We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Mark Kline a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Mark, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you talk to us about how you learned to do what you do?

As far as writing goes, in a nutshell, I took a year’s writing course at a university, joined an online writers workshop, and dug in for the long haul.

The university course introduced me to some basic writing tools. Dialogue, fast narration, slow narration, pace, characterization, plotting. The writers workshop challenged me to understand and explain why specific things weren’t working in others’ writing, and it gave me a much-needed ego shock when I realized the problems others were pointing out in my writing were valid. It also led me to a few trusted critique partners and long-term friendships.

Looking back at my writing, for years I spent too much time revising stories, trying to improve/transform/save them instead of setting them aside and working on creating stories. I also wish I would earlier have been better at reading slowly and deeply, and of shifting focus and perspective when revising my writing, as is necessary in translating.

Mark, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

Some years ago my brother-in-law showed me an announcement for a short story contest, and I thought, why not? Surely it couldn’t be that difficult? It took about two minutes of staring at a sheet of paper to know that it most certainly could be. I ended up getting down something that was more of a rant than a story, yet creating a fictional world and moving characters around in it felt magical to me.

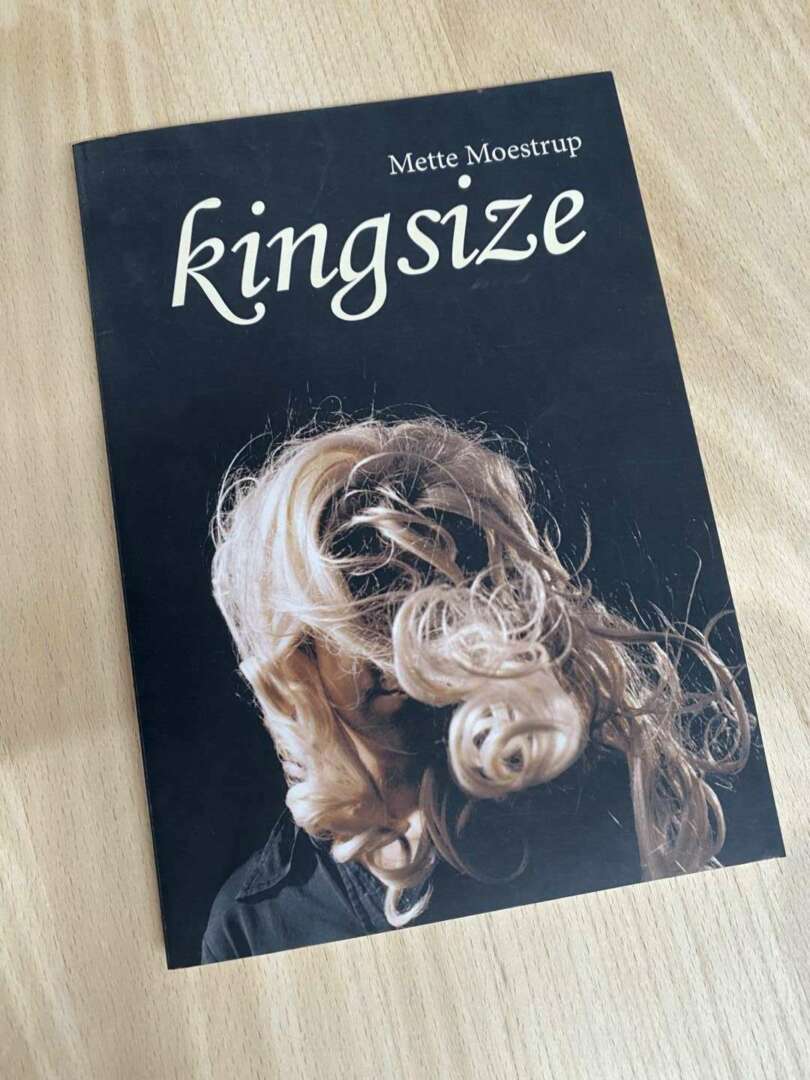

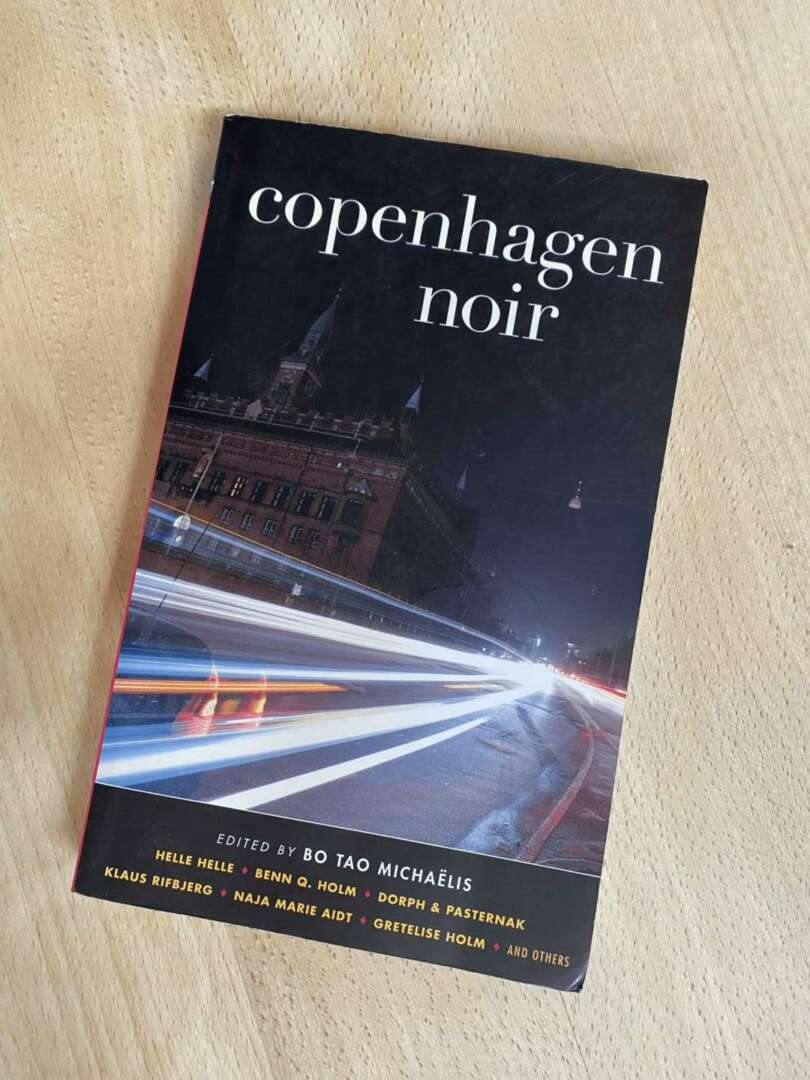

After having some stories accepted in literary magazines, and since I’d been living in Copenhagen, Denmark for about twenty years, I thought it would be interesting to try my hand at translating. I started by reading translations closely and comparing them to the original in Danish, and by reading about translation in general. I found that many of the pleasures of writing, such as the nuts-and-bolts stuff like shaping sentences and paragraphs, finding just the right word or phrase, are the same in translation, but with an added dimension: searching for the tone, voice, style created by the Danish writer. There’s a bit of a 3D-crossword-puzzle feel to it..

