We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Lynne Hugo. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Lynne below.

Alright, Lynne thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. We’d love to hear about a project that you’ve worked on that’s meant a lot to you.

When I was a new teenager with caring but clueless parents, I used to ride my bike to crazy places on Connecticut’s hilly back roads. Certain natives, especially older teen boys reckless with their shiny licenses, considered those narrow roads their personal racetracks, small wildlife be damned. (I was positive they had cheated on their driver’s tests.) It would upset me so much to come upon a small animal that had been killed that I felt compelled to dismount, to find the fallen branches I’d need to gently move the little body to the woods that edged the road. There, I’d make a soft bed in the undergrowth then cover the animal carefully with leaves and other vegetation, saying how sorry I was and nothing else would hurt it now. I cried often back then.

Now, my family all think I’m a ridiculously conservative driver. It’s probably true. I’ve never said how the habit got started. No, I don’t stop my car in the middle of a road to move an animal’s body, but I still silently mouth how sorry I am when I see an animal that’s been killed, and I’ll happily block traffic to let a live one cross safely. I don’t want animals hurt or suffering, it’s really that simple. If you’ve read my blog or my only nonfiction book (Where The Trail Grows Faint: A Year In the Life Of A Therapy Dog Team), you know how I am about my dogs, always rescues. I’ve always had a great interest in the human/animal connection, the meaningful bond between species and the healing power of that love.

