting aspects: the pure act of creation, where it channels through you, and, on the other end, something you made. You get to sit there, look at it, and experience something you created. But then, once that happens —once it is done —while it is your creation, it is no longer yours to possess, but something for others to experience. And those two are my favorite things, seeing and experiencing something that I created. And then, seeing others experience it, seeing their emotional reaction and engagement with the work, and in that moment, each time someone experiences it it becomes something new all over again.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

There is so much work and time that go into creating; I don’t think non-creatives understand the level of dedication, skill, and emotion that goes into making something. So many want the end product, want to experience it, without respecting all that went into it. It’s almost like people feel they could do it themselves, so they devalue the end product—especially if it isn’t done by someone already established and known. In each piece, it isn’t just the time put into creating it, but the hundreds and thousands of hours from previous works, successful or unsuccessful, that go into each piece.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://braunginn.com

- Instagram: TheHiggsTape