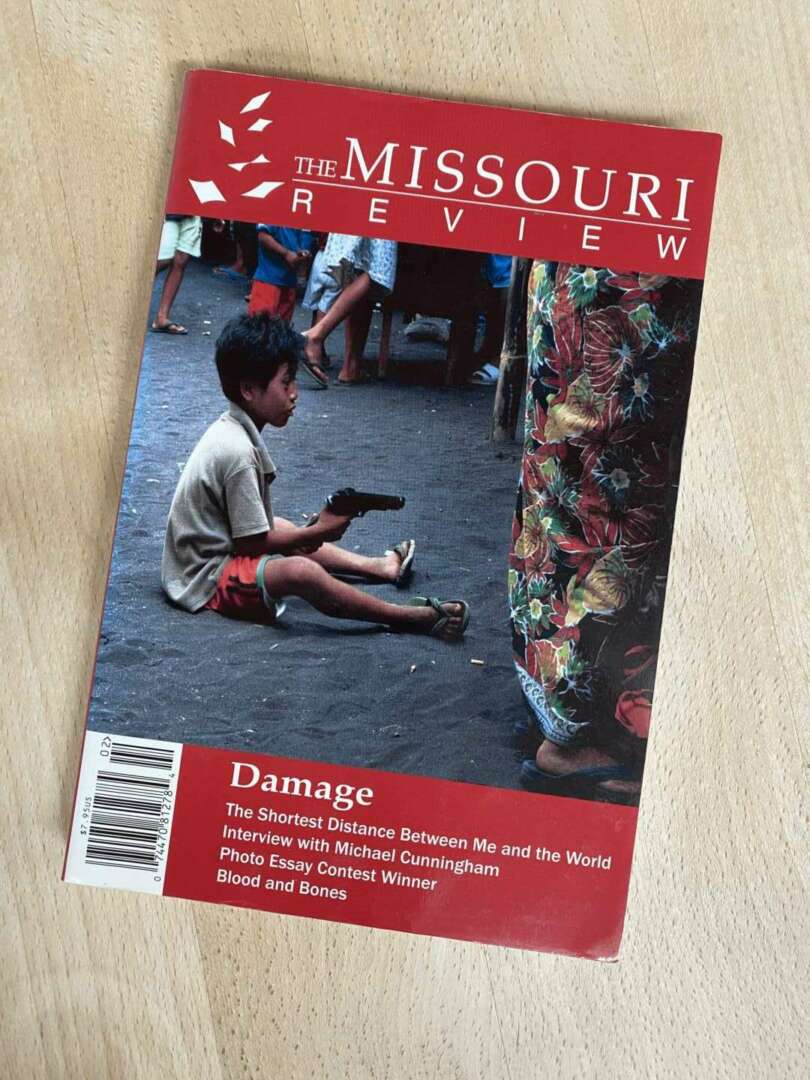

Though I like translating a variety of works, including novels, poetry, short stories, essays, speeches, and books by psychologists and journalists, many years ago I decided to specialize in translating Danish crime fiction, which has long been popular abroad. At present I’m at fifteen crime novels and counting. This has given me a familiarity with various aspects of the genre that crop up again and again.

I’ve been so busy translating the past many years that writing short stories has taken a backseat; there are only so many hours a day I can spend spitting out words onto a laptop screen. But I write during lulls in translating. It’s gratifying when a magazine accepts one of my stories, definitely, or when a book I’ve translated comes out. It’s the process, though, that gives the most immediate satisfaction. And frustration, foggy-mindedness, agony. Once in a while I question if it’s all worth it. Then I start thinking about that guy in a tailored suit I noticed a while back, his linen napkin tucked in, eating in a rowdy college bar. Or the offhand remark someone made thirty years ago about my grandmother. Writing fiction is a crazy way to twist the world into making sense.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

It’s so difficult to call any single part of translating and writing the most rewarding, because there are so many. To name a few: collaboration with writers, getting deep into the flow of writing, and having something I love to do – reading – as a necessary part of the work. But when I step back and consider everything about the past many years, it’s clear what the best long-term reward has been: how perfect the work has been for both me and my family. Besides being exactly what I wanted to do, it’s given us a great deal of flexibility in our daily lives, which eliminated a lot of stress. I can’t come up with any work that would have been better for us.

How about pivoting – can you share the story of a time you’ve had to pivot?

I realized soon after I began writing fiction that I would have to deliberately abandon notions forged in school, such as writing grammatically correct, with proper punctuation. The short stories and voices and characters that were coming to me needed an open mind, a starting point outside the confines of correctness, otherwise they would never make it to the page. It felt right to do a lot of “wrong,” to use things such as colloquial dialogue, fragments, stream-of-consciousness writing, and unruly first-person narrators. There was more to it, though, than grammar-related issues. I had to learn to let go and find a route to that open mind. Pacing back and forth and around the yard helped, Reading bits of certain writers’ stories.

It’s the same with translation. You have to open up to all the elements of a text and echo them, mirror them, however you want to characterize what translation does. You have to learn endless ways of expressing the incorrect and be comfortable with them. It’s a challenge. Try writing a three-page sentence, for example.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://markwkline.com

Image Credits

Poul Lange

Berit Lange