We recently connected with Martha Patricia Giovine and have shared our conversation below.

Martha Patricia, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. When you were first starting out, did you join a firm or start your own?

I didn’t join a firm—I joined a newsroom, and later, a small group of translators committed to making a difference in immigration cases.

I’m a journalist and a translator, specializing in the translation and certification of documents submitted by asylum seekers before U.S. immigration courts. I also work as an interpreter during asylum hearings.

Both journalism and immigration court interpretation have taught me the profound responsibility of telling a story accurately and credibly. These two professions revealed just how critical an accurate and precise translation must be—often making the difference between protection and denial for someone fleeing persecution. That realization led me to join a certified translation service focused on asylum documentation.

My experience in both the media and the courtroom taught me that translation must be handled with responsibility, care, and deep respect for the story being told. Judges don’t read the original documents—in Spanish, for example—but rather the English translations. And in many cases, the decision hinges not only on the testimony, but on the accuracy of those translated documents.

Going back to where my story in journalism, interpretation, and translation evolved:

Becoming a journalist for print media was an easy choice. I’ve always loved journalism. I’m deeply curious—genuinely interested in people’s life stories and the events that shape them. Journalism gave me a way to connect with people I wouldn’t otherwise have met. It enriched my life in ways no other path could have offered.

Before journalism, I worked in public relations for government agencies focused on child welfare. But in 1995, El Diario de Juárez—the most important newspaper in the state of Chihuahua, Ciudad Juárez, and El Paso, Texas—launched a call for applicants. They invited people from all professions to apply for a two-month intensive journalism course, after which six would be hired as reporters.

At the time, I had a pending job offer in public affairs and I realized too late that the application period for the journalism course had closed. I decided to call anyway and ask to speak with the person in charge. A journalist—now a writer and professor at UTEP—answered and said, “Sorry, the deadline passed a week ago.” I replied, “But would it hurt to meet and talk for just a few minutes?”

He kindly said, “Alright, come over now.” When I arrived, he explained that the course had already begun, and they had narrowed down the initial 120 applicants to 60. Then he added, “Well, now you make 61.”

After nearly two months of classes and several rounds of eliminations, I was hired as a reporter covering the U.S.-Mexico border. That’s how my journalism career began.

My first assignment was to interview a young woman accused of killing and dismembering a couple and their baby. She had refused to speak to the press, beyond one initial comment. I became immersed in her case, studying the legal file and getting to know her family. Eventually, she agreed to an exclusive interview. That article launched my career.

A couple of years later, a former El Paso Herald Post correspondent, who didn’t know me personally but read my articles, reached out. He was stepping down from his post at the international Spanish-language news agency EFE and encouraged me to apply. That same day, I sent my résumé and two writing samples. A week later, I was hired as a correspondent for one of the most prestigious Spanish-language news agencies in the world.

