We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Mallory Casperson a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Mallory thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. So let’s jump to your mission – what’s the backstory behind how you developed the mission that drives your brand?

My mother was diagnosed with a brain tumor during my last year in undergrad. About a year before her diagnosis, a musical artist performed near where I grew up. He had a brain tumor and sang music about cherishing life and the people we love. A few months into my mother’s treatment experience, I desperately wanted to talk with this musician. I’m not sure what I was looking for but wanted to understand something better about how he was thriving with this dark and scary thing happening in his life (and literally in his head). My mom suggested that I reach out to him, that I could “tell him my story.” It was the first time that I thought about my experience as being valid alongside my mom’s. We were going through this big thing as a family and also as individual people, each with our own part to play, each with our own baggage and role to carry, and each with our own emotions and strengths. Shortly after my mom died, I was diagnosed with cancer for the first time, and a few years after that I couldn’t figure out how to fit my new square life into its old round hole. I couldn’t go back to being the person I was before my mom died and before I had cancer, but I remembered that my story was as valid as anyone else’s. My story involved grief for my mom and grief for my own conceived life path. My story now involved fatigue, anxiety, and worry about the future unlike what I’d experienced before cancer entered my life. So, when my graduate advisor told me that I should take out the mentions of anxiety and fatigue in an appeal letter I wrote to request graduate school accommodations, “because they made me look weak,” I knew that something was wrong. This was not the path for me anymore. I needed to offer myself more compassion and space for healing, and I needed a work environment that did that too. After spending a gap year dreaming and scheming, I founded a nonprofit, Cactus Cancer Society (formerly Lacuna Loft) to offer psychosocial supportive programs to others facing young adult cancer.

