We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Maren Curtis. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Maren below.

Maren, appreciate you joining us today. It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

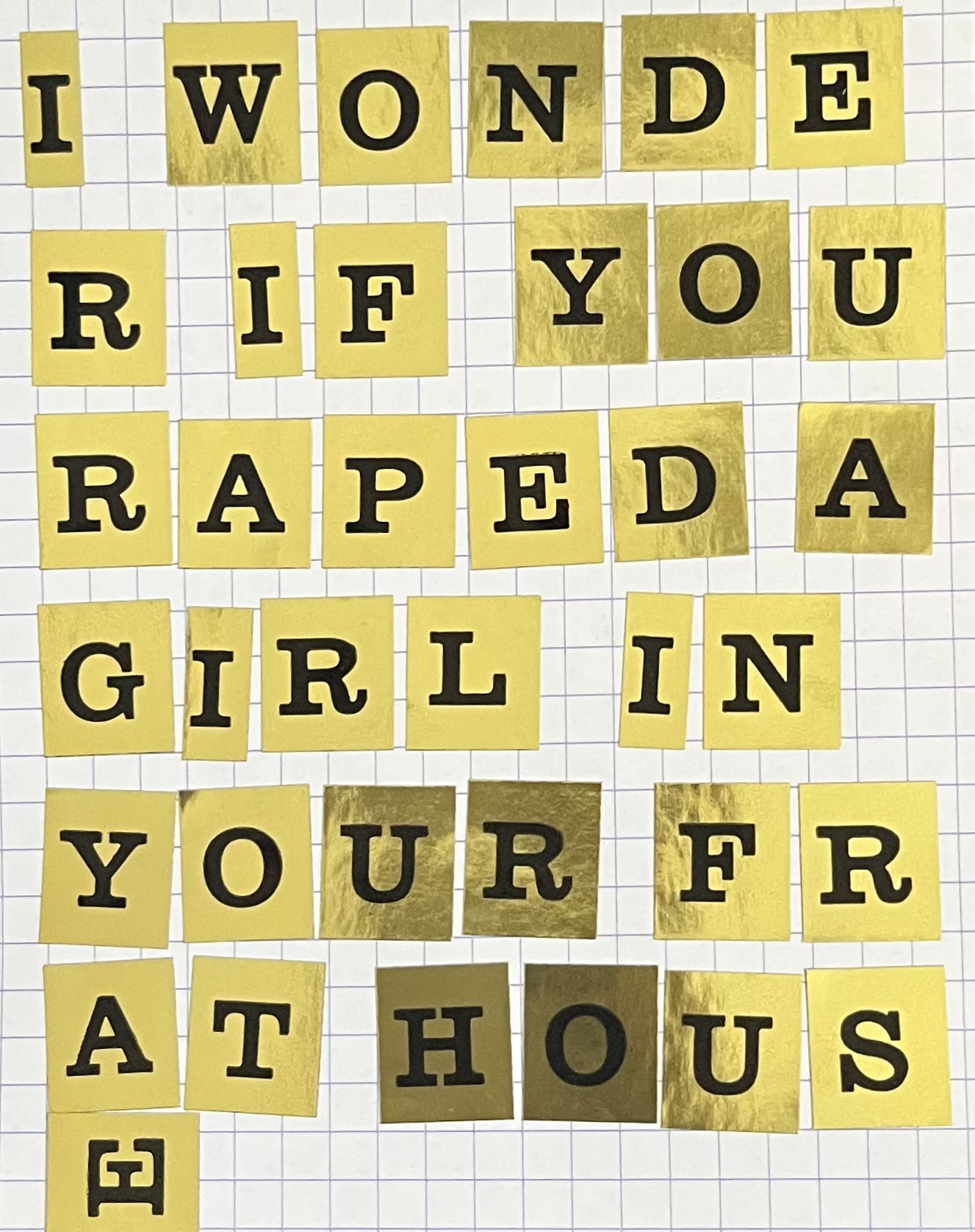

I was raped two months into my freshman year at CU Boulder. How it happened, where it happened, and with who made it clear to me that coming forward wouldn’t be safe, so like many victims I repressed. Though we can try, there is no way to eliminate the memory of sexual violence from our bodies, even if we push it out of our minds. I lacked a support system and was surrounded by a rape culture that thrived off fear and secret keeping. Much later I’d discover most of the women I’d known had been raped or assaulted at one point or another, often at a party just as I had been. I don’t know anyone who went to the police, we all knew the depth of their ineffectiveness and their connections to rape myths and the Greek system that dominated the school’s social rules.