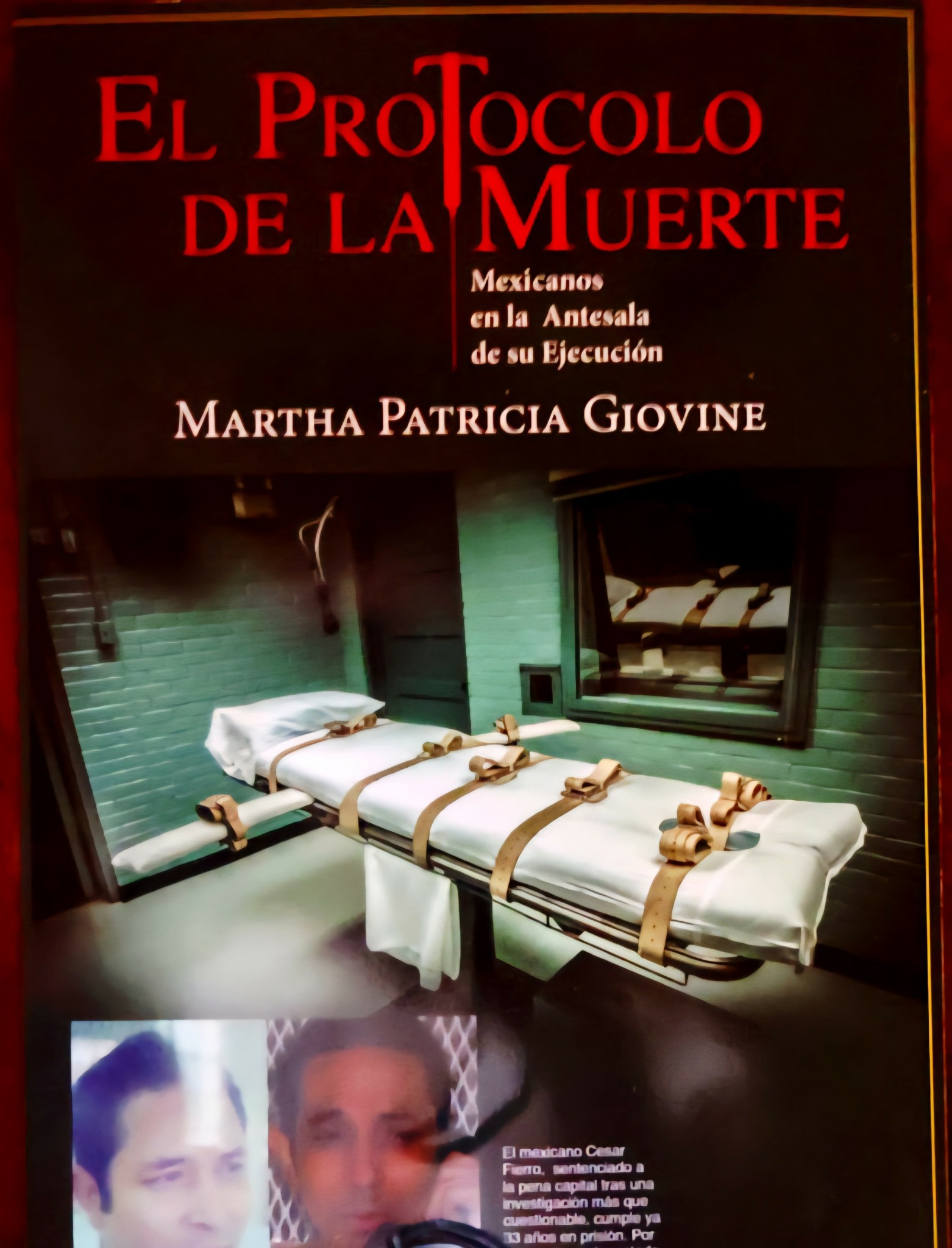

From there, I covered stories of immigrants fleeing violence and terror in their home countries, and I specialized in reporting on the death penalty in Texas. I attended an execution, interviewed men on death row and their families, and eventually wrote a book: El Protocolo de la Muerte: Mexicanos en la antesala de su ejecución (The Death Protocol: Mexicans on the Brink of Execution).

After decades in journalism, I was invited to work as an interpreter in immigration courts. It came naturally. I was familiarized with many of these stories; I had interviewed dozens of migrants. Some came seeking better lives for their families. Others were fleeing persecution, terrified, and seeking asylum in the United States.

Some might wonder whether being both a journalist and a translator or interpreter in immigration cases could create a conflict. In my experience, it does not. Journalism taught me the value of accuracy, ethics, and confidentiality—principles that are just as essential in interpretation and translation. In fact, interpreters and translators working in legal settings are bound by confidentiality clauses. Both roles are rooted in the same core values: discretion, integrity, and a commitment to truth.

As an interpreter, I became part of a very small group of people allowed into closed asylum hearings. But I wasn’t just observing—I was voicing every word, every pause, across languages.

Thanks to years in journalism, paired with a strong natural analytical capacity sharpened over time, I came to realize that many asylum cases are denied not only because of what the applicant says, but because of discrepancies between their testimony and the documents they submit as evidence. Judges aren’t reading the originals—they’re reading the English translations. And when those translations contain errors or contradict the testimony, the result is often a denial. Sometimes, the mistake lies in a poor translation. Other times, in the lack of proper certification.

