We recently connected with Mahsa Merci and have shared our conversation below.

Mahsa, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

One of the most formative projects in my career was my first solo exhibition, Hot Blossoms, presented in Iran in 2019. Growing up in a context where personal and social identities are continually negotiated, my early work developed through a visual language shaped by ambiguity, metaphor, and unresolved questions. Painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, and installation became the frameworks through which I examined those questions—both within myself and within the society that surrounded me.

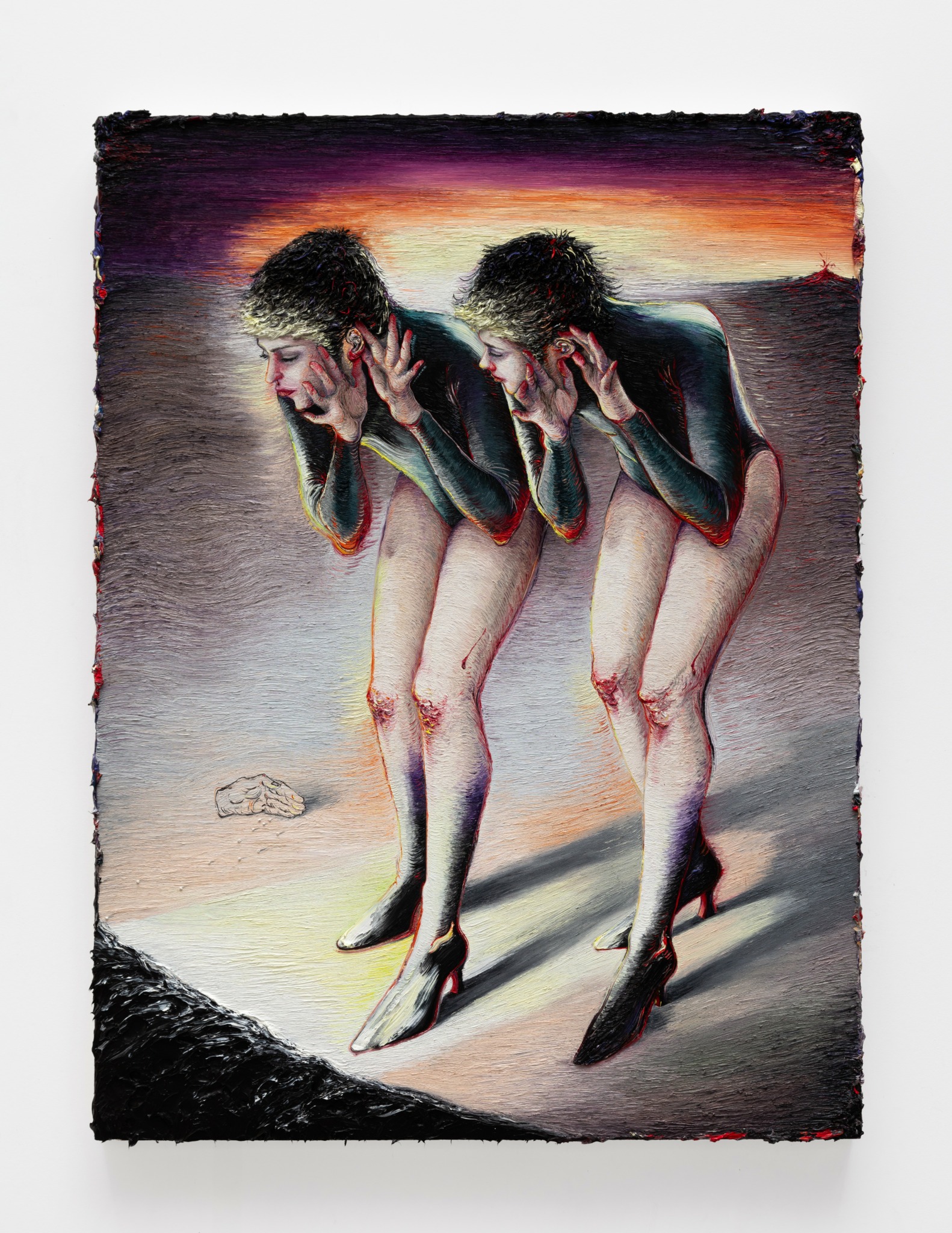

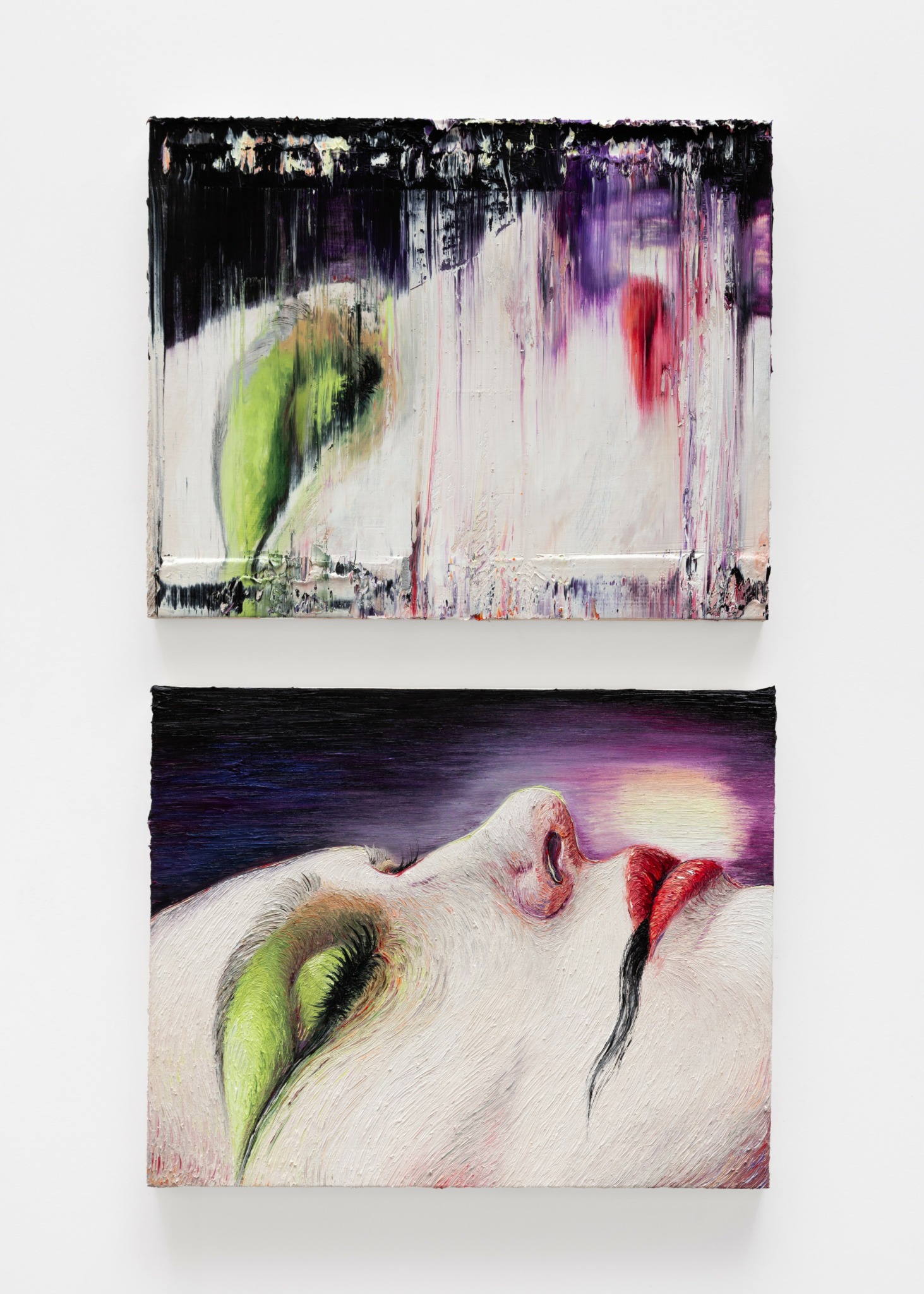

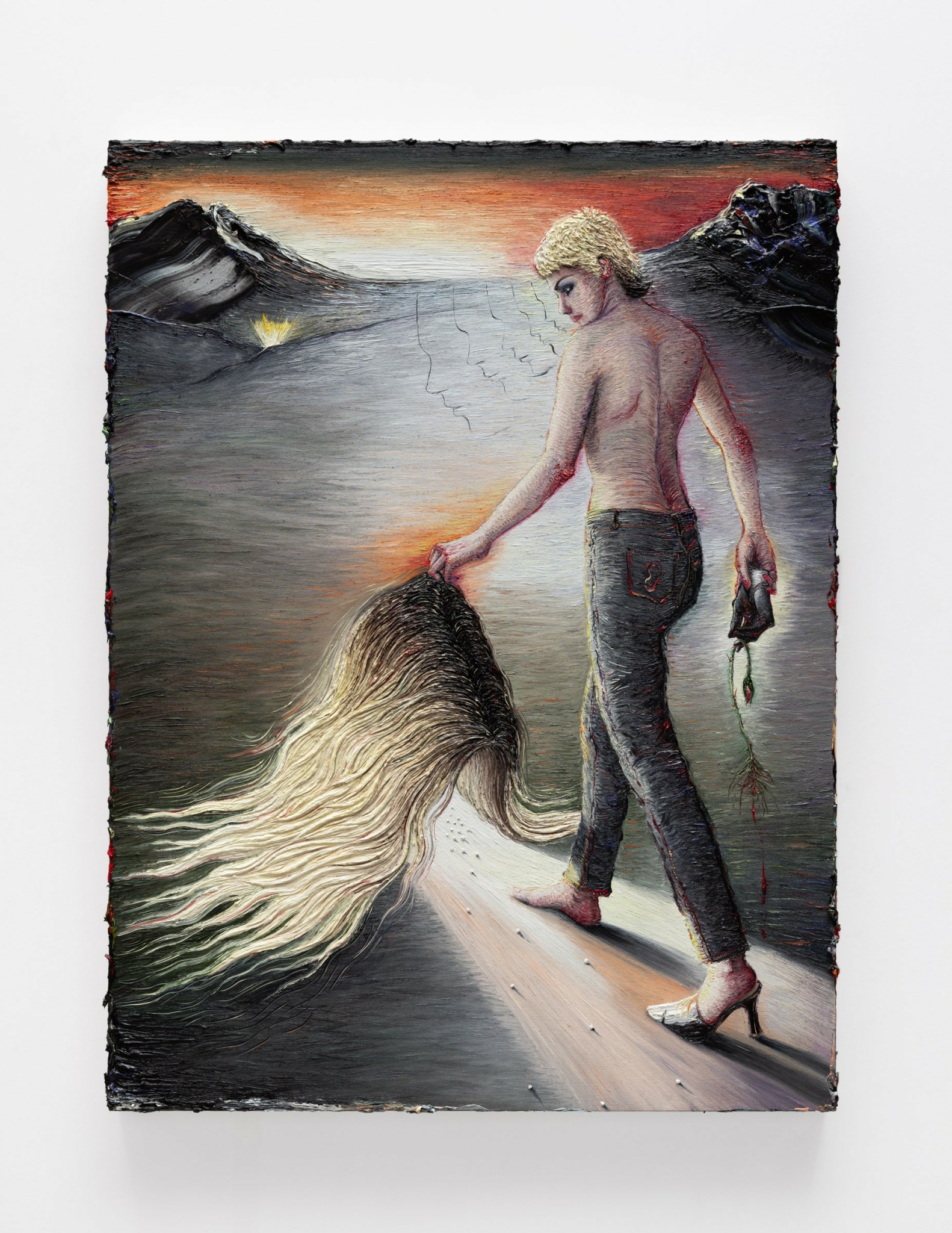

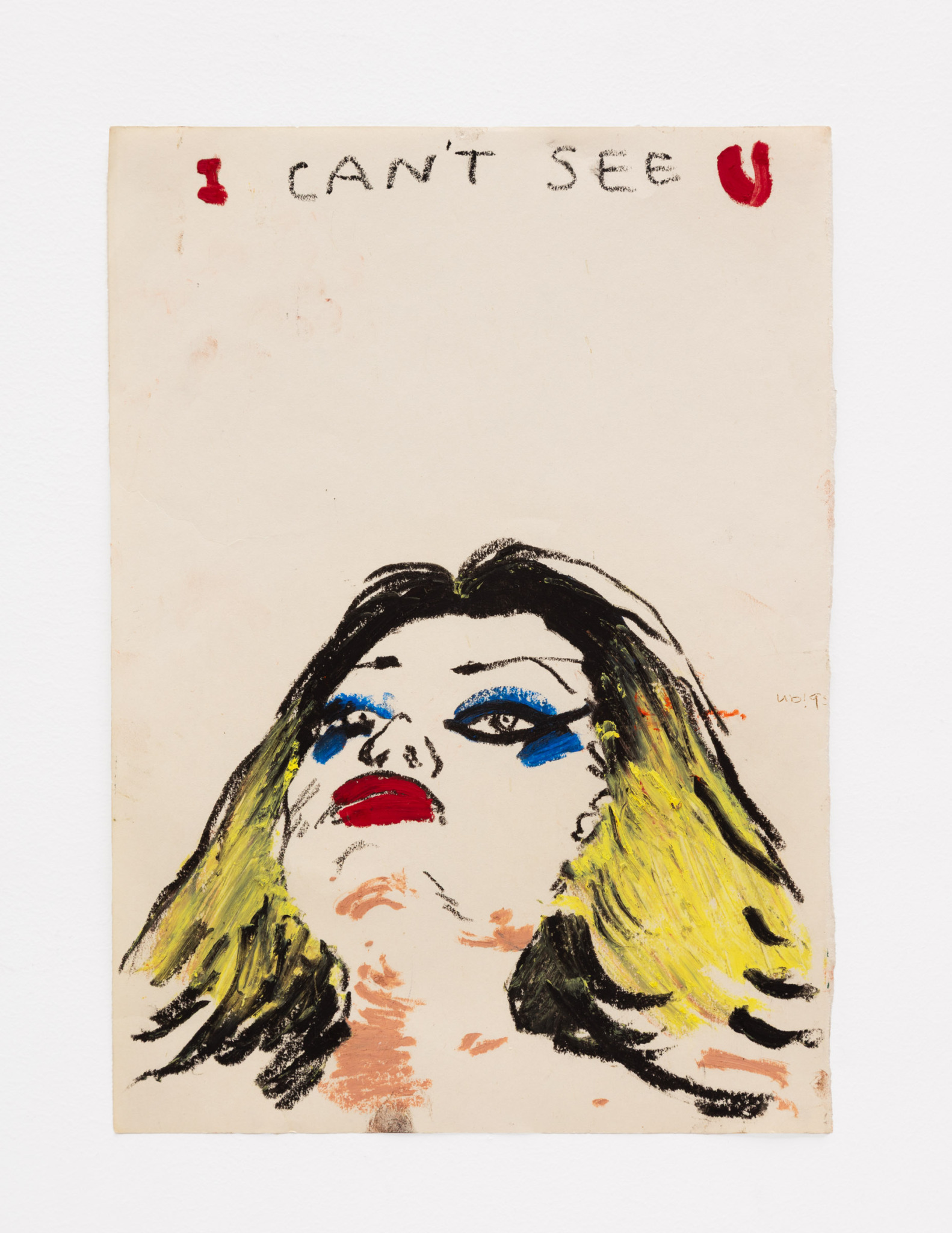

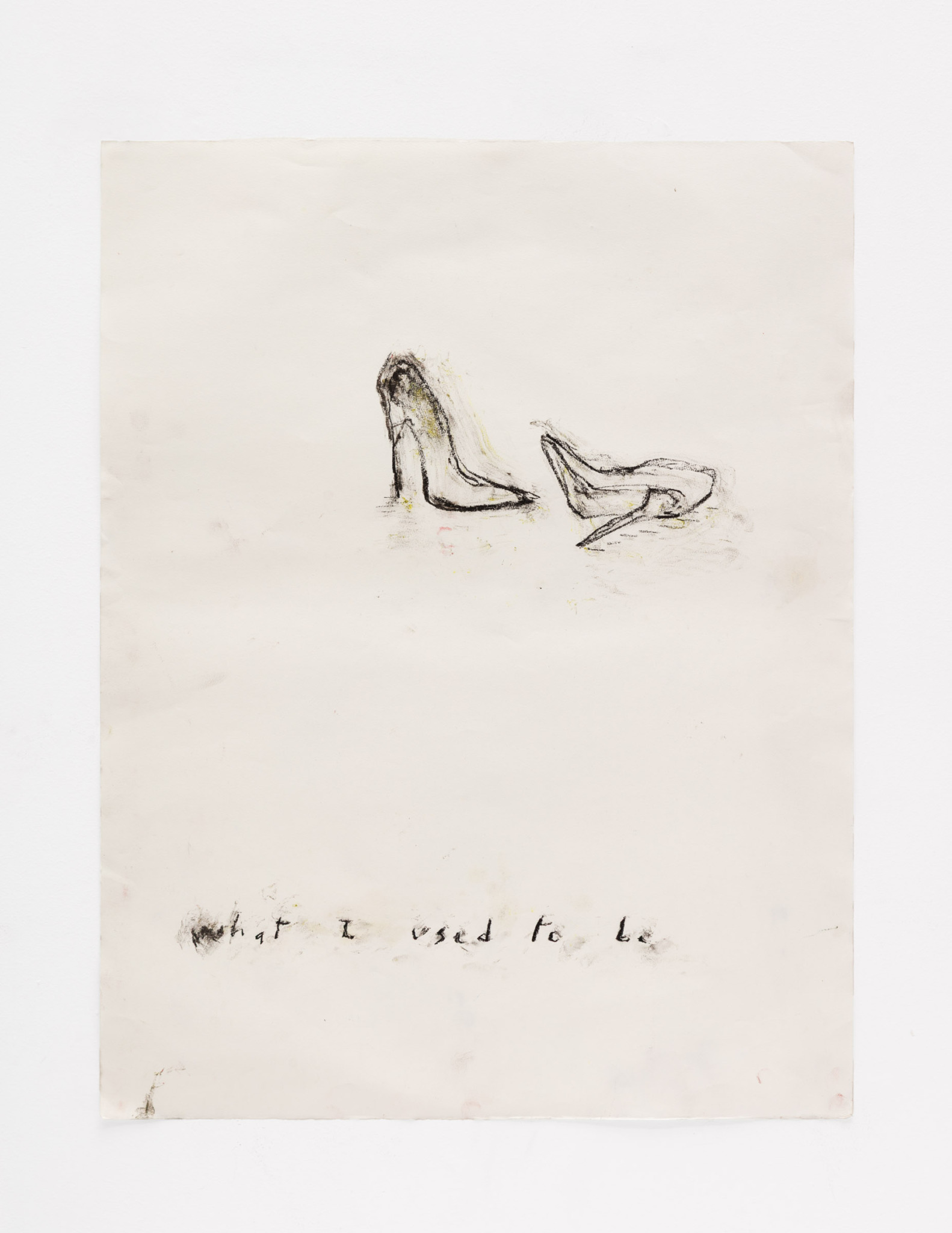

