Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Margie Stevens. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Hi Margie, thanks for joining us today. Can you share a story with us from back when you were an intern or apprentice? Maybe it’s a story that illustrates an important lesson you learned or maybe it’s a just a story that makes you laugh (or cry)?

When I first started volunteering at the mobile unit of Challenges Inc., I quickly realized that all of my clinical education regarding drug use was almost useless. I had to learn a new language. I often laugh and say that distributing sterile drug use supplies is a lot like ordering a pizza; you have to understand what the toppings are. For instance, when a participant walks up to the bus and says they need the works, they mean they need syringes, cookers, cottons, alcohol swabs, tourniquets, and Narcan/naloxone. A common response to the participant’s order would be would you like condoms with that and/or when’s the last time you’ve been tested for HIV or HCV? I also didn’t understand some of the lingo, such as shooting clear (crystal meth), which makes a difference in regards to the kind of sterile drug use supply the person needs. The participants have taught me so much about the drugs they use and why they use them.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

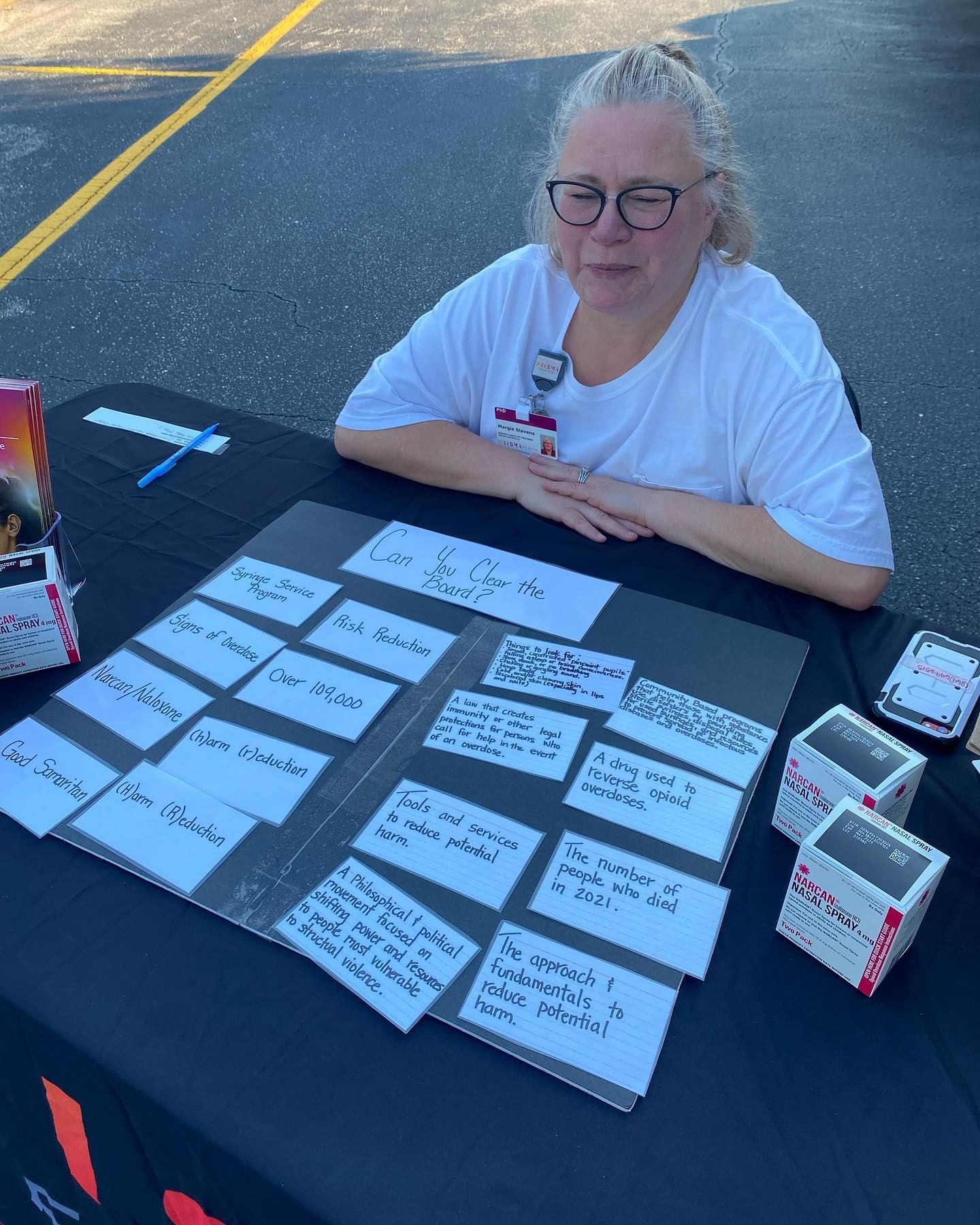

Almost 20 years ago, when I was completing my Rehabilitation Counseling Master’s degree at the University of Memphis, I was taking an Alcohol and Drug class, and I wouldn’t say I liked it. I thought I would never work with “those” people, meaning people with substance use disorders. Little did I know that would become the population I am most passionate about helping. Then, one day, a colleague asked me why I lacked the desire to help and advocate for people who use drugs. I replied by stating, “I can’t relate to that population. I have never used drugs.” My colleague then asked, “Oh, do you have a friend or family member who is blind or deaf? After all, you have been learning American Sign Language and reading Braille. You also do a lot of advocating for people who use wheelchairs and use assisted technology. Do you have a friend or family member who has any of those physical disabilities? What makes these individuals so relatable to you?” The answer to those questions was, “No, I don’t have a friend or family member with any of those disabilities.” It was then that I realized that my implicit biases and lack of interaction with people with substance use disorder provided a very fertile ground for a stigmatized mindset toward not only the field of addiction medicine but also toward people who use drugs in general. I also realized that you can read about statistics about an illness or disability, but that does not provide you with the “root cause” or lived experiences related to that illness or disability. After getting my Master’s degree, I got my PhD in Educational and Psychological Research with a certificate in qualitative studies. Qualitative research allowed me to hear the voices of populations that are often stigmatized, which made me more compassionate and understanding about people living with substance use disorder. Today, I am an assistant professor at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine-Greenville, where I teach medical students about substance use disorders and treatment. In every lecture I teach, I make sure to include the voices of individuals living with substance use disorder or who use drugs. Our students are brilliant, and they understand what happens at the mu receptor when a person uses heroin. Still, textbooks never explain how that person ended up using heroin to begin with. Hearing those stories from individuals has made students much more compassionate healthcare providers. In addition to being an assistant professor at the medical school, I am the