Mallory, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

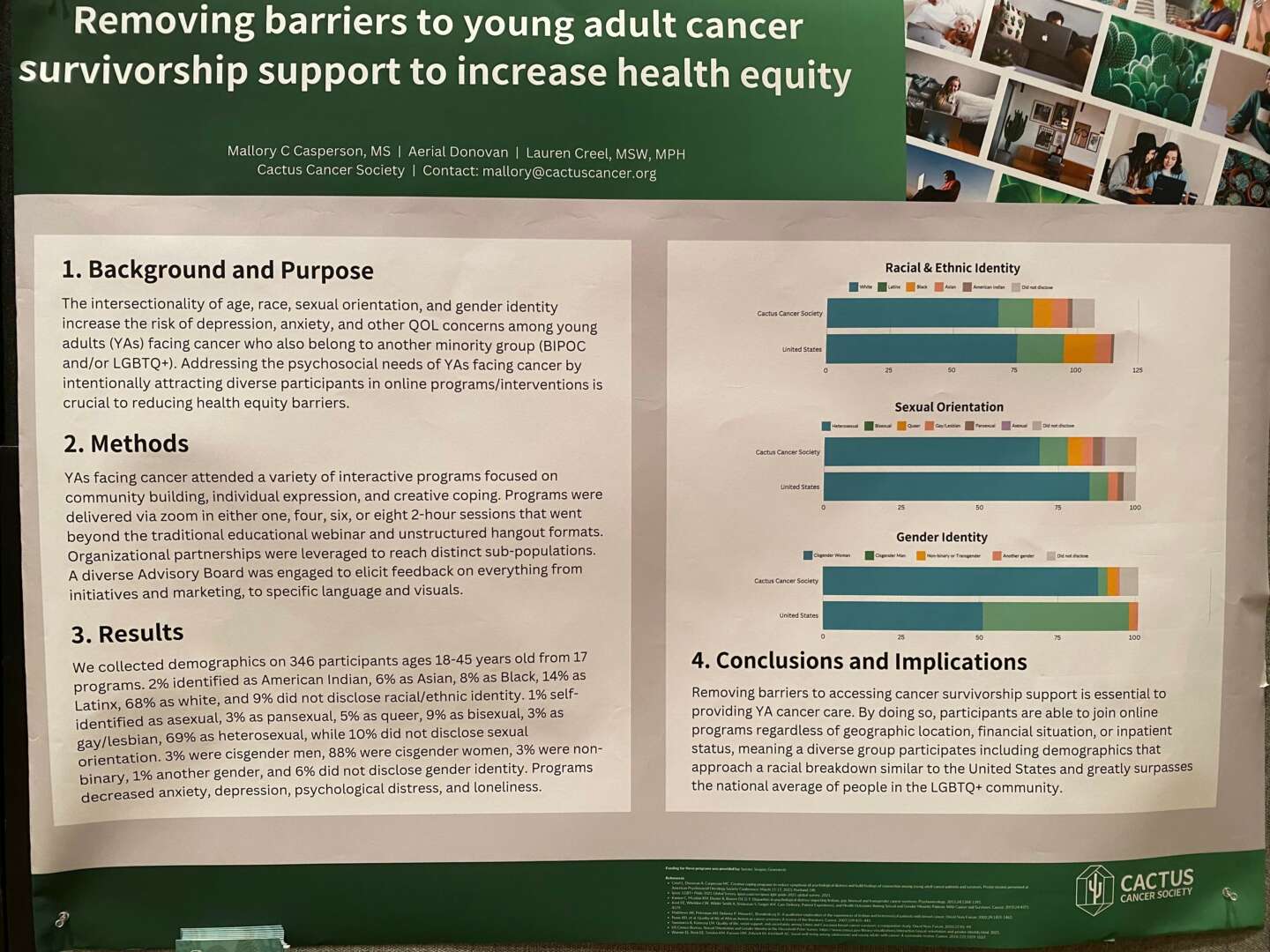

My organization, Cactus Cancer Society, runs online programs for young adults facing cancer that are focused on creative coping, and thriving in the midst of cancer. Since the programs are online, we’ve grown an audience that is diverse in every you can imagine and have removed the significant barriers to receiving psychosocial cancer survivorship care for this age-group. I’m an engineer by training so my organization is also very centered around data and metrics. We specifically consider quality of life burdens such as anxiety, depression, psychological distress, and loneliness and have shown that participating in our online programs reduces these burdens in young adults facing cancer.

Being a caregiver as a young adult and then becoming a young adult cancer survivor was like a death by a thousand paper cuts. All of a sudden, I felt so much of who I was shift. I went from being able to constantly output and work to needing much more rest and self-care boundaries. I went from being courageous and carefree to feeling nervous and anxious. I went from being active and energetic to continually fatigued. I went from feeling excited to get married and have a family to wondering if I’d survive long enough to see either of those futures. I went from feeling connected and in line with my peer group to feeling left behind, out of sync…totally isolated.

Each of these shifts, all on its own, doesn’t seem like much. But add them all together. All of a sudden I was no longer the person I was before. I couldn’t connect with my friends the way I had before. I couldn’t do my job the way I had before. I couldn’t think about my future the way I had before. I felt like my whole world was slipping out from under me, like I was dying from a thousand small uncertainties and changes that were out of my control.

With Cactus Cancer Society, I created exactly what I needed: a connection to young adult cancer survivors who could validate one another’s concerns, fuel one another’s passions for life, and support one another through their biggest transformation yet, becoming a survivor. But Cactus Cancer Society has become so much more than that. Cactus Cancer Society is a safe haven, a safe space in the midst of a world where cancer shifts everything and your ‘normal, healthy’ peer group understands very little, where everyday heroes step up for one another in powerful ways, and where their voices combine to create deep and meaningful change.

10 years into this nonprofit adventure, I’ve now gone through cancer twice. I live in California with a wild rescue pup, a young kiddo obsessed with legos, building things, art, and pokemon, and my wonderful spouse. We love being active all together and going on adventures to the beach, hiking trails, or new places. I’m also really nerdy and enjoy RPGs, board games, and sci fi.

Can you tell us about a time you’ve had to pivot?

My nonprofit organization initially launched as a sole proprietorship. The primary revenue model was built around the (at the time) newly fashionable subscription DIY kits that were just coming onto the market, often via lifestyle brands and blogs. I sold “chemo starter kits” with the idea that everything included was exactly what someone needed as they started or went through chemo. Things like cozy socks, a specific kind of toothpaste, puzzle books, gatorade, chapstick, and more were included in the flagship boxes. The company also had monthly craft kits with the premise that someone could sign up for a subscription and have a specific craft or artsy activity box mailed to them each month. I’d found DIY activities to be critically needed during chemo and the aftermath as I wasn’t able to take part in my usual, more active hobbies. I was often bored and turned to crafting and DIY projects to fill my time and to get myself out of my own head.