That’s when I recognized the urgent need for professional translators who understand what’s at stake—who can produce faithful translations that preserve the original document’s meaning, context, and intent. Because sometimes, a translation can mean the difference between removal and refuge.

That’s how I joined Procertified Translations, a team of professionals committed to ethical, meticulous work. We pay close attention to detail—to the soul of a document—and to the story of persecution it may contain.

Today, I continue to write for the media, interpret in asylum hearings via video in courts across the United States, and translate the documents that asylum seekers submit in court. In many ways, I am my own firm.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I was born in Mexico City, where I lived until finishing high school. I earned a Bachelor’s degree in Communications from the Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, followed by a Master’s in Journalism and Translation from the University of Texas at El Paso. I’m naturally curious, analytical, and connect easily with people. Living in a binational region full of powerful stories—Ciudad Juárez and El Paso—journalism became a natural path for me. I started as a reporter and later built my career as an investigative journalist on the U.S.–Mexico border.

As a journalist, I tell stories that matter to the binational community. I strive to provide objective reporting and, like many journalists, to give voice to those who often go unheard. My work aims to expose systemic injustices. I try to go deeper, uncovering the layers beneath the surface. Some stories are always there—you just have to wait for the right moment to bring them into the public eye. I believe I connect easily with people; they open up to me, share their truths, and I take on the work of researching, verifying, and writing. I know how to recognize a story when there is one.

Eventually, I began working as an interpreter in immigration courts. Since hearings are conducted via video, I’ve had the opportunity to interpret in asylum hearings across nearly every state in the U.S. As an interpreter, I carry a deep sense of responsibility—because a poor interpretation can cost someone everything. I don’t just interpret words; I interpret meaning and essence. My deep knowledge of regional Latin American cultures allows me to provide both context and accuracy in interpretation.

Later, understanding the fundamental importance of translation in asylum cases—something many people often overlook—I joined a team of translators, many of whom also have immigration courtrooms experience or paralegal training. I began translating critical documents: personal declarations, responses in immigration applications such as the asylum form, and supporting evidence. Very few translators have this kind of firsthand knowledge. We are a small group who understand exactly how an immigration hearing works, what judges expect to see in a declaration or in the evidence, and how much weight they give to each translation.

I know that a single word can change the outcome of a case. I am detail-oriented. I try to understand the soul of the story and the weight of every word. I help organize the respondent’s narrative in a chronological and coherent way—without ever altering its content. I apply my knowledge of language variations across Latin America to ensure that each translation carries its proper cultural meaning. Once the translation is complete, I meet with the client and read the English version out loud in Spanish, giving them the opportunity to correct or clarify anything they deem important. I then certify the translation according to court standards.

Even though the three areas I work in—journalism, interpretation, and translation—may seem different, to me they are all the same: they are about telling stories.

How’d you build such a strong reputation within your market?

As a Translator

I’m known for accuracy and for preserving both the context and cultural nuance of every original narrative. I specialize in translating a wide range of documents, with a focus on asylum seekers’ declarations and supporting evidence submitted to U.S. immigration courts. I understand the relevance and importance of an accurate translation since I’ve been an interpreter during more than 1500 asylum hearings nationally.

As an Interpreter

Several immigration judges have remarked on the clarity and precision of my Spanish. I’m careful to preserve both tone and intent during interpretation. On one occasion, a federally certified interpreter—also certified in multiple states and a member of the National Association of Judiciary Interpreters—was observing one of my hearings. Afterward, she contacted me to ask where I had trained, commending my word choices and interpretation style.

What strengthened my reputation

What I believe helped build my reputation—whether in court, in the newsroom, or behind the scenes translating—is a combination of presence, precision, and perspective. I listen closely, and always try to understand what lies beneath the surface of each story or testimony. I don’t rush through my work. I stay with it until I’m sure the tone, meaning, and context are fully and faithfully captured. This habit of “staying with the story” has helped others trust my work and see me as someone who honors the weight of what is being told.

As a Journalist

I am known for being objective and for breaking exclusive stories in the newspapers and news agencies I’ve worked with. I could identify the deeper implications of daily events, often providing a new or unexplored angle.