Years passed before I could admit to myself that I had been taken advantage of. I was deeply ashamed that I’d been drinking so heavily. When I was taken, unable to support my own weight from the party full of people I knew, I was terrified no one would believe me. There were many points where intervention should have taken place. Prior to my assault I’d assumed my friends would never let anything happen to me in front of their own eyes, but I was proven wrong. It planted a two seeds in my mind, one that I had never been raped at all because if I had someone would have helped me. The other said I wasn’t helped because I was asking for it. I was inconveniencing my peers’ fun, which was more selfish than expecting mutual protections. Either way, I had no intention of coming forward.

The rest of my time in Boulder would consist of hiding. If I tried to go out, I would see my rapist. There was no attempt to go places he wouldn’t be, so I stayed home. The stress and isolation caused me to approach a break with reality. PTSD consumed my life, for years my cortisol was so high, I fried my immune system. I developed or worsened four chronic illnesses; diseases I will be managing with surgeries and medications for the rest of my life. My anger and my paranoia were once again incompatible with the fun that had to be perpetually maintained in order to fit into the social order of the school. My cries for help were met with awkward silences, bullying, abuses, and stern conversations requesting I stop talking about my grievances in the presence of others. As it was stated, there’s a time and a place for negative conversation, and it’s not when everyone is trying to have a good time – which was all the time. Ignorance and hegemony ran the game.

I made work about my experience in undergrad, but it was very tame considering my fear of retaliation. I knew if I gave away too many details, a whole fraternity would be after me, along with all the women who associated closely with my rapist. That all changed when I got to RISD.

I applied to grad school in my senior year hoping to start life over again. I had spent the last four years in a frozen state. I felt like I was living a half life, trapped between maintaining my will to live and my lack of mobility. I wanted to go somewhere completely alone. I wanted to make my art and do nothing but that, and when I got into RISD, I finally saw a light at the end of the tunnel.