Honestly, the idea was solid and I’ve seen more than a few companies come onto the scene over the last decade trying out this same business model. The problem that I had? Marketing. If you were in chemo and knew what you needed, you went out and bought those items. If you knew someone in chemo, you didn’t know what they needed and thus didn’t realize the importance of each specific item included in the box. Was this problem solveable? Sure! Was it one that I felt passionate about and excited to solve? Nope! I wanted to offer support and services to young adults facing cancer and loved connecting with them and their stories. Talking to potential funders, it became clear that to be most readily trusted and funded in the oncology (cancer) space, my company needed to be a nonprofit so that’s what we became! All of the programs have grown quite organically over the years as we’ve responded to feedback from participants and other stakeholders and we do not offer chemo starter kits.

Any advice for managing a team?

To me, a lot of mangement is knowing whose voice in the most important in the room, and finding that voice if it’s not already included. It’s knowing when to speak up and when to take a back seat. When I lead my team, sometimes I hold the most information. Sometimes I have all of the tiny details I need, as well as all of the big picture, pie in the sky pieces necessary to be the final decision maker, even if a team member disagrees with me. Often though, I don’t. In those times, I can help make suggestions based on the higher level, top-down piece of the equation I might hold, but I need to recognize that it’s actually one of my colleagues who needs to make the final decision. Perhaps we need a new donor management system and the employee who will be using it most frequently, helping to integrate it with all of the other operational systems that we use, needs to be the one most bought-in to the choice. Perhaps we need to re-think how we run programs without burning out the team and running through our budget. Perhaps we had a situation arise in a program and we need to seek out the advice of someone with a different lived experience than anyone on my team can provide. If you can’t take a back seat when necessary, you will not succeed.

It’s also crucial to embrace other’s abilities and gifts. The first person I hired at Cactus Cancer Society, who has become my co-founder, Aerial Donovan, was a new-friend who turned into a committed volunteer, then into a board member, and finally into a hired, full-time staff member. We quickly became the best of friends. She is so much more at ease in front of our program participants than in front of funders and professionals in the field while I am the total opposite. She connects whole-heartedly with people, bringing friends quickly into her sphere of influence and adopting them as family while I tag along, benefitting from the wonderful people she attracts. Every once in a while, for whatever reason, we need to switch roles but we will not perform as well as the other one would have. For some time, I tried to figure out how to fix this, how to better coach ourselves, but have learned that it’s actually a good thing. We are each better suited to different pieces of running the organization and that’s ok. We both don’t have to be “best” at everything!

Finally, the last piece of advice I’ll give is that company culture matters just as much as the work you do. I didn’t realize when I started my company how much company culture would come to drive EVERYTHING. The way my employees are treated influences how they treat one another, how they treat our program participants, and then how our program participants treat one another. It drives the expectations for conduct and safe-space that program participants have when they join our programs and then, in turn, helps facilitate that kindness and safe-space we continually strive for. My company has created a culture where open communication is vital. If someone doesn’t understand the motivations behind a decision, they ask, without fear of repercussion or stifling. If someone messes up, we repair as soon as we can. Whether we came to meeting in a bad mood and then took it out on a colleague, whether we made a bad assumption and acted without best intentions, or anything else, we do our best to own up to mistakes and to publicly apologize. We work as colleagues but are also friends, so we have guidelines that drive how we communicate with one another, defining each person’s role in the communication (are we talking as friends or as co-workers, besties or boss to direct report, etc.). We use the phrase, what I’m hearing is…, a lot to prevent miscommunication, we ask for consensus whenever possible, and we work as hard as we can to prevent mistakes from happening again rather than focusing on the mistake itself. Now, I will be the first to admit that I, and my teammates, mess up sometimes, but we always come together as a team in the end.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://cactuscancer.org/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/cactuscancer/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CactusCancer/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mallorycasperson/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/cactuscancersoc

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@cactuscancer

- Other: personal instagram: https://www.instagram.com/malo2/