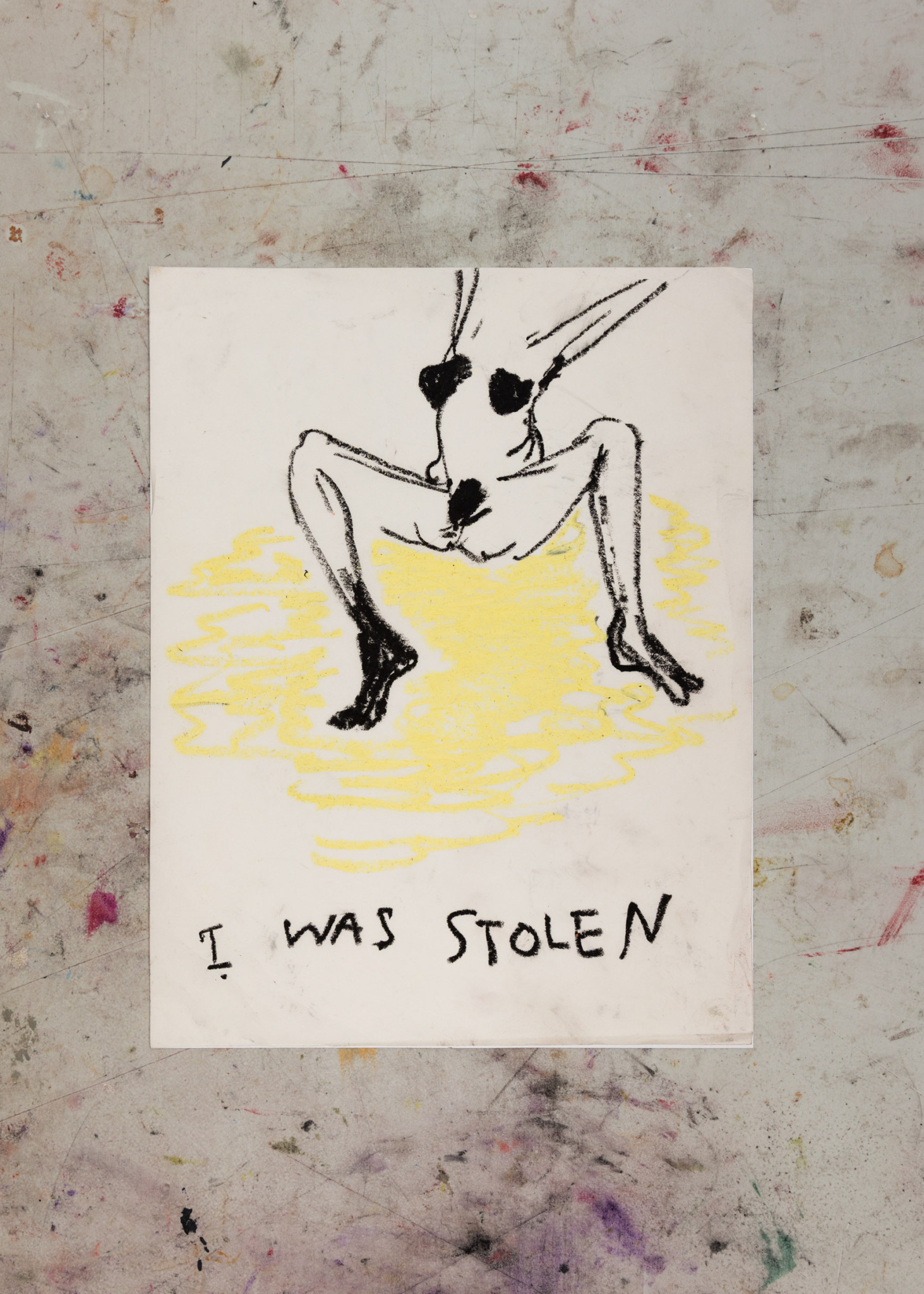

For years, my practice evolved through symbolic forms and fragmented bodies: fingers, hair, eyelashes, high heels, and portraits. These recurring motifs carried the emotional and psychological weight of queerness without naming it directly. They allowed me to articulate states of tension, desire, and constraint while navigating the limitations of the environment in which I was working.

Hot Blossoms was especially significant because it brought those ideas into a full, cohesive exhibition for the first time. The show centred on the experiences, visibility, and emotional geographies of queer Iranians—expressed through abstraction, metaphor, and material choices rather than explicit terminology. Interestingly, most of the audience understood the underlying narrative without any direct reference to “queer” or “LGBTQ+” in the statements or public framing of the exhibition. Despite the constraints, the gallery owner supported the work fully and recognized its political and cultural relevance. He later told me that this was the first exhibition since the Islamic Revolution,more than forty years earlier, that addressed queer subjectivity, even indirectly. The opening was exceptionally well attended and extended an hour beyond its scheduled time.