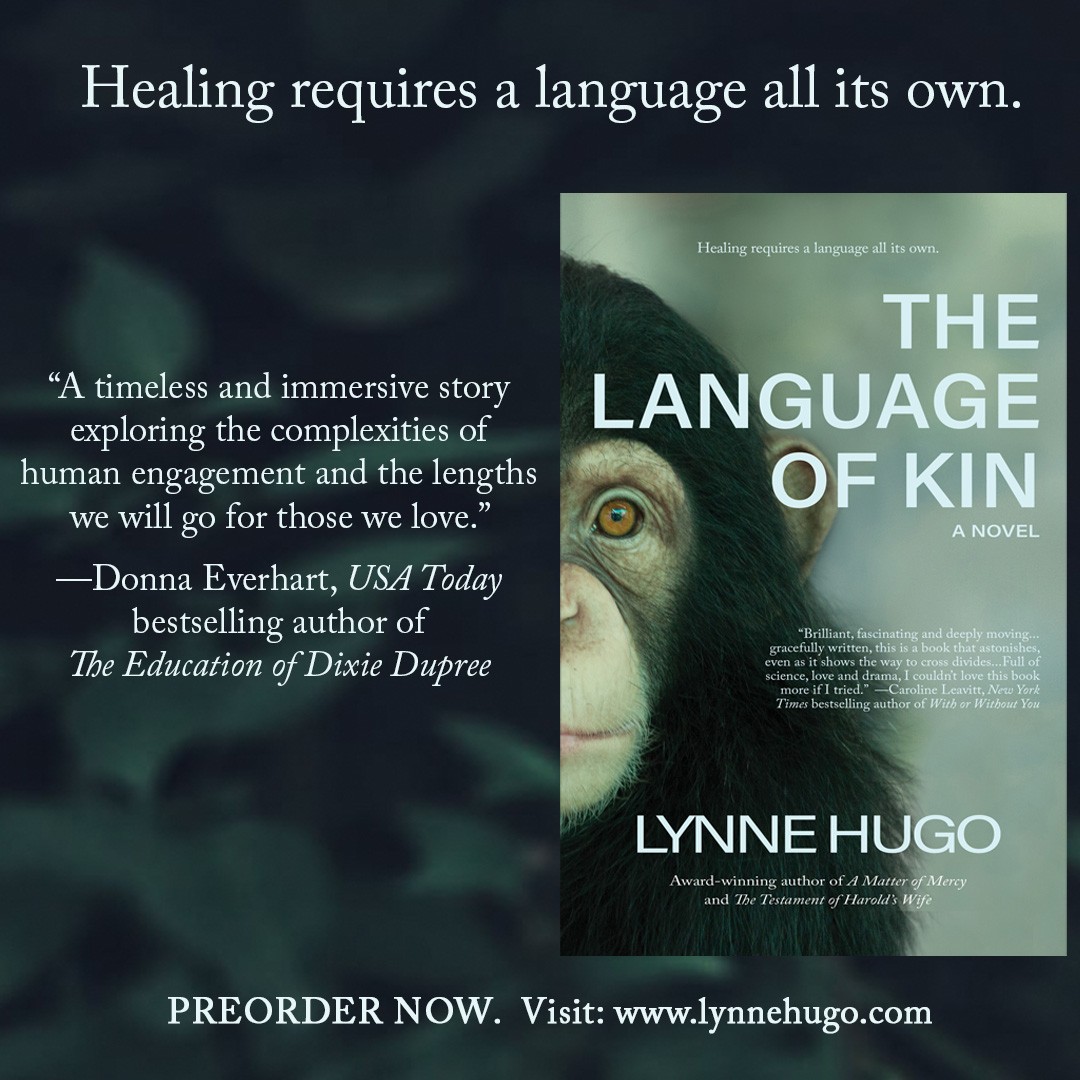

But now, I also want to understand and respect the bonds other animals have within their own species that we humans often seem to disregard. This led me to think more deeply about communication in general, verbal and non-verbal. That, of course, brought me to sign language, too. I had a lot to learn. These were the questions that led me to write The Language of Kin. I wanted to create a dramatic story that would, through characters and action, show how we all struggle to communicate in different ways—how brilliantly we devise ways to succeed, how dismally we sometimes fail.

First, though, writing my latest novel, THE LANGUAGE OF KIN, meant spending time mentally and emotionally in the world of chimpanzees, learning how they live in the wild and in captivity, what they need, how they communicate with us and each other. It meant facing what many endured as laboratory test subjects and what has followed legislation in the United States to stop the medical testing on chimps. Captured, often as nursing babies, drugged, flown here, isolated in cramped, barren cages, subjected to painful experiments, often expressing their distress in self-harming ways: lab chimps spent years suffering. Legislation contained within the endangered species act put a halt to it—and left the labs scrambling with the question of what to do with the now traumatized and scarred chimps they’d experimented on for years.

And then there are zoo chimps. I have always been personally bothered by seeing them—most especially the primates, with whom we share over 98% of the same DNA–in cages in zoos. But I am also aware that conservation of species is a role that zoos increasingly play and that zookeepers focus intently on the well-being of the animals. Several primatologists were incredibly generous with research help, sharing their knowledge and resources, educating me. Relentless climate change and deforestation are enormous concerns with regard to wildlife habitat and there are those who credibly argue that the only hope for the survival of certain species (chimpanzees included) is to breed them in zoos as their natural habitat is being inexorably destroyed. Zoos also can play an important role in educating people about animal needs. But it’s not how they live in the wild. They live in social and family groups, share parenting, learn from each other, fashion and use tools. I understand that there’s not an easy answer, and in THE LANGUAGE OF KIN I did my best to avoid beating a political drum.

My work as a therapist licensed to diagnose and treat mental disorders has given me an abiding interest in human relationships, and I always try to depict them with sensitivity and awareness. Being trained to listen closely has helped me develop a good ear for dialog and I use multiple points of view to reveal character and show how differently people—even people who love each other—sometimes perceive themselves, each other, or a situation. I have also volunteered in a nursing home as an animal-assisted therapist, and this contributed to my interest in interspecies communication, both verbal and signed. Learning to use hand signals with my dog and researching how some chimps have been taught to use American Sign Language also led me to seek consultation about the perceptions and experience of members of the deaf community in order to include the deaf character in this novel.

