Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Marianne Connolly. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Marianne, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you open up about a risk you’ve taken – what it was like taking that risk, why you took the risk and how it turned out?

I grew up in the sixties and came of age in the seventies. My late teens and early twenties where a time of risk taking. I skydived, moved alone to a new city, hitchhiked, got mystical, stowed away on a ferry, tried every new food offered to me, and had my heart broken again and again. In the eighties I lived in Boston, wrote poetry and—here’s another risk—read my poetry in front of audiences, later calling it performance art.

But the two greatest risks of my life have to do with slowing down, digging for the stillness under impulse—burrowing under my preconceptions, perfectionism, and my long list of “shoulds,” to discover my authentic, creative work. Both acceptance and change can involve risk.

In 1985, after years of being invested in the identity of being a Writer, I found myself alone at my desk: miserable, lonely, and crushed by my own perfectionism. My father had always said I was a poet. When I struggled in math, he said, “That’s just because you have a poet’s mind.” Being a poet made up for my geekiness, queerness, and blatant neurodiversity. It was my salvation. Nobody mentioned the empty room and the even emptier ream of paper. If being a writer was my identity, if this made up for math class, gym class, and Mrs. Duggan keeping me after school every day —then it needed to be perfect.

As Anne Lamott writes, “Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor.” She says it will keep you crazy and cramped your entire life. I read her book later, but in 1985, I was struggling, and began getting migraines every afternoon, right before my writing time.

One day a friend brought modeling dough to our monthly support group. Sitting with six other women, I complained about my crazy and cramped unhappiness as I made a teeny tiny tableau for teeny tiny clay characters. It’s almost impossible to be a perfectionist with Play-Doh. Towards the end of the meeting, someone said, “Why don’t you go to art school, Marianne? Let go of writing for a while.”

Nobody had ever told me to be an artist, including my support group. They just said—go to art school! Make weird stuff. Play with materials instead of staring at a blank page. So, I put together an imperfect portfolio and took a risk. I went to art school. A few years later I had an MFA in visual art, and I had grown to love creative work again.

All creative work involves risk. Visual art in the nineties involved experimentation, self-exposure, and the pressure to push ourselves to the limit. One risk for me was finding a less “heroic” method of working, and I began to work small, creating page-sized pieces rather than room-sized installations. Also, I took the risk of putting life first. Birthing my daughter, raising her, and surviving two debilitating illness taught me to listen to life, and to be a creator without harming my health. By necessity, my materials and methods have changed over time, and all of this has brought me back to a love of writing. I’m coming back to language with an understanding of process—creation not perfection.