Mahsa, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

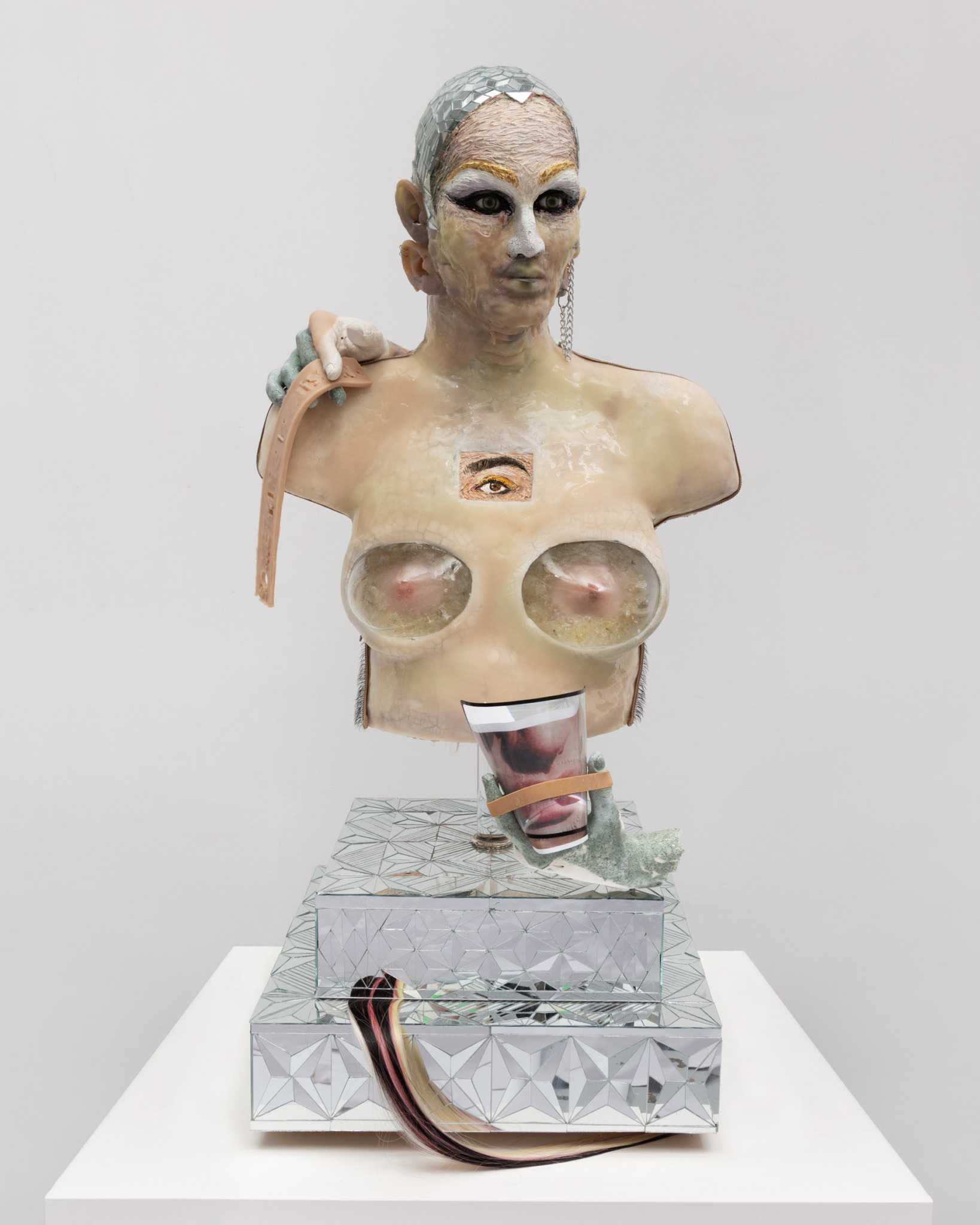

I am a multidisciplinary Iranian artist based in Toronto, working across painting, drawing, sculpture, and installation. At the center of my practice is an investigation into identity—particularly queer identity—and the psychological structures that shape it. My work examines the ongoing dialogue between the conscious and unconscious self, tracing how fear, memory, trauma, and inherited cultural frameworks inform the ways a queer person learns to understand, conceal, and eventually embrace their identity. Growing up in Iran, I developed a visual language grounded in metaphor, fragmentation, and emotional subtlety. These foundations continue to guide my practice as I explore how sociopolitical forces, tradition, and personal history intersect with the most intimate processes of self-recognition.