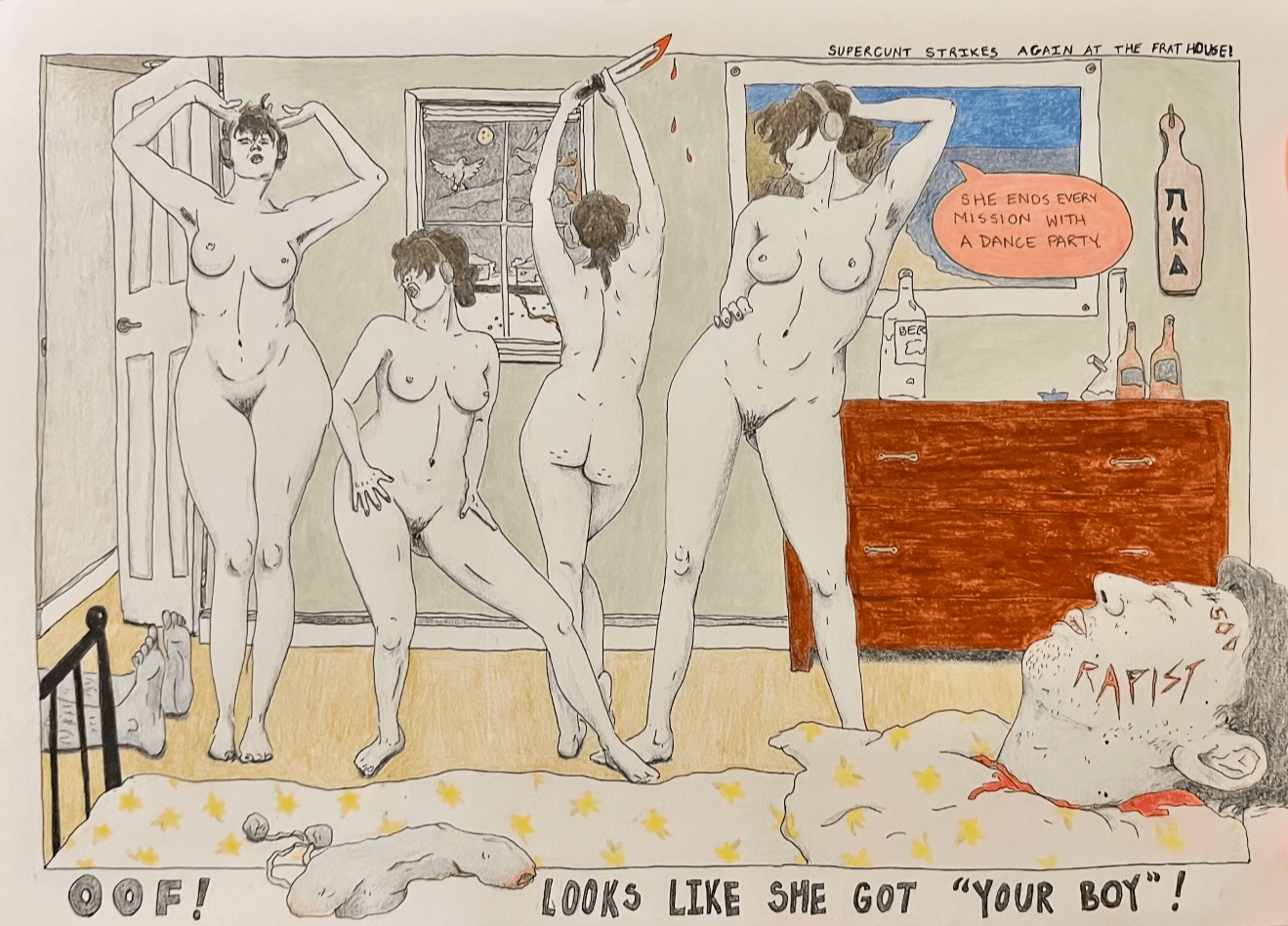

My cohort was entirely female, largely international, and extremely political. The friends I made completely changed the way I looked at Boulder, and validated my anger. I was finally able to look at those years I thought would never end retrospectively, and in my second year my work changed from a perspective of fear to a perspective of rage.

In September of my second year, I released an essay, the most candid I’d ever written, about my assault and the ousting that ensued later. The website, originally named killyourrapist.net and now named survivorsartsandwritingcollective.com, is an open submission arts and writing space dedicated to unrestricted, uncensored, safely anonymous work for other survivors to share. The day I released was probably the scariest day of my life. I didn’t know what the reaction would be, not only from my followers and peers but from my family and classmates. To my surprise, my life would completely change within hours.

Hundreds of women and men reached out, many whom I’d known my whole life, repeating my story back to me. Girls from Boulder saying they’d experienced the same series of events, down to the community repression and self isolation. Girls who had never heard their experience reflected so literally, and most importantly girls who thought they were alone in their struggle. I myself had no idea how unoriginal my story was. It was liberating and enraging how much I related to these girls. It made me realize how little I’d been given, how preventable it all was, how betrayed I’d been. If I had only known, would I be sick? What would college have looked like for me? How much shorter would my recovery had been? Would the culture of silence exist at all if women were actually able to talk to each other? My only wish was that I’d had something like it when I was eighteen. I was angry like I’d always been, but now I was unafraid, too. My work would never be the same.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I grew up in the Bay Area, but my whole family is from the Midwest. I was raised in a strict household and my parents expected my twin sister and I to be personable and kind. We ate dinner as a family every night, technology and television were privileges not rights, and respect for my parents’ authority was without question. My parents are very realistic people. They both had difficult upbringings and escaped the lives they loathed. Both of them are extremely hard workers, uncompromising in their beliefs, and put my sister and I before anything else. None of our house rules were without reason, and though we had a year or two of standoffs when I was a teenager, my parents are my best friends.

I am just like my Mom which means two things. One, I am extremely strong willed and stubborn. Two, I have an authority issue. My parents were unique in what guard rails they chose. My sister and I had a strict curfew we wouldn’t dare to stray from, but considering the substance ridden community we grew up in, they were candid with us about drinking, sex, and drugs. They both felt strongly that denying reality was not a way to prevent trouble, rather it fed the fire. From the age of fourteen I was required to have a job, play sports, and do my best in school. I was a terrible math student, numbers have always gone right over my head no matter how hard I tried. They wanted my sister and I to do well in school as they had not, but as long as we tried hard, the grade didn’t matter. I always wanted to be an artist and I was always supported in pursuing it, though they had their anxieties about me being unemployable. The list goes on, but overall, they just wanted my sister and I to be ready for the real world and all the good and bad it brings.