One example:

When the State of Texas set an execution date for José Ernesto Medellín, a Mexican national, I immediately recalled that the International Court of Justice had issued an order requiring the U.S. to review his case—along with those of 51 other Mexican nationals—due to violations of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. I understood that carrying out his execution by lethal injection could trigger serious international repercussions.

Recognizing the significance, I formally requested a place as a witness of execution on behalf of EFE, the leading international Spanish-language news agency. Normally, only five journalists are admitted: one from The Huntsville Item (city where the executions take place), one from the Associated Press, and three from media outlets based in the city where the crime occurred. Since the crime had taken place in Houston and I was based in El Paso, I argued that if AP represented the English-speaking world, EFE represented the Spanish-speaking one. My request was granted.

I became the only journalist from a Hispanic media outlet to witness and report on the execution. My story was published internationally and I later was recognized by EFE’s Latin America editor-in-chief, both for securing access as a witness and the value of bearing witness in order to inform Spanish-speaking audiences.

A lighter example: A female lion at the El Paso Zoo killed the newest addition to the lion family. Local outlets treated it as just another animal death. But after interviewing zoo staff, I learned that the new lioness had attracted the male lion’s attention, which provoked the attack. I was collaborating with Reuters at the time, and I pitched the story with a new headline: “Lion in Love Triangle Kills Mate at Texas Zoo.” The bureau chief from the U.S. Southwest region called to tell me that my story was the most requested of the day by media outlets around the globe subscribed to Reuters.

Over the years, I’ve become one of the Hispanic journalists with the most in-depth experience covering Death Row cases in Texas. I reviewed court files, interviewed inmates and families, and published several stories on serious irregularities in capital cases—particularly the case of César Fierro, whose death sentence was eventually commuted. I’ve been interviewed by national media in Mexico as a subject-matter expert and wrote a book titled El Protocolo de la Muerte about my years covering this topic.

I’m also known for my strong commitment to confidentiality. This earned me the trust of sensitive sources. Once, after publishing a story based on a confidential tip, I was contacted by a law enforcement agency and asked to reveal my source. I refused, even when they threatened to subpoena me and warned I could be held in contempt to court. I stood my ground, and ultimately, I was not taken to court.

Some of my work was chosen as Best Feature Story and Best Interview of the Year by the Association of Journalists of Ciudad Juárez. I was also named Journalist of the Year by the Social Workers Association of El Paso and received the Ruben Salazar Award by the Mayach’en Museum and Cultural Plaza Project in El Paso, Texas.

Thanks to that trajectory, my stories have been published nationally and internationally in media outlets such as La Opinión (Los Angeles), Chicago Tribune, Miami Herald, El Nuevo Herald, El Diario de El Paso, El Paso Times, and La Prensa (New York); in Mexico by Proceso, La Jornada, Radio Fórmula, MVS Radio, Aristegui Noticias; and throughout Latin America and Spain in outlets such as El Mundo, El País, among many others.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

When I was covering death row cases in Texas, I dedicated over a year to investigating the case of César Fierro, a Mexican national sentenced to death based on a confession obtained under highly questionable circumstances. From the beginning, I knew the case had serious flaws—and I also knew it would require patience, courage, and long hours of research to tell the story responsibly.

I reviewed court transcripts, visited Fierro in prison several times, spoke with his family, his legal team, and pieced together a timeline that revealed disturbing inconsistencies. I did much of this while also covering other major stories and working on tight deadlines.

The case demanded emotional resilience as well. I had to sit with stories of injustice and despair; without letting them paralyze me. And I had to write about them clearly, without turning away from their human weight.

The series of articles I published helped amplify the conversation around Fierro’s case. Every time he had an execution date set, I wrote about the inconsistencies in his case, and the newspaper published those stories on the front page. Years later, his sentence was commuted. I wasn’t the only one working toward that outcome, but I never stopped believing that the story needed to be told. That experience reminded me that persistence, when grounded in purpose, is a form of strength; and that investigative journalism can, at times, help justice move forward.

Contact Info:

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Giovine.Martha.Patricia

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/martha-giovine-elpasotx-1405278/

Image Credits

Patricia Giovine. .