After immigrating to Canada, my focus expanded toward both Iranian and non-Iranian queer communities. What struck me most was how similar many of the core emotional experiences were—particularly the struggles within families, the unspoken fears, the silences, and the shared forms of trauma. Even in a place like Canada, where many people are open-minded, prejudice continues to exist in more concealed or systemic ways. This led me to think more deeply about the global roots of bias and how it circulates across cultures, shaping queer lives regardless of geography.

I completed my MFA at the University of Manitoba during the pandemic, a period that offered me the rare opportunity to work intensely in the studio. During this time, I created a series of life size portrait paintings of people within my queer community. Built with dense, sculptural oil textures, these works were almost three-dimensional in form. Their scale invited viewers to approach them closely, creating an intimate physical encounter that acted as a metaphor for bridging the emotional and social distance between queer and non-queer communities. In these portraits, I represented each person with absolute fidelity, their appearance, clothing, accessories, partners, and personal belongings. In this sense, the series functioned as a form of documentation through painting.

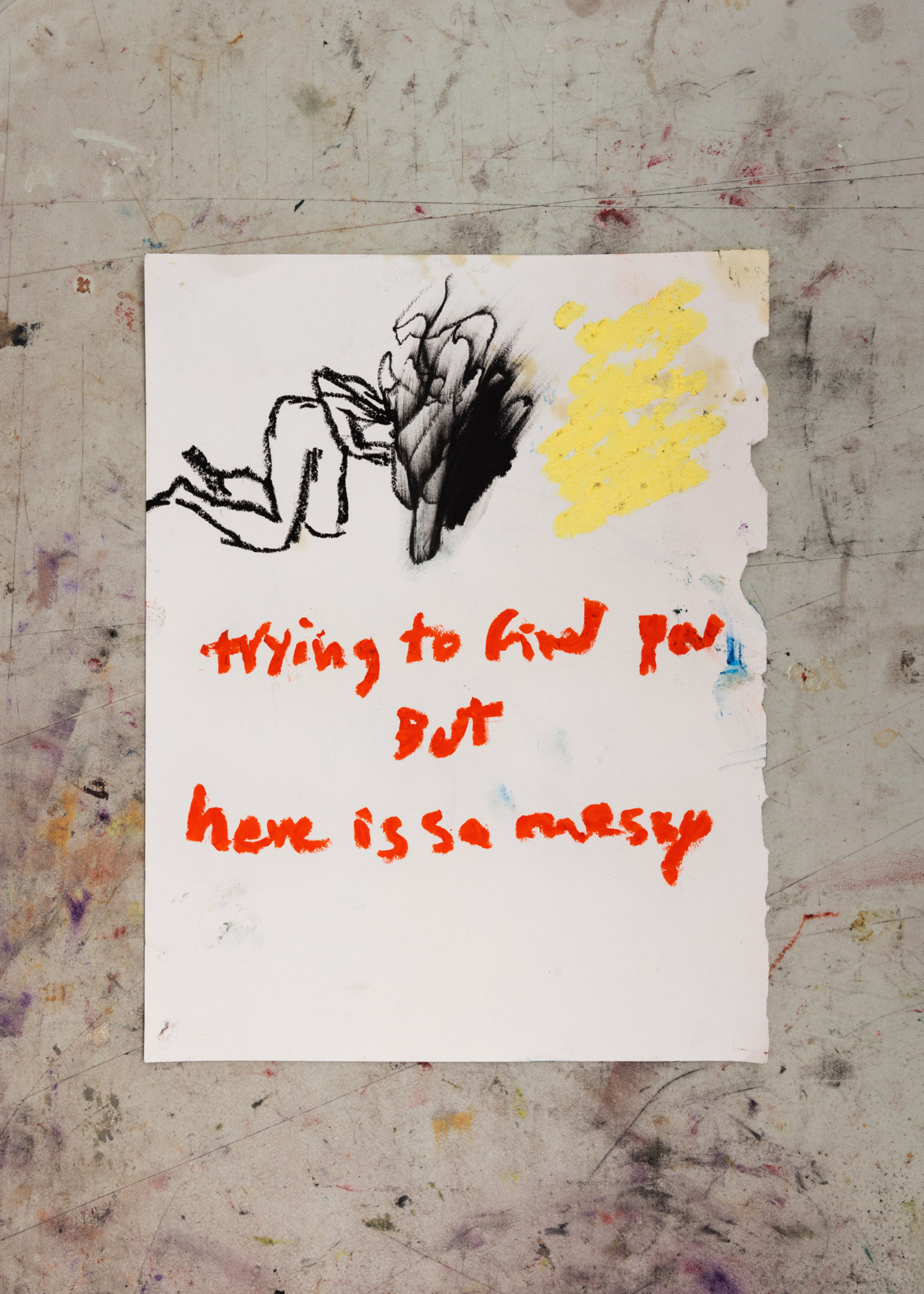

After graduating and moving to Toronto, I found myself re-evaluating my practice. I realized that many of the portraits I had been making were, in some way, indirect self-portraits. Yet I felt absent from the work itself. Slowly, I understood that painting others had been a way of building the courage to eventually paint myself, using their stories as mirrors before turning the mirror inward. My current body of work investigates the journey of self-recognition and acceptance: the boundary between the conscious and unconscious self, the fragmentation of identity, and the emotional landscape of becoming. Light, shadow, doubling, and layered forms appear throughout my recent work as metaphors for questioning, self-awareness, repression, and eventual clarity.