My Mom was concerned about sexual assault. She wanted us to understand our limits with alcohol before we went to college to avoid us losing control of ourselves. She wanted us to surround ourselves with friends that were mutually concerned with each other and in Marin, we had an incredible community. She made no attempt to deny the fact that at fraternity parties, we were going to be targets. She did everything she could to prepare us.

My tolerance for alcohol was much lower at altitude, and Boulder is a mile high. The night I was raped, I blacked out. It was the first time I’d ever been so drunk, and I was immediately punished for it. When I told my Mom and Dad what happened to me years later, and even more so when I released my essay, it devastated my Mom. There’s only so much you can do to protect your child, and even though I was as equipped as I could have been, there is no stopping a predator from preying.

There are works I have made that make my parents extremely uncomfortable, but they rarely try to dissuade me from making them. They know I won’t let their opinion dictate what I produce either way, but they talk to me openly about my work. I know most people would never be able to talk about rape and violence with their family’s support, so I let that raise the bar for how open I’m willing to be. My childhood and relationship with my parents is reflected very clearly in my tone and barefaced writing.

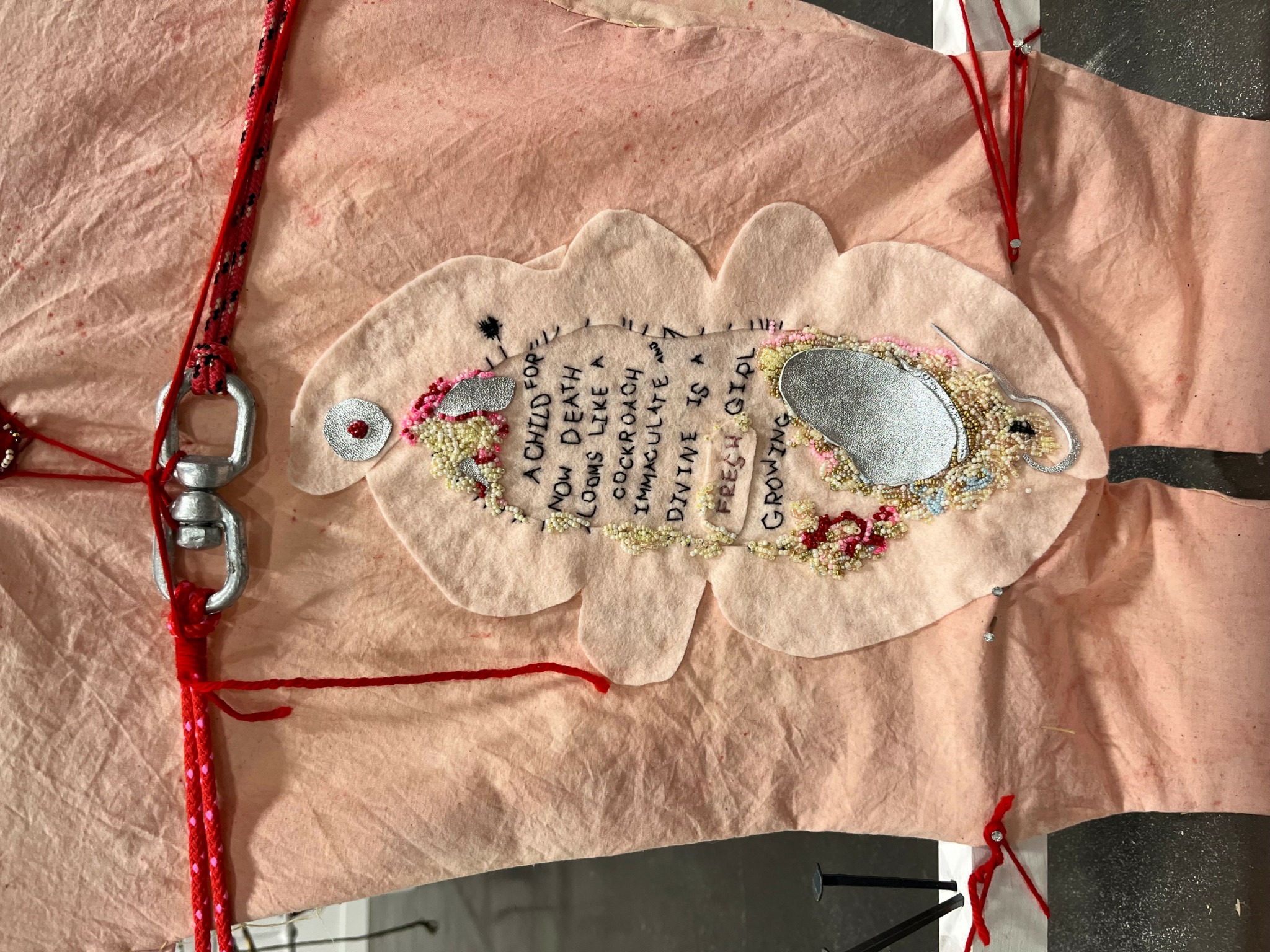

My work is of me, but it is not meant for me. I don’t feel comfortable drawing other women’s bodies, even if they asked me to because the bodies in my work are almost never in an empowered position. They are receiving violence far more than they are giving it. There is a reality to the destruction of my form that I can’t separate myself from, especially as I have become ill. Thus, I have become well acquainted with the body I live in, and I’m most proud of the aging element of my portraits. I can watch myself age, both mind and body. I can see my relationship to my surroundings and emotions fluctuate, I can watch my literacy expand and my perspective radicalize. Anyone can see my work in this totality. There is never a beginning in end, instead it records time. Survivors can see me after the hard years and they can see me in them. They can watch me full of fear and they can watch me full of rage. They can see an arc of change and hopefully they can see a happier end for themselves. Hopefully they can see none of it is permanent.

My work is about labor. I have been fascinated with painful processes since I was a teenager. Stippling, hand sewing, natural dyeing, hand spinning yarn, and anything else that requires months of attention. It gives me a physical relationship with the work, I am entirely against digital media. The work only works if I’m in it. The quilt I made for my thesis at RISD took an entire year. I worked on the floor of my apartment, the whole floor as it was a studio, and quite literally