Marianne, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

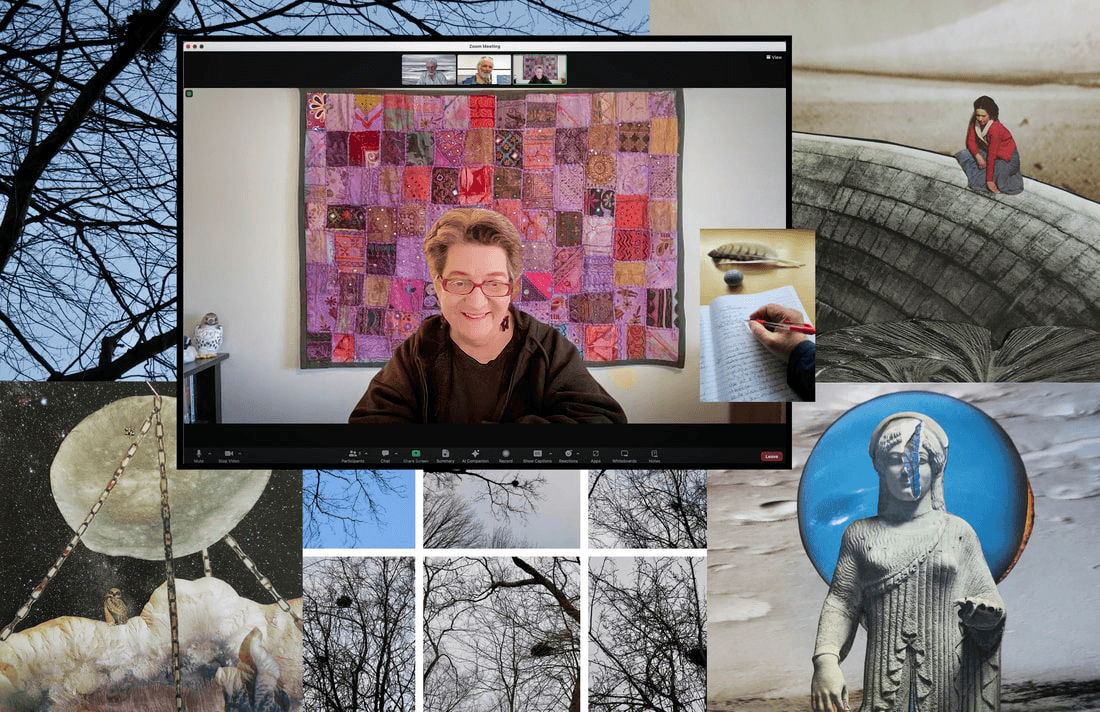

For two decades I’ve been a member of Gallery A3, an artist-run cooperative in Amherst, MA. As my share of the cooperative’s work, I’m the digital coordinator, and I do the website, social media, and the monthly Art Forums on Zoom. My job is to bring the work shown in the interior of the gallery to the outside world. I believe in artists helping other artists, and in making work accessible to as many people as possible. Visibility helps us sell our work—and sales help artists continue to create—and at the same time a digital presence allows the larger public to see the work, interact with the artists, and join the creative discussion, whether or not they are able to purchase art.

As a gallery member, I’m most proud of our Art Forum series. I love unpretentious and nonjudgemental discussions about artmaking. I want to talk about everything from materials to emotions to inspirations to real-life challenges.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

Sometimes, resilience is what happens when you have no other choices. A bad thing happens—a trauma or an illness—and we need resilience in order to keep moving. Creativity helps us practice resilience, developing flexibility so our scars don’t make us immobile.

About six years ago I suffered a critical illness and then a mild stroke. It changed everything. My body came back to me one function at a time—breath, thought, speech, movement. Finally, one day I could write again! Although I still have trouble with coordination and reading, I continue to recover. In my experience, the practice of creativity helped me face an enormous challenge with resilience.