In the end, I hope my concern and love for animals is clear. Still, although I did a great deal of research and had invaluable consultation with experts, The Language of Kin is very much about the human characters living their human story, the various ways they communicate and fail to communicate, and what they ultimately come to understand and forgive in themselves and each other.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers

I write realistic novels portraying the struggles, failures, humor, and hope of close relationships in today’s complex world. What specifically do I mean by “today’s complex world? Well, in each of my novels one or more of the characters is struggling with some aspect of a contemporary social issue. For example, in THE TESTAMENT OF HAROLD’S WIFE, it was trophy hunting. In THE BOOK OF CAROLSUE, it was immigration via our southern border. And in my latest, THE LANGUAGE OF KIN, which will come out on July 11, 2023, it’s animal welfare (as well as the human-animal connection. What I’m proudest of is how hard I work to avoid being a partisan, but to underpin my stories with solid research, well-hidden in the drama, but keeping it fair and true. Characters are allowed to have strong opinions and stances in my work but there always has to be some credible opposition. I assume my readers are able to think critically and independently–and prefer to!

My first two books were poetry, but I found that I always had a story buried in the poems and that led me into separate short stories until soon characters took over and wanted more and more space and the ten books since have been full-length. I love writing dialog, especially, but the crafted language of poetry was really good training for describing people, emotion, and environments. Another factor that I’m sure helped my writing is that I’m also a licensed clinical therapist. Years of close listening to people and watching their body language and faces as they discuss what is bringing them pain or relief or joy has fine tuned my ear to how people express themselves in their life-changing experiences.

My aim is to write novels with which readers can identify, that they will want to think about, share and discuss because they genuinely enjoyed it.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

I think the most rewarding aspect of being a novelist is that all experiences, good and bad, are grist for the mill. Everything I see, hear, read, watch, etc., is something to be closely observed, examined, and learned from as an aspect or example of the human experience. I can always ask myself–is this different in some way? How can I use this to deepen my understanding? What can I learn from this and use in my fiction? Not ever, of course, to tell or show someone else’s experience–which I would consider unethical–but perhaps to depict nuance of emotion, or color, or scenery or action in a new way? Can I describe how X’s eyes change when she is surprised, the way Y person just did it in real life? What does that tone of voice remind me of? Is there a metaphor that captures that?

I love that nothing I experience needs to be chalked up as as waste. I can mark it “save” in my memory files and sometime, in some chapter in some novel, I’ll use it.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

Value them! I think this would primarily start with supporting and teaching the arts throughout elementary, middle school and high school. Ideally, art and music wouldn’t be electives–kids could alternate music and art, and all have the experience of exhibiting and performing. When I was in high school I was in the choir for which you had to audition and I still remember the music we performed, how much I learned, and am grateful for the depth and richness it has added to my life, although I was never better than an average singer. Even my excellent public school never required art or music after 8th grade, and now I’m sorry I know so little about art because I never took it in high school (or college) even though my school had a robust program with varied options, as it did with music–several bands and ensembles as well as a no-audition chorus.

For a number of years I served as an Artist in Residence, teaching creative writing to kids in Ohio schools by spending several weeks each in residencies in various towns. The school would apply to the Ohio Arts Council for a grant, and I would be paid through the OAC to go. Sometimes I’d be able to arrange for them to pay a second artist to come for three days of a three or four week residency to help me stage a public performance by the kids, to read their own work. We were able to get it on public TV several times, too. Those kids learned so much, grew so much.

There were comparable artists in a number of artistic disciplines, and schools would apply for the discipline they wanted and could choose the creative they wanted to come. Teachers loved the program, kids loved it, and the artists exposed many people to their work and discipline because they also did a reading, or perhaps an exhibition in the residency town. It was a truly great program that no longer exists. The legislature cut the funding as they also cut funding for public universities, and for many other programs.

I believe that if we did a better job of elevating the arts in our educational system, giving them equal status with our academic programs, that our society would support the arts more by going to museums and galleries and supporting orchestras and opera and dance companies, etc. Maybe some would read more, watch less television if they had once thought of themselves as creative writers or had kept up some of the habits of observation. But, I think people would be less willing to reduce or eliminate agencies like The National Endowment for the Arts and state Arts Councils wouldn’t be chronically short on funds.

I know it’s hard, but people do pay something for what they care about–what they feed their children’s bodies, for example. I think we should care as much about what we feed their minds because it will nourish their entire lives.

Contact Info:

- Website: http://www.LynneHugo.com

- Instagram: LynneHugoAuthor

- Facebook: Lynne Hugo Reader’s Page

- Twitter: @LynneHugo

Image Credits

Author photo: Alan deCourcy