rolled out of bed and worked until I fell asleep. It was a labor of thousands of hours, a year of change and commitment. I’m a few months out from its completion and I’ll admit I’ve been struggling to make anything new. I put my body into the process and I have to find my practice all over again to endeavor on something new. It is not just the product of time but the product of obsession. It is the physical proof of a thought, of the longevity of trauma. In a world where there is a limit to how long you can feel, the quilt completely denies it.

Have any books or other resources had a big impact on you?

I love critical essay, for the most part I read nonfiction. My most notable exception is Toni Morrison, every single book. It’s not that I dislike fiction. In fact, I think sometimes I learn more from a constructed world than I do from the reflection of our own. But Toni Morrison changed how I look at atmosphere, magic, and intuitive knowing. Her ability to create a network of characters whose minds are all available to us in completion. Her ability to place us behind the eyes of the child and the pedophile in The Bluest Eye, or the breath of the town in Sula, where flowers grow or die in the presence of evil. The way the island listens and butterflies gossip in Tar Baby and the complexity of Milkman and Guitar in Song of Solomon made me eager to push myself to notice more slowly. She changed the way I look at what it means to present a single image and make it extend past the frame, she makes me want to maximize time. I think she’s the most talented author the world has ever seen and will ever see. I wonder all the time what it was like to be in her head.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

I love my friends who are artists. They give me so much more than I could ever give myself. The isolationist makes nothing new, and the community based artist who’s primary concern isn’t being novel but being truthful makes beautiful work. The biggest thing I mourn after graduating RISD is being entrenched in art with other artists I look up to every single day. The friends I made at school are some of the most complex and brilliant artists and researchers I’ve yet to see. There, I was pushing and being pushed back. I was viscerally jealous of my peers’ ideas because their works were so beautiful and uncompromising. I was permanently entrenched in art and I’ll never be entrenched like that again. It was the greatest gift I’ve ever received, and every artist I meet gives me hope and happiness. I can only hope to end up on a commune with all my peers again someday in the future with unlimited space, time, and resources. But I’m lucky to be able to have done that for a time, even if it was short. And I have a community that continues with me, even though it’s now scattered.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://survivorsartsandwritingcollective.com/ and. https://marencurtis.com/

- Instagram: @maren.curtis.art

Image Credits

All my photos