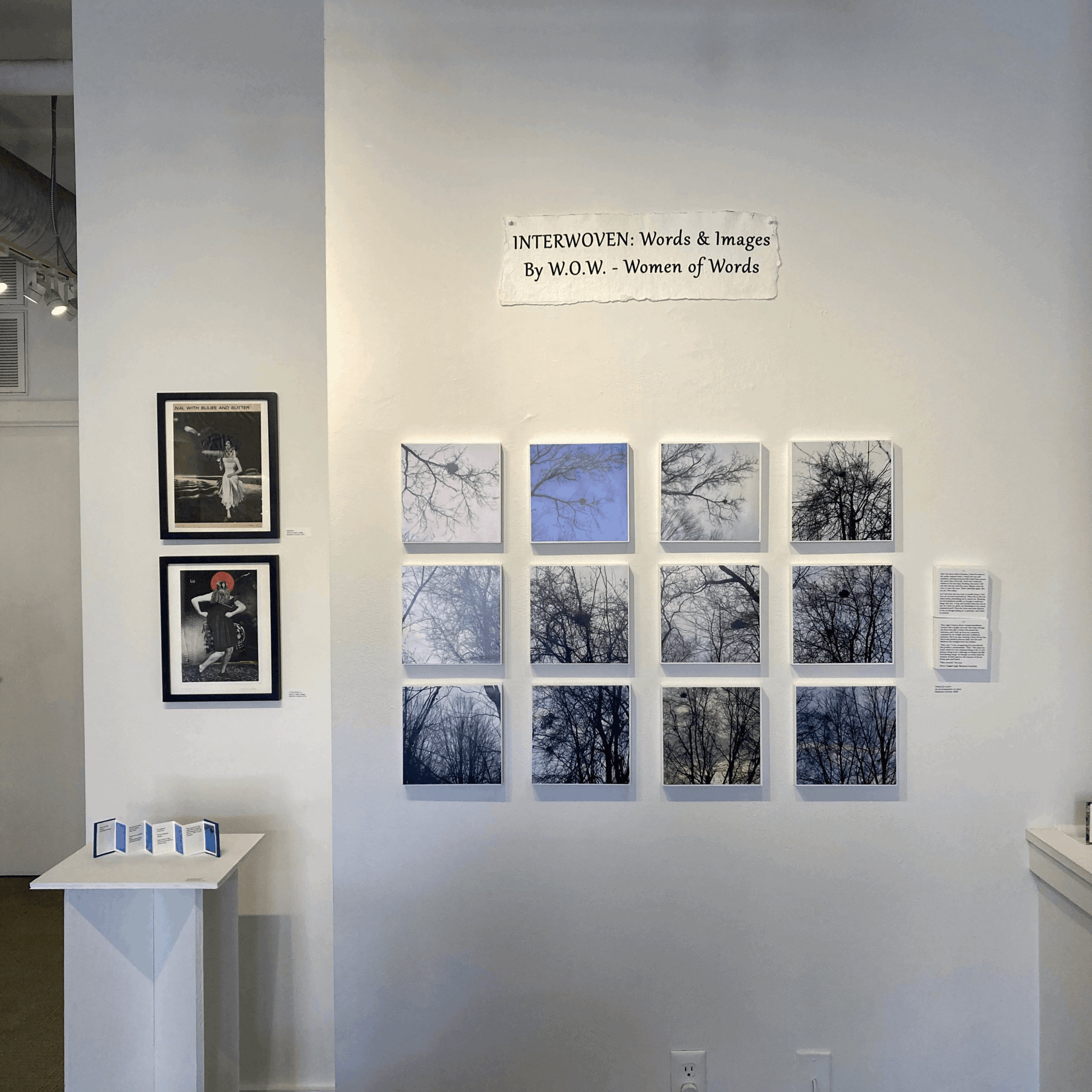

You asked a question earlier—what are you most proud of? I’m proud that I continue to create. Although partially disabled, and dealing with cognitive differences, I find new ways to work. Creativity is like water—it’s like being in motion—and it’s an essential part of my life. Lately I’ve worked on several collaborations with other artists and turned a planned solo exhibition into a group show. This is part of staying in motion.