educational and mentoring director at the Prisma Health Addiction Medicine Center, where I mentor students in addiction research and provide addiction education to others in healthcare and the community. And finally, I am a volunteer harm reductionist with Challenges Inc., Harm Reduction Services, Upstate South Carolina. I distribute harm reduction supplies (this includes syringes, safe drug use supplies, naloxone/Narcan, and condoms) and education at the Challenges Inc. mobile unit and also do a lot of community education to reduce stigma toward people who use drugs and harm reduction services.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

This is embarrassing, but it wasn’t until 2019 that I learned what harm reduction was. I was teaching medical students that opioid use disorder is a chronic brain disorder. I was teaching them what happens and how sick a person gets when they withdraw from opioids. That’s when I met Marc Burrows, the founder of Challenges Inc. Harm Reduction Services. During our conversation, he told me he gave people who use opioids and other drugs sterile syringes and sterile drug use supplies. Like so many others, my first thought was, I don’t want to enable drug use! Then he posed the question, “Do you think a person who uses drugs is just not going to use drugs because they don’t have access to sterile supplies?” That’s when I realized my ignorance and hypocrisy. I teach medical students about how sick people get when they are addicted to opioids and start going through withdrawal; this is also known as “dope sick” because the person can get very sick until they can get more opioids, “dope,” in their system. That was the lightbulb moment for me. I knew that people who were addicted would use drugs by any means necessary to stop that awful withdrawal feeling, even if it meant they had to share a syringe or reuse a syringe. Harm reduction is the beginning of the continuum of care for people who use drugs. Harm reduction reduces the spread of diseases such as HIV and Hepatitis C. And statistically, people who engage in harm reduction services are five times more likely to enter recovery than those who do not receive those services. It also provides people who use drugs with a community of people who treat them with compassion and dignity. Another thing I had to unlearn was the idea that everyone who uses drugs has an addiction. Many people use drugs and/or drink alcohol without having a substance use disorder. But since alcohol is legalized and drug use is not, drug use is demonized more often than alcohol. However, people who drink alcohol have access to a safe and regulated supply. People who use drugs never know exactly what they are getting and oftentimes don’t have access to safe and sterile drug use supplies such as syringes and drug testing supplies.

Putting training and knowledge aside, what else do you think really matters in terms of succeeding in your field?

Educate. Educate. Educate. And compassion! I only know that in the grand scheme of things, I know nothing. I am continually educating myself. I also know that I am not the only person out there who needs to learn about addiction and harm reduction, so I educate the general community and people who work in the healthcare field, basically anyone that I run into. They always say it takes a village to raise a child. I say it also takes a village to keep them alive. Everyone is someone’s child, and with the continued rise of drug overdose, everyone needs to have a better understanding of what addiction is and how they can help. We have to reduce the stigma toward people who use drugs and harm reduction. Everyone needs to have naloxone/Narcan and know how to reverse an overdose. We need to rally all of our churches to help in non-judgemental ways and be compassionate toward their brothers and sisters who use drugs. We also have to educate people who use drugs on how to use drugs safely.