I have exhibited internationally in New York, Toronto, Dubai, Switzerland, Denmark, Germany, Belgium, Hong Kong, and Iran, and my work has been featured in numerous magazines, interviews, and curatorial texts. I have participated in residencies such as Wolf Hill Arts in New York and am currently developing new sculptural and installation-based projects. A defining aspect of my practice is its refusal to separate aesthetics from lived experience; my work is visually bold yet deeply psychological, often merging beauty with tension or unease to reveal the complexities of finding the self.

One of the achievements I value most is my first solo exhibition in Iran, which became the first queer-centered exhibition to take place after the Islamic Revolution. I am also proud of my recent solo exhibition in New York, presented through the Wolf Hill Arts residency, which led to the publication of Wet Light in Midnight. Wolf Hill, with the generous support of Jonathan Travis and Ethan Rafii, played a significant and truly meaningful role in this chapter of my practice, and I am deeply grateful for their support and for the opportunities they created for both the exhibition and the book. Featuring texts by Noor Ale and Sasa Bogojev, two writers and curators I deeply admire, the book stands as one of the most important documents of my artistic journey. Another significant moment for me was having a work composed of dozens of small painted eyes—each based on the gaze of Iranian queer individuals—featured in an exhibition at the HEART Museum in Denmark.

Yet what I value most is the continuity of my studio practice: the daily rhythm of creating, questioning, and searching. It is in those quiet hours that I understand myself—and lose myself—most fully. This inner exploration is what gives my work its depth and purpose.

Ultimately, the defining quality of my practice is its hybridity: a blend of personal history, political context, and material experimentation. My art is both intimate and collective—rooted in lived experience yet connected to larger conversations about identity, queerness, fear, trauma, and psychological truth. Whether encountered in a gallery, a publication, or an installation, my hope is that the work offers viewers a space for reflection and self-recognition.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

One of the clearest expressions of resilience in my journey emerged during the period when my work was shifting between two very different contexts: Iran and Canada. While still living in Iran, I was often told that the subjects I was drawn to would never be allowed to appear publicly. Instead of abandoning those ideas or reshaping myself to fit the environment, I developed new strategies unconsiously, symbolic, metaphorical, and indirect visual languages that allowed me to explore the same realities through layered forms. That period taught me how to remain committed to the core of my practice even when external conditions were limiting.

After immigrating to Canada, an entirely different challenge appeared. Suddenly I had full artistic freedom, yet I struggled to connect with what I was producing. After grduation, for almost two years, I didn’t exhibit. At the same time, the Woman, Life, Freedom movement was unfolding in Iran, carrying its own emotional weight. It was a demanding period: my studio practice felt uncertain, opportunities were paused, and the situation in my home country created a heavy sense of distance and concern.

Despite all of this, I continued going to the studio every day. Even when I wasn’t sure where the work was headed, I knew that stepping away wasn’t an option. Over time, by staying present and working consistently, my practice shifted again, away from overly conscious decisions and toward a more intuitive, unconscious space that felt more authentic to me. That transition eventually opened the way to new exhibitions, new projects, and a renewed clarity in my work.

For me, resilience is the quiet discipline of returning to the studio, trusting the process even when the path is unclear, and allowing the work to evolve with honesty. It exists not only in my routine, but within the conceptual framework of my practice itself.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

One of the most rewarding aspects of being an artist, for me, is the amount of time I spend alone. The studio becomes a space where I am in constant dialogue with my own thoughts, questions, fears, and the deeper layers of my subconscious. So much of an artist’s life is built on solitude—long, quiet hours in which you confront yourself honestly and allow ideas to unfold without expectation. Many of the questions that emerge in that space have no fixed answers, and the answers that do surface often evolve over time. That ongoing process of self-discovery is, for me, one of the most compelling parts of being an artist.

What makes this solitude even more meaningful is the moment when something created within it becomes a bridge to someone else. When a viewer connects with a work, recognizes themselves in it, or feels something they haven’t been able to articulate, a kind of communication occurs that goes beyond language. It is a deeply human and intimate exchange. Knowing that something formed in silence can reach another person on a visual, emotional, and instinctive level is profoundly rewarding. It reminds me why I make art in the first place.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://Mahsamerci.com

- Instagram: @mahsa.merci

- Facebook: Mahsa Merci

- Linkedin: Mahsa Merci

- Twitter: Mahsa Merci

Image Credits

All paintings, sculptures and drawings (with the exception of the large hand image) are credited to LF Documentation.