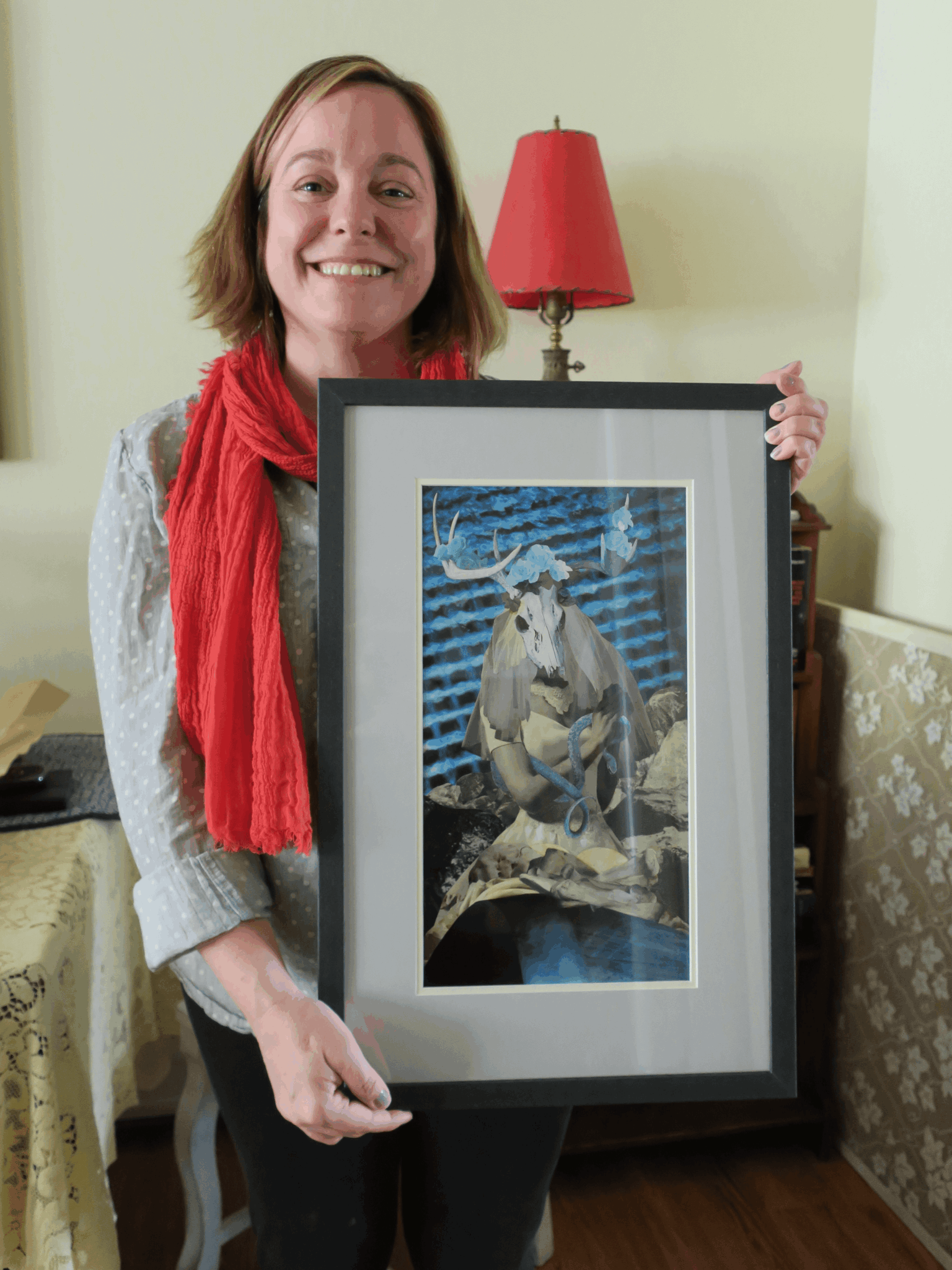

About my own visual art: my small paper collages are completely analogue; I cut and past by hand. My current series involves were-people and shape-shifters, inspired by and inspiring my short fantasy stories.

What’s a lesson you had to unlearn and what’s the backstory?

Returning to the theme of perfectionism—perfectionism is something I will have to unlearn again and again. I make hand-cut paper collages, and I enjoy the fussy detail, but I also need to shake myself up and learn to experiment, to get messy. Nothing is done until we call it done, and every step of the process of creation is valuable. But sometimes the process is fragile. Negatively criticizing a work in progress can take the life out of the work. So, I try to turn off the inner critic until the work is finished. It’s hard work, but the more I put that bossy critic in its place, the easier it gets.

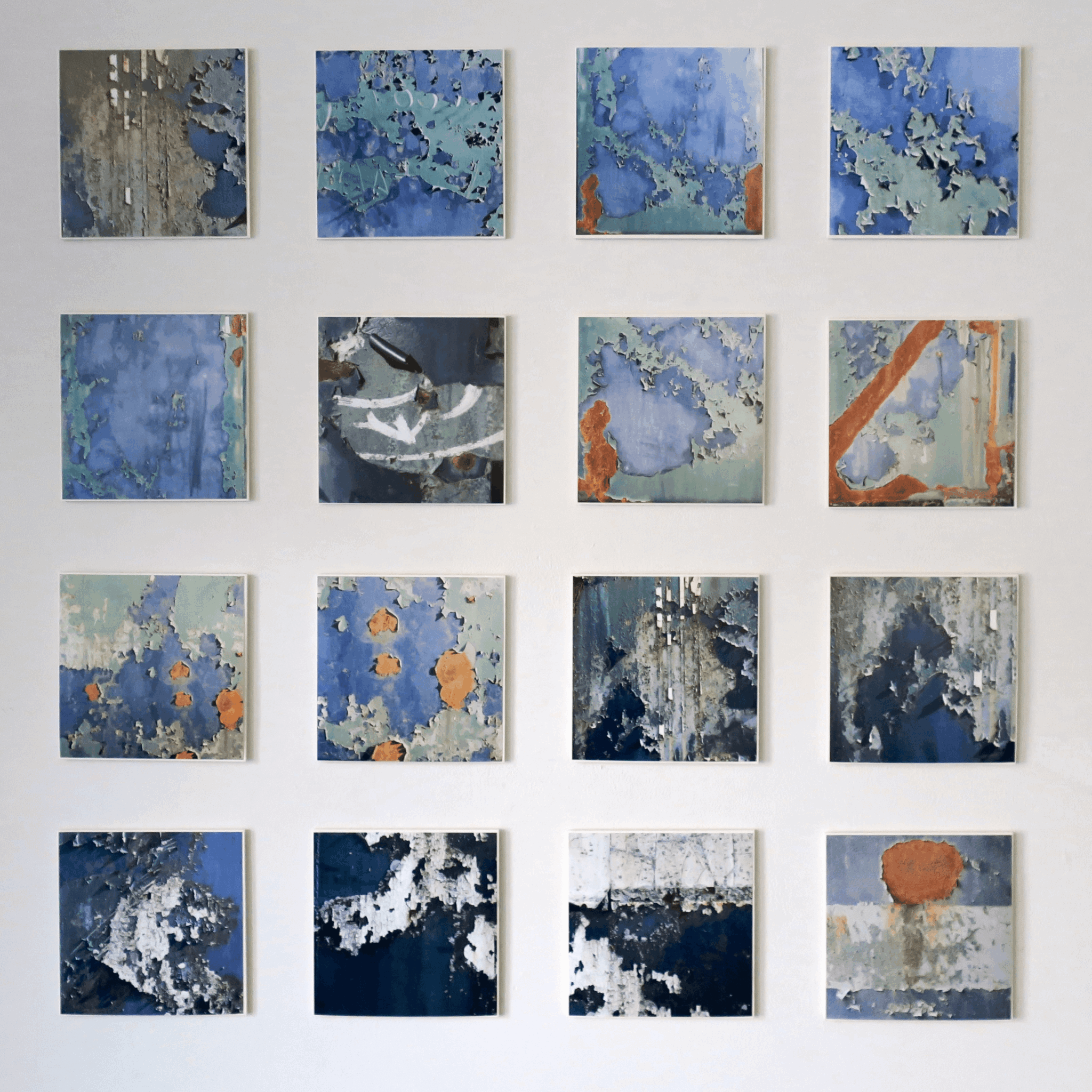

I once had a box of photography mistakes, test prints from doing some darkroom printing. I’d put all the rejects in a box and saved them for a few years. One day I was thinking about perfectionism and reworking mistakes, and I took out the box of rejects. I cut them into strips with a paper cutter and wove the strips together. The discarded test prints took on a whole new life as a series of photocollages.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.marianneconnolly.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/marianne.connolly

- Other: My cooperative gallery, Gallery A3: https://www.gallerya3.com/

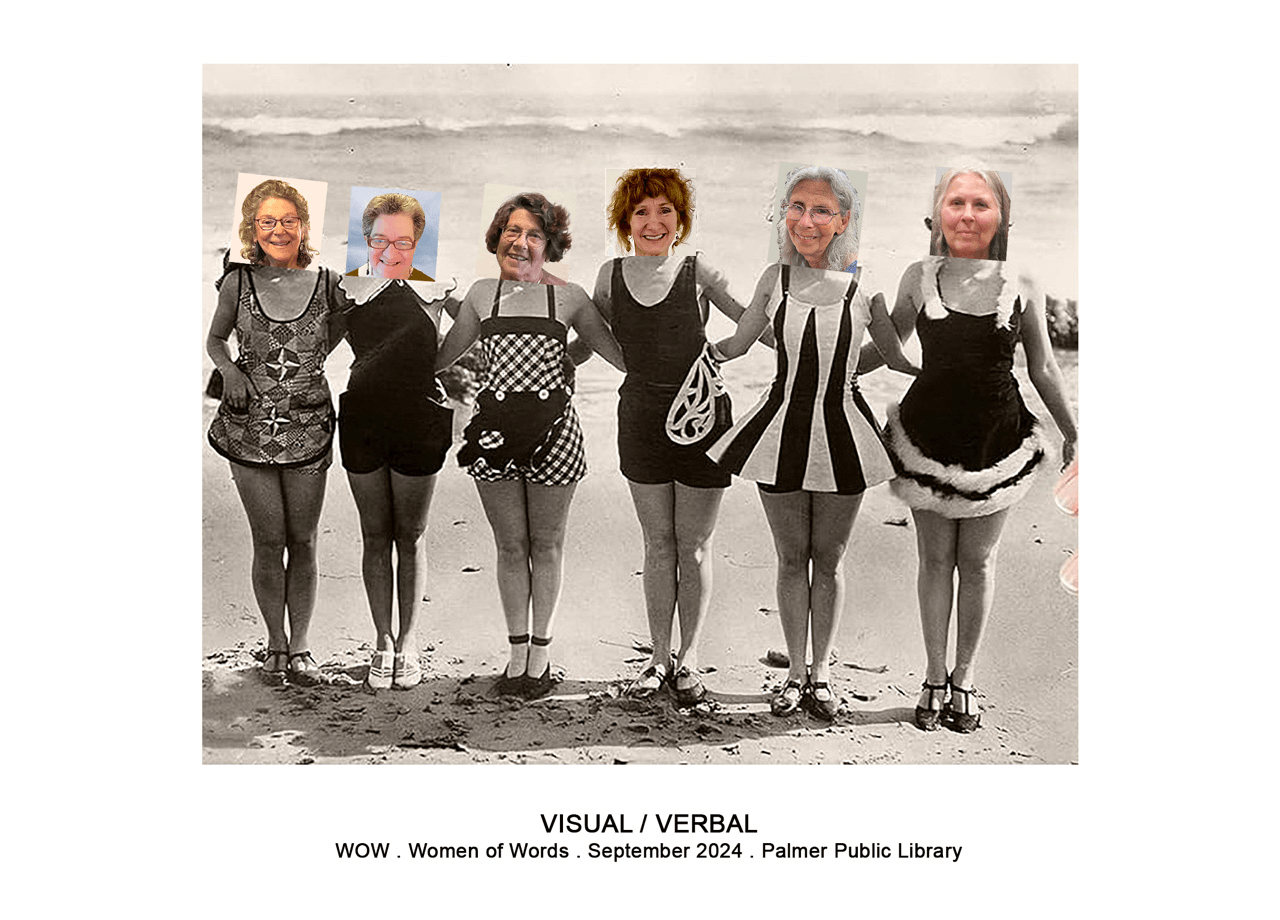

My upcoming show is part of Women of Words: https://womenofwords.myportfolio.com/september-2024

My writing name, Marianne Xenos: https://mariannexenos.com/

Image Credits

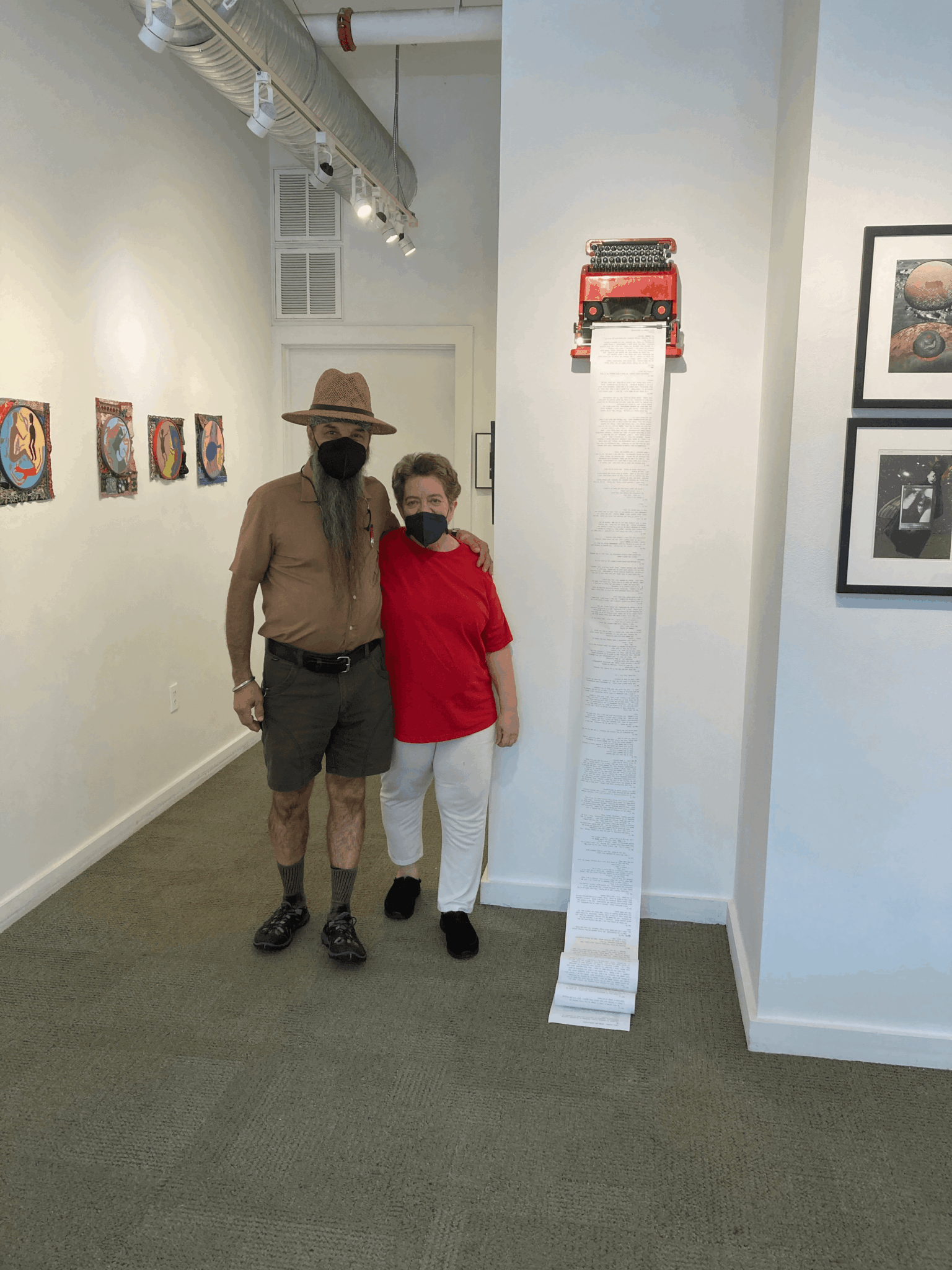

1. Photograph and photocollage by Larry Rankin.

2. Postcard design by Sue Katz

3. Photograph by Gene Butera

4. Photograph by Marianne Connolly

5. Photograph by Marianne Connolly

6. Photograph by Marianne Connolly

7. Photograph by Tracy Marian

8. Photograph